Bar Council Response to the Looking to the Future- Flexibility and Public Protection Consultation Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Career at the Commercial Bar “…A Career Like No Other with Opportunities Like No Other …”

A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR “…a career like no other with opportunities like no other …” 2 A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR What is the Commercial Bar? 5 Why should you choose a career 6 at the Commercial Bar? Myths about the Commercial Bar 8 How to qualify as a barrister at the 12 Commercial Bar Useful websites 19 3 “…the front line of advocacy …” 4 WHAT IS THE COMMERCIAL BAR? he independent Bar is a law in which commercial issues arise, specialist referral profession including public law, professional Toffering expert legal advice and negligence, intellectual property, advocacy. Barristers practising at media and entertainment law and the independent Bar are self- construction. Individuals may employed but (in most cases) group specialise in particular areas within together into sets of chambers for the broad field of commercial law, and the purpose of sharing premises and specialism tends to increase other overheads. with seniority. As the law has become more complex, members of the Bar have ‘Commercial law is perhaps tended to specialise in particular areas and to form Specialist Bar best summed up as the law Associations (SBAs), of which COMBAR which applies to business is one. COMBAR now has over 1,200 members with 36 member sets of and financial disputes.’ chambers and individual members from 21 sets across London, Liverpool, Commercial barristers are usually Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol instructed by solicitors rather than and Devon. by a client directly; the services they provide fall into two main areas. First, The members of COMBAR practise and most importantly, a barrister commercial law, which is a broad is a specialist advocate who will term encompassing a wide range of present the client’s case in court. -

Career Options with Your LLM

Career Options with your LLM Introduction Every student will have individual reasons for undertaking the LLM qualification. These may include enhancing or broadening career opportunities or adding value and depth to their CV. This leaflet aims to outline the main job opportunities open to LLM students, provide information on how to research opportunities and signpost further support. What skills does an LLM develop? As well as intellectual skills and professional expertise in a specialist area of law (e.g. Maritime, International Commercial Law) the LLM course also enables you to develop a range of transferable skills which are useful in whatever career path you choose to pursue. These include legal research and writing, analysis, critical evaluation and logical thinking as well as written and verbal communication. What types of careers can LLM graduates consider? UK Legal Market As every student has a different background and experience there is no single route to qualifying or working in the UK legal market. You will have to research the routes available and determine which of these is relevant and appropriate for you. Solicitor Qualifying as a solicitor currently requires completing a Legal Practice Course (LPC) followed by a two-year Training Contract. Depending on your previous experience and qualifications, you may have to complete a conversion course known as a Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) before undertaking the LPC. However, you should note that the GDL and LPC will be replaced by a super-exam, the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE), due to be introduced in 2020. The SQE will introduce a more flexible approach to work-based experience and will no longer require students to sign up for the GDL or LPC. -

Solicitor Not on the Record

Solicitor not on the record Purpose: To provide assistance to barristers who find out that their solicitor is not on the court record Scope of application: All practising barristers Issued by: The Ethics Committee Issued: April 2019 Last reviewed: May 2020 Status and effect: Please see the notice at end of this document. This is not “guidance” for the purposes of the BSB Handbook I6.4. Issue: a barrister is instructed by an instructing solicitor to represent a lay client at a hearing. The barrister is told or finds out that the solicitor is not on the court record. What should the barrister do? Answer: nothing. 1. A barrister can provide reserved legal activities (including advocacy at court) if s/he is instructed by a professional client, a licensed access client or a public access client. There is nothing in the BSB Handbook or the Legal Services Act which requires that the person instructing the barrister to attend court must have conduct of the litigation. 2. Indeed, it is axiomatic that when a barrister is instructed by a licensed access client, the licence holder will not have conduct of the litigation. The same applies in a public access case when the barrister is instructed by an intermediary. 3. The Law Society recognises that solicitors may act for a client on a limited retainer. This is called ‘unbundling’. It is usually so that the client can save money. The Law Society guidance1 says: ‘The essence of unbundling in its purest form is that 1 At the time of review in May 2020, the Law Society guidance was awaiting updating to reflect the replacement of the SRA Handbook (version 21) by the SRA Standards and Regulations on, and with effect, from 25th November 2019. -

CPS Advocate Panel Scheme 2016 – 2020

CPS Advocate Panel Scheme 2016 – 2020 CROWN PROSECUTION SERVICE – ADVOCATE PANEL SCHEME 2016 - 2020 DETAILS OF THE SCHEME – GENERAL CRIME AND THE RAPE AND CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE LIST (‘the RAPE List’) (UPDATED JULY 2019) Background 1. The CPS Advocate Panel (‘the 2012 Panel’) came into effect in February 2012 and the central Specialist Panels followed in April 2013. 2. The CPS Advocate Panel arrangements established a time limited list of quality assured advocates to undertake criminal prosecution advocacy for CPS in the Crown Court and Higher Courts. 3. The 2016 Panel will operate from 2016 to 2020. This document describes the aims and purpose of the 2016 Panel. 4. In addition to the General Crime and the Rape and Child Sexual Abuse List (‘Rape List’), the CPS has separate arrangements relating to the central Specialist Panels, which run from 2018 to 2022 and relate to the following areas of casework: • Counter Terrorism Panel • Extradition Panel • Fraud Panel (including fiscal fraud) • Serious Crime Group Panel • Proceeds of Crime Panel Aim 5. The aim of the Panel arrangements is to appoint advocates who have met the selection criteria and have relevant, up to date skills and experience. Any advocate appointed must be able to deliver high quality prosecution advocacy services and have a commitment to meet the aims and objectives of the CPS. 6. The CPS requires that all prosecution advocates provide advocacy services of the highest quality. This extends beyond technical ability and includes attitudes and behaviours. All advocates instructed by the CPS, whether in-house or external, will be expected to behave in accordance with published CPS values, which are: To be independent and fair a. -

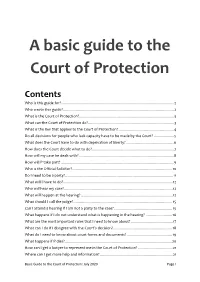

A Basic Guide to the Court of Protection

A basic guide to the Court of Protection Contents Who is this guide for? ................................................................................................................ 2 Who wrote this guide? .............................................................................................................. 2 What is the Court of Protection? .............................................................................................. 3 What can the Court of Protection do? ..................................................................................... 3 What is the law that applies to the Court of Protection? ....................................................... 4 Do all decisions for people who lack capacity have to be made by the Court? .................... 5 What does the Court have to do with deprivation of liberty? ................................................ 6 How does the Court decide what to do? ................................................................................. 7 How will my case be dealt with? .............................................................................................. 8 How will P take part? ................................................................................................................ 9 Who is the Official Solicitor? ................................................................................................... 10 Do I need to be a party? ........................................................................................................... 11 -

(JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT) Complaint No. 01 Of

Form No: HCJD/C-121 ORDER SHEET IN THE ISLAMABAD HIGH COURT, ISLAMABAD (JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT) Complaint No. 01 of 2021 The Registrar, Islamabad High Court, Islamabad Vs. Naseer Ahmed Kayani Advocate and others S. No. of Date of order/ Order with signature of Judge and that of parties or counsel where order/ proceedings necessary. proceedings 03) 02-03-2021. M/s Rabi bin Tariq, Daniyal Hassan, Muhammad Atif and Majid Rashid Khan, State Counsels. M/s Muhammad Umair Baloch, Asif Tamboli, and Jahangir Khan Jadoon Advocates. ATHAR MINALLAH, CJ.-These proceedings have been initiated pursuant to the powers and to fulfill the requirements under section 41 read with section 54 of the Legal Practitioners and Bar Councils Act 1973 [hereinafter referred to as the “Act of 1973”], read with the Pakistan Legal Practitioners Bar and Councils Rules, 1976 [hereinafter referred to as the “Rules of 1976”] and the Islamabad Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules, 2017 [hereinafter referred to as the “Rules of 2017”] regarding sending complaints to the respective regulatory authorities. In compliance with the mandate of sub section (1) of section 54, notices were ordered to be served on the respondents vide order, dated 18.02.2021. Two written replies have been received. Some of the respondents are reported to have Page | 2 Complaint No. 01/2021. concealed themselves to avoid the process of law because they are nominated in the criminal case registered in relation to the storming of the Islamabad High Court. Some have been arrested and sent on judicial remand. 2. It has been reported that on the morning of 8th of February, 2021, some lawyers were protesting at the District courts against the demolition of chambers by the administration of the Islamabad Capital Territory. -

Code of Conduct of the Bar of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

CODE OF CONDUCT OF THE BAR OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION Adopted by the Hong Kong Bar Association on 19 January 2017 Effective from 20 July 2017 Hong Kong Bar Association LG2, High Court 38 Queensway Hong Kong 1 © Hong Kong Bar Association 2017 All Rights of the Bar Association, the Copyright owner, are hereby reserved. This publication and/or part or parts thereof may not be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system of any nature, or transmitted in any form or by any means and whether by and through electronic or mechanical means, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written consent of the Copyright owner. The Hong Kong Bar Association is not responsible for any loss occasioned to any person whether acting or refusing to take or refraining from taking any action as a result of the material in this publication. Published in 2017 by the Hong Kong Bar Association 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER SUBJECT MATTER PARAGRAPH(S) 1. PRELIMINARY 1.1–1.7 2. DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION 2.1–2.4 3. APPLICATION 3.1–3.5 4. DISCIPLINE 4.1–4.9 5. PRACTISING BARRISTERS: GENERAL PRINCIPLES 5.1-5.20 Right to Practise 5.1-5.5 Practice as Primary Occupation 5.6-5.8 Practice from Professional Chambers 5.9-5.14 Complete Independence in Practice and Conduct as Sole Practitioners 5.15 Acting only upon Instructions from Solicitors or Other Approved Instructing Bodies or Persons 5.16-5.18 Work that should not be Undertaken by Practising Barristers 5.19 6. -

Pro Bono Practices and Opportunities in Pakistan1 I. Introduction the Pro

Pro Bono Practices and Opportunities in Pakistan 1 I. Introduction The pro bono environment in Pakistan is nascent, but is growing gradually. At present, Pakistan has a two-pronged structure for legal aid i.e. under the Pakistan Bar Council Free Legal Aid Rules, 1999 and District Legal Empowerment Committee (Constitution & Function) Rules, 2011. While the regulatory framework is present, there remains a strong need for further action amongst the legal community - there is a serious underutilization of funds allocated to institutions and committees responsible for providing legal aid, which in turn demonstrates a lack of will and resolve. The gap left by lack of implementation of the legal aid framework at a government level is to some extent filled by local and international non- governmental organizations, as well as a handful of domestic law firms, which offer legal services to the country’s underserved populations and are engaged in direct representation and broader reform work. II. Overview of Pro Bono Practices (a) Professional Regulation 1. Describe the laws/rules that regulate the provision of The practice of law in Pakistan is primarily legal services? governed by the Legal Practitioners and Bar Councils Act of 1973, last amended on 01 June 2018 (the " Bar Councils Act "). 2 The Bar Councils Act established the Pakistan Bar Council, as well as the four provincial bar councils, namely the Punjab Bar Council, the Sindh Bar Council, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Bar Council and the Baluchistan Bar Council (together, the " Provincial Bar Councils ") 3 and a bar council for the Islamabad Capital Territory, namely the Islamabad Bar Council. -

Islamabad Bar Council the Islamabad Legal

ISLAMABAD BAR COUNCIL NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th May, 2017 S.R.O. 476(I)/76— In exercise of the powers conferred by section 56 of the Legal Practitioners and Bar Councils Act 1973 (xxxv of 1973) and other enabling provisions in this behalf, the Islamabad Bar Council hereby makes and notifies the following rules: THE ISLAMABAD LEGAL PRACTITIONERS AND BAR COUNCIL RULES, 2017 (Passed by Islamabad Bar Council in its meeting held on 6th may 2017) CHAPTER – 1 PRELIMINARY 1.1 These Rules shall be called the Islamabad Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules, 2017. 1.2 . They shall come into force at once. 1.3 . In these Rules unless there is anything repugnant in the subject or context :- a) “Act” means the Legal Practitioners and Bar Councils Act, 1973; b) “Advocate-General” means the Advocate-General for Islamabad Capital Territory; c) “Bar Association” means the Islamabad District Bar Association and the Islamabad High Court Bar Association recognized as such by the Bar Council; d) “Bar Council” means the Islamabad Council; e) “Chairman” means the Chairman of the Islamabad Bar Council; f) “Committee” means a Committee constituted by the Bar Council; g) “Form” means form appended to these Rules; h) “ICT” means The Islamabad Capital Territory; i) “Member” means a member of the Islamabad Bar Council elected as such under Section 5, or who fills the vacancy of an elected member under Section 16(b); j) “Misconduct” means violation of any provision of the Act, Pakistan Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules 1976, Islamabad Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules 2017, Islamabad Bar Council Regulations 2017; and also includes non observance of any direction/ instruction of the Bar Council. -

Law for Non Law Studentsweb

Law for Non Law Students Version 8.13 You are advised to check material facts as although every effort has been made to ensure that the information given in this leaflet is up-to-date, reviews of legal education and training requirements are continually in progress and information is subject to change. Qualifications & Courses Do I need an Undergraduate Law degree to practice law? No. To practice as a solicitor or barrister in England and Wales non law graduates must first take a conversion course. Taking the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL), sometimes called the Common Professional Exam (CPE), recognised by the Solicitors Regulation Authority/Bar Standards Board, will give you the same status as a law graduate. What further courses/training do I need to do to qualify as a solicitor or barrister? Following completion of a recognised GDL/CPE you need to undertake a period of vocational training: ° Legal Practice Course (LPC) to qualify as a solicitor, followed by a two year period of work based learning, known as a training contract, including a Professional Skills course. A profile detailing the work of a solicitor training requirements and career progression is available from www.prospects.ac.uk/types_of_jobs_legal_profession.htm ° Bar Professional Training Course (BPTC) to qualify as a barrister, followed by at least 12 months pupillage. A profile detailing the work of a barrister, training requirements and career progression is available from www.prospects.ac.uk/types_of_jobs_legal_profession.htm Are there any other ways to qualify as a lawyer? Yes, becoming a legal executive is recognised by the Ministry of Justice as being one of the three core ways of becoming a lawyer. -

A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Marilyn J

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 5 Issue 3 Fall Fall 1983 A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Marilyn J. Berger Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Marilyn J. Berger, A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education, 5 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 540 (1983-1984) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Mariyn J Berger* I. INTRODUCTION The conduct of a trial in England is undeniably an impressive un- dertaking. Costume alone transports the viewer to Elizabethan time. Counsel and judges, bewigged and gowned,' appear in a cloistered, re- gal setting, strewn with leather-bound books. Brightly colored ribbons of red, green, yellow and white, rather than metal clips and staples fasten the legal papers.2 After comparison with the volatile atmosphere and often unruly conduct of a trial in a United States courtroom, it is natural to assume that the British model of courtroom advocacy pro- * B.S., 1965, Cornell University; J.D., University of California at Berkeley. Associate Profes- sor of Law, University of Puget Sound School of Law. This article is based on the author's obser- vations and interviews while a Visiting Professor of Law at the Polytechnic of the South Bank in London, 1981-82, and a scholar-in-residence at King's College, December-June, 1982. -

Acting As a Litigation Friend in the Court of Protection

Litigation Friend Guidance Guidance Note Acting as a litigation friend in the Court of Protection Author Alex Ruck Keene, Barrister, Introduction Thirty Nine Essex Street and Honorary Research Lecturer at 1. The Court of Protection plays a vital role in securing the rights of the University of Manchester some of the most vulnerable people in society. Judges of the court daily have to determine whether individuals have or lack capacity to take specific decisions, and – if they lack capacity – Table of Contents what should be done in their best interests. Introduction 1 A: Overview 2 2. The person who lacks (or may lack) capacity to take their own B: An overview of the Court of decisions will not always be involved directly in the proceedings. Protection 5 If they are, and if they do not have capacity to participate in those C: Who can be a litigation friend for proceedings, then they will need a ‘litigation friend’ – a person P in proceedings before the Court of who can conduct the proceedings on their behalf. Litigation Protection? 7 friends are therefore a crucial part of the working of the Court of D: Becoming a litigation friend and instructing lawyers 14 Protection, ensuring that those whom the proceedings concern E: What does a litigation friend do? have their voice heard before the court. F: When is it appropriate to bring a case to the Court of Protection as 3. This Guidance aims to demystify the Court of Protection generally litigation friend for P? 27 and the role of litigation friend specifically so as to enable more G: How do cases before the Court of people to consider taking up the role – thereby ensuring the Protection proceed? 33 better promotion and protection of the rights of those said to be H: When would an appointment of a lacking capacity to take their own decisions.