143 Caterpillars (Eupithecia Spp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Eupithecia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) 33-39 Deutschen Gesellschaft Für Orthopterologie E.V.; Download

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Articulata - Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Orthopterologie e.V. DGfO Jahr/Year: 1987 Band/Volume: 3_1987 Autor(en)/Author(s): Vojnits Andras M. Artikel/Article: Notes on Eupithecia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) 33-39 Deutschen Gesellschaft für Orthopterologie e.V.; download http://www.dgfo-articulata.de/ Articulata, Bd. Ill, Folge 1, September 1987, Würzburg, ISSN 0171-4090 Notes on Eupithecia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) by A. M. Vojnits Abstract Eupithecia silenicolata zengoeensis Fazekas, 1979 = the nominotypical species. Eupithecia inveterata nom. nov. for £ trita Vojnits, 1977 (secondary homonym, nec E. trita Turati, 1926). The separation as a subspecies of the Central European po pulations of Eupithecia sinuosaria Ev., an actively spreading species, is unrealistic. The paleozoographic analysis of most Eupithecia species rest on insufficient fun- dations. 1. Eupithecia silenicolata zengoeensis Fazekas, 1979 syn. nov. Linnaeana Bel- gica, 11: 406-411, figs. 1-4. Eupithecia silenicolata silenicolata Mabille, 1866 Ann. S. Fr., p. 562. Subspecific name. The Author named the new taxon after highest point in the Mec- sek Mountains, the 682 meters high Mount Zengo, mentioning that this place is the typical location of the subspecies. Following this he stated that the subspecies lives at altitudes between 200-350 m. These areas are entirely different from those of Mount Zengo and its environs, if a taxonomical name is given to a taxon, it should not be misleading under any circumstances. Diagnosis. Of the nine specimens which served as the basis for the description, one is in more or less good condition, one is slightly and the other seven are heavily worn. -

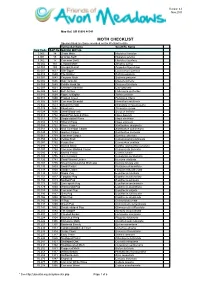

MOTH CHECKLIST Species Listed Are Those Recorded on the Wetland to Date

Version 4.0 Nov 2015 Map Ref: SO 95086 46541 MOTH CHECKLIST Species listed are those recorded on the Wetland to date. Vernacular Name Scientific Name New Code B&F No. MACRO MOTHS 3.005 14 Ghost Moth Hepialus humulae 3.001 15 Orange Swift Hepialus sylvina 3.002 17 Common Swift Hepialus lupulinus 50.002 161 Leopard Moth Zeuzera pyrina 54.008 169 Six-spot Burnet Zygaeba filipendulae 66.007 1637 Oak Eggar Lasiocampa quercus 66.010 1640 The Drinker Euthrix potatoria 68.001 1643 Emperor Moth Saturnia pavonia 65.002 1646 Oak Hook-tip Drepana binaria 65.005 1648 Pebble Hook-tip Drepana falcataria 65.007 1651 Chinese Character Cilix glaucata 65.009 1653 Buff Arches Habrosyne pyritoides 65.010 1654 Figure of Eighty Tethia ocularis 65.015 1660 Frosted Green Polyploca ridens 70.305 1669 Common Emerald Hermithea aestivaria 70.302 1673 Small Emerald Hemistola chrysoprasaria 70.029 1682 Blood-vein Timandra comae 70.024 1690 Small Blood-vein Scopula imitaria 70.013 1702 Small Fan-footed Wave Idaea biselata 70.011 1708 Single-dotted Wave Idaea dimidiata 70.016 1713 Riband Wave Idaea aversata 70.053 1722 Flame Carpet Xanthorhoe designata 70.051 1724 Red Twin-spot Carpet Xanthorhoe spadicearia 70.049 1728 Garden Carpet Xanthorhoe fluctuata 70.061 1738 Common Carpet Epirrhoe alternata 70.059 1742 Yellow Shell Camptogramma bilineata 70.087 1752 Purple Bar Cosmorhoe ocellata 70.093 1758 Barred Straw Eulithis (Gandaritis) pyraliata 70.097 1764 Common Marbled Carpet Chloroclysta truncata 70.085 1765 Barred Yellow Cidaria fulvata 70.100 1776 Green Carpet Colostygia pectinataria 70.126 1781 Small Waved Umber Horisme vitalbata 70.107 1795 November/Autumnal Moth agg Epirrita dilutata agg. -

Scottish Macro-Moth List, 2015

Notes on the Scottish Macro-moth List, 2015 This list aims to include every species of macro-moth reliably recorded in Scotland, with an assessment of its Scottish status, as guidance for observers contributing to the National Moth Recording Scheme (NMRS). It updates and amends the previous lists of 2009, 2011, 2012 & 2014. The requirement for inclusion on this checklist is a minimum of one record that is beyond reasonable doubt. Plausible but unproven species are relegated to an appendix, awaiting confirmation or further records. Unlikely species and known errors are omitted altogether, even if published records exist. Note that inclusion in the Scottish Invertebrate Records Index (SIRI) does not imply credibility. At one time or another, virtually every macro-moth on the British list has been reported from Scotland. Many of these claims are almost certainly misidentifications or other errors, including name confusion. However, because the County Moth Recorder (CMR) has the final say, dubious Scottish records for some unlikely species appear in the NMRS dataset. A modern complication involves the unwitting transportation of moths inside the traps of visiting lepidopterists. Then on the first night of their stay they record a species never seen before or afterwards by the local observers. Various such instances are known or suspected, including three for my own vice-county of Banffshire. Surprising species found in visitors’ traps the first time they are used here should always be regarded with caution. Clerical slips – the wrong scientific name scribbled in a notebook – have long caused confusion. An even greater modern problem involves errors when computerising the data. -

Interesting Species of the Family Geometridae (Lepidoptera) Recently Collected in Serbia, Including Some That Are New to the Country’S Fauna

Acta entomologica serbica, 2018, 23(2): 27-41 UDC 595.768.1(497.11) DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.2547675 INTERESTING SPECIES OF THE FAMILY GEOMETRIDAE (LEPIDOPTERA) RECENTLY COLLECTED IN SERBIA, INCLUDING SOME THAT ARE NEW TO THE COUNTRY’S FAUNA ALEKSANDAR STOJANOVIĆ1, MIROSLAV JOVANOVIĆ1 and ČEDOMIR MARKOVIĆ2 1 Natural History Museum, Njegoševa 51, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry, Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade, Serbia E-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract Seventeen very interesting species were found in studying the fauna of Geometridae of Serbia. Ten of them are new to the fauna of Serbia (Ennomos quercaria, Anticollix sparsata, Colostygia fitzi, Eupithecia absinthiata, E. alliaria, E. assimilate, E. millefoliata, E. semigraphata, Perizoma juracolaria and Trichopteryx polycommata); five are here recorded in Serbia for the second time (Dyscia raunaria, Elophos dilucidaria, Eupithecia ochridata, Perizoma bifaciata and Rhodostrophia discopunctata); and two are recorded for the third time (Nebula nebulata and Perizoma hydrata). Information regarding where and when they were all found is given herein. KEY WORDS: geometrid moths, measuring worms, new record, taxonomy Introduction With more than 23000 species, Geometridae is one of the largest families of the order Lepidoptera (Choi et al., 2017). About 900 species have been found to date in Europe (Hausmann, 2001). Some of them are significant pests in agriculture and forestry (Carter, 1984; Barbour, 1988; Glavendekić, 2002; Pernek et al., 2013). Around 380 species have so far been recorded in Serbia (Dodok, 2006; Djurić & Hric, 2013; Beshkov, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c, 2017a, 2017b; Beshkov & Nahirnić, 2017; Nahirnić & Beshkov, 2016). -

Ecology of Some Lesser-Studied Introduced Ant Species in Hawaiian Forests

Ecology of some lesser-studied introduced ant species in Hawaiian forests Paul D. Krushelnycky Journal of Insect Conservation An international journal devoted to the conservation of insects and related invertebrates ISSN 1366-638X J Insect Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9789-y 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer International Publishing Switzerland. This e- offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Insect Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9789-y ORIGINAL PAPER Ecology of some lesser-studied introduced ant species in Hawaiian forests Paul D. Krushelnycky1 Received: 18 May 2015 / Accepted: 11 July 2015 Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 Abstract Invasive ants can have strong ecological effects suggest that higher densities of these introduced ant species on native arthropods, but most information on this topic could result in similar interactions with arthropods as those comes from studies of a handful of ant species. The eco- of the better-studied invasive ant species. -

Beginner S Guide to Moths of the Midwest Geometers

0LGZHVW5HJLRQ86$ %HJLQQHU V*XLGHWR0RWKVRIWKH0LGZHVW*HRPHWHUV $QJHOOD0RRUHKRXVH ,OOLQRLV1DWXUH3UHVHUYH&RPPLVVLRQ Photos: Angella Moorehouse ([email protected]). Produced by: Angella Moorehouse with the assistance of Alicia Diaz, Field Museum. Identification assistance provided by: multiple sources (inaturalist.org; bugguide.net) )LHOG0XVHXP &&%<1&/LFHQVHGZRUNVDUHIUHHWRXVHVKDUHUHPL[ZLWKDWWULEXWLRQEXWFRPPHUFLDOXVHRIWKHRULJLQDOZRUN LVQRWSHUPLWWHG >ILHOGJXLGHVILHOGPXVHXPRUJ@>@YHUVLRQ $ERXWWKH%(*,11(5¶6027+62)7+(0,':(67*8,'(6 Most photos were taken in west-central and central Illinois; a fewDUH from eastern Iowa and north-central Wisconsin. Nearly all were posted to identification websites: BugGuide.netDQG iNaturalist.org. Identification help was provided by Aaron Hunt, Steve Nanz, John and Jane Balaban, Chris Grinter, Frank Hitchell, Jason Dombroskie, William H. Taft, Jim Wiker,DQGTerry Harrison as well as others contributing to the websites. Attempts were made to obtain expert verifications for all photos to the field identification level, however, there will be errors. Please contact the author with all corrections Additional assistance was provided by longtime Lepidoptera survey partner, Susan Hargrove. The intention of these guides is to provide the means to compare photographs of living specimens of related moths from the Midwest to aid the citizen scientists with identification in the field for Bio Blitz, Moth-ers Day, and other night lighting events. A taxonomic list to all the species featured is provided at the end along with some field identification tips. :(%6,7(63529,',1*,'(17,),&$7,21,1)250$7,21 BugGuide.net LNaturalist.org Mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu Insectsofiowa.org centralillinoisinsects.org/weblog/resources/ :+,&+027+*8,'(7286( The moths were split into 6 groups for the purposes of creating smaller guides focusing on similar features of 1 or more superfamilies. -

Predatory and Parasitic Lepidoptera: Carnivores Living on Plants

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 49(4), 1995, 412-453 PREDATORY AND PARASITIC LEPIDOPTERA: CARNIVORES LIVING ON PLANTS NAOMI E. PIERCE Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138, USA ABSTRACT. Moths and butterflies whose larvae do not feed on plants represent a decided minority slice of lepidopteran diversity, yet offer insights into the ecology and evolution of feeding habits. This paper summarizes the life histories of the known pred atory and parasitic lepidopteran taxa, focusing in detail on current research in the butterfly family Lycaenidae, a group disproportionately rich in aphytophagous feeders and myr mecophilous habits. More than 99 percent of the 160,000 species of Lepidoptera eat plants (Strong et al. 1984, Common 1990). Plant feeding is generally associated with high rates of evolutionary diversification-while only 9 of the 30 extant orders of insects (Kristensen 1991) feed on plants, these orders contain more than half of the total number of insect species (Ehrlich & Raven 1964, Southwood 1973, Mitter et al. 1988, cf. Labandiera & Sepkoski 1993). Phytophagous species are characterized by specialized diets, with fewer than 10 percent having host ranges of more than three plant families (Bernays 1988, 1989), and butterflies being particularly host plant-specific (e.g., Remington & Pease 1955, Remington 1963, Ehrlich & Raven 1964). This kind of life history specialization and its effects on population structure may have contributed to the diversification of phytophages by promoting population subdivision and isolation (Futuyma & Moreno 1988, Thompson 1994). Many studies have identified selective forces giving rise to differences in niche breadth (Berenbaum 1981, Scriber 1983, Rausher 1983, Denno & McClure 1983, Strong et al. -

2017 Scottish Macro Moth List

SCOTTISH MACRO-MOTH LIST, 2017 Vernacular Name Code Taxon UK Status Scottish status Scottish Trend since 1980 Orange Swift 3.001 Triodia sylvina Common Widespread but local stable Common Swift 3.002 Korscheltellus lupulina Common Common S, scarce or absent N stable Map-winged Swift 3.003 Korscheltellus fusconebulosa Local Common stable Gold Swift 3.004 Phymatopus hecta Local Common stable Ghost Moth 3.005 Hepialus humuli Common Common stable Goat Moth 50.001 Cossus cossus Nb Scarce and very local, mainly Highlands stable? Lunar Hornet Moth 52.003 Sesia bembeciformis Common Widespread but overlooked? decline - G. S. Woodpecker predation? Welsh Clearwing 52.005 Synanthedon scoliaeformis RDB Very local in Highlands stable Large Red-belted Clearwing 52.007 Synanthedon culiciformis Nb Widespread but overlooked? stable Red-tipped Clearwing 52.008 Synanthedon formicaeformis Nb Dumfries & Galloway, last seen in 1942 extinct, or overlooked? Currant Clearwing 52.013 Synanthedon tipuliformis Nb SE only? Still present VC82 in 2014 major decline Thrift Clearwing 52.016 Pyropteron muscaeformis Nb SW & NE coasts, very local stable Forester 54.002 Adscita statices Local Very local, W and SW stable? Transparent Burnet 54.004 Zygaena purpuralis Na Very local, west Highlands stable Slender Scotch Burnet 54.005 Zygaena loti RDB Mull only stable Mountain Burnet 54.006 Zygaena exulans RDB Very local, VC92 stable New Forest Burnet 54.007 Zygaena viciae RDB, protected Very local, W coast fluctuates Six-spot Burnet 54.008 Zygaena filipendulae Common Common but mainly coastal range expansion NW, also inland Narrow-bordered Five-spot Burnet 54.009 Zygaena lonicerae Common SE, spreading; VC73; ssp. -

Eupithecia Ogilviata, Geometer Moth

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T97236499A99166874 Scope: Global Language: English Eupithecia ogilviata, Geometer Moth Assessment by: Vieira, V. & Borges, P.A.V. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Vieira, V. & Borges, P.A.V. 2017. Eupithecia ogilviata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T97236499A99166874. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017- 3.RLTS.T97236499A99166874.en Copyright: © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. -

A New Record and Three Little-Known Eupithecia Curtis Species from Turkey (Lepidoptera: Geometridae)

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2017) 41: 583-586 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Short Communication doi:10.3906/zoo-1603-46 A new record and three little-known Eupithecia Curtis species from Turkey (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) Erdem SEVEN* Department of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts, School of Tourism and Hotel Management, Batman University, Batman, Turkey Received: 22.03.2016 Accepted/Published Online: 17.11.2016 Final Version: 23.05.2017 Abstract: In this paper, Eupithecia opistographata Dietze, 1906 is reported as new for the fauna of Turkey, and three rare species (E. brunneata Staudinger, 1900; E. dearmata Dietze, 1904; and E. marasa Wehrli, 1932) are presented as second records on the basis of specimens collected in the mountainous areas of Siirt Province and Şirvan District, southeastern Turkey. The adults and the male genitalia of the species are illustrated. Key words: Eupithecia, Larentiinae, Geometridae, Turkey, fauna The valid genus name Eupithecia was established by work on a doctoral thesis (2011–2013) by using UV light Curtis in 1825 with the type species Phalaena absinthiata traps. Identification was performed by analyzing external Clerck, 1759. This nominate and large genus is in the morphological features of adult moths and the structure family of Geometridae and includes nearly 1400 described of the genital armature of males (Staudinger, 1900; Dietze, species (Scoble, 1999; Mironov and Ratzel, 2012) 1904–1906; Wehrli, 1932; Schütze, 1961; Ratnasingham distributed worldwide. and Hebert, 2007; Mironov and Galsworthy, 2014). Full Adult Eupithecia species are commonly characterized information on localities and dates of captured species by being small in size, cryptically colored grayish, having are given in the results. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

Caterpillars on the Foliage of Conifers in the Northeastern United States 1 Life Cycles and Food Plants

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Coniferous forests are important features of the North American landscape. In the Northeast, balsam fir, spruces, or even pines may dominate in the more northern forests. Southward, conifers still may be prevalent, although the pines become increasingly important. In dry, sandy areas, such as Cape Cod of Massachusetts and the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, hard pines abound in forests composed of relatively small trees. Conifers are classic symbols of survival in harsh environments. Forests of conifers provide not only beautiful scenery, but also livelihood for people. Coniferous trees are a major source of lumber for the building industry. Their wood can be processed to make paper, packing material, wood chips, fence posts, and other products. Certain conifers are cultivated for landscape plants and, of course, Christmas trees. Trees of coniferous forests also supply shelter or food for many species of vertebrates, invertebrates, and even plants. Insects that call these forests home far outnumber other animals and plants. Because coniferous forests tend to be dominated by one to a few species of trees, they are especially susceptible to injury during outbreaks of insects such as the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana, the fall hemlock looper, Lambdina fiscellaria fiscellaria, or the pitch pine looper, Lambdina pellucidaria. Trees that are defoliated by insects suffer reduced growth and sometimes even death. Trees stressed by defoliation, drought, or mechanical injury, are generally more susceptible to attack by wood-boring beetles, diseases, and other organisms. These secondary pests also may kill trees. Stress or tree death can have a negative economic impact upon forest industries.