Post-Race Ideology and the Poetics of Genre in David Mamet's Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

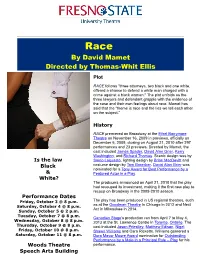

Race by David Mamet Directed by Thomas-Whit Ellis Plot

Race By David Mamet Directed by Thomas-Whit Ellis Plot RACE follows "three attorneys, two black and one white, offered a chance to defend a white man charged with a crime against a black woman." The plot unfolds as the three lawyers and defendant grapple with the evidence of the case and their own feelings about race. Mamet has said that the "theme is race and the lies we tell each other on the subject." History RACE premiered on Broadway at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on November 16, 2009 in previews, officially on December 6, 2009, closing on August 21, 2010 after 297 performances and 23 previews. Directed by Mamet, the cast included James Spader, David Alan Grier, Kerry Washington, and Richard Thomas. Scenic design was by Is the law Santo Loquasto, lighting design by Brian MacDevitt and Black costume design by Tom Broecker. David Alan Grier was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Performance by a & Featured Actor in a Play. White? The producers announced on April 21, 2010 that the play had recouped its investment, making it the first new play to recoup on Broadway in the 2009-2010 season. Performance Dates Friday, October 3 @ 8 p.m. The play has been produced in US regional theatres, such Saturday, October 4 @ 8 p.m. as at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago in 2012 and Next Act in Milwaukee in 2014. Sunday, October 5 @ 2 p.m. Tuesday, October 7 @ 8 p.m. Canadian Stage's production ran from April 7 to May 4, Wednesday, October 8 @ 8 p.m. -

David Mamet's Drama, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Three Iconic Forerunners

Ad Americam. Journal of American Studies 20 (2019): 5-14 ISSN: 1896-9461, https://doi.org/10.12797/AdAmericam.20.2019.20.01 Robert J. Cardullo University of Kurdistan, Hewlêr [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0816-9751 The Death of Salesmen: David Mamet’s Drama, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Three Iconic Forerunners This essay places Glengarry Glen Ross in the context of David Mamet’s oeuvre and the whole of American drama, as well as in the context of economic capitalism and even U.S. for- eign policy. The author pays special attention here (for the first time in English-language scholarship) to the subject of salesmen or selling as depicted in Mamet’s drama and earlier in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, and Tennes- see Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire—each of which also features a salesman among its characters. Key words: David Mamet; Glengarry Glen Ross; American drama; Selling/salesmanship; Americanism; Death of a Salesman; The Iceman Cometh; A Streetcar Named Desire. Introduction: David Mamet’s Drama This essay will first placeGlengarry Glen Ross (1983) in the context of David Mamet’s oeuvre and then discuss the play in detail, before going on to treat the combined subject of salesmen or selling, economic capitalism, and even U.S. foreign policy as they are depicted or intimated not only in Glengarry but in earlier American drama (a subject previously undiscussed in English-language scholarship). I am thinking here of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949), Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Co- meth (1946), and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire (1947)—each of which also features a salesman among its main characters. -

Download the Press Release

New Work ● Local Talent ● Always Affordable Tickets For Immediate Release Contact: Mike Clary [email protected] 518-267-0683 May 24, 2021 GREAT BARRINGTON PUBLIC THEATER PLANS SUMMER OF HEARTFELT COMEDY, LITERARY DELIGHT AND MASTERFUL SUSPENSE. THREE NEW PLAYS, ON TWO STAGES, PLUS WET INK READINGS AND SOLO PERFORMANCES. From late June to early August, Great Barrington Public Theater will bring a diverse six-weeks to the Daniel Arts Center, at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, Great Barrington. Keeping with the Public’s core mission, the 2021 program spotlights original work and new voices, largely comprised of local area talent. Tickets will remain affordable to all, between $20 and $40. “After several months eagerly looking forward to reopening, we have finalized plans for a powerful trio of fully-staged new plays by well-known and respected writers, featuring many of our most lovable, notable Berkshire actors, along with a selection of captivating solo-artist performances that will delight and surprise everyone,” Artistic Director Jim Frangione said. “As disappointing as the forced hiatus has been, we are all excited to get back into the theater.” “We welcome everyone in the Berkshires and beyond to come out, come back, be safe, comfortable, and join us for an exhilarating and lively summer,” Deann Simmons Halper, Executive Director said. “We’re presenting top-tier new plays and excellent artists to all audiences and looking forward to a rejuvenating season of fantastic theater on two stages.” The Public’s schedule opens at the Daniel Art Center mainstage McConnell Theater, June 24-July 3 with DAD, a poignant, heartfelt and humorous new jewel of a comedy by Mark St. -

An Actor's Journey of Creating the Character of Jack Lawson from David Mamet's Race

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-15-2012 Pigments of Imagination: An Actor's Journey of Creating the Character of Jack Lawson from David Mamet's Race Paxton H. McCaghren [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Acting Commons Recommended Citation McCaghren, Paxton H., "Pigments of Imagination: An Actor's Journey of Creating the Character of Jack Lawson from David Mamet's Race" (2012). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1600. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1600 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pigments of Imagination: An Actor’s Journey of Creating the Character of Jack Lawson from David Mamet’s Race A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Film, Theatre, Communication Arts Theatre Performance by Paxton H. -

French and Francophone Narratives of Race and Racism

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Writing Verdicts: French And Francophone Narratives Of Race And Racism Andrea Lloyd University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Lloyd, Andrea, "Writing Verdicts: French And Francophone Narratives Of Race And Racism" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3538. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3538 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3538 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writing Verdicts: French And Francophone Narratives Of Race And Racism Abstract Inspired by Didier Eribon's La société comme verdict, this dissertation examines how the novelistic representation of racism and racialization in French-language texts can push back against a collective social verdict in France that stigmatizes non-white peoples as lesser and as other. Though discussing the existence of race is still taboo in France, I show that this stigmatization is in fact a racial verdict, or one that operates through racialization, as opposed to a verdict predicated on sexuality, gender, or class. To do so, I analyze the representation of racial hierarchies and the experience of racism in six novels written in French: Daniel Biyaoula's L'Impasse, Gisèle Pineau's L'Exil selon Julia, Leïla Sebbar's Le Chinois vert d'Afrique, Zahia Rahmani's "Musulman" roman, Cyril Bedel's Sale nègre, and Bessora's 53 cm. As I argue, these authors resist racial verdicts by writing about and examining the place of the ethnic minority individual in French society. In so doing they also issue counter verdicts that condemn society, individuals, and the state for their complicity in maintaining an unjust status quo. -

USC Visions & Voices: November

Visions and Voices and the USC Libraries have collaborated to create a series of resource guides that allow you to build on your experiences at many Visions and Voices events. Explore the resources listed below and continue your journey of inquiry and discovery! NOVEMBER USC LIBRARIES RESOURCE GUIDE The end of the line for an unpopular president is the inauguration of hilarity when Pulitzer Prize winner David Mamet (Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo, Race) makes the Oval Office a three-ring circus of political incorrectness. President Charles Smith is desperate to be reelected. And he’s not afraid to beg, bargain or sacrifice the remains of his integrity to achieve this. The only question is: will he save the turkeys or marry the lesbians? The answer is classic Mamet. KEN KLEIN of the USC Libraries has selected the following resources to help you learn more about Mamet and his work. Visit the online version of this guide at libguides.usc.edu/November for even more resources. Introduction Just three-and-a-half weeks before the national elections, Visions and Voices offers a chance to see November, David Mamet’s 2008 play on presidential election politics, at the Los Angeles Music Center’s Mark Taper Forum. Selected Plays by David Mamet Selected Electronic Resources American Buffalo (1977) Find scholarly sources about Mamet and his plays By David Mamet through these electronic resources, accessible through Leavey Library: P S 3 5 6 3 . A 4 3 4 5 A 8 1 9 7 7 the USC Libraries homepage at www.usc.edu/libraries. -

Audience and the African American Playwright

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Audience and the African American playwright : an analysis of the importance of audience selection and audience response on the dramaturgies of August Wilson and Ed Bullins Ladrica C. Menson-Furr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Menson-Furr, Ladrica C., "Audience and the African American playwright : an analysis of the importance of audience selection and audience response on the dramaturgies of August Wilson and Ed Bullins" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2467. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2467 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AUDIENCE AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN PLAYWRIGHT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE IMPORTANCE OF AUDIENCE SELECTION AND AUDIENCE RESPONSE ON THE DRAMATURGIES OF AUGUST WILSON AND ED BULLINS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Ladrica C. Menson-Furr B.A., Spelman College, 1993 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1995 May 2002 DEDICATION To Mark, Morgan and Mama (Gwendolyn Menson) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS So many people have touched my life as I have toiled through this process that I could simply write one sentence saying, “Thank you to all those persons who believed in me, when I did not believe in myself.” However, I wish to attempt to list them all as a way to let them know that their assistance, prayers and support will always be inscribed on my heart. -

An Analysis of Three Plays by David Mamet Through the Lens of Kirkian Conservatism

PROTECT, PRESERVE, AND REFORM: AN ANALYSIS OF THREE PLAYS BY DAVID MAMET THROUGH THE LENS OF KIRKIAN CONSERVATISM Jennifer Shadle A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Angela Ahlgren, Advisor Jonathan Chambers © 2018 Jennifer Shadle All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Ahlgren, Advisor American playwright David Mamet announced his conservatism in 2004 through an article in The Village Voice. While many of his plays have inspired scholarship, especially regarding the use of unethical business practices in his work, analyses of the influence of his conservatism are rare. With a mixed methodology of character and literary analysis, through a lens of Kirkian conservatism, I examine the implications of conservative themes in character interactions in three of David Mamet’s plays. Specifically, I explore the mentor/student relationship in American Buffalo (1975), the spirit or potential of the individual in Glengarry Glen Ross (1984), and natural law and justice in The Anarchist (2012). I found that a question at the heart of conservatism, what must be preserved, protected, and reformed so that society may progress, was also a vital component to Mamet’s work. It is my hope that my study will expand existing scholarship about the philosophies of playwrights, and that I might provide a voice to a previously unexplored group in theatre. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, to my advisor, Angela Ahlgren, I would like to convey my gratitude. Her wisdom and thoughtful questions were invaluable in crafting this study, and I can’t properly express my appreciation for all the ways she pushed me to think more intently about Mamet and Kirk. -

From: Heidi J

From: Heidi J. Dallin, Media Relations Director Phone: Office: 978-281-4099/Home: 978-283-6688 Email: [email protected] Gloucester Stage Announces New Leadership Team Artistic Director Robert Walsh and Managing Director Jeff Zinn Join Forces To Lead Gloucester Stage Gloucester Stage Board of Directors President Robert Boulrice is pleased to announce that longtime New England theatre professionals Robert Walsh and Jeff Zinn have been named the new Artistic Director and Managing Director of the 36 year old non profit professional theatre, effective immediately. Jeff Zinn makes his Gloucester Stage debut as Managing Director while Walsh’s appointment as Artistic Director continues a 20-year relationship with Gloucester Stage as both an actor and director as well as serving as Interim Artistic Director since December, 2014. During Gloucester Stage’s 2015 season Walsh directed Enda Walsh's The New Electric Ballroom and currently appears in the New England premiere of Israel Horovitz's Gloucester Blue, which has extended it run through October 11. Regarding the Artistic Director appointment Boulrice explains, “This summer we conducted an exhaustive national search that generated 86 applicants. I am delighted to say that after a whole lot of work, all we had to do was remove the “Interim” tag from Bob Walsh’s Artistic Director title! The cream rose to the top, and it was locally churned.” Reflecting on Walsh’s accomplishments as Interim Artistic Director, Boulrice continues, “Bob has been at the artistic helm for the entire 2015 season. Many patrons have commented that this has been our best season ever. He is already at work finding plays for our next season, news of which we want to tease our audiences with before the 2015 season ends. -

Mamet on Mamet: Politics and Poetics in Oleanna, Race, The

MAMET ON MAMET: POLITICS AND POETICS IN OLEANNA, RACE, THE ANARCHIST, AND CHINA DOLL A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by JAMES MICHAEL ALDERISO B.A., Wilkes University, 2014 Kansas City, Missouri 2016 © 2016 JAMES MICHAEL ALDERISO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MAMET ON MAMET: POLITICS AND POETICS IN OLEANNA, RACE, THE ANARCHIST, AND CHINA DOLL James Michael Alderiso, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2016 ABSTRACT Mamet on Mamet: Politics and Poetics in Oleanna, Race, The Anarchist, and China Doll” aims to illuminate Mamet’s mature aesthetic through a close examination of four of his later plays. The thesis blends textual examinations of the plays with reporting on major, commercial productions of them. The combination of the two modes yields insights about current perceptions of David Mamet’s place in the American theatre. In every chapter, Mamet’s The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture (2011)—a work of nonfiction by the playwright—is referenced to further highlight the themes of the play and the playwright. However, the first chapter “David Mamet and the Eight Selling Playwrights of the Twenty-first Century” is an introductory chapter that establishes Mamet’s canonical status in the theatre, within the pantheon of playwrights who are commercially reliable. The final chapter “Lions in Winter: China Doll” follows iii the format of the middle chapters, except for the primary account of attending the world premiere of the play at the Gerald Shoenfeld Theatre on Broadway in New York. -

The Anarchist by David Mamet West Coast Premiere Starring Velina Brown* and Tamar Cohn Directed by John Fisher January 2

LAWRENCE HELMAN PUBLIC RELATIONS – E MAIL - [email protected] Tel. 415 /661- 1260 / Cell. 415/ 336- 8220 (DO NOT PUBLISH THIS #) FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Nov. 17, 2014 For press materials and hi-res color press photos, visit: http://www.therhino.org/press.htm (press materials available by Dec. 8, 2014) Theatre Rhinoceros presents… The Anarchist by David Mamet West Coast Premiere Starring Velina Brown* and Tamar Cohn Directed by John Fisher January 2 – 17, 2015 - Limited Engagement - 15 Performances Only! Wed. - Sat. - 8:00 pm / Sat. Matinees - 3:00 pm (Sun. Jan 4: Matinee 3:00 pm; and Sunday evening show - 7:00 pm.) Previews Jan. 2 & 3 (Fri.- 8 pm) & (Sat. - 3 pm Matinee) – Opens Sat. Jan. 3 - 8:00 pm Eureka Theatre in SF www.TheRhino.org *Member Actor’s Equity Association “Mr. Mamet has always been preoccupied with words both as power tools and as camouflage. That’s true whether the language is lowdown (as in “Glengarry” and “American Buffalo”) or high-flown (as in “Oleanna”). This has often involved a certain verbal self-consciousness among his characters. But it has never been as acute as in “The Anarchist,” in which both women are especially aware of words as instruments of misdirection and what Cathy calls the opacity of human motives.”- Ben Brantley NY Times Review (excerpt) Dec. 2012 The Anarchist by David Mamet will have its California premiere in this exclusive Theatre Rhinoceros production in San Francisco for a limited engagement – 15 performances only! The show plays Jan. 2 – 17, 2015 - Wed. - Sat. - 8:00 pm / Sat.