Open Thesis-Final Copy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT the Future of Sports Programming the Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT The Future of Sports Programming The Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 11 8:15 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Continental Breakfast – The Ritz Carlton Ballroom 9:00 a.m. – 9:15 a.m. Welcome Ahmad Rashad, Summit Host Opening Comments David Stern, NBA Commissioner 9:15 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Panel I: Brand, Content and Community Moderator: Tim Russert (Moderator, Anchor, NBC News) Panelists Leonard Armato (Chairman & CEO, Management Plus Enterprises/DUNK.net) Geraldine Laybourne (Chairman, CEO & Founder, Oxygen Media) Rebecca Lobo (Center/Forward, New York Liberty) Kevin O’Malley (Senior Vice President, Programming, Turner Sports) Al Ramadan (CEO, Quokka Sports) Isiah Thomas (Chairman & CEO, CBA) Description Building a successful brand is at the core of establishing a community of loyal consumers. What types of companies and brands are best positioned for long-term success on the Net? Do new Internet-specific brands have an advantage over established off-line brands staking their claims in cyberspace? Or does the proliferation of Web-specific properties give an edge to established brands that the consumer knows, understands and is comfortable with? Panelists debate the value of an off-line brand in building traffic and equity on-line. 10:15 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Break 10:30 a.m – 11:30 a.m Panel II: The Viewer Experience: 2002, 2005 and Beyond Moderator: Bob Costas (Broadcaster, NBC Sports) Panelists George Blumenthal (Chairman, NTL) Dick Ebersol (Chairman, NBC Sports and Olympics) David Hill (Chairman & CEO, FOX Sports Television Group) Mark Lazarus (President, Turner Sports) Geoff Reiss (SVP of Production & Programming, ESPN Internet Ventures) Bill Squadron (CEO, Sportvision) Description Analysts predict that sports and entertainment programming will benefit most from the advent of large pipe broadband distribution. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born . -

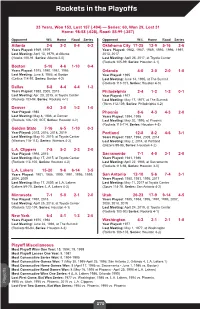

Rockets in the Playoffs

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A. -

Racism in the Ron Artest Fight

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4zr6d8wt Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 13(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Williams, Jeffrey A. Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/LR8131027082 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" by Jeffrey A. Williams* "There's a reason. But I don't think anybody ought to be surprised, folks. I really don't think anybody ought to be surprised. This is the hip-hop culture on parade. This is gang behavior on parade minus the guns. That's what the culture of the NBA has become." - Rush Limbaugh1 "Do you really want to go there? Do I have to? .... I think it's fair to say that the NBA was the first sport that was widely viewed as a black sport. And whatever the numbers ultimately are for the other sports, the NBA will always be treated a certain way because of that. Our players are so visible that if they have Afros or cornrows or tattoos- white or black-our consumers pick it up. So, I think there are al- ways some elements of race involved that affect judgments about the NBA." - NBA Commissioner David Stern2 * B.A. in History & Religion, Columbia University, 2002, J.D., Columbia Law School, 2005. The author is currently an associate in the Manhattan office of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. The views reflected herein are entirely those of the author alone. -

Michael Jordan and Baseball

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 10-6-1993 Michael Jordan and Baseball Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Michael Jordan and Baseball" (1993). On Sport and Society. 329. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/329 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR ARETE October 6, 1993 It was the opening of the American League Championship Series; the first time the Chicago White Sox had been in the playoffs for ten years. Michael Jordan threw out the ceremonial first pitch. It should have been a great night for the White Sox, Chicago's neglected team. Instead, in the seventh inning word spread across America and across the stadium that the man who threw out the first pitch was about to retire from the Chicago Bulls and the NBA. As the White Sox were getting blasted by the Blue Jays, word spread, a pall came over the stadium, and once again the White Sox were the other story in Chicago. On Wednesday morning Michael Jordan made it official. -

Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Us-C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 From "Ping-Pong Diplomacy" to "Hoop Diplomacy": Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of U.S.-China Relations Pu Haozhou Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION FROM “PING-PONG DIPLOMACY” TO “HOOP DIPLOMACY”: YAO MING, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS By PU HAOZHOU A Thesis submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Pu Haozhou defended this thesis on June 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Giardina Professor Directing Thesis Joshua Newman Committee Member Jeffrey James Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Michael Giardina, my thesis committee chair and advisor, for his advice, encouragement and insights throughout my work on the thesis. I particularly appreciate his endless inspiration on expanding my vision and understanding on the globalization of sports. Dr. Giardina is one of the most knowledgeable individuals I’ve ever seen and a passionate teacher, a prominent scholar and a true mentor. I also would like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Joshua Newman, for his incisive feedback and suggestions, and Dr. Jeffrey James, who brought me into our program and set the role model to me as a preeminent scholar. -

H Oya B Asketball G Eorgetow N Staff Team R Eview Tradition R Ecords O Pponents G U Athletics M Edia

9 2 2006-07 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL HoyaHoya BasketballBasketball GGeorgetowneorgetown StaffStaff TeamTeam ReviewReview Tradition Records Opponents GU Athletics Media Tradition Staff Staff Georgetown Basketball Hoya Team Team Review Tradition Media Athletics GU Opponents Records 2006-072 0 0 6 - 0 7 GEORGETOWNG E O R G E T O W N MEN’SM E N ’ S BASKETBALLB A S K E T B A L L 9 3 Basketball Hoya Georgetown Staff Hoya Tradition In its fi rst 100 years, the Georgetown Basketball program has been highlighted by rich tradition... Historical records show us the accomplishments of future Congressman Henry Hyde and his team in the 1940s. Professional achievement tells us of the academic rigor and athletic pursuits of the 1960s that helped shape Paul Tagliabue, former Commissioner of the NFL. Trophies, awards and championships are evidence of the success John Thompson Jr. compiled in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. It is the total combination: academic and athletic excellence, focus, dedication and hard work instilled in Hoya teams throughout the last century that built men who would not only conquer the basketball court, but serve their communities. This is the tradition of Georgetown University and its basketball program. Team Team Review Review Tradition 1942 Buddy O’Grady, Al Lujack and Don Records Opponents Athletics GU Media 1907 1919 Bill Martin graduate and are selected by the Bornheimer Georgetown beats Virginia, 22-11, in the Led by Fred Fees and Andrew Zazzali, National Basketball Association. They are fi rst intercollegiate basketball game in the Hilltop basketball team compiles the fi rst of 51 Hoyas to play in the NBA. -

The Tax Ramifications of Catching Home Run Baseballs

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 59 Issue 1 Article 8 2008 Note of the Year: The Tax Ramifications of Catching Home Run Baseballs Michael Halper Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Halper, Note of the Year: The Tax Ramifications of Catching Home Run Baseballs, 59 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 191 (2008) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol59/iss1/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 2008 NOTE OF THE YEAR THE TAx RAMIFICATIONS OF CATCHING HOME RUN BASEBALLS 1. THE RECENT HISTORY OF HOME RuN BASEBALLS The summer of 1998 marked the rebirth of America's pastime, Major League Baseball, following several years of stunted growth caused by 1994's player strike. The resurgence is attributed in large part to the general public's fascination with the summer-long chase of Roger Maris's single-season record of sixty-one home runs. The St. Louis Cardinals' Mark McGwire and his Popeye-esque forearms led the charge, blasting twenty-seven home runs before the end of May, putting him on pace to hit more than eighty home runs by season's end.' In June, the Chicago Cubs' "Slammin"' Sammy Sosa smashed twenty home runs to set the all-time single-month home run record and position himself just four home runs behind McGwire, thirty-seven to thirty-three, beginning the season-long race to sixty-one.2 On August 10, Sosa finally caught McGwire, hitting his forty-fifth and forty-sixth home runs. -

A Closer Look at How One Asian Is a Representative for an Entire Race

Linplexity: A Closer Look at How One Asian is a Representative for an Entire Race Ryan Kitaro Kwai-ming Hata, San Francisco State University, USA The Asian Conference on Media & Mass Communication 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract Asians specifically in America, negotiate with the depictions of microaggressions rooted in racism in everyday life. According to Derald W. Sue et al. (2007), “racial microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily, verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communication hostile, derogatory; or negative racial slights and insults towards people of color” (p. 271). Common microaggressions imposed on Asian Americans in the media are their portrayal as perpetual foreigners, “Yellow Perils,” or the model minority. The image of Jeremy Lin as the “model minority,” low-keyed, passive athlete is seldom problematized and often encouraged by mainstream media. However, Asian scholars, sports commentators, filmmakers and journalists have noticed mainstream media unconsciously or uncritically directs microaggressions at Jeremy Lin through the model minority myth. Hence, the tension in these portrayals of Asians through Lin on an individual level as the model minority constitutes and extends the microaggression. Using Critical Race Theory and “symbolic microaggressions,” my research will apply content and critical discourse analysis to provide a clearer picture of Lin to deconstruct Asian stereotypes, microaggressions, and colorblindness. I will be comparing and contrasting non-Asian media perceptions of Jeremy Lin with the Linsanity documentary (directed and produced by Asian Americans). Can Jeremy Lin’s portrayal in mainstream media as a model minority be oppressive and empowering at the same time? Finally, I will seek to address the larger impact of this work on Jeremy Lin in terms of how the media represents Asians both in United States and globally. -

Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’S Cold War

Death at the Wing Episode 6: Drazen Petrovic and Basketball’s Cold War ⧫ ⧫ ⧫ Back in 1988, the USA Men’s Basketball team did something they almost never did... ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: The United States found themselves in a position in the last seven minutes of this game of having to score on almost every possession and they could not. After winning 9 of the last 10 Olympics they competed in, they lost. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: But there’s no time, really, for even a miracle now. And the Soviets are already celebrating. The USA suddenly found itself wearing bronze. It did not go over well. And so, as the dust settled, they decided to do what America does best: get better through hard work, inch by inch, grinding it out… I’m kidding. No, we did the real American thing. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: What may well be the best basketball team ever assembled… ...which is throwing lots of money at something to make even more money. And so, for the next Olympics, they formed a super squad of sorts. No more amateurs. It was time to bend the rules a little bit and bring in the pros. And, of course, bring in Reebok to sponsor it. ARCHIVAL ANNOUNCER: And now, the United States of America. This was the Dream Team. Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan. This wasn’t about winning gold. This was about buying the whole fucking gold mine. Shock and awe. 1 But in Barcelona in 1992, one player in all of the Olympics didn’t get the memo... or fax.