Levee Decisions and Sustainability for the Delta Technical Appendix B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter R. Mclean Papers, Bulk 1930-1968

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7779n9g3 No online items Inventory of the Walter R. McLean Papers, bulk 1930-1968 Processed by the Water Resources Collections and Archives staff. Water Resources Collections and Archives Orbach Science Library, Room 118 PO Box 5900 University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Phone: (951) 827-2934 Fax: (951) 827-6378 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/wrca © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Walter R. MS 76/7 1 McLean Papers, bulk 1930-1968 Inventory of the Walter R. McLean Papers, bulk 1930-1968 Collection number: MS 76/7 Water Resources Collections and Archives University of California, Riverside Riverside, California Contact Information: Water Resources Collections and Archives Orbach Science Library, Room 118 PO Box 5900 University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Phone: (951) 827-2934 Fax: (951) 827-6378 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/wrca Processed by: Water Resources Collections and Archives staff Date Completed: October 1976 © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Walter R. McLean Papers, Date (inclusive): bulk 1930-1968 Collection number: MS 76/7 Creator: McLean, Walter Reginald, 1903- Extent: ca. 19 linear ft. (40 boxes) Repository: Water Resources Collections and Archives Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Shelf location: Water Resources Collections and Archives. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Water Resources Collections and Archives. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Archives. -

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

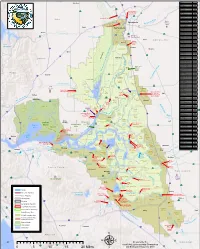

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

Spatial Variability of Levees As Measured Using the CPT

2nd International Symposium on Cone Penetration Testing, Huntington Beach, CA, USA, May 2010 Spatial Variability of Levees as Measured Using the CPT R.E.S. Moss Assistant Professor, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo J. C. Hollenback Graduate Researcher, U.C. Berkeley J. Ng Undergraduate Researcher, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo ABSTRACT: The spatial variability of a soil deposit is something that is commonly discussed but difficult to quantify. The heterogeneity as a function of lateral distance can be critical to the design of long engineered structures such as highways, bridges, levees, and other lifelines. This paper presents a methodology for using CPT mea- surements to quantifying the spatial variability of cone tip resistance along a levee in the California Bay Delta. The results, presented in the form of a general relative va- riogram, identify the distance at which the maximum spatial variability is achieved for a given soil strata. This information helps define minimally correlated stretches of levee for proper failure and risk analysis. Presented herein are methods of interpret- ing, calculating, and analyzing CPT data to arrive at the quantified spatial variability with respect to different static and seismic failure modes common to levee systems. 1 INTRODUCTION Spatial variability of engineering properties in soil strata is inherent to the nature of soil. Spatial variability is controlled primarily by the depositional environment where high energy systems usually deposit materials with high spatial variability (e.g. al- luvial gravels) and low energy systems usually deposit materials with low spatial va- riability (e.g. lacustrine clays). This spatial variability is generally taken into account in geotechnical design in a qualitative empirical manner through appropriately spaced borings to assess the changing subsurface conditions. -

San Joaquin River Riparian Habitat Below Friant Dam: Preservation and Restoration1

SAN JOAQUIN RIVER RIPARIAN HABITAT BELOW FRIANT DAM: PRESERVATION AND RESTORATION1 Donn Furman2 Abstract: Riparian habitat along California's San Joa- quin River in the 25 miles between Friant Darn and Free- Table 1 – Riparian wildlife/vegetation way 99 occurs on approximately 6 percent of its his- corridor toric range. It is threatened directly and indirectly by Corridor Corridor increased urban encroachment such as residential hous- Category Acres Percent ing, certain recreational uses, sand and gravel extraction, Water 1,088 14.0 aquiculture, and road construction. The San Joaquin Trees 588 7.0 River Committee was formed in 1985 to advocate preser- Shrubs 400 5.0 Other riparianl 1,844 23.0 vation and restoration of riparian habitat. The Com- Sensitive Biotic2 101 1.5 mittee works with local school districts to facilitate use Agriculture 148 2.0 of riverbottom riparian forest areas for outdoor envi- Recreation 309 4.0 ronmental education. We recently formed a land trust Sand and gravel 606 7.5 called the San Joaquin River Parkway and Conservation Riparian buffer 2,846 36.0 Trust to preserve land through acquisition in fee and ne- Total 7,900 100.0 gotiation of conservation easements. Opportunities for 1 Land supporting riparian-type vegetation. In increasing riverbottom riparian habitat are presented by most cases this land has been mined for sand and gravel, and is comprised of lands from which sand and gravel have been extracted. gravel ponds. 2 Range of a Threatened or Endangered plant or animal species. Study Area The majority of the undisturbed riparian habitat lies between Friant Dam and Highway 41 beyond the city limits of Fresno. -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is twofold: to provide general information for anyone interested in the California islands and to serve as a field guide for visitors to the islands. The book covers both general history and nat- ural history, from the geological origins of the islands through their aboriginal inhabitants and their marine and terrestrial biotas. Detailed coverage of the flora and fauna of one island alone would completely fill a book of this size; hence only the most common, most readily observed, and most interesting species are included. The names used for the plants and animals discussed in this book are the most up-to-date ones available, based on the scientific literature and the most recently published guidebooks. Common names are always subject to local variations, and they change constantly. Where two names are in common use, they are both mentioned the first time the organism is discussed. Ironically, in recent years scientific names have changed more recently than common names, and the reader concerned about a possible discrepancy in nomenclature should consult the scientific literature. If a significant nomenclatural change has escaped our notice, we apologize. For plants, our primary reference has been The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, edited by James C. Hickman, including the latest lists of errata. Variation from the nomenclature in that volume is due to more recent interpretations, as explained in the text. Certain abbreviations used throughout the text may not be immedi- ately familiar to the general reader; they are as follows: sp., species (sin- gular); spp., species (plural); n. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

RD799 Five Year Plan

Reclamation District 799 Five Year Capital Improvement Plan May 2012 Prepared by 2365 Iron Point Road, Suite 300 Folsom, CA 95630 This page intentionally left blank. RD 799 Five Year Plan Contents 1.0 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Brief History of Hotchkiss Tract .......................................................................................... 3 2.1 Location .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Geomorphic Evolution ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Historical Flood Events ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 Existing level of protection ........................................................................................................... 6 3.0 Identification of Need for Improvements to Alleviate or Minimize Existing Hazards ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3.1 Local Assets ....................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Non-local Assets and Public Benefit .................................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies.