Chapter 3 Images of Cornwall and Its People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornwall and the Politics of Recognition Written by Simon Thompson

Cornwall and the Politics of Recognition Written by Simon Thompson This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Cornwall and the Politics of Recognition https://www.e-ir.info/2014/10/26/cornwall-and-the-politics-of-recognition/ SIMON THOMPSON, OCT 26 2014 I’m very interested in what’s called the politics of recognition. This phrase is used to describe a wide range of political phenomena in which individuals and groups of various kinds struggle to be recognized for their particular characteristics or identities or achievements. Some groups want to be recognized for being the same as others. So, for example, the American civil rights movement can be understood as a struggle by black Americans to be treated in the same way as all other American citizens. But other groups want recognition of their distinctiveness – of the fact that they are not like others. The recent announcement that Cornish people are to be granted minority status within the UK looks like a case of this kind. The announcement was made by the Council of Europe, a body which describes itself as ‘the continent’s leading human rights organisation’. Founded in 1949, its principal objective is to oversee the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights, which the Council describes as ‘a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law’. Of particular importance to the present case is the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, drawn up in 1995 (http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/html/157.htm). -

Cornishness and Englishness: Nested Identities Or Incompatible Ideologies?

CORNISHNESS AND ENGLISHNESS: NESTED IDENTITIES OR INCOMPATIBLE IDEOLOGIES? Bernard Deacon (International Journal of Regional and Local History 5.2 (2009), pp.9-29) In 2007 I suggested in the pages of this journal that the history of English regional identities may prove to be ‘in practice elusive and insubstantial’.1 Not long after those words were written a history of the north east of England was published by its Centre for Regional History. Pursuing the question of whether the north east was a coherent and self-conscious region over the longue durée, the editors found a ‘very fragile history of an incoherent and barely self-conscious region’ with a sense of regional identity that only really appeared in the second half of the twentieth century.2 If the north east, widely regarded as the most coherent English region, lacks a historical identity then it is likely to be even more illusory in other regions. Although rigorously testing the past existence of a regional discourse and finding it wanting, Green and Pollard’s book also reminds us that history is not just about scientific accounts of the past. They recognise that history itself is ‘an important element in the construction of the region … Memory of the past is deployed, selectively and creatively, as one means of imagining it … We choose the history we want, to show the kind of region we want to be’.3 In the north east that choice has seemingly crystallised around a narrative of industrialization focused on the coalfield and the gradual imposition of a Tyneside hegemony over the centuries following 1650. -

RICHARD W. BARSTOW 26, Tregeseal, St. Just, Near Penzance. Cornwall. England. ORDERING INFORMATION Mail Orders Are Prollipt~Y Fi

RICHARD W. BARSTOW 26, Tregeseal, st. Just, Near Penzance. Cornwall. England. ORDERING INFORMATION Mail orders are prollipt~y filled and despatched on a 7-day examination basis, subject to approval. Immediate refund guaranteed on return of specimens. Please quote the name and the number of the specimen(s) required, and enclose P.O./Cheque with order. No charge is made for postage and packing, except for over seas customers and postage over 50p. We reserve the ~ight to make slight substitutions, if necessary, unless advised to the contrary. Special requests and 'wants lists' are welcome. We hope that we may be of some service to you, and assure you of our best attention at all times. JULY 1973 1. ADAMITE. Ojuela Mine, Mapimi, Mexico. Choice well-formed yellowish green doubly terminated crystals richly encrusting cellular Limonite matrix, with minor Calcite lT in association. 3x2t • £5. 2. ANDRADITE GARNET variety DEMANTOID. Val Malenco,Sondrio, Italy. Well formed sharp apple green crystals richly scattered over Serpentinite. 2txlt". £6. 3. APATITE. Colcerrow Quarry, Luxulyan, Cornwall. Very fine highly modified clear sea green crystals to a tIT in size intergrown and scattered over Pegmatite matrix, with minor Gilbertite mica in association. Six specimens are lT lT being offered varying in size from lxl - lxlt , all show excellent Apatite crYstals, and are taken from an old collection. Prices from £1.50 - £2.50 dependent on quality and size. ~. NATIVE ARSENIC. Grube Sampson, 8'1>. Andreasberg, Harz Mts., Germany. Unusual silvery grey It" botryoidal mass. £~. ANGLESITE. Wheal Penrose, Porthleven, Cornwall. Fine clear glassy crystals to ~ mm. -

Olive Tree Barn PORTLOE • the ROSELAND

OLIVE TREE BARN PORTLOE • THE ROSELAND OLIVE TREE BARN TREVISKEY • PORTLOE • TRURO • CORNWALL • TR2 5PN Country meets coastal; an impressive and versatile barn conversion surrounded by idyllic gardens located just outside the picturesque fishing village of Portloe. Characterful and tasteful barn conversion Peaceful rural setting near the sea Potential annexe Versatile accommodation Master suite 3 further bedrooms Mediterranean style gardens Garage with workshop Distances: Portloe village centre: 0.8 Portscatho: 7.5 St Mawes: 10 Truro: 11 Cornwall Airport, Newquay: 20 (all distances are approximate and in miles) savills.co.uk SAVILLS TRURO 73 Lemon Street, Truro TR1 2PN Tel: 01872 243260 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text Location The Property The hamlet of Treviskey, a few dwellings set in the countryside, is Olive Tree Barn was converted from the old farm buildings of just above the village of Portloe on the Roseland Peninsula, with the Treviskey Farm. The house is filled with great character and charm, Cornish coastline and some of the best beaches in the county within with traditional stone walls hung with wisteria beneath a Delabole slate easy reach. The golden sands of Carne Beach are around three miles roof and eye-catching features in almost every room. The property is away, and Portholland Beach and Caerhays Beach with its castle are surrounded by landscaped gardens, with mature olive trees planted to both nearby. the north with a Mediterranean-inspired courtyard garden to the south. Portloe is a charming fishing village set around the boutique Lugger The kitchen has a high ceiling supported by exposed timbers and a Hotel. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

The Cornish Language in Education in the UK

The Cornish language in education in the UK European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by CORNISH The Cornish language in education in the UK | 2nd Edition | c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Albanian; the Albanian language in education in Italy Aragonese; the Aragonese language in education in Spain and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Asturian; the Asturian language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) of Fryslân. Basque; the Basque language in education in France (2nd ed.) Basque; the Basque language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) Breton; the Breton language in education in France (2nd ed.) Catalan; the Catalan language in education in France Catalan; the Catalan language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Cornish; the Cornish language in education in the UK (2nd ed.) and Language Learning, 2019 Corsican; the Corsican language in education in France (2nd ed.) Croatian; the Croatian language in education in Austria Danish; The Danish language in education in Germany ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Frisian; the Frisian language in education in the Netherlands (4th ed.) 2nd edition Friulian; the Friulian language in education in Italy Gàidhlig; The Gaelic Language in Education in Scotland (2nd ed.) Galician; the Galician language in education in Spain (2nd ed.) The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, German; the German language in education in Alsace, France (2nd ed.) provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European German; the German language in education in Belgium Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

Britishness, What It Is and What It Could Be, Is

COUNTY, NATION, ETHNIC GROUP? THE SHAPING OF THE CORNISH IDENTITY Bernard Deacon If English regionalism is the dog that never barked then English regional history has in recent years been barely able to raise much more than a whimper.1 Regional history in Britain enjoyed its heyday between the late 1970s and late1990s but now looks increasingly threadbare when contrasted with the work of regional geographers. Like geographers, in earlier times regional historians busied themselves with two activities. First, they set out to describe social processes and structures at a regional level. The region, it was claimed, was the most convenient container for studying ‘patterns of historical development across large tracts of the English countryside’ and understanding the interconnections between social, economic, political, demographic and administrative history, enabling the researcher to transcend both the hyper-specialization of ‘national’ historical studies and the parochial and inward-looking gaze of English local history.2 Second, and occurring in parallel, was a search for the best boundaries within which to pursue this multi-disciplinary quest. Although he explicitly rejected the concept of region on the grounds that it was impossible comprehensively to define the term, in many ways the work of Charles Phythian-Adams was the culmination of this process of categorization. Phythian-Adams proposed a series of cultural provinces, supra-county entities based on watersheds and river basins, as broad containers for human activity in the early modern period. Within these, ‘local societies’ linked together communities or localities via networks of kinship and lineage. 3 But regions are not just convenient containers for academic analysis. -

1850 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1850 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes ............................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................................ 46 4. Midsummer Sessions .............................................................................................................................. 54 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................................... 69 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................................... 93 Royal Cornwall Gazette 4 and 11 January 1850 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions were opened on Tuesday, the 1st of January, before the following magistrates:— J. KING LETHBRIDGE, Esq. Chairman; Sir W. L. S. Trelawny, Bart. E. Stephens, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. R. Gully Bennet, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq. T. H. J. Peter, Esq. W. Hext, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. J. S. Enys, Esq. D. P. Hoblyn, Esq. J. Davies Gilbert, Esq. Revds. W. Molesworth, C. Prideaux Brune, Esq. R. G. Grylls, C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq. A. Tatham, W. Moorshead, Esq. T. Phillpotts, W. -

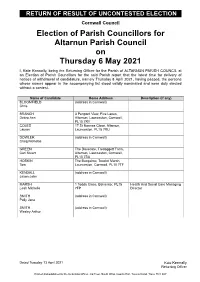

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

A Brief History of the Cornish Language, Its Revival and Its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand University of Wales Trinity Saint David

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 2 Cultural Survival Article 6 12-2-2013 A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand University of Wales Trinity Saint David Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Ferdinand, Siarl (2013) "A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand, University of Wales Trinity Saint David Abstract Despite being dormant during the nineteenth century, the Cornish language has been recently recognised by the British Government as a living regional language after a long period of revival. The first part of this paper discusses the history of traditional Cornish and the reasons for its decline and dismissal. The second part offers an overview of the revival movement since its beginnings in 1904 and analyses the current situation of the language in all possible domains. -

Cornwall. • Wil 1347

COURT DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. • WIL 1347 -Webb John Edward, Newham villa, WhiteGeo.Graham,TheNook,Launcestn Willan Capt. Lawrence Peel R.N. Rose Falmout.h road, Truro White Hy. I Parade passage, Penzance ville, Ale:x:andra road, Penzance Webb The Misses, Polrnan, FoweyR.S.O White H.Rosecadghall,Madron,Penzance Willcock John, Callington R.S.O Webb Richard,8 Harrison terrace, Truro1 White J. 8 Richmond ter. St. Ive~ R.S.O[ Willcocks John R.Alto Vesta vil.Saltash Webb Sydney H. 22Morrab rd.Penzance White James, 7 Stratton terrace; Truro Williams Miss, Portbyhan house, Looe Webber Rev. W. H. Tregony hill, White John, Bolvillan, Looe West, East West, East Looe R.S.O Mevagissey, St. Austell Looe R.S.O WillettWilliam Richard Hany,Stewarts, Webber AlbertEdward, 5 Market strand, White John Thomas, Nevada villa, Hea, Week St. Mary, Stratt.on R.S.O Falmouth Hea Moor R.S.O Willey John, Hartley villas, Godolphin Webber George, 2 Claremont terrace, White Miss, St. David's esplanade, road, Helston Edward street, Truro Fowey R.S.O Willey Joseph, I2 Regent ter. Penzance Webber Miss, Whitehall, Mousehole, White Miss, I Melrose ter. Campfield Willey Richard, Churchtown, Mullion, Penzance hill, Truro Cury Cross Lanes R.S.O - Webber Mrs. Natal villas, Par, Par White Mrs. The Orchard, Alverton, Williams Capt. Brian, Downderry, St. Station R.S. 0 Penzance Germans R. S. 0 Webber Mrs. 5 Strangway's ter. Truro White Mrs. The Walk ho. Launceston Williams Rev.Artbur,Vicarage, Devoran Webber Sml. 7 Gordon terrace, Bodmin White Richard, Trewellard, Pendeen, St. R.S.O Webber Thomas, 6 St.