Sir Norman Graham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

So Proud to Come from Govan

Annual Review 2017 So Proud to Come from Govan Annual Review to 31 March 2017 Annual Review 2017 AILEEN McGOWAN was born and brought up in Govan, attending St Saviour’s Primary and St Gerard’s Secondary schools. She started work in 1967 in ‘Fairfields’, first as a Clerical Assistant in the Pipe Shop before promotion to the Buying department and the post of Progress Chaser based in the main office building on Govan Rd. Finding herself the only young person in the department, she yearned to be among colleagues of a similar age and left in 1969 for Glasgow City Council where she ultimately from the chair became a Housing Officer at Mosspark Rent Office. Aileen McGowan, the newly elected Chair of Govan Workspace From 1975 Aileen took a 5-year career break to start a family after IT GIVES me great pleasure to present turned out to be a great community which she attended Cardonald our Annual Review in what has been event which drew people of all ages. College and completed three another busy and successful year for The highlight for me was seeing the Highers. The next move was to Govan Workspace. But before doing GYIP kids (of Govan Youth Information Paisley University and graduation in that, my first task must be to thank the Project) starring for the day as Sir Alex’s 1985 with BA (Hons). board for electing me as their Chair. It bodyguards, complete in Viking uniforms. is a tremendous honour to be asked to Sir Alex himself was a true gentleman and Her chosen profession from take on that role in such a successful and left these young people and their families that point onwards was in Careers, worthwhile enterprise. -

Govan Old Parish Church" with These Words

THE BAPTISTRY The Revd Tom Davidson Kelly, MA BD (Minister of Govan Old) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * From the birth of the Friends (... of Govan Old ...) in 1990 the fully restored Baptistry has been seen as the kernel of our Ministry to Visitors. As we were plan- ning how best to use the limited space in the Baptistry as an exhibition area, legacies and donations to restore the Shrigley & Hunt stained glass windows began to come in. These windows are part of the window scheme in which Dr John Macleod was in- volved at every stage, apart from the installation only months after his death in August 1898. These 7 windows encourage reflection on the signifance of the Incarnation and the meaning of Christian Baptism. The first act of vandalism to the Baptistry was recorded in the Kirk Session minute for 5th June 1900: Mr Black [an Elder] intimated that the damaged windows in the Baptistry had been repaired by the Insurance Company. We optimistically finished "The Stained Glass Windows of Govan Old Parish Church" with these words: By 1990 the windows have become dirty and damaged. Hopefully, soon it will be possible to begin a programme of conservation, and where (as in the Baptistry) too much of the original glass has been lost, restoration. Stained Glass Design Partnership had submitted a report on the Baptistry windows as early as 1990. By the time the First Annual Report was distributed in March 1991, sufficient funds were available to conserve the 5 more complete windows. Local show- men, and in particular the Stringfellow family, helped mount the First Govan Easter Carnival. -

The Battle of Linwood Bridge

RLHF Journal Vol.6 (1994) 6. The Sculptured Stones of Govan and Renfrewshire Irene Hughson In April 1994 members of the Pictish Arts Society travelled to Paisley to join members of Renfrewshire Local History Forum in a day devoted to the study of some examples of what is now called the Govan School of sculpture. Compared with the magnificent craftsmanship and original symbolism of the true Pictish stones what we have in Govan and the surrounding area is late, derivative and much of it inferior in execution. The stones of the Govan School come towards the end of a long tradition in sculpture rather than at the beginning. They are nevertheless very intriguing, and well worth a visit. Though some of them may lack the delicacy and intricacy of earlier work, the interlace patterns are simple and bold. The animal carving is vigorous and attractively “chunky." In Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson's classic work (now, of course, re-issued by a P.A.S. member) the stones were simply designated as Class 3. (1903 and 1993) There are, however, stylistic similarities within a fairly well defined geographical area which justifies the use of the term ‘school.' Historically they are rather puzzling. There is a large number of stones - more than 50 altogether - with a concentration of over 30 at a single site, namely Govan Old Parish Church which is absolutely and totally absent from historical records. Probably because of that, the collection has received rather less scholarly attention than other groups of stones, and has been virtually ignored by cultural tourists who make pilgrimages to Aberlemno, Meigle and St. -

The-Sacredness-Of-Natural-Sites-And-Their

230 The ‘sacredness’ of natural sites and their recovery: Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair McIntosh Science and the sacred: with which science can, and even a necessary dichotomy? should, meaningfully engage? It is a pleasing irony that sacred natural In addressing these questions science sites (SNSs), once the preserve of reli- most hold fast to its own sacred value – gion, are now drawing increasing rec- integrity in the pursuit of truth. One ap- ognition from biological scientists (Ver- proach is to say that science and the schuuren et al., 2010). At a basic level sacred cannot connect because the for- this is utilitarian. SNSs frequently com- mer is based on reason while the latter prise rare remaining ecological ‘is- is irrational. But this argument invariably lands’ of biodiversity. But the very exist- overlooks the question of premises. ence of SNSs is also a challenge to sci- Those who level it make the presump- ence. It poses at least two questions. tion that the basis of reality is materialis- Does the reputed ‘sacredness’ of these tic alone. The religious, by contrast, ar- sites have any significance for science gue that the basis of reality, including beyond the mere utility by which they material reality, is fundamentally spiritu- happen to conserve ecosystems? And al. Both can apply impeccable logic is this reputed ‘sacredness’ a feature based on these respective premises < Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) 231 and as such, both are ‘rational’ from cie rule themselves out of court from a within their own terms of reference. scientific perspective. For example, idea that God (as the ‘ground of be- This leads some philosophers of sci- ing’) created the world in six days is ence to the view that science and reli- manifestly preposterous. -

Prayer of the Month • June 2013

Prayer of the Month • June 2013 You are released, resplendent, in the loving mother, the dutiful daughter, the passionate bride and in every sacrificial soul. Inapprehensible we know you, Christ beside us. Intangible, we touch you, Christ within us. With earthly eyes we see ourselves, dust of dust, earth of the earth; fit subject at last for the analyst’s table. But with the eye of faith, we know ourselves all girt about of eternal stuff, our minds capable of Divinity our bodies groaning, waiting for the revealing, our souls redeemed, renewed. Intangible we touch you, Christ within us. George MacLeod 17 June 1895 – 27 June 1991 George MacLeod, founder of the Iona Community, writes poetically and thoughtfully, reaching after images that convey the earthly reality and the spiritual indwelling. With words like ‘resplendent’ and ‘inapprehensible’ MacLeod explores the richness of the English language . The prayer recognises the commitment of individuals to another, that is also a commitment and recognition of God within, with the uniting underlying focus on sacrifice. Born in Glasgow in 1895, George MacLeod was the son of a Scottish businessman, and the grandson of the Rev’d Norman MacLeod, sometime Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. After studying at Oriel College, Oxford, George MacLeod joined the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders in 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, rising to the rank of Captain. The shocking experience of war led him to train for ministry, and he studied at the University of Edinburgh and then Union Theological Seminary in New York City. -

Ght4thed 2003

A Brief History Govan is situated opposite the confluence of the Rivers Clyde and Kelvin. h was once surrounded by fertile lands and woods. The place name of Govan has its roots in Cehic with similar words found in both Gaelic and Welsh (British). Gofan, Gowain, Gwvane, Govaine, Gohan and Goven translate to mean Smith or Land of the Smith. Govan may have been named for its reputation as an area where metal was worked. lndeed the presence of Doomster Hill and the round shaped graveyard of Govan Old Parish Church would suggest that there was a com- munity long before the Romans arrived. The ecclesiastical history of Govan dates back to the early monastery founded by St Constantine around 565 AD. Constantine was a contemporary of Columba and Kentigern. He wayeputed to be a Cornish Kinf, although recent historians prefer lrish or Scottish origins. The date of his Martyrdom was around 596AD. It was not until around 1147 lhal the name of Govan was historically recorded when King David I gave to the church ol Glasgu,'Guven'with its 'marches free and clear forever'. lt was during this period that the church in Govan was made a prebend (an associated church) of Glasgow Cathedral in or around 'l 153. Govan was primarily a fishing and farming community, although by the l6th Century there were extensive coal mine workings in the Craigton and Drumoyne areas. The village grew as new trades and crafts were established such as weaving, silk manufacture, pottery Many Govanites thought that it should have been the and the dyeing of cotton. -

Govan and Linthouse Parish Church Magazine March 2011

Govan and Linthouse Parish Church Magazine March 2011 G and l Mag Mar 11 Sidelines In Hunan province in China, there is a range of mountains, the Tinamen Mountains. To get there you have to go on the ‘Highway to Heaven’ which is a snaking road, coiling itself up the mountain and rising from 200- 1300 feet from base to summit. If you go by bus or car, you have to stop for the last hundred metres or so, and get out and climb 999 steps, the heavenly ladder. If you survive that, and get to the top, there is a modern Buddhist temple, and an eroded cave entrance, where all that is left is this massive, natural arch in the rock. It is so large, that they have occasionally had air displays where the planes fly through the arch and above the heads of the daily visitors. This arch, the locals believe, is the gateway to heaven. Apparently (I have never been) the views at the top are breathtaking, and people feel that they have a heaven’s-eye view on the rest of the world. Wouldn’t it be good if we could have a heaven’s-eye view on our parish, our efforts, the glaring gaps for which we are responsible, the people we hardly notice, the way in which our church world impacts upon the non-church world - if it does at all. What would it look like? Would there be a view of those things we do well? Could we see where we have been negligent or careless? What would be the heaven’s-eye view of our church in its parish context? Our Presbytery, indeed the whole church, is going through another organisational convulsion. -

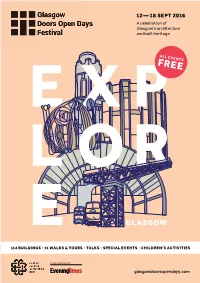

Glasgow’S Architecture and Built Heritage

12 — 18 SEPT 2016 A celebration of Glasgow’s architecture and built heritage ALL EVENTS FREE GLASGOW 114 BUILDINGS • 51 WALKS & TOUrs • TALKS • SPECIAL EVENTS • CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES In association with: glasgowdoorsopendays.com THINGS TO KNOW Details in this brochure were correct at the time of going to print, PHOTOGRAPHY but the programme is subject to change. For updates please check COMPETITION WIN glasgowdoorsopendays.com, sign up to PRIZES! H E our e-bulletin and follow our social media. GlasgowDoorsOpenDays GlasgowDOD GlasgowDoorsOpenDays TIMINGS Check individual listings for opening hours and event times. Send us your photos of AccESS L L O Due to their historic or unique nature, Doors Open Days 2016 we regret that some venues are not fully accessible. Access is indicated in each and win some fantastic listing and in more detail on our website. prizes! FOR THE faMILY Glasgow Doors Open Days is The majority of buildings and events are fun for children and we’ve highlighted back for the 27th year, celebrating key family activities on page 34. We’ve CATEGORIES also put together a dedicated children’s Inspired by Mackintosh | People and Place | Glasgow’s unique architecture programme which will be distributed to Architectural Detail | Cityscape | Behind the Scenes and built heritage! This year Glasgow primary schools in late August. YOU COULD WIN VOLUNTEERS – £250 voucher to spend at Glasgow Architectural Salvage we’re part of the national Festival Doors Open Days is made possible – A year’s subscription to Scots Heritage Magazine -

Proposal # 483473 Name: Kaye Carmichael Tour Name: Carmichael Travel Tour Date: September 2019

Proposal # 483473 Name: Kaye Carmichael Tour Name: Carmichael Travel Tour Date: September 2019 Sept 12 DEPART THE UNITED STATES Depart from Birmingham on United’s flight #3996 to Chicago, leaving at 10:40am and arriving at 12:48pm. Connect to United’s flight #118 to Edinburgh leaving at 6:15pm. Enjoy in-flight entertainment and meal service as you travel to Scotland. Sept 13 EDINBURGH ARRIVAL Arrive at Edinburgh’s airport at 7:50am where you will complete customs and immigration formalities. Your CIE Tours guide will welcome you to Scotland and escort you and your luggage to the coach. Next, set off on a guided panoramic tour of Edinburgh to see some of the city’s magnificent highlights. During your tour, you will travel through the Old Town and, of course, along the Royal Mile. If time permits, you will also see the Palace of Holyroodhouse, St. Giles Cathedral and even the National Museum of Scotland. Transfer to your nearby hotel, check in and enjoy some time for lunch on your own and a free afternoon. In the evening, join your fellow travelers for dinner in the hotel restaurant. DINNER & OVERNIGHT: PRINCIPAL CHARLOTTE SQUARE HOTEL, EDINBURGH Sept 14 EDINBURGH SIGHTSEEING This morning, embark on a guided tour of Edinburgh to see some more of the city’s highlights. You will stop for a guided tour of the imposing Edinburgh Castle, perched high above the city on volcanic rock. Also visit Greyfriars Kirk, which sits just outside the Old City, near the Grassmarket. It is one of the oldest surviving buildings from the 1600s and has an interesting connection to the Reformation. -

Central Govan Action Plan (2006)

CENTRAL GOVAN ACTION PLAN Central Govan Action Plan Client Group Consultant Team Glasgow City Council McInally Associates Greater Govan Social Inclusion Partnership GD Lodge and Partners Govan Housing Association Ann Nevett Landscape Architects Linthouse Housing Association Dougall Baillie Associates Elderpark Housing Association Graham and Sibbald Scottish Enterprise Glasgow RESOLUTION Resolution Greater Govan Community Forum Govan Initiative CENTRAL GOVAN Communities Scotland ACTION PLAN April 2006 Contents 1 Introduction . 1 2 Population and Housing . 3 3 Economic Activity and Employment . 7 4 Retail . 11 5 Heritage and Conservation . 17 6 Townscape . .................................21 7 Transport and Movement ..........................33 8 Landscape. 41 9 Community, Leisure and Recreation . 53 10 Implementation . 59 11 Indicative Layouts and Elevations. ...63 Appendices A Appendix A : List of Vacant Properties B Appendix B : Retail Property Valuation C Appendix C : Public Consultation D Appendix D : Development Plan and Other Planning Policies E Appendix E : Photographic Survey of Existing Shops [September 2005] TABLE OF The Ordnance Survey mapping data included within this publication is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to act as a planning authority. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping data for their CONTENTS own use. CHAPTER 1 : INTRODUCTION 1 Glasgow City Council, in partnership with Scottish Enterprise, THE REMIT Communities Scotland, Greater Govan Social Inclusion Partnership and Govan Initiative (the Client Group), commissioned the The Client Group prepared a remit to define the principle preparation of an Action Plan for Central Govan in December 2004. -

George Macleod's Open-Air Preaching

T George MacLeod’s open-air preaching: Performance and counter-performance Stuart Blythe The Clydebank Press on Friday 15th August 1941 reported: There was a nice little bit of diplomacy that Dr Geo. F. MacLeod, the renowned Scottish preacher, used addressing an open-air meeting in the burgh last Friday. Coaxing his hearers, mostly artisans in the yard, to come closer, he remarked that he did not believe in shouting like most open-air speakers, ‘Not that I cannot do so,’ he added with a smile, and in a much louder voice, ‘but if I can get you all the nearer to me there is no necessity for it.’1 Ron Ferguson writes MacLeod was ‘a born actor and showman who enjoyed an audience’.2 Such language is not always considered appropriate in the description of matters ‘spiritual’. Yet, these qualities and attention to them contributed to MacLeod’s performances as a ‘renowned’ preacher and communicator both in ‘God’s theatre’ of a congregation gathered in worship and as a popular radio and television presenter.3 In turn in this article, I will abjure pejorative connotations and draw on performance theory to introduce and analyse George MacLeod’s open-air preaching as performance and counter-performance. MacLeod’s open-air preaching T George MacLeod’s ministry at Govan Old Parish Church between 1930 and 1938 included regular ‘evangelistic’ or ‘missional’ open-air preaching.4 Such open-air preaching also played a significant role in page 21 key events, including the ‘Week of Friendship’ in October 1934, the climax to a two-year parish mission, and ‘Peace Week’ in 1937. -

A History of Govan to 2011

A History of Govan to 2011 Although the first written mention of the River Clyde (the Clota) was not until the Roman author Tacitus i wrote his „Agricola’ in AD 98, we know from the evidence of Monolithic stones and Neolithic canoes that people were living and working in that area of the Clyde c. 2,500 BC. We also know from recent archaeological digs that people continued to live in Govan through the Bronze and into the Iron Age when a settled, metal-working community lived at Govan around the year 750 BC. ii From that time until the present, people have been residing in the same area which means that Govan is one of the oldest continually inhabited places in the world. The name „Govan‟ is first mentioned in the 12th century Historia Regnum Anglorum as Ouania – a place which lay near the stronghold of the Strathclyde Britons at Dumbarton Rock. There are two versions about the origin of the name: one comes from folk etymology and is based on the Gaelic word „gobha’ meaning a smith or „place for ironworkers‟. iii The other name for Govan is „goban’ which derives from a north British or Old Welsh dialect which translates as „little hill‟. As Govan is relatively flat, the coining of the word might have been used for what was Govan‟s most defining feature then - Doomster Hill, which stood adjacent to the present day Govan Road, Water Row, and the river itself. iv This huge heap of earth was a stepped, two-tiered man-made mound that was 17 feet high, with a diameter of 150 feet at the base and 107 feet at the top.