Other Chapters 1. Introduction 2. Grading Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Climbing Gym Industry and Oslo Klatresenter As

Norwegian School of Economics Bergen, Spring 2021 Valuation of Oslo Klatresenter AS A fundamental analysis of a Norwegian climbing gym company Kristoffer Arne Adolfsen Supervisor: Tommy Stamland Master thesis, Economics and Business Administration, Financial Economics NORWEGIAN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS This thesis was written as a part of the Master of Science in Economics and Business Administration at NHH. Please note that neither the institution nor the examiners are responsible − through the approval of this thesis − for the theories and methods used, or results and conclusions drawn in this work. 2 Abstract The main goal of this master thesis is to estimate the intrinsic value of one share in Oslo Klatresenter AS as of the 2nd of May 2021. The fundamental valuation technique of adjusted present value was selected as the preferred valuation method. In addition, a relative valuation was performed to supplement the primary fundamental valuation. This thesis found that the climbing gym market in Oslo is likely to enjoy a significant growth rate in the coming years, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in sales volume of 6,76% from 2019 to 2033. From there, the market growth rate is assumed to have reached a steady-state of 3,50%. The period, however, starts with a reduced market size in 2020 and an expected low growth rate from 2020 to 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on this and an assumed new competing climbing gym opening at the beginning of 2026, OKS AS revenue is forecasted to grow with a CAGR of 4,60% from 2019 to 2033. -

Smith Rock (All Dates Are Month/Day/Year)

Smith Rock (all dates are month/day/year) 5.2 Arrowpoint, Northwest Corner (5.2 Trad) comments: This is the obvious way up the Arrowpoint. Although extremely short, it rewards one with a rare Smith summit experience, which is nice after climbing one of the multi-pitch routes on Smith Rock group. Unfortunately, the Arrowhead is not the true summit of the Smith Rock group. gear: 3 or 4 cams to #3 Camalot ascents: 06/25/2005 lead (approached via Sky Ridge) 03/23/2009 lead (approached via Sky Ridge, PB seconded) 5.5 New Route Left of Purple Headed Warrior (5.5 ? Bolts) comments: Squeeze job with so-so climbing. ascents: 11/6/2016 lead Bits and Pieces (1st Pitch) (5.5 Bolts) comments: Very easy fun route on huge knobs. ascents: 06/17/2001 lead My Little Pony (5.5 Bolts) comments: To the right of the Adventurous Pillar there are four bolted routes. This is the fourth one from the left. ascents: 05/09/2004 lead Night Flight (5.5 Bolts) comments: Route 22 in the Dihedrals section of smithrock.com, to the left of Left Slab Crack. Nice and easy lead. ascents: 03/16/2001 lead 03/30/2001 2nd (continued on Easy Reader 2nd pitch) North Slab Crack (5.5X or TR) comments: Horrible route. ascents: 09/16/2000 (TR) Pack Animal (to Headless Horseman belay) (5.5 Trad) comments: Easy and short trad lead. ascents: 02/08/2004 lead Spiderman Variation (1st pitch) (5.5 Trad) comments: Nice, but not as good as the 1st pitch of Spiderman proper. -

Multi-Pitch Trad Course

MULTI-PITCH TRAD COURSE This course is designed to teach the skills required to complete climb multi-pitch trad routes. Students will be given time and education to safely and efficiently lead multi-pitch climbs. Skills Covered Building of 3-point gear anchors Belaying a follower from the top with an auto-blocking device Swapping leads Being efficient on climbs including proper rope management Basic rescue techniques Understanding route selection Graduation Criteria Safely lead 1 multi-pitch trad route Prerequisites Single-pitch trad course or equivalent o Ability to lead on trad gear up to 5.6 o Ability to rappel safely o Ability to build a top-rope anchor on bolts o Basic skills to climb cracks Summary of Activities 1 evening kickoff session 2 evenings for skills review 2 weekend days of outdoor multi-pitch mock leading on trad gear 2 weekend days of outdoor multi-pitch leading on trad gear Student Gear List *Please DO NOT purchase gear until after our Kick Off Session (#17 & #18 are above what is required for the single-pitch course) 1. Climbing helmet 2. Rock climbing shoes 3. Harness 4. 1 personal anchor (Metolius) + locking carabiner 5. 6 single alpine slings 6. 2 double alpine slings 7. 1 triple alpine sling 8. 18 standard-sized non-locking carabiners (2 per sling) 9. 6 locking carabiners (in addition to the one in #4) 10. One set of standard-sized cams One cam each matching the following Black Diamond sizes: .3, .4, .5, .75, 1, 2, 3 11. 7 carabiners – one for each cam Do not need to be full sized Getting carabiners that match the color of your cams will be helpful 12. -

Rätikon (...And Frankenjura!)

Rätikon (...and Frankenjura!) Imperial College expedition 5-18th August 2015 Contents 1 Expedition summary 3 2 Aims 3 3 Logistics 5 3.1 Transport and Accommodation . 5 3.2 Equipment . 6 3.3 Food............................................. 7 3.4 Weather . 7 4 The team 7 4.1 Expedition members . 7 4.1.1 Amar Nanda (21): 2nd year medical student . 7 4.1.2 Elliot White (21): Climbing route-setter . 9 4.2 Training and preparation . 9 5 Trip diary 9 5.1 Gruobenfieber (7+/6c) . 10 5.2 Miss Partnun (9-/7b+) . 13 5.3 Grüscher Älpi . 16 5.4 Frankenjura . 20 6 Finances 21 7 Legacy 27 8 Acknowledgements 28 2 1 EXPEDITION SUMMARY For any climber looking to do challenging, alpine style multipitch, pilgrimage to the Rätikon mountain range is a must. Situated at the borderlands between Austria, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland, the region is saturated with world class climbing. Routes are famous for being exposed and isolated, with large run outs and long walk-ins. After dreaming of tip-toeing up the massive wall of the Kirchlispitzen for the past four years, in summer 2015, with the support of Imperial college Exploration board we finally set off for that soaring limestone face. The Rätikon was everything we hoped for and more. Crazily technical climbing on stunning rock terrified and thrilled us in equal measure. However, heartbreakingly, we never made it to the Kirchlispitzen. Our van had major problems just 500m before reaching the base camp area for the climbs. Unable to go on and unable to leave the van blocking the road we were forced to retreat back down to the valley, and, after much deliberation we fled to the flatland of the Frankenjura forest in Germany, climbing there for the rest of the trip. -

2014 AMGA SPI Manual

AMERICAN MOUNTAIN GUIDES ASSOCIATION AMGA Single Pitch Instructor 2014 Program Manual American Mountain Guides Association P.O. Box 1739 Boulder, CO 80306 Phone: 303-271-0984 Fax: 303-271-1377 www.amga.com 1 AMGA Single Pitch Instructor Program © American Mountain Guides Association Participation Statement The American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) recognizes that climbing and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Clients in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions. The AMGA provides training and assessment courses and associated literature to help leaders manage these risks and to enable new clients to have positive experiences while learning about their responsibilities. Introduction and how to use this Manual This handbook contains information for candidates and AMGA licensed SPI Providers privately offering AMGA SPI Programs. Operational frameworks and guidelines are provided which ensure that continuity is maintained from program to program and between instructors and examiners. Continuity provides a uniform standard for clients who are taught, coached, and examined by a variety of instructors and examiners over a period of years. Continuity also assists in ensuring the program presents a professional image to clients and outside observers, and it eases the workload of organizing, preparing, and operating courses. Audience Candidates on single pitch instructor courses. This manual was written to help candidates prepare for and complete the AMGA Single Pitch Instructors certification course. AMGA Members: AMGA members may find this a helpful resource for conducting programs in the field. This manual will supplement their previous training and certification. -

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan PALMS TO PINES STATE SCENIC HIGHWAY CALIFORNIA STATE ROUTES 243 AND 74 June 2012 This document was produced by USDA Forest Service Recreation Solutions Enterprise Team with support from the Federal Highway Administration and in partnership with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region, the Bureau of Land Management, the California Department of Transportation, California State University, Chico Research Foundation and many local partners. The USDA, the BLM, FHWA and State of California are equal opportunity providers and employers. In accordance with Federal law, U.S. Department of Agriculture policy and U.S. Department of Interior policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720- 5964 (voice and TDD). Table of Contents Chapter 1 – The Palms to Pines Scenic Byway .........................................................................1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Benefits of National Scenic Byway Designation .......................................................................... 2 Corridor Management Planning ................................................................................................. -

LECTURE #5 Glacier Travel & Crevasse Rescue Pt

Basic Rock & Glacier Climbing Course 2018 – Tacoma Mountaineers LECTURE #5 Glacier Travel & Crevasse Rescue Pt. 2 Lecture 5 Topics Glacier Travel Crevasse Rescue What to Expect on Glacier Climbs Field Trip Leader Q & A (Field Trips 5, 6P, 6/7) Assigned Reading (complete prior to Lecture #5) The Freedom of the Hills, 9th edition Glacier Travel & Crevasse Rescue Chapter 18 Mountain Geology Chapter 26 The Cycle of Snow Chapter 27 Basic Rock & Glacier Climbing Course Manual All Lecture #5 Material GLACIER TRAVEL & CREVASSE RESCUE OVERVIEW Glacier travel employs all the techniques used in snow travel with one major addition, navigating crevasses. Crevasses are vertical ice trenches in the snow, which are very hazardous and ready to trap the careless climber. They tend to stay hidden until later in the season when the snow melts and collapses into the crevasse. If the snow coverage is thick and strong you will likely walk right over the crevasse and never know it. Sometimes a visible crevasse will have a snow bridge that you can cross if it’s strong enough, but the real hazard is the crevasse with just a weak thin covering of snow that will not support a climber’s weight. It is not always the lead climber that breaks through, it may be the second or third or even the next rope team. You never know. That’s why you ALWAYS ROPE-UP WHEN TRAVELING ON A GLACIER and keep the rope fully extended. It’s ideal to have three climbers per rope and at least two teams, so if you have to perform a rescue, it is much faster and easier. -

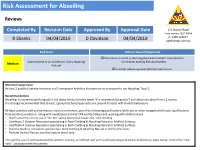

Risk Assessment for Abseiling

Risk Assessment for Abseiling Reviews Completed By Revision Date Approved By Approval Date 171 Nojoor Road Twin waters QLD 4564 P: 1300 122677 R Shanks 04/04/2019 D Davidson 04/04/2019 Apexcamps.com.au Risk level Action required/approval Document controls in planning documents and/or complete this Some chance or an incident or injury requiring Curriculum Activity Risk Assessment. Medium first aid Consider obtaining parental/carer permission. Minimum supervision At least 1 qualified Activity Instructor and 1 competent Activities Assistant are to be present to run Abseiling. Total 2. Recommendations Abseiling is recommended for grade 5 and above for the 6 metre tower. It is recommended grades 7 and above can abseil from 12 metres . It is strongly recommended that at least 1 group teachers/supervisors are present to assist with student behaviours All Apex activities staff and contractors hold at a minimum ,one of the following qualifications /skills sets or other recognised skill sets/ qualifications from another jurisdiction, along with mandatory First Aid/ CPR and QLD Blue Card, working with children check. • Staff trained for correct use of “Gri Gri” safety device that lowers the rock climbing . • Certificate 3 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Certificate 4 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Diploma Outdoor recreation specialising is Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Perform Vertical Rescue also Haul system abseil only. Through the use of well maintained equipment, training, accredited staff and sound operating procedures and policies, Apex Camps control the “real risks” associated with this activity In assessing the level of risk, considerations such as the likelihood of an incident happening in combination with the seriousness of a consequence are used to gauge the overall risk level for an activity. -

Korona VI, South Face, Georgian Direct

AAC Publications Korona VI, South Face, Georgian Direct Kyrgyzstan, Ala Archa National Park After staying a few days in the Ratsek Hut, Giorgi Tepnadze and I hiked up to the Korona Hut, a demotivating place due to its poor condition and interior design. We first went to the foot of Free Korea Peak to inspect a route we planned to try on the north face, and then set up camp below Korona’s less frequently climbed Sixth Tower (one of the highest Korona towers at 4,860m), at the head of the Ak-Sai Glacier. We began our climb on July 9, on a rightward slanting ramp to the right of known routes on the south face. After some moderate mixed climbing, we headed up a direct line for four difficult pitches: dry tooling with and without crampons; aid climbing up to A2+; free climbing with big (yet safe) fall potential, and then a final traverse left to cross a wide snow shelf and couloir. On the next pitch, starting up a steep rock wall, we spotted pitons and rappel slings; the rock pitches involved steep free climbing to 5c. The ninth pitch was wet, and above this we constructed a bivouac under a steep rock barrier, after several hours of dedicated effort. Next day was Giorgi’s turn to lead. The weather was horrible, and Giorgi had to dance the vertical in plastic boots. However, we tried our best to free as much as we could. Surprisingly, we found pitons on two pitches, before we made a leftward traverse, and more as we aided a wet chimney. -

Rock Climbing Fundamentals Has Been Crafted Exclusively For

Disclaimer Rock climbing is an inherently dangerous activity; severe injury or death can occur. The content in this eBook is not a substitute to learning from a professional. Moja Outdoors, Inc. and Pacific Edge Climbing Gym may not be held responsible for any injury or death that might occur upon reading this material. Copyright © 2016 Moja Outdoors, Inc. You are free to share this PDF. Unless credited otherwise, photographs are property of Michael Lim. Other images are from online sources that allow for commercial use with attribution provided. 2 About Words: Sander DiAngelis Images: Michael Lim, @murkytimes This copy of Rock Climbing Fundamentals has been crafted exclusively for: Pacific Edge Climbing Gym Santa Cruz, California 3 Table of Contents 1. A Brief History of Climbing 2. Styles of Climbing 3. An Overview of Climbing Gear 4. Introduction to Common Climbing Holds 5. Basic Technique for New Climbers 6. Belaying Fundamentals 7. Climbing Grades, Explained 8. General Tips and Advice for New Climbers 9. Your Responsibility as a Climber 10.A Simplified Climbing Glossary 11.Useful Bonus Materials More topics at mojagear.com/content 4 Michael Lim 5 A Brief History of Climbing Prior to the evolution of modern rock climbing, the most daring ambitions revolved around peak-bagging in alpine terrain. The concept of climbing a rock face, not necessarily reaching the top of the mountain, was a foreign concept that seemed trivial by comparison. However, by the late 1800s, rock climbing began to evolve into its very own sport. There are 3 areas credited as the birthplace of rock climbing: 1. -

Waypoint Namibia

Majka enjoys a perfect crack on Southern Crossing. Big wall Waypoint Namibia What makes a climb impassable? I’m 215-meters up a first ascent of a granite crack climb in the heart of Namibia, and all I have to hold onto is a bush. Lots of bushes. Trees, too. In order to get where I’m going - the summit - I need what’s behind the bushes, the thing these bushes are choking, the thing that I have travelled 15,400 kilometers by plane, truck, and foot for: a perfect crack. amibia is not known for its climbing, which is exactly why I wanted to go there. It’s better known as Africa’s newest Nindependent country, the source of the continent’s largest stores of uranium and diamonds, the Namib Desert, the Skeleton Coast, and its tribal peoples. Previously known as Southwest Africa, this former German colony and South African protectorate holds some of the most coveted, and least visited, natural sites in Africa. In the middle of all of these lies Spitzkoppe, a 500-meter granite plug with over eighty established climbs. When I learned about Spitzkoppe in December 2007, I automatically started wondering what else might be possible to climb in Namibia. I pick unlikely climbing destinations because I want to learn what happens on the margins of adventure. War, apartheid, and remoteness have all combined to keep many of Namibia’s vertical landscapes relatively unexplored. When I found an out-of-focus photo of a 1,000-meter granite prow with a mud Himba hut in the foreground, I knew I had found my objective. -

Is Retaining Students in the Early Grades Self-Defeating?

Center on Children and Families at BROOKINGS August 2012 CCF Brief # 49 Is Retaining Students in the Early Grades Self-Defeating? Martin R. West | 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.797.6000 | fax 202.697.6004 | brookings edu Acknowledgements The Center on Children and Families thanks the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, the Piton Foundation, and the Birth to Five Policy Alliance for their support in conceiving and funding this policy brief and associated outreach activities. Summary Whether a child is a proficient reader by the third grade is an important indicator of their future academic success. Indeed, substantial evidence indicates that unless students establish basic reading skills by that time, the rest of their education will be an uphill struggle. This evidence has spurred efforts to ensure that all students receive high-quality reading instruction in and even before the early grades. It has also raised the uncomfortable question of how to respond when those efforts fail to occur or prove unsuccessful: Should students who have not acquired a basic level of reading proficiency by grade three be promoted along with their peers? Or should they be retained and provided with intensive interventions before moving on to the next grade? Several states and school districts have recently enacted policies requiring that students who do not demonstrate basic reading proficiency at the end of third grade be retained and provided with remedial services. Similar policies are under debate in state legislatures around the nation. Although these policies aim to provide incentives for educators and parents to ensure that students meet performance expectations, they can also be expected to increase the incidence of retention in the early grades.