V:\District\GUYTON\Approved\WO 308CR165 BUIS R&R 050809.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Diocese of Harrisburg Geography of Pennsylvania

7/2006 DIOCESE OF HARRISBURG GEOGRAPHY OF PENNSYLVANIA Red Italics – Reference to Diocesan History Outcome: The student knows and understands the geography of Pennsylvania. Assessment: The student will apply the geographic themes of location, place and region to Pennsylvania today. Skills/Objectives Suggested Teaching/Learning Strategies Suggested Assessment Strategies The student will be able to: 1a. Using student desk maps, locate and highlight the 1a. On a blank map of the U.S., outline the state of state, trace rivers and their tributaries and circle Pennsylvania, label the capital, hometown and two 1. Locate and identify the state of Pennsylvania, its major cities. largest cities. capital, major cities and his hometown. On a blank map of the U.S. outline the state of 1b. Using the globe, determine the latitude and longitude Pennsylvania; within the state of Pennsylvania, outline of the state. the Diocese of Harrisburg. Label the city where the cathedral is located. 1c. Using a Pennsylvania highway map, design a road tour visiting major Pennsylvania cities. 1b. Using the desk map, identify the latitude line closest Using a Pennsylvania highway map with the counties to the hometown and two other towns of the same within the Diocese of Harrisburg marked, do the parallel of latitude. Identify the longitude nearest the following: first, in each county, identify a city or town state capital and two other towns on the same with a Catholic church; then design a road tour visiting meridian of longitude. each of these cities or towns. Using a desk map, place marks on the most-western, the most-northern, and the most-eastern tips of the Diocese 1d. -

Reception of Low Frequency Time Signals

Reprinted from I-This reDort show: the Dossibilitks of clock svnchronization using time signals I 9 transmitted at low frequencies. The study was madr by obsirvins pulses Vol. 6, NO. 9, pp 13-21 emitted by HBC (75 kHr) in Switxerland and by WWVB (60 kHr) in tha United States. (September 1968), The results show that the low frequencies are preferable to the very low frequencies. Measurementi show that by carefully selecting a point on the decay curve of the pulse it is possible at distances from 100 to 1000 kilo- meters to obtain time measurements with an accuracy of +40 microseconds. A comparison of the theoretical and experimental reiulb permib the study of propagation conditions and, further, shows the drsirability of transmitting I seconds pulses with fixed envelope shape. RECEPTION OF LOW FREQUENCY TIME SIGNALS DAVID H. ANDREWS P. E., Electronics Consultant* C. CHASLAIN, J. DePRlNS University of Brussels, Brussels, Belgium 1. INTRODUCTION parisons of atomic clocks, it does not suffice for clock For several years the phases of VLF and LF carriers synchronization (epoch setting). Presently, the most of standard frequency transmitters have been monitored accurate technique requires carrying portable atomic to compare atomic clock~.~,*,3 clocks between the laboratories to be synchronized. No matter what the accuracies of the various clocks may be, The 24-hour phase stability is excellent and allows periodic synchronization must be provided. Actually frequency calibrations to be made with an accuracy ap- the observed frequency deviation of 3 x 1o-l2 between proaching 1 x 10-11. It is well known that over a 24- cesium controlled oscillators amounts to a timing error hour period diurnal effects occur due to propagation of about 100T microseconds, where T, given in years, variations. -

Identification of Novel HPFH-Like Mutations by CRISPR Base Editing That Elevates the Expression of Fetal Hemoglobin

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.178715; this version posted July 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of novel HPFH-like mutations by CRISPR base editing that elevates the expression of fetal hemoglobin Nithin Sam Ravi1,3, Beeke Wienert4,8,9, Stacia K. Wyman4, Jonathan Vu4, Aswin Anand Pai2, Poonkuzhali Balasubramanian2, Yukio Nakamura7, Ryo Kurita10, Srujan Marepally1, Saravanabhavan Thangavel1, Shaji R. Velayudhan1,2, Alok Srivastava1,2, Mark A. DeWitt 4,5, Jacob E. Corn4,6, Kumarasamypet M. Mohankumar1* 1. Centre for Stem Cell Research (a unit of inStem, Bengaluru), Christian Medical College Campus, Bagayam, Vellore-632002, Tamil Nadu, India. 2. Department of Haematology, Christian Medical College Hospital, IDA Scudder Rd, Vellore-632002, Tamil Nadu, India. 3. Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 011, Kerala, India. 4. Innovative Genomics Institute, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California- 94704, USA. 5. Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics, University of California - Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California - 90095, USA. 6. Institute of Molecular Health Sciences, Department of Biology, ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern- Weg, Zurich - 8092, Switzerland. 7. Cell Engineering Division, RIKEN BioResource Center, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0074, Japan. 8. Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology, Gladstone Institutes, San Francisco, California -94158, USA 9. School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, University of New South Wales - 2052, Sydney, Australia. 10. Research and Development Department Central Blood Institute Blood Service Headquarters Japanese Red Cross Society, 2-1-67 Tatsumi, Tokyo, 135-8521, Japan *Corresponding Author: Dr. -

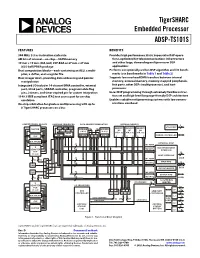

Tigersharc Embedded Processor ADSP-TS101S

TigerSHARC Embedded Processor ADSP-TS101S FEATURES BENEFITS 300 MHz, 3.3 ns instruction cycle rate Provides high performance Static Superscalar DSP opera- 6M bits of internal—on-chip—SRAM memory tions, optimized for telecommunications infrastructure 19 mm × 19 mm (484-ball) CSP-BGA or 27 mm × 27 mm and other large, demanding multiprocessor DSP (625-ball) PBGA package applications Dual computation blocks—each containing an ALU, a multi- Performs exceptionally well on DSP algorithm and I/O bench- plier, a shifter, and a register file marks (see benchmarks in Table 1 and Table 2) Dual integer ALUs, providing data addressing and pointer Supports low overhead DMA transfers between internal manipulation memory, external memory, memory-mapped peripherals, Integrated I/O includes 14-channel DMA controller, external link ports, other DSPs (multiprocessor), and host port, 4 link ports, SDRAM controller, programmable flag processors pins, 2 timers, and timer expired pin for system integration Eases DSP programming through extremely flexible instruc- 1149.1 IEEE compliant JTAG test access port for on-chip tion set and high-level language-friendly DSP architecture emulation Enables scalable multiprocessing systems with low commu- On-chip arbitration for glueless multiprocessing with up to nications overhead 8 TigerSHARC processors on a bus COMPUTATIONAL BLOCKS PROGRAM SEQUENCER DATA ADDRESS GENERATION INTERNAL MEMORY 6 MEMORY MEMORY MEMORY JTAG PORT SHIFTER PC BTB IRQ INTEGER 32 32 INTEGER M0 M1 M2 JALU KALU ADDR 64K × 32 64K × 32 64K × 32 SDRAM CONTROLLER -

Time Signal Stations 1By Michael A

122 Time Signal Stations 1By Michael A. Lombardi I occasionally talk to people who can’t believe that some radio stations exist solely to transmit accurate time. While they wouldn’t poke fun at the Weather Channel or even a radio station that plays nothing but Garth Brooks records (imagine that), people often make jokes about time signal stations. They’ll ask “Doesn’t the programming get a little boring?” or “How does the announcer stay awake?” There have even been parodies of time signal stations. A recent Internet spoof of WWV contained zingers like “we’ll be back with the time on WWV in just a minute, but first, here’s another minute”. An episode of the animated Power Puff Girls joined in the fun with a skit featuring a TV announcer named Sonny Dial who does promos for upcoming time announcements -- “Welcome to the Time Channel where we give you up-to- the-minute time, twenty-four hours a day. Up next, the current time!” Of course, after the laughter dies down, we all realize the importance of keeping accurate time. We live in the era of Internet FAQs [frequently asked questions], but the most frequently asked question in the real world is still “What time is it?” You might be surprised to learn that time signal stations have been answering this question for more than 100 years, making the transmission of time one of radio’s first applications, and still one of the most important. Today, you can buy inexpensive radio controlled clocks that never need to be set, and some of us wear them on our wrists. -

STANDARD FREQUENCIES and TIME SIGNALS (Question ITU-R 106/7) (1992-1994-1995) Rec

Rec. ITU-R TF.768-2 1 SYSTEMS FOR DISSEMINATION AND COMPARISON RECOMMENDATION ITU-R TF.768-2 STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS (Question ITU-R 106/7) (1992-1994-1995) Rec. ITU-R TF.768-2 The ITU Radiocommunication Assembly, considering a) the continuing need in all parts of the world for readily available standard frequency and time reference signals that are internationally coordinated; b) the advantages offered by radio broadcasts of standard time and frequency signals in terms of wide coverage, ease and reliability of reception, achievable level of accuracy as received, and the wide availability of relatively inexpensive receiving equipment; c) that Article 33 of the Radio Regulations (RR) is considering the coordination of the establishment and operation of services of standard-frequency and time-signal dissemination on a worldwide basis; d) that a number of stations are now regularly emitting standard frequencies and time signals in the bands allocated by this Conference and that additional stations provide similar services using other frequency bands; e) that these services operate in accordance with Recommendation ITU-R TF.460 which establishes the internationally coordinated UTC time system; f) that other broadcasts exist which, although designed primarily for other functions such as navigation or communications, emit highly stabilized carrier frequencies and/or precise time signals that can be very useful in time and frequency applications, recommends 1 that, for applications requiring stable and accurate time and frequency reference signals that are traceable to the internationally coordinated UTC system, serious consideration be given to the use of one or more of the broadcast services listed and described in Annex 1; 2 that administrations responsible for the various broadcast services included in Annex 2 make every effort to update the information given whenever changes occur. -

Vialitehd-EDFA-Datasheet-HRA-X-DS-1

www.vialite.com +44 (0)1793 784389 [email protected] +1 (855) 4-VIALITE [email protected] ® ViaLiteHD – EDFA Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (EDFA) Next generation variable gain EDFA Single or multi-channel EDFA available 8 dB to 36 dB gain variants SNMP and RS232 control Fast start-up time EDFA AGC (Automatic gain control) Bi directional Option Standard 5-year warranty The ViaLiteHD Eribium Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA) is available in either a single channel or multi-channel format depending on where it is utilized in the system. The EDFAs have low noise figures and variable gain ensuring the optimization of link noise figure and performance. They are available as part of a Ka-Band diversity antenna system, ultra-long distance system (up to 600 km) or as a stand-alone product. Options Low noise figure SNMP and RS232 control Fixed gain, auto power control, auto gain control software selectable Low switching time 8 dB, 18 dB, 20 dB, 23 dB, 24 dB, 33 dB or 36 dB gain (other gain variants available) Single channel or multiple channel Applications Formats 1U Chassis Ka-Band diversity rain fade application Fixed satcom earth stations and teleports Related Products Gateway reduction within a satellite footprint 50 km 1550 nm L-Band HTS Government installations 50 Ohm DWDM L-Band HTS Remote monitoring stations >50 km systems Remote oil and gas locations DWDM Multiplexers Remote wind farm locations Optical Switches Optical Delay Lines Popular products HRA-3-0B-8T-AF-D001 – ViaLiteHD EDFA, 24 dB Optical Amplifier, single channel HRA-4-0B-8T-AB-D008 -

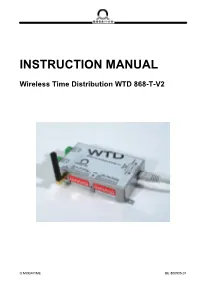

Manual WTD 868T-V2 Transmitter EN Download

INSTRUCTION MANUAL Wireless Time Distribution WTD 868-T-V2 © MOBATIME BE-800905.01 Manufacturer’s Certificate STANDARDS The WTD 868-T-V2 time signal transmitter was developed and produced in accordance with the EU guideline 1999 / 5 / EWG Notes to the Instruction Manual 1. The information contained in this instruction manual can be changed at any time without prior notice. The current version is available for downloading under www.mobatime.com. 2. This instruction manual was compiled with the utmost care to provide all the details regarding the use of this product. However, should you have any queries, or find any errors in the instructions, please contact us. 3. We will not accept any liability for any damages resulting, directly or indirectly, from the use of this instruction manual. 4. Please read these instructions carefully and only use the product when all the instructions on installing and operating have been correctly understood. 5. Installation may only be carried out by qualified personnel. 6. This publication, or any extracts from it, may not be reproduced, stored in a electronic retrieval system, or in any way transmitted. The copyright with all its rights lies with BÜRK MOBATIME GmbH, D-78026 VS-Schwenningen and MOSER-BAER AG, CH–3454 Sumiswald / Switzerland. © MOBATIME 2 / 20 800905.01 Contents 1 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................4 2 Hardware Description .................................................................................................................................5 -

Time and Frequency Users Manual

A 11 10 3 07512T o NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 559 J U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE / National Bureau of Standards Time and Frequency Users' Manual NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress on March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is per- formed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference Materials; and provides -

Synchronizing Time with Dcf77 and Msf60

SYNCHRONIZING TIME WITH DCF77 AND MSF60 In many of the applications that use the H0420 and Starling programmable audio controllers/players, clock synchronization is a requirement. This is especially the case with the H0420, because it lacks a battery backup for its internal real-time clock —hence, when there is a power drop-out (even for less than a second), the H0420 resets to 1 January 1970 at 00:00 hours. Even with a backup battery for the real-time clock, when the device is used outdoor, you may observe the clock on the H0420 or Starling to deviate from the true time. The reason is that the crystals used for timekeeping are calibrated for use at room temperature. The time that the device resets to after power-up, of 1 January 1970 at 00:00 hours, is the "start of the Unix era". This is a commonly used basis for time keeping in operating systems and embedded devices; see the Wikipedia article in the references. For keeping the time of the H0420/Starling accurate, there are two options: get the time from the network (a typical option for the Starling, as it has a network port), or get the time from some other source, such as a radio signal. This latter option is suitable when no network is available at the location, which is common in outdoor use. This article specifically discusses how to pick up the current "time of the day" from DCF77 signal, but also discusses MSF60. A particular advantages of synchronizing on a time signal radio station is that "daylight saving time" is automatically handled. -

How to Build Your Own DCF77 Transmitter

Cheating Time How to build your own DCF77 transmitter Andreas Muller¨ Some infos about the speaker Some infos about DCF77 Spoofing DCF77 Questions/Links 1 Some infos about the speaker 2 Some infos about DCF77 What is DCF77 DCF77 protocol 3 Spoofing DCF77 Motivation? How to spoof the signal Signal generation with ATMega8 Signal generation with soundcard Future of the DCF77 signal Conclusions 4 Questions/Links Andreas Muller¨ Cheating Time Some infos about the speaker Some infos about DCF77 Spoofing DCF77 Questions/Links Some infos about the speaker studying electrical engineering and information technology Chaostreff Aargau other interests: software defined radio hardware misuse and reuse Andreas Muller¨ Cheating Time Some infos about the speaker Some infos about DCF77 What is DCF77 Spoofing DCF77 DCF77 protocol Questions/Links What is DCF77? official german time signal used by many radio controlled clocks for time synchronisation compatible to the swiss HBG signal (at 75kHz) callsign DCF77 (D: germany; C: longwave; F: near Frankfurt) time base is very accurate (atomic clocks used) accurate receiving (<1ms difference) is difficult widely available, due to low frequency Andreas Muller¨ Cheating Time Some infos about the speaker Some infos about DCF77 What is DCF77 Spoofing DCF77 DCF77 protocol Questions/Links DCF77 protocol - signal characteristics continuous wave at 77.5kHz (LF!) amplitude lowered to 25% once per second 100ms for low bit (0) 200ms for high bit (1) power is not lowered when new minute starts 60 bits are transmitted in one minute -

Wireless World

WIRELESS WORLD Over 193,000 copies sold 15th Edition Eddystone EB35 broadcast receiver AM /FM transistorised An excpllent all band receiver, carrat0 be used as a "Hi -Fi" 1MNOFS,FAß tune*'.'=..Powered by 6 U2 torch cells; =ör, with type 924 power BINI supply unit, from AC mains. tlil Eddystone 940 (AC only) communications receiver A connoisseur's instrument combining "Professional" appearance with performance, When you own an Eddystone has a world -wide reputation Communications Receiver with Broadcasting Authorities, "Hams" and SW listeners. you have the broadcasting world at your finger -tips- Eddystone 840C AC/ DC wherever you happen to be- communications receiver Latest version of a on land well - or at sea. The established and popular range reputation these sets have of receivers -equally at home, attained is proof of their ashore or afloat. reliability and excellence and Eddystone EC10 now you can visit a special transistorised Eddystone department at communications receiver Imhofs and see, hear and An enthusiast's receiver at a modest compare all models working price. Embodies features usually only found in side by side on permanent much more expensive designs. demonstration. Powered by 6 U2 torch cells We can arrange despatch to or Type 924 power unit (AC). any part of the world the Eddystone EA12 amateur same day and in the U.K. band receiver delivery is free -backed by For the amateur enthusiast an after sales service for with facilities for acceptance of all modes of transmission. which Imhofs is famous. Will cope with weakest DX Send today for full details. whether AM, CW or SSB.