Ending Hunger by 2030 – Policy Actions and Costs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunger Awareness Meal

Hunger Awareness Meal Bring to life the challenges faced by hungry children and families in your community and around the world. CLUB ACTIVITY // Hunger Awareness Meal Food insecurity is an intensely personal children and families around the world. Participants are served a meal representing a randomly selected need affecting nearly one billion people. hunger profile: food secure, acutely undernourished, Promote awareness and education about chronically undernourished, or suffering from hunger in your community with our hidden hunger. Hunger Awareness Meal activity. Hunger relief is a pillar of our service framework. The Hunger Awareness Meal is a 90-minute activity Join Lions and Leos around the world as we unite to that allows Lions, Leos and community members to confront one of the world’s greatest challenges. experience firsthand the nutritional deficits affecting What you’ll need • Dining materials: plates, bowls, utensils, chopsticks, etc. • Non-starchy vegetable, for example: green beans, amaranth, beets, carrots, okra, daikon, peas, salad greens, Swiss chard, asparagus, etc. • Starch/grain, for example: rice, pasta, potato, bread, quinoa, grits, barley, etc. • Protein, for example: meat, tofu, eggs, etc. • Water or other beverage • Hunger Profile Tickets • Hunger Plates Diagram • Introductory remarks (optional) Who you’ll need • Facilitator: introduces the event, provides local context and guides group discussion • Volunteers (event organizing): budget and purchase materials and food • Volunteers (food prep and serving): serve food to participants based on their ticket • Volunteer greeter (optional): hands out hunger profile tickets • Energizers (optional): encourage enthusiasm, participation and reflection among members • Guest speaker (optional): presents additional local context and their anti-hunger work to members during the meal -2- STEP 01: Planning • Introduce the activity to your club and determine the number of participants and the amount of materials and space you will need. -

No. 34 the Right to Adequate Food

UNITED NATIONS The Right to Adequate Food Human Rights Human Rights Fact Sheet No. 34 The Right to Adequate Food Fact Sheet No. 34 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations or the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Material contained in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given and a copy of the publication containing the reprinted material is sent to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Palais des Nations, 8–14 avenue de la Paix, CH–1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ii CONTENTS Page Abbreviations . iv Introduction . 1 I. WHAT IS THE RIGHT TO FOOD? . 2 A. Key aspects of the right to food . 2 B. Common misconceptions about the right to food. 3 C. The link between the right to food and other human rights . 5 D. The right to food in international law. 7 II. HOW DOES THE RIGHT TO FOOD APPLY TO SPECIFIC GROUPS?. 9 A. The rural and urban poor . 10 B. Indigenous peoples. 12 C. Women . 14 D. Children. 16 III. WHAT ARE THE OBLIGATIONS ON STATES AND THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF OTHERS? . 17 A. Three types of obligations. 17 B. Progressive and immediate obligations . 19 C. Obligations with international dimensions . 22 D. The responsibilities of others. -

Virginia Roadmap to End Hunger

Virginia Roadmap to End Hunger Commonwealth of Virginia 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter From the Honorable Governor Ralph S. Northam 3 Introduction 4 Children’s Cabinet Overview 5 Virginia Roadmap to End Hunger 6 Data Story: Hunger in Virginia 7 The Top Ten by 2025 9 Goals and Strategies 10 Expand Child Nutrition Programs Increase Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Women Infant and Children (WIC) Program Increase Nutrition Support for Seniors Grow Access to Local Food for Schools and Families Strengthen Connections Between Food Access Programs and the Healthcare Sector Encourage Food and Agriculture Investments in Food Deserts and Marginalized Communities Amplify Public Awareness of Hunger in Virginia and Support Information Sharing Across Public and Private Sectors Support Community Organizing to Combat Food Insecurity and Hunger Local Hunger Action Coalitions 21 What You Can Do To Help 23 Appendix A 24 Appendix B 25 2 - THE VIRGINIA ROADMAP TO END HUNGER October 20, 2020 Dear Fellow Virginians, As a human crisis, not just a healthcare crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought renewed attention to the broader social determinants of health— food security chief among them. Prior to the onset of COVID-19, Feeding America estimated that nearly 843,000 Virginians were food insecure, including 234,000 children. Current Feeding America projections indicate that an additional 447,000 Virginians will experience food insecurity at some point during the next year because of COVID-19. The Commonwealth has made dramatic progress against hunger in recent years but we know that we can and must do more to fix this solvable problem. -

Hunger Hotspots

Hunger Hotspots FAO-WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity August to November 2021 Outlook HUNGER HOTSPOTS | FAO-WFP EARLY WARNINGS ON ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY AUGUST TO NOVEMBER 2021 OUTLOOK REQUIRED CITATION WFP and FAO. 2021. Hunger Hotspots. FAO-WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity: August to November 2021 outlook. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb6054en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) or the World Food Programme (WFP), concerning the legal or development status of any territory, country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO or WFP in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial uses are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Director, Communications Advocacy and Marketing Division, e-mail: [email protected]. Cover Photo: © WFP/ Fredrik Lerneryd, Immaculée holds beans in her hand in Nyaruguru, Rwanda on 28th of May 2021. -

A Plan of Action to End Hunger in America I

OCTOBER 2015 A Plan of Action to End Hunger in America I. INTRODUCTION In the fall of 2008, then-candidate Barack Obama pledged that as President he would aggressively tackle hunger in America and eliminate childhood hunger. Shortly thereafter, we at the Food Research & Action Center (FRAC) issued a set of recommendations on how to meet that goal (http://frac.org/initiatives/ ending-child-hunger-by-2015/). When Mr. Obama became President, however, he inherited an economy suffering the most drastic downturn in three-quarters of a century. Giant banks and businesses teetered on the brink. Unemployment leapt up and wages fell. Hunger and poverty both rose rapidly. In 2007, 36 million Americans lived in food insecure households. In 2009, that number was 50 million. The President’s pledge met gale-force headwinds. Now, seven years after Mr. Obama made his anti-hunger pledge, the economy is in considerably better shape, though far from fully recovered. While hunger in this rich nation is unacceptable, even in the worst of times, the recovery changes the dynamic, making American hunger both more unacceptable and more solvable. And it is not just the process of recovery that makes it especially timely for the nation to focus again on dramatically reducing hunger and poverty. A range of economic, political, and research developments — briefly summarized in Part II of this paper — tell us that it is time to move aggressively forward. 2 | A Plan of Action to End Hunger in America In Part III, FRAC revisits, builds on, and adapts to current conditions the recommendations it made in early 2009. -

Download GHD-014 Treating Malnutrition in Haiti with RUTF

C ASES IN G LOBAL H EALTH D ELIVERY GHD-014 APRIL 2011 Treating Malnutrition in Haiti with Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Foods In June of 2008, Dr. Joseline Marhone Pierre, the director of the Coordination Unit for the National Food and Nutrition Program of Haiti’s Ministry of Health and Population (MSPP), met with representatives from a consortium of three non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The consortium had completed a six month field trial during which it treated children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) according to a community-based care model with ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF). They were meeting to draft new national protocols for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition using results from the evaluation of the field trial. Contrary to international recommendations, Marhone believed that not only should severely acutely malnourished children be given RUTF, but so should moderately acutely malnourished children. This would mean procuring and delivering RUTF for over 100,000 children. The NGOs maintained that RUTFs were not designed for this use and that Marhone’s plan was not feasible given the rates of moderate and severe acute malnutrition in the country. How could the NGO consortium and Marhone reach an agreement on how to proceed? Overview of Haiti The Republic of Haiti was located on the western third of the Island of Quisqueya, called Hispaniola by the first Spanish settlers who arrived there in 1492. The Spanish ceded the western portion of the island to the French in 1697. With the labor of hundreds of thousands of slaves—estimated at 500,000 at the peak of slavery in the late eighteenth century—the French turned Haiti into the “Jewel of the Antilles,” a leading exporter of coffee, indigo, rum, and sugar. -

Hunger, Poverty, and Health During COVID-19 SPOTLIGHT: Rural Communities

Hunger, Poverty, and Health During COVID-19 SPOTLIGHT: Rural Communities FIGURE 1: Rural Communities Prior to and During COVID-19 Prior to COVID-19 During COVID-19 Hunger Poverty Health Hunger Poverty Health Higher rates Slower job growth COVID-19 deaths Low access to of hunger, after the Great increased in rural health care and Essential especially among Recession has insufficient data areas faster than in greater rate of workers households with contributed to urban areas later in hospital closures children higher poverty the pandemic Source: Food Research & Action Center 2021 © Prior to COVID-19 Hunger: In 2019, rural households were more likely to to telehealth.14 Over the past decade, 133 rural hospitals be food insecure than suburban households (12.1 percent have closed,15 especially in states that have not expanded compared to 10.3 percent among all households, and 16 Medicaid.16 In 2019, 20 percent of rural hospitals were at risk percent among compared to 13.3 percent among households of closing.17 with children).1 Gender disparities in rural areas: There is a lack Poverty: In 2019, rural poverty was 16.1 percent2 compared of diversity in job opportunities for women in rural areas, with 12.6 percent for urban areas.3 Accounting for access and gains to education in wages are lower in rural areas to government assistance programs and for cost of living in compared to urban areas. Single women, with or without calculating the poverty rate appear to reduce disparities in children, are more likely to be in poverty than single women poverty: the 2019 Supplemental Poverty Measure was 11.8 in urban counties. -

How You Can Start and Operate a Soup Kitchen

Mission Possible:How You Can Start and Operate a Soup Kitchen By Irwin S. Stoolmacher, Martin Tuchman & Peter C. Wise Artwork by Susan Darley Mission Possible: How You Can Start and Operate a Soup Kitchen Copyright © 2011 by Irwin Stoolmacher, Martin Tuchman & Peter Wise All rights reserved. Printed in the United States No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The material in this book is not intended as a substitute for advice from attorneys, accountants or other pro- fessionals. Readers should regularly consult their own professional opinions in all matters. Published by Open Door Publications 27 Carla Way Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 www.OpenDoorPublications.com Illustrations by Susan Darley ISBN: 2 More Praise for Mission Possible Almost everyone wants to do something to make a difference. Visionary leaders of the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen (T.A.S.K) have made a huge difference in the lives of their patrons and in those of us who have been privileged to work with them. Mission Possible is about the best practices that have changed peoples’ lives for the better through a soup kitchen. Here’s the model. Make a difference! ~ E. Roy Riley, Bishop, New Jersey Synod, ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) 3 Dedication This book is dedicated to all those who find it necessary to come to a soup kitchen to meet their nutritional needs. 4 Acknowledgements Co-author Martin Tuchman was the conceiver of this project and his foundation, the Tuchman Foundation, is the underwriter of the book. -

Starting Your Own Food Pantry

STARTING YOUR OWN FOOD PANTRY Revised January 2015 SECOND HARVEST INTRODUCTION Second Harvest Food Bank of Middle Tennessee's mission is to feed hungry people and work to solve hunger issues in our community. Second Harvest opened its doors in 1978 with commitment from several community leaders. The purpose of the organization was to provide a central distribution center for companies, groups and individuals who wished to help provide food for hungry people in Middle Tennessee. Modeled after the first food bank established in Phoenix in the mid-1970s, Second Harvest was designed to collect food that would otherwise be wasted, inspect and sort this food and distribute it to soup kitchens, pantries and shelters serving the hungry. During the first year, this process resulted in a total distribution of 160,000 pounds of food to 75 Partner Agencies. Today, Second Harvest distributes tens of millions of pounds each year and counts soup kitchens, food pantries, senior centers, drug & alcohol treatment centers, youth programs and homeless shelters among its Partner Agencies receiving food and working to end hunger. Second Harvest is one of the largest and most comprehensive of over 200 food banks in the Feeding America network. We partner with more than 450 Partner Agencies throughout our 46-county service area in Middle and West Tennessee to feed the hungry. Second Harvest Food Bank of Middle Tennessee 331 Great Circle Road Nashville, TN 37228 Phone: 615-329-3491 Fax: 615-329-3988 secondharvestmidtn.org Starting Food Pantry/Jan. 2015 2 WHAT IS A FOOD PANTRY? A food pantry is a community-based program that collects and safely stores food and household products for free distribution to low-income and needy members of the community. -

Famines and Economics

__/PS tGqS POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1693 Famines and Economics Factorsthat increase vulnerability to famine include poverty, weak social and Martin Ravallion physicalinfrastructure, a weak and unprepared government, and a relativelyclosed political regime. The World Bank Policy Research Department Poverty and Human Resources Division December 1996 | POLIcY RESEARCHWORKING PAPER 1693 Summary findings Defining famine as widespread, usually life-threatening, institutions that work adequately, though not perfectly, hunger or starvation, Ravallion observes that famine has in normal times can fail under unusual stresses. Poor occurred in most parts of the world in the twentieth people can then be highly vulnerable. century, killing many people. But famines are surely Famine can be viewed as a tragic magnification of more avoidable now than ever before. normal market and governmental failures, says Ravallion. Famines defy simple explanations and geographic And the factors that can transform a shock into mass boundaries, says Ravallion. They have happened under starvation seem to be intrinsic features of normal both socialist and capitalist economic systems, and with economies rather than peculiar features of highly and without wars or unusual political or social instability. distorted or badly managed economies. Normally they And economic analysis can help explain famines that in are hidden from view, but they can surfacein a number the past have been explained in terms of often doubtful of ways. single causes, such as a decline in aggregate food Certain elements increase a region's vulnerability to production. famine: Under certain conditions, the threat of mass starvation * Poverty. can emerge from seeminglysmall shocks to an economy, * Weak social and physical infrastructure. -

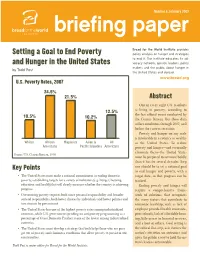

Setting a Goal to End Poverty and Hunger in the United States

Number 6, February 2009 briefing paper Setting a Goal to End Poverty Bread for the World Institute and Hunger in the United States www.bread.org U.S. Poverty Rates, 2007 24.5% 21.5% Abstract One in every eight U.S. residents 12.5% is living in poverty, according to 10.5% the last official count conducted by 10.2% the Census Bureau. But these data reflect conditions through 2007, well before the current recession. Poverty and hunger on any scale is intolerable in a country as wealthy Whites African Hispanics Asian & All as the United States. To reduce Americans Pacific Islanders Americans poverty and hunger-—and eventually eliminate them—the United States Source U.S. Census Bureau, 2008 provides must be prepared to act more boldly policy analysis on hunger and strategies than it has for several decades. Step to end it. The Institute educates its ad- one should be to set a national goal Key Points vocacy network, opinion leaders, policy makersto end and hunger the public and poverty, about hunger with a in • The United States must make a national commitment to ending domestic thetarget United date, States so thatand progressabroad. can be poverty, establishing targets for a variety of indicators (e.g. hunger, housing, tracked. education and health) that will clearly measure whether the country is achieving Ending poverty and hunger will progress. by Todd Post require a comprehensive frame- • Overcoming poverty requires both more personal responsibility and broader work of solutions, that recognizes societal responsibility, both better choices by individuals and better policies and the many factors that contribute to investments by government. -

Zero Hunger Challenge Advisory Notes

TABLE OF CONTENTS ZERO HUNGER CHALLENGE ADVISORY NOTES Pages Introduction 3 - 5 Advisory Notes on . Zero stunted children less than 2 years 6 - 21 . 100% access to adequate food all year round 22 - 30 . All Food Systems are sustainable 31 - 37 . 100% Increase in smallholder productivity 38 - 50 . Zero loos or waste of food 51 - 61 HLTF Participating Agencies 62 INTRODUCTION NOTE TO THE FINAL REPORT BY THE ZERO HUNGER CHALLENGE WORKING GROUPS November 2015 The Zero Hunger Challenge – Advisory notes for action Background The United Nations Secretary-General (SG) launched the Zero Hunger Challenge (ZHC) in June 2012 during the Rio+20 World Conference on Sustainable Development. The Zero Hunger vision calls for a world in which everyone has stable access to adequate food and nourishment all year round; no child less than 2-year-old is stunted; smallholders’ productivity and incomes are at least doubled; all food systems are sustainable; and food loss and waste are eliminated. The Zero Hunger Challenge was launched to inspire a global movement towards a world free from hunger within a generation. Developed in consultation with United Nations agencies, civil society organizations, representatives of the private sector and the Executive Office of the Secretary-General, the Zero Hunger Challenge is based on the Comprehensive Framework for Action (CFA) developed by the High Level Task Force on Global Food and Nutrition Security (HLTF). The Zero Hunger Challenge is organized around five elements, which taken together, will end hunger, eliminate the cruelest forms of malnutrition, contribute to the eradication of rural poverty, and build inclusive and sustainable food and agricultural systems.