The Jacobite Lairds of Gask

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Office Perth Directory

/X v., SANDEMAN PUBLIC LIBRARY, PERTH REFERENCE DEPARTMENT Tfeis bcok , which is Ihe properfy of Ihe Sanderrears Pu blic Librarj-z.nzust be returma lo its Appropriate pla.ce or2 fhe shelves, or, if received fronz Ihe issue coui2i:er, ha^ndzd back to the Libnar-ia>f2-ir2- charge. ITMUSTNOTBE REMOVED FROM THE REFEREKJCE DEPARTMENT, urzless prior pern2issioj2 has beeri giverz by the Librariar2 irz charge. READERS ARE REQUESTED TO TAKE CARE OF LIBRARY BOOKS. Wnh^^g or dr<5.wir29 wUb per? or pej2cil 0J2 &r2y p&rt of 2^ book, or tuminQ dowrz Ihe jeav^es.or culling or rrzidil&iirzQ then2, will belrcdded <a£ serious ddm- akge.Trkcmg is not perrailied, a.r2d readers faking r»ies ir?usf f20t use irzk or place the paper orz which they are vriti/22 ou Ihe book. Conversa-lion in ihe Reference Depajrtn2er2f is ir ri tat ir2p fo olher readers arzd is r2oI permitted. Class: lsi^\W l'??^ Accession No.(^ 1^.% Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.arGhive.org/details/postofficeperthd1872prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 187 2, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PI;T]^LTSHER J3Y D. WOOD. PRICE I WO SHlrltlN'Gs' AND SIXPENCE. CONTENTS. Page 1. Public Offices, ... ... ... ... i 2. Municipal Lists, ... ... ... ... 3 3. County Lists, ... ... ... ... 6 4. Judicial Lists, ... ... ... ... 10 5. Commercial Lists, ... .. ... ... 15 6. Public Conveyances, ... ... ... 19 7. Ecclesiastical Lists, ... ... ... 21 8. Literary AND Educational Lists, .. -

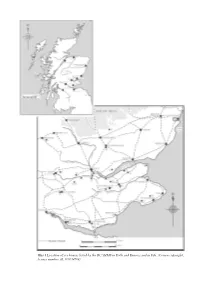

Illus 1 Location of Ice Houses Listed by the RCAHMS in Perth and Kinross and in Fife

Illus 1 Location of ice houses listed by the RCAHMS in Perth and Kinross and in Fife. (Crown copyright, licence number AL 100034704) Three Perthshire ice houses: selected results of a desk-based assessment and a programme of field investigations Adrian Cox Introduction of building an ice house. Its compiler, Philip Miller, stressed the importance of a dry situation for the build- This paper presents some of the results of a desk-based ing, noting that moisture was prejudicial to the storage assessment of the nature, level of recording and condi- of ice. A raised position, to facilitate drainage, was also tion of surviving ice-houses in Perthshire and Fife, desirable. along with selected results of a small programme of The fishing industry was the largest consumer of ice field investigations undertaken with a view to highlight- in Britain, and the last user of natural ice. The earliest ing site management and conservation issues. The re- large-scale use was in Scotland, where ice collected sults of investigations of three ice houses in Perthshire from lochs was used in the late 18th and 19th centuries are presented in depth here, and discussed in the light for packing salmon for transportation. By around 1820, of an overview of the historical background to ice ice was becoming routinely used in the salmon trade house construction and use. Both the desk-based as- across Britain. sessment and subsequent field investigations were spon- During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the sored by Historic Scotland. wealth of landowners increased rapidly, leading to in- Although important features in the 17th- to 19th- creased demand for ice in summer to cool drinks and century landscape, many ice houses across Scotland make exotic desserts. -

Note: Page Numbers in Italic Refer to Figures

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03402-0 — Women of Fortune Linda Levy Peck Index More Information Index Note: Page numbers in italic refer to Figures Abbott, Edward , Frances Bennet , – Abbott, George Grace Bennet , Abbott, Sir Maurice and marriage of daughter Abbott, Robert, scrivener and banker , and marriages of Simon Bennet’s daughters Abbott family , abduction (of heiresses), fear of , Arlington, Isabella, Countess of Abington, Great and Little, Cambridgeshire Arran, Earl of (younger son of Duke of , – Ormond) , foreclosure by Western family , Arthur, Sir Daniel Abington House , Arundel, Alatheia Talbot, Countess of Admiralty Court, and Concord claim – aspirations “Against the Taking Away of Women” and architecture ( statute) George Jocelyn’s , –, Ailesbury, Diana Bruce, Countess of , John Bennet’s , Ailesbury, Robert Bruce, st Earl of , of parish gentry Ailesbury, Thomas Bruce, nd Earl of Astell, Mary and Frances, Countess of Salisbury , , Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, Barnes’strial , at on Grace Bennet , , Albemarle, nd Duke of Bacon, Francis Alfreton, Derbyshire , , Bagott, Sir Walter, Bt Andrewes, Lancelot, Bishop Bahia de Todos os Santos, Brazil Andrewes, Thomas, merchant Baines, Dr. Thomas Andrewes, Thomas, page Baker, Fr. Anglo-Dutch War (–) , Bancroft, John, Archbishop of Canterbury Anne, Queen , Bank of England Appleby School shares in apprenticeship banking Bennets in Mercers’ Company early forms Charles Gresley private , gentlemen apprentices –, , – see also moneylending -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Experience Europe with Local Connection and Support

EXPERIENCE EUROPE WITH LOCAL CONNECTION AND SUPPORT NEW UNTOURS IN PORTUGAL: Porto & the Douro, Sintra & Lisbon 2019 • #UNTOURS • VOL. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS UNTOURS & VENTURES ICELAND PORTUGAL Ventures Cruises ......................................25 NEW, Sintra .....................................................6 SWITZERLAND NEW, Porto ..................................................... 7 Heartland & Oberland ..................... 26-27 SPAIN GERMANY Barcelona ........................................................8 The Rhine ..................................................28 Andalusia .........................................................9 The Castle .................................................29 ITALY Rhine & Danube River Cruises ............. 30 Tuscany ......................................................10 HOLLAND Umbria ....................................................... 11 Leiden ............................................................ 31 Venice ........................................................ 12 AUSTRIA Florence .................................................... 13 Salzburg .....................................................32 Rome..........................................................14 Vienna ........................................................33 Amalfi Coast ............................................. 15 EASTERN EUROPE FRANCE Prague ........................................................34 Provence ...................................................16 Budapest ...................................................35 -

The Significance of Anya Seton's Historical Fiction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction. Lindsey Marie Okoroafo (Jesnek) University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public History Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Secondary Education Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Okoroafo (Jesnek), Lindsey Marie, "Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2676. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2676 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional -

Leslie's Directory for Perth and Perthshire

»!'* <I> f^? fI? ffi tfe tI» rl? <Iy g> ^I> tf> <& €l3 tf? <I> fp <fa y^* <Ti* ti> <I^ tt> <& <I> tf» *fe jl^a ^ ^^ <^ <ft ^ <^ ^^^ 9* *S PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION including KINROSS-SHIRE These books form part of a local collection permanently available in the Perthshire Room. They are not available for home reading. In some cases extra copies are available in the lending stock of the Perth and Kinross District Libraries. fic^<fac|3g|jci»^cpcia<pci><pgp<I>gpcpcx»q»€pcg<I»4>^^ cf>' 3 ^8 6 8 2 5 TAMES M'NICOLL, BOOT AND SHOE MAKER, 10 ST. JOHN STREET, TID "XT' "IIP rri "tur .ADIES' GOODS IN SILK, SATIN, KID, AND MOROCCO. lENT.'S HUNTING, SHOOTING, WALKING, I DRESS, IN KID AND PATENT. Of the Newest and most Fashionable Makes, £ THE SCOTTISH WIDOWS' FUNDS AND REVENUE. The Accumulated Funds exceed £9,200,000 The Annual Revenue exceeds 1,100,000 The Largest Funds and Revenue possessed by any Life Assurance Institution in the United Kingdom. THE PROFITS are ascertained Septennially and divided among the Members in Bonus Addi- tions to their Policies, computed in the corrfpoundioxva.^ i.e., on Original Sums Assured and previous Bonus Additions attaching to the Policy—an inter- mediate Bonus being also added to Claims between Divisions ; thus, practically an ANNUAL DIVISION OF PROFITS is made among the Policyholders, founded on the ample basis of seven years' operations, yielding to each his equitable share down to date of death, in respect of every Premium paid since the date of the policy. -

Inverness Burgh Directory

m. M •^.^nr> ..«/ 'V.y 1. Vv y XHK &Feat Scoteh Wineey Manufactured exjaressly for JOHN FORBKS, Itiverness, in New Stripes and Checks, also in White and all Colours, IS the: idkal. fabric for Ladies' Blouses, Children's Dresses, Gent's Shirts and Pyjamas, and every kind of Day, Night and Underwear, ENDLESS IN WEAR AND POSITIVELY UNSHRINKABLE. 31 inches wide, 1/9 per yard. New Exclusive Weaves. All Fast Colours. Pattern Bunches Free on application to JOHN FORBES Hig^li Street Sc Ingrlis Street INVERNESS. "ESTATE DUTIES.'* Distinctive System OF Assurance. I4OW Premiums. Lo^v Expenses. SCOTTISH PROVIDENT INSXmJTION. AccuHinlated^iFunds jeiceecl £13,750,000. Aberdeen Branch : 166 UNION STREET Inspector of Agencies (Northern District :) WILLIAM FARQUHARSON. rJAMES D. MACKIE. Local Secretaries j^j^^^j^j) TENNANT. AGENTS IN INVERNESS; Messrs ANDERSON & SHAW, W.S, Messrs JAMES ROSS & BOYD, Solicitors, DAVID ROSS, Solicitor, 63 Church Street, Head Office—No. 6 St. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH : ® Dortaem $ls$urancc ConqKini^ l2ead Offices flbeMeen S London FIRE. LIFE. ACCIDENT. Accumulated Funds, £6,782,900 FIRK BRAKCH Large Keserves, Prompt and equitable settlement of Losses. Surveys made and rates quoted free of charge. I^IFK BRAKCH The "with profits" section has many features attractive to Assurants, Amongst these are THE STRONG RESERVES.—Very stringent Eeserves, on a 2| per cent, basis, have been set aside. THE LOW EXPENSES.—The expenditure is restricted to 10 per cent, of the premiums. ALL PROFITS TO ASSURED.— Policy-holders receive the entire profits. They thus obtain the advantages of a Mutual Society, and in addition the further security afforded by a Proprietary Ofiice. -

Love Letters Between Lady Susan Hay and Lord James Ramsay 1835

LOVE LETTERS BETWEEN LADY SUSAN HAY AND LORD JAMES RAMSAY 1835 Edited by Elizabeth Olson with an introduction by Fran Woodrow in association with The John Gray Centre, Haddington I II Contents Acknowledgements iv Editing v Maps vi Family Trees viii Illustrations xvi Introduction xxx Letters 1 Appendix 102 Further Reading 103 III Acknowledgements he editor and the EERC are grateful to East Lothian Council Archives Tand Ludovic Broun-Lindsay for permission to reproduce copies of the correspondence. Thanks are due in particular to Fran Woodrow of the John Gray Centre not only for providing the editor with electronic copies of the original letters and generously supplying transcriptions she had previously made of some of them, but also for writing the introduction. IV Editing he letters have been presented in a standardised format. Headers provide Tthe name of the sender and of the recipient, and a number by which each letter can be identified. The salutations and valedictions have been reproduced as they appear in the originals, but the dates when the letters were sent have been standardised and placed immediately after the headers. Due to the time it took for letters from England to reach Scotland, Lord James Ramsay had already sent Lady Susan Hay three before she joined the correspondence. This time lapse, and the fact that thereafter they started writing to each other on a more or less daily basis, makes it impossible to arrange the letters sensibly in order of reply. They have instead been arranged chronologically, with the number of the reply (where it can be identified) added to the notes appended to each letter. -

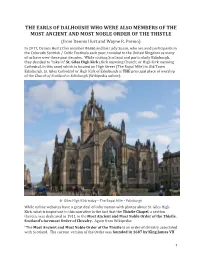

THE EARLS of DALHOUSIE WHO WERE ALSO MEMBERS of the MOST ANCIENT and MOST NOBLE ORDER of the THISTLE (From Dennis Hurt and Wayne R

THE EARLS OF DALHOUSIE WHO WERE ALSO MEMBERS OF THE MOST ANCIENT AND MOST NOBLE ORDER OF THE THISTLE (from Dennis Hurt and Wayne R. Premo) In 2017, Dennis Hurt (Clan member #636) and his Lady Susan, who are avid participants in the Colorado Scottish / Celtic Festivals each year, traveled to the United Kingdom as many of us have over these past decades. While visiting Scotland and particularly Edinburgh, they decided to “take in” St. Giles High Kirk (Kirk meaning Church; or High Kirk meaning Cathedral, in this case) which is located on High Street (The Royal Mile) in Old Town Edinburgh. St. Giles Cathedral or High Kirk of Edinburgh is THE principal place of worship of the Church of Scotland in Edinburgh (Wikipedia online). St. Giles High Kirk today – The Royal Mile – Edinburgh While online websites have a great deal of information with photos about St. Giles High Kirk, what is important to this narrative is the fact that the Thistle Chapel, a section therein, was dedicated in 1911 to the Most AnCient anD Most Noble OrDer oF the Thistle, SCotlanD’s Foremost OrDer oF Chivalry. Again from Wikipedia: “The Most AnCient anD Most Noble OrDer oF the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII 1 of ScotlanD (James II of England and Ireland) who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order. The Order consists of the Sovereign and sixteen Knights and Ladies, as well as certain "extra" knights (members of the British Royal Family and foreign monarchs). -

The London Gazette Jjubltebt) Bj> Registered As a Newspaper **• for Table of Contents See Last Page FRIDAY, 15 APRIL, 1949

£umb. 38587 1891 The London Gazette JJubltebt) bj> Registered as a newspaper **• For Table of Contents see last page FRIDAY, 15 APRIL, 1949 TENDERS FOR TREASURY BILLS. His Majesty has also been pleased to approve 1. The Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's of the retention of the title of "Honourable" by Treasury hereby give notice that Tenders will be Lionel William Ryan, Esq., who has served as a received at the Chief Cashier's Office, at the Bank Member of the (Legislative Council of the State of of England, on Friday, the 22nd April, *1949, at New South Wales for a continuous period of not 1 p.m. for Treasury Bills to be issued under the less than ten years. Treasury Bills Act, 1877, the National Debt Act, 1889, and the National Loans Act, 1939, to the amount of £170,000,000. 2. The Bills will be in amounts of £5,000, £10,000, The Church House, Westminster, S.W.I. £25,000, £50,000 or £100,000. They will be dated at the option of the tenderer on any business day The KING has .been pleased to give directions for from Monday, the 25th April, 1949, to Saturday, the appointment of Mr. V. R. Bairamian (Chief the 30th April, 1949, inclusive, and will be payable Registrar, Supreme Court, Nigeria) to be a Puisne at three months after date. Judge of His Majesty's Supreme Court, Nigeria. 3. The Bills will be issued and paid at the Bank of England. 4. Each Tender must be for an amount not less than £50,000 and must specify the date on which The Scottish Home Department, the Bills required are to be dated, and the net Edinburgh, 1.