An Analysis of Three Plays by David Mamet Through the Lens of Kirkian Conservatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Ebook Download the Plays, Screenplays and Films of David

THE PLAYS, SCREENPLAYS AND FILMS OF DAVID MAMET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Price | 192 pages | 01 Oct 2008 | MacMillan Education UK | 9780230555358 | English | London, United Kingdom The Plays, Screenplays and Films of David Mamet PDF Book It engages with his work in film as well as in the theatre, offering a synoptic overview of, and critical commentary on, the scholarly criticism of each play, screenplay or film. You get savvy industry tips and strategies for getting your screenplay noticed! Mamet is reluctant to be specific about Postman and the problems he had writing it, explaining. He shrugs off the whispers floating up and down the Great White Way about him selling out and going Hollywood. Contemporary playwright David Mamet's thought-provoking plays and screenplays such as Wag the Dog , Glengarry Glen Ross for which he won the Pulitzer Prize , and Oleanna have enjoyed popular and critical success in the past two decades. The Winslow Boy, Mamet's revisitation of Terence Rattigan's classic play, tells of a thirteen-year-old boy accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order and the tug of war for truth that ensues between his middle-class family and the Royal Navy. House of Games is a psychological thriller in which a young woman psychiatrist falls prey to an elaborate and ingenious con game by one of her patients who entraps her in a series of criminal escapades. Paul Newman plays Frank Calvin, an alcoholic and disgraced Boston lawyer who finds a shot at redemption with a malpractice case. I Just Kept Writing. The impressive number of essays , novels , screenplays , and films that Mamet has produced They might be composed and awesome on the battlefield, but there is a price, and that is their humanity. -

Advertising Sales

"It is a thrill to see David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross” on this season’s theater roster..." -- Lansing City Pulse August 12, 2015 "...even the silent moments grab the audience and keep them intently focused." --Bridgette Redman, Encore Michigan review of Ixion's Topdog/Underdog "...a thrill to watch." --Tom Helma, Lansing City Pulse review of Ixion's The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds Be a part of the excitement! Advertise with Ixion After a critically acclaimed inaugural season, Ixion theatre ensemble is diving into its second. Featuring world and regional premieres, and a dynamic revival; this season promises to entertain, challenge and excite audiences. Equally exciting is our new home, the Robin Theater. Seating nearly a hundred people per performance, this space offers an intimate opportunity to enjoy the arts. You can be a part of our second season by advertising in our show programs. Imagine connecting with a dynamic arts organization; their patrons committed to Sineh Wurie the community; and celebrating the revitalization of Lansing's REO Town! Nominated for Best Lead Actor by Lansing City Pulse & Encore Michigan in Attached is an advertising order sheet, which details ad specs and pricing. Please Topdog/Underdog contact us if you have any questions. If you are interested in underwriting a particular show or discussing other advertising opportunities, please contact our Artistic Director, jeff croff, via phone, 715.775.4246, or email [email protected]. www.ixiontheatre.com Find us on Facebook and Google+ -

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

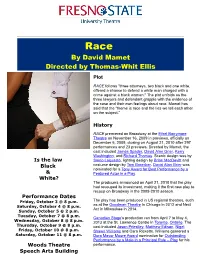

Race by David Mamet Directed by Thomas-Whit Ellis Plot

Race By David Mamet Directed by Thomas-Whit Ellis Plot RACE follows "three attorneys, two black and one white, offered a chance to defend a white man charged with a crime against a black woman." The plot unfolds as the three lawyers and defendant grapple with the evidence of the case and their own feelings about race. Mamet has said that the "theme is race and the lies we tell each other on the subject." History RACE premiered on Broadway at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on November 16, 2009 in previews, officially on December 6, 2009, closing on August 21, 2010 after 297 performances and 23 previews. Directed by Mamet, the cast included James Spader, David Alan Grier, Kerry Washington, and Richard Thomas. Scenic design was by Is the law Santo Loquasto, lighting design by Brian MacDevitt and Black costume design by Tom Broecker. David Alan Grier was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Performance by a & Featured Actor in a Play. White? The producers announced on April 21, 2010 that the play had recouped its investment, making it the first new play to recoup on Broadway in the 2009-2010 season. Performance Dates Friday, October 3 @ 8 p.m. The play has been produced in US regional theatres, such Saturday, October 4 @ 8 p.m. as at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago in 2012 and Next Act in Milwaukee in 2014. Sunday, October 5 @ 2 p.m. Tuesday, October 7 @ 8 p.m. Canadian Stage's production ran from April 7 to May 4, Wednesday, October 8 @ 8 p.m. -

David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521894689 - The Cambridge Companion to David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More information 1 CHRISTOPHER BIGSBY David Mamet In 1974, a play set in part in a singles bar, laced with obscene language and charged with a seemingly frenetic energy, was voted Best Chicago Play. Transferred to Off Off and Off Broadway it picked up an Obie Award. Sexual Perversity in Chicago was not David Mamet’s first play, but it did mark the beginning of a career that would astonish in both its range and depth. The following year American Buffalo opened at Chicago’s Goodman The- atre in an “alternative season.” It was well received and opened on Broadway fifteen months later where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. It ran for 135 performances, hardly a failure but in the hit or miss world of New York, not a copper-bottomed success either. Nonetheless, in three years he had announced his arrival in unequivocal terms. David Mamet came as something of a shock, not least because his first public success, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, seemed brutally direct in terms of its language and subject, as did American Buffalo. But it was already clear to many that here was a distinctive talent, albeit one that some critics found difficult to assess, not least because of his characters’ scatological language and fractured syntax, along with the apparent absence, in his plays, of a conventional plot. They praised what they took to be his linguistic naturalism, as though his intent had been to offer an insight into the cultural lower depths while capturing the precise rhythms of contemporary speech (though he did invoke Gorky’s The Lower Depths as being, like a number of his own plays, a study in stasis). -

Spring Vis Kicks Off with Multicultural Events

-------- ---- - -- PARTLY Editorial Friday CLOUDY Notre Dame and South Bend could benefit from the HIGH 42° purchase of St. Joseph Regional Medical Center. APRIL 5, LOW25° Viewpoint+ page 12 2002 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL. XXXV NO. 116 HTTP://OBSERVER.ND.EDU Spring Vis kicks off with multicultural events • Models to strut the • Latin Expressions latest fashions at the educates, entertains Black Cultural Arts through music, dance Council fashion show and culture By MAUREEN SMITH£ By MAUREEN SMITH£ Senior Staff Writer Senior StaffWriter Though Saturday night's 25th annual Black Showcasing a wide variety of Latin music, Cultural Arts Council Fashion Show may be dance and culture, Latin Expressions kicks sponsored by a campus minority organiza off tonight at Saint Mary's O'Laughlin tion, coordinators want to make one thing Auditorium. clear: everyone is invited. Acts ranging from traditional Mexican folk "It's open to everyone. It's not an all-black dances to student renditions of favorite thing," said coordinator Andrea de Vries. Latino pop songs and choreographed dance "The models are white, Asian, Hispanic, numbers will keep the show tightly focused Black. It's a very inclusive event." on Latino culture. Titled "Noche de Ritmo Unlike years past, the coordinators wanted Latino," the event aims to educate and enter to bring a tighter focus to this year's show. tain. Uniting the scenes together with one com "We recognize that there are lots of talent mon thread was a challenge de Vries gladly ed people on campus, and they should be took on with fellow organizer Margaret allowed to showcase their talent but this Mason. -

T Wentieth Centur Y North Amer Ican Drama

TWENTIETH CENTURY NORTH AMERICAN DRAMA, SECOND EDITION learn more at at learn more alexanderstreet.com Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition contains 1,900 plays from the United States and Canada. In addition to providing a comprehensive full-text resource for students in the performing arts, the collection offers a unique window into the econom- ic, historical, social, and political psyche of two countries. Scholars and students who use the database will have a new way to study the signal events of the twentieth century – including the Depression, the role of women, the Cold War, and more – through the plays and performances of writers who lived through these decades. More than 1,250 of the works are in copyright and licensed Jules Feiffer, Neil LaBute, Moisés Kaufman, Lee Breuer, Richard from the authors or their estates, and 1,700 plays appear in Foreman, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Horton Foote, Romulus Linney, no other Alexander Street collection. At least 550 of the works David Mamet, Craig Wright, Kenneth Lonergan, David Ives, Tina have never been published before, in any format, and are Howe, Lanford Wilson, Spalding Gray, Anna Deavere Smith, Don available only in Twentieth Century North American Drama, DeLillo, David Rabe, Theresa Rebeck, David Henry Hwang, and Second Edition – including unpublished plays by major writers Maria Irene Fornes. and Pulitzer Prize winners. Besides the mainstream works, users will find a number of plays Important works prior to 1920 are included, with the concentration of particular social significance, such as the “people’s theatre” of works beginning with playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill, exemplified in performances by The Living Theatre and The Open Elmer Rice, Sophie Treadwell, and Susan Glaspell in the 1920s Theatre. -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

(XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: the UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 Min

November 8, 2016 (XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: THE UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot url links.) DIRECTED BY Brian De Palma WRITING CREDITS David Mamet (written by), Oscar Fraley & Eliot Ness (suggested by book) PRODUCED BY Art Linson MUSIC Ennio Morricone CINEMATOGRAPHY Stephen H. Burum FILM EDITING Gerald B. Greenberg and Bill Pankow Kevin Costner…Eliot Ness Sean Connery…Jimmy Malone Charles Martin Smith…Oscar Wallace Andy García…George Stone/Giuseppe Petri Robert De Niro…Al Capone Patricia Clarkson…Catherine Ness Billy Drago…Frank Nitti Richard Bradford…Chief Mike Dorsett earning Oscar nominations for the two lead females, Piper Jack Kehoe…Walter Payne Laurie and Sissy Spacek. His next major success was the Brad Sullivan…George controversial, ultra-violent film Scarface (1983). Written Clifton James…District Attorney by Oliver Stone and starring Al Pacino, the film concerned Cuban immigrant Tony Montana's rise to power in the BRIAN DE PALMA (b. September 11, 1940 in Newark, United States through the drug trade. The film, while New Jersey) initially planned to follow in his father’s being a critical failure, was a major success commercially. footsteps and study medicine. While working on his Tonight’s film is arguably the apex of De Palma’s career, studies he also made several short films. At first, his films both a critical and commercial success, and earning Sean comprised of such black-and-white films as Bridge That Connery an Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor (the only Gap (1965). He then discovered a young actor whose one of his long career), as well as nominations to fame would influence Hollywood forever.