History of the Monetary Systems and the Public Finances in the Bahamas, 1946-2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 6442-CRG CaribbeanRegion CurrentSituation, Issues and Prospects Public Disclosure Authorized Otober 17,1986 LatinAmerica and the CaribbeanRegional Office FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized U Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the Ubrld Bank Thisdocument has a restricteddistribution and may be usedby recipients onlyin the performanceof theirofficial duties. Its contents may not otherwise bedisclosed without World Bank atithorization. FOR OMCIL UseONLY PREFACE This Reporthas been preparedfor the CaribbeanGroup for Cooperationand EconomicDevelopment (CGCED). Its prime objectiveis to focus attentionon the performance,problems, prospects and the needs of the Caribbeancountries. Part I, Overviewof the CaribbeanEconomies, provides a synopsis of the prcgressand the outlookof the 15 economiesin the region. While the Bank's updatingecononic reports prepared for the CGCED have essentiallya countryfocus, this sectionof the Reportaims at providinga regionalperspective on selectedeconomic policy and sectorissues, particularlyissues in the traditionalexport sectors, in employment, public finance,exchange rate policy,foreign debt, privatesector and state enterprises. Part II examinesthe externalfinancing requirements for each countryin 1986-88. Three points are noteworthy. First,on a per capita basis, these requirementsare quite substantial.Second, in nearlyall countriesthere is now a need for balanceof paymentsor budgetarysupport in additionto externalfinancing of publicsector investment.And -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

National Investment Policy Page 1 of 5

Bahamas National Investment Policy Page 1 of 5 Introduction to The Bahamas Starting 60 miles off the coast of South Florida and stretching as far south as Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, The Bahamas is a coral archipelago of 700 islands, 29 of which are inhabited, and over 2,000 rocks and cays. With a population of some 284,000 people, most of who live on the major islands (New Providence, Grand Bahama, Eleuthera, Abaco, Exuma, Long Island, Inagua, Cat Island, Bimini and Andros), and with an adult literacy rate of 95%, The Bahamas has a capable and adaptable work force. The Bahamas, an English speaking country which gained its independence from Britain on July 10, 1973, is one of the most politically stable countries; a parliamentary democracy has operated without interruption for 275 years. The Bahamas has comprehensive and modern infrastructure, particularly on the two major islands, New Providence and Grand Bahama, where most of the population live. Electricity and water are in abundant supply. Telecommunications services and facilities in The Bahamas are state-of -the-art, with direct international links provided through a 100% digital switching system. The economy of The Bahamas is driven by tourism and international banking and other financial services. Retail and wholesale distributive trades, manufacturing, agriculture and fisheries are the other major sectors of the economy. The Gross Domestic Product (CDP) of The Bahamas exceeds $3 billion, 60% of which comes from tourism related activities. The per capita income of the country is $11,000. The Bahamas is an independent monetary entity. The Bahamian dollar is on par with the U.S. -

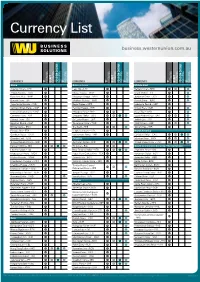

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Appendix 1 Political Forms of the Caribbean Compiled by Yarimar Bonilla, Rutgers University

Appendix 1 Political Forms of the Caribbean Compiled by Yarimar Bonilla, Rutgers University Jurisdiction Political Status and Important Historical Dates Monetary Unit * = on UN list of non-self- governing territories Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Seceded from the Aruba Netherlands Antilles in 1986 with plans for independence, but independence was Aruban florin (AFL) postponed indefinitely in 1994. Constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Former seat of the Antillean guilder N Curacao Netherlands Antilles central government. Became an autonomous country within (ANG) E the kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. T Constituent Country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward H Sint Maarten Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became an autonomous ANG E country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. R L Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Formerly part of the A Bonaire Netherlands Antilles. Became a special municipality within the Kingdom of the US dollar (USD) N Netherlands in 2010. D Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward S Saba Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became a special USD municipality within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010. Special municipality of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Part of the Windward Sint Eustatius Islands territory within the Netherland Antilles until 1983. Became a special USD municipality within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010 Overseas territory of the United Kingdom. Formerly part of the British Leeward Island colonial federation as the colony of Saint Cristopher-Nevis-Anguilla. -

The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 40 Number 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 40, Article 3 Issue 3 1961 The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were Thelma Peters Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Peters, Thelma (1961) "The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 40 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol40/iss3/3 Peters: The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were THE AMERICAN LOYALISTS IN THE BAHAMA ISLANDS: WHO THEY WERE by THELMA PETERS HE AMERICAN LOYALISTS who moved to the Bahama Islands T at the close of the American Revolution were from many places and many walks of life so that classification of them is not easy. Still, some patterns do emerge and suggest a prototype with the following characteristics: a man, either first or second gen- eration from Scotland or England, Presbyterian or Anglican, well- educated, and “bred to accounting.” He was living in the South at the time of the American Revolution, either as a merchant, the employee of a merchant, or as a slave-owning planter. When the war came he served in one of the volunteer provincial armies of the British, usually as an officer. -

The Bahamas Voluntary National Review on the Sustainable Development Goals to the High Level Political Forum of the United Nations Economic and Social Council

The Bahamas Voluntary National Review on the Sustainable Development Goals to the High Level Political Forum of the United Nations Economic and Social Council Government of The Bahamas July 2018 Picture 1: Artwork by students of the Salina Point and the Centreville Primary Schools on the topic – My Vision for The Bahamas in 2040 1 1.0 Table of Contents 1.0 Opening Statement ............................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Highlights ............................................................................................................................. 8 Integration of the SDGs into the National Development Plan .................................................... 8 Institutional Arrangements .......................................................................................................... 9 Leaving No-One -Behind ............................................................................................................ 9 Areas where support is needed for finance, capacity-building, technology, partnerships, etc. 10 3.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 11 4.0 Methodology and process for preparation of the review. .................................................. 13 5.0 Policy and Enabling Environment ..................................................................................... 14 Creating Ownership of the Sustainable Development Goals: National Level -

Pub-6027 a World Bank Country Study

PUB-6027 A WORLD BANK COUNTRY STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized THE BAHAMAS Economic Report Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized H ' .,:'f....( il,.,j } i 1- 11 **f - A WORLD BANK COUNTRY STUDY THE BAHAMAS Economic Report The World Bank Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Copyright ©) 1986 The InternationalBank for Reconstruction and Development/THEWORLD BANK 18I8 H Street, N.W. Washington,D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufacturedin the United States of America First printing June I986 World BankCountry Studies are reports originallyprepared for internal use as part of the continuing analysisby the Bank of the economic and related conditions of its developing membercountries and of its dialogueswith the governments. Some of the reports are publishedinformally with the least possibledelay for the use of governments and the academic, business and financial,and development communities.Thus, the typescripthas not been prepared in accordancewith the proceduresappropriate to fornal printed texts, and the World Bankaccepts no responsibilityfor errors. The publication is suppliedat a token charge to defray part of the cost of manufactureand distribution. The designations employed,the presentationof material,and any maps used in this documentare solely for the convenienceof the reader and do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoeveron the part of the World Bankor is affiliatesconcerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, area, or of its authorities,or concerning the delimitationof its boundariesor national affiliation. The most recent World Bankpublications are describedin the annual spring and fall lists; the continuing research program is described in the annual Abstractsof Current Studies.The latest edition of each is availablefree of charge from the PublicationsSales Unit, Department T, The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W, Washington,D.C. -

Standard Settlement Instructions for Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments

Standard Settlement Instructions For Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments CURRENCY CORRESPONDENT BANK S.W.I.F.T ADDRESS Australian Dollar Westpac Banking Corporation WPACAU2S AUD Sydney, Australia Barbados Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Bridgetown NOCSBBBB BBD Barbados Bermudian Dollar The Bank of N. T. Butterfield & Son Ltd. BNTBBMHM BMD Hamilton, Bermuda Bahamian Dollar Scotiabank (Bahamas) Ltd. NOSCBSNS BSD Nassau, Bahamas Belize Dollar Scotiabank (Belize) Ltd., NOSCBZBS BZD Belize City, Belize Canadian Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCCATT CAD International Banking Division, Toronto Cyprus Pound Bank of Cyprus Public Company Ltd., BCYPCY2N010 CYP Nicosia, Cyrpus Czech Koruna Ceskolovenska Obchodni Banka A.S. CEKOCZPP CZK Prague Danish Krone Nordea Bank Danmark A/S NDEADKKK DKK Copenhagen, Denmark Euro Deutsche Bank AG DEUTDEFF EUR Frankfurt Fiji Dollar Wetspac Banking Corporation WPACFJFX FJD Suva, Fiji Guyana Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Georgetown, NOSCGYGE GYD Guyana Hong Kong Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCHKHH HKD Hong Kong Hungarian Forint MKB Bank ZRT MKKB HU HB HUF Indian Rupee The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCINBB INR Mumbai Indonesian Rupiah Standard Chartered Bank SCBLIDJX IDR Jakarta, Indonesia Israeli Sheqel Bank Hapaolim BM POALILIT ILS Tel Aviv Jamaican Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia Jamaica Ltd. NOSCBSNSKIN JMD Kingston, Jamaica Japanese Yen The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. BOTKJPJT JPY Tokyo Cayman Islands Dollar Scotiabank and Trust (Cayman) Ltd. NOSCKYKX KYD Cayman Islands Malaysian -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

The Commonwealth of the Bahamas National Investment Policy

The Commonwealth Of The Bahamas National Investment Policy Table of Contents MONACO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Honorary Consul of The Bahamas An invitation by the Prime Minister . 3 L’estoril 1/A4 CHICAGO 31 Avenue Princess Grace Bahamas Tourist Office Introduction to The Bahamas . 4 MC 98000, Monaco Principality 8770 W. Bryn Mawr, Suite 1300 Tel.: 377-9330-5150 – Fax: 377-9330-5177 Chicago, IL 60631 Economic Policy . 5 Tel.: (773) 867-8377 - Fax: (773) 867-2910 SWITZERLAND The Investment Environment . 5 Honorary Consul of The Bahamas FLORIDA Schutzengasse 1, Postfach 6075 Bahamas Tourism Office International Financial Centre . 5 CH-8029, Zurich, Switzerland 1200 South Pine Island Road, Suite 770 Investment Incentives . 5 Tel.: 41-226-40-42 – Fax: 41-1-226-40-43 Plantation, FL 33324 Tel.: (954) 236-9292 - Fax: (954) 474-1773 BAHAMAS TOURIST OFFICES Preferential Trade Incentives . 6 CANADA LOS ANGELES Administration of Investment Policy . 6 Bahamas Tourism Office Bahamas Tourism Office 11400 West Olympic Blvd. #200 Establishing a Business in The Bahamas . 6 6725 Airport Road, Suite 202 Los Angeles, CA 90064 Mississauga, Ontario L4V 1V2, Canada Tel.: (310) 312-9544/ (800) 439-6993 Project Proposal Guideline . 6 Tel.: (905) 672-9017 - Fax: (905) 672-2092 Fax: (310) 312-9545 ENGLAND NEW YORK General . 7 Bahamas Tourism Office Bahamas Tourist Office 1. Work Permits Bahamas House 60 East 42nd Street, Suite 1850 New York, NY 10165 10 Chesterfield Street 2. International Owners of Second Homes London, W1J 5JL Tel.: (212) 758-2777 / (800) 823-3136 Fax: (212) 753-6531 Tel.: +44-20-7355-0800 3.