UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Download World Class Streets

World Class Streets: Remaking New York City’s Public Realm CONTENTS 2 Letter from the Mayor 3 Letter from Commissioner 6 World Class Streets: Remaking New York City‘s Public Realm 14 How Do People Use New York Streets? 36 New York City‘s World Class Streets Program 53 Acknowledgments 54 Additional Resources and Contacts 1 New York City Department of Transportation LETTER from ThE MAYOR Dear Friends: In 2007, our Administration launched PlaNYC, our Finally, it’s no accident that New York City’s merchant long term plan to create a greener, greater New York. communities focus heavily on streetscape quality One of the challenges PlaNYC poses to city agencies is through their local Business Improvement Districts, to “re-imagine the City’s public realm”—to develop an which we have worked hard to expand and support. For urban environment that transforms our streets and storefront businesses, welcoming, attractive streets can squares into more people-friendly places. spell the difference between growth and just getting by. With 6,000 miles of City streets under its Today, our Administration is dramatically extending the management, the Department of Transportation is on streetscape improvements that many organizations have the front line of this effort—and it is succeeding in been able to create locally. spectacular fashion. New York has the most famous streets in the world. Through new initiatives such as Broadway Boulevard, Now, we’re working to make them the most attractive the Public Plaza Program, Coordinated Street Furniture, streets in the world for walking and cycling—and that and Summer Streets, we are finding creative new ways other great New York sport, people-watching. -

1 State of New York City of Yonkers 2 ------X 3 Minutes of the City of Yonkers Planning Board 4 May 13, 2020 - 5:37 P.M

Page 1 1 STATE OF NEW YORK CITY OF YONKERS 2 -------------------------------------------------X 3 MINUTES OF THE CITY OF YONKERS PLANNING BOARD 4 MAY 13, 2020 - 5:37 P.M. 5 at 6 VIRTUAL HEARING 7 DUE TO COVID-19 PANDEMIC 8 --------------------------------------------------X 9 10 B E F O R E: 11 ROMAN KOZICKY, CHAIRMAN MACKENZIE FORSBERG, MEMBER 12 GENE JOHNSON, MEMBER ADELIA LANDI, MEMBER 13 JOHN LARKIN, MEMBER 14 15 P R E S E N T: 16 LEE ELLMAN, PLANNING DIRECTOR 17 CHRISTINE CARNEY, PLANNING DEPARTMENT ALAIN NATCHEV, ASSISTANT CORP. COUNSEL 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Diamond Reporting 877.624.3287 A Veritext Company www.veritext.com Proceedings Page 2 1 I N D E X 2 ITEM: PAGE: 3 2. Steve Accinelli - 70 Salisbury Road (Held) 5 4 3. Janet Giris - 555 Tuckahoe Road (Held) 6 5 6 4. Tom Abillama - 1969 Central Park Avenue 6 7 5. Janet Giris - Alexander, Babcock, Water Grant 56 8 9 6. Andrew Romano - 2 Lamatine Terrace 13 10 7. Referral from Yonkers City Council Amendment 17 11 To Chapter 43 Article XV (AHO) 12 8. David Steinmetz - 189 South Broadway 31 13 14 9. Janet Giris - 21 Scarsdale Road 60 15 10. James Wilson - 679 Warburton Avenue 76 16 17 11. Steven Accinelli - Prospect, B Vista, Hawthorne 76 (Held) 18 19 12. Stephen Grosso - 220-236 Warburton Avenue 85 20 13. Correspondence N/A 21 22 23 24 25 Diamond Reporting 877.624.3287 A Veritext Company www.veritext.com Proceedings Page 3 1 THE CHAIRMAN: Okay, this is a regular 2 meeting of the City of Yonkers Planning Board pursuant 3 to Governor Cuomo's Executive Order 202.1. -

10 Astor Place 10 Astor Place ™ 10 Astor Place

™ 10 ASTOR PLACE 10 ASTOR PLACE ™ 10 ASTOR PLACE 10 ASTOR PLACE Built in 1876 by the architect Griffith Thomas in a neo-Grecian style, 10 Astor Place was originally a factory and printing office. This building stands 7 stories tall and encompasses 156,000 square feet featuring a recently renovated building lobby. The building's loft-like spaces feature high ceilings and large windows offering an abundance of natural light. Located on Astor Place and in the Noho district, the building is close to the buzz of the Village with NYU and Washington Square Park just moments away. Retail, coffee shops and restaurants offer a variety of amenities along with quick, easy access to the R, W and 6 trains. ™ 10 ASTOR PLACE THE BUILDING Location Southwest corner of Astor Place and Lafayette Street Year Built 1876 Renovations Lobby - 2016; Elevators - 2016; Windows - 2018 Building Size 156,000 SF Floors 7, 1 below-grade ™ 10 ASTOR PLACE TYPICAL FLOOR PLAN 19,400 RSF ™ 10 ASTOR PLACE BUILDING SPECIFICATIONS Location Southwest corner of Astor Place Windows Double-insulated, operable and Lafayette Street Fire & Mini Class E fire alarm system with Year Built 1910 Life Safety Systems command station, defibrillator, building fully sprinklered Architect Griffith Thomas Security Access 24/7 attended lobby, key card access, 156,000 SF Building Size closed-circuit cameras Floors 7, 1 below-grade Building Hours 24/7 with guard Construction Concrete, steel & wood Telecom Providers Spectrum, Verizon, Pilot Renovations Lobby - 2016; elevators - 2016; Cleaning Common -

Emergency Response Incidents

Emergency Response Incidents Incident Type Location Borough Utility-Water Main 136-17 72 Avenue Queens Structural-Sidewalk Collapse 927 Broadway Manhattan Utility-Other Manhattan Administration-Other Seagirt Blvd & Beach 9 Street Queens Law Enforcement-Other Brooklyn Utility-Water Main 2-17 54 Avenue Queens Fire-2nd Alarm 238 East 24 Street Manhattan Utility-Water Main 7th Avenue & West 27 Street Manhattan Fire-10-76 (Commercial High Rise Fire) 130 East 57 Street Manhattan Structural-Crane Brooklyn Fire-2nd Alarm 24 Charles Street Manhattan Fire-3rd Alarm 581 3 ave new york Structural-Collapse 55 Thompson St Manhattan Utility-Other Hylan Blvd & Arbutus Avenue Staten Island Fire-2nd Alarm 53-09 Beach Channel Drive Far Rockaway Fire-1st Alarm 151 West 100 Street Manhattan Fire-2nd Alarm 1747 West 6 Street Brooklyn Structural-Crane Brooklyn Structural-Crane 225 Park Avenue South Manhattan Utility-Gas Low Pressure Noble Avenue & Watson Avenue Bronx Page 1 of 478 09/30/2021 Emergency Response Incidents Creation Date Closed Date Latitude Longitude 01/16/2017 01:13:38 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 12:13:31 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/22/2016 08:53:17 AM 11/14/2016 03:53:54 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 05:35:28 PM 12/02/2016 04:40:13 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 11/25/2016 04:06:09 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 12/03/2016 04:17:30 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/26/2016 05:45:43 AM 11/18/2016 01:12:51 PM 12/14/2016 10:26:17 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 -

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(Es)

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(es) Location Remains UN Plaza Hotel (Park Hyatt) 1981 1 UN Plaza Manhattan N Reader's Digest 1981 28 West 23rd Street Manhattan Y NYC Dept of General Services 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Summit Hotel 1981 51 & LEX Manhattan N Schieffelin and Company 1981 2 Park Avenue Manhattan Y Ernst and Company 1981 1 Battery Park Plaza Manhattan Y Reeves Brothers, Inc. 1981 104 W 40th Street Manhattan Y Alpine Hotel 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Brooks Brothers 1982 1120 Ave of Amer. Manhattan Y Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Sanwa Bank 1982 220 Park Avenue Manhattan Y City Miday Club 1982 140 Broadway Manhattan Y Royal Business Machines 1982 Manhattan Manhattan * Billboard Publications 1982 1515 Broadway Manhattan Y U.N. Development Program 1982 1 United Nations Plaza Manhattan N Population Council 1982 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza Manhattan Y Park Lane Hotel 1983 36 Central Park South Manhattan Y U.S. Trust Company 1983 770 Broadway Manhattan Y Ford Foundation 1983 320 43rd Street Manhattan Y The Shoreham 1983 33 W 52nd Street Manhattan Y MacMillen & Co 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Solomon R Gugenheim 1983 1071 5th Avenue Manhattan * Museum American Bell (ATTIS) 1983 1 Penn Plaza, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y NYC Office of Prosecution 1983 80 Center Street, 6th Floor Manhattan Y Mc Hugh, Leonard & O'Connor 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Keene Corporation 1983 757 3rd Avenue Manhattan Y Melhado, Flynn & Assocs. 1983 530 5th Avenue Manhattan Y Argentine Consulate 1983 12 W 56th Street Manhattan Y Carol Management 1983 122 E42nd St Manhattan Y Chemical Bank 1983 277 Park Avenue, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y Merrill Lynch 1983 55 Water Street, Floors 36 & 37 Manhattan Y WNET Channel 13 1983 356 W 58th Street Manhattan Y Hotel President (Best Western) 1983 234 W 48th Street Manhattan Y First Boston Corp 1983 5 World Trade Center Manhattan Y Ruffa & Hanover, P.C. -

Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture James

The Communal Legitimacy of Collective Violence: Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture by James Peter Phelan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©James Phelan, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the influences that New York City‘s Irish-Americans had on the violence, politics, and underground subcultures of the antebellum era. During the Great Famine era of the Irish Diaspora, Irish-Americans in Five Points, New York City, formed strong community bonds, traditions, and a spirit of resistance as an amalgamation of rural Irish and urban American influences. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Irish immigrants and their descendants combined community traditions with concepts of American individualism and upward mobility to become an important part of the antebellum era‘s ―Shirtless Democracy‖ movement. The proto-gang political clubs formed during this era became so powerful that by the late 1850s, clashes with Know Nothing and Republican forces, particularly over New York‘s Police force, resulted in extreme outbursts of violence in June and July, 1857. By tracking the Five Points Irish from famine to riot, this thesis as whole illuminates how communal violence and the riots of 1857 may be understood, moralised, and even legitimised given the community and culture unique to Five Points in the antebellum era. iii Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

Meeting Notice

5415 VOLUME CXLVIII NUMBER 160 THURSDAY, AUGUST 19, 2021 Price: $4.00 Health and Mental Hygiene ���������������������� 5448 Homeless Services �������������������������������������� 5449 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Human Resources Administration ������������ 5449 Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City . .5449 BILL DE BLASIO Mayor PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Finance and Operations . 5449 Borough President - Manhattan . 5415 Parks and Recreation . 5449 LISETTE CAMILO Business Integrity Commission . 5415 Revenue and Concessions . 5449 Commissioner, Department of Citywide City Planning Commission ������������������������ 5416 Police Department �������������������������������������� 5450 Administrative Services Civic Engagement Commission . 5445 Management and Budget . 5450 Board of Education Retirement System ����� 5446 New York City Police Pension Fund ���������� 5450 JANAE C. FERREIRA Housing Authority �������������������������������������� 5446 Procurement ���������������������������������������������� 5450 Editor, The City Record Office of Labor Relations ���������������������������� 5446 Records and Information Services ������������ 5450 Administration. 5450 Published Monday through Friday except legal PROPERTY DISPOSITION holidays by the New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services . 5446 CONTRACT AWARD HEARINGS Citywide Administrative Services under Authority of Section 1066 of the New York City Charter. Housing Preservation and Development . 5446 Information Technology and Telecommunications . 5450 Subscription -

Arrive a Tourist. Leave a Local

TOURS ARRIVE A TOURIST. LEAVE A LOCAL. www.OnBoardTours.com Call 1-877-U-TOUR-NY Today! NY See It All! The NY See It All! tour is New York’s best tour value. It’s the only comprehensive guided tour of shuttle with you at each stop. Only the NY See It All! Tour combines a bus tour and short walks to see attractions with a boat cruise in New York Harbor.Like all of the NYPS tours, our NY See It All! Our guides hop o the shuttle with you at every major attraction, including: START AT: Times Square * Federal Hall * World Trade Ctr. Site * Madison Square Park * NY Stock Exchange * Statue of Liberty * Wall Street (viewed from S. I. Ferry) * St. Paul’s Chapel * Central Park * Trinity Church * Flatiron Building * World Financial Ctr. * Bowling Green Bull * South Street Seaport * Empire State Building (lunch cost not included) * Strawberry Fields * Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick's Cathedral In addition, you will see the following attractions along the way: (we don’t stop at these) * Ellis Island * Woolworth Building * Central Park Zoo * Met Life Building * Trump Tower * Brooklyn Bridge * Plaza Hotel * Verrazano-Narrows Bridge * City Hall * Hudson River * Washington Square Park * East River * New York Public Library * FAO Schwarz * Greenwich Village * Chrysler Building * SOHO/Tribeca NY See The Lights! Bright lights, Big City. Enjoy The Big Apple aglow in all its splendor. The NY See The Lights! tour shows you the greatest city in the world at night. Cross over the Manhattan Bridge and visit Brooklyn and the Fulton Ferry Landing for the lights of New York City from across the East river. -

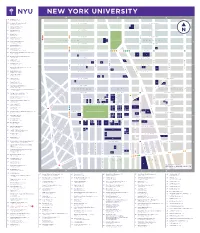

Nyu-Downloadable-Campus-Map.Pdf

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY 64 404 Fitness (B-2) 404 Lafayette Street 55 Academic Resource Center (B-2) W. 18TH STREET E. 18TH STREET 18 Washington Place 83 Admissions Office (C-3) 1 383 Lafayette Street 27 Africa House (B-2) W. 17TH STREET E. 17TH STREET 44 Washington Mews 18 Alumni Hall (C-2) 33 3rd Avenue PLACE IRVING W. 16TH STREET E. 16TH STREET 62 Alumni Relations (B-2) 2 M 25 West 4th Street 3 CHELSEA 2 UNION SQUARE GRAMERCY 59 Arthur L Carter Hall (B-2) 10 Washington Place W. 15TH STREET E. 15TH STREET 19 Barney Building (C-2) 34 Stuyvesant Street 3 75 Bobst Library (B-3) M 70 Washington Square South W. 14TH STREET E. 14TH STREET 62 Bonomi Family NYU Admissions Center (B-2) PATH 27 West 4th Street 5 6 4 50 Bookstore and Computer Store (B-2) 726 Broadway W. 13TH STREET E. 13TH STREET THIRD AVENUE FIRST AVENUE FIRST 16 Brittany Hall (B-2) SIXTH AVENUE FIFTH AVENUE UNIVERSITY PLACE AVENUE SECOND 55 East 10th Street 9 7 8 15 Bronfman Center (B-2) 7 East 10th Street W. 12TH STREET E. 12TH STREET BROADWAY Broome Street Residence (not on map) 10 FOURTH AVE 12 400 Broome Street 13 11 40 Brown Building (B-2) W. 11TH STREET E. 11TH STREET 29 Washington Place 32 Cantor Film Center (B-2) 36 East 8th Street 14 15 16 46 Card Center (B-2) W. 10TH STREET E. 10TH STREET 7 Washington Place 17 2 Carlyle Court (B-1) 18 25 Union Square West 19 10 Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (A-1) W. -

From Wall Street to Astor Place: Historicizing Melville's `Bartleby'

Barbara From Wall Street to Astor Place: Historicizing Foley Melville's "Bartleby" In recent years critics have been calling for a re grounding of mid-nineteenth-century American li terature-of the ro mance in particular- in politics and history. John McWilliams ap plauds the contemporary "challenge to the boundaqless and abstract qualities of the older idea of the Romance's neutral territory." George Dekker notes that recent attempts to "rehistoricize the American ro mance'' have entailed an "insist[ence] that our major romancers have always been profoundly concerned with what might be called the men tal or ideological 'manners' of American society, and that their seem ingly anti-mimetic fictions both represent and criticize those man ners. " 1 But Herman Melville's "Bartleby. the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street" (1853) has to this point been exempted from a thorough going historical recontextualization; its subtitle remains to be fully explained. Not all readings of the tale, to be sure, have been "boundaryless and abstract." Critics interested in the tale's autobiographical dimen sion have interpreted it as an allegory of the writer's fate in a market society. noting specific links with Melville's own difficult authorial career. Scholars concerned wilh the story's New York setting have discovered some important references to contemporaneous events. Marxist critics have argued that "Bartleby" offers a portrait of the increasing alienation of labor in the rationalized capitalist economy that took shape in the mid-nineteenth-century United States.2 But such critical enterprises have remained largely separate, with the result that biography. -

C. of the Late Charles I. Bushnell, Esq., Comprising His Extensive Collections

.^:^ ^-^^ .'';";if^A*' ^^^ ^^^:r i* iififc' ^•i-^*'im v<*^ 5:?^:'/; x^ 11^1 'M QJarttell Unitteraitg Hthtatg Jtljara, New gork FROM THE BENNO LOEWY LIBRARY COLLECTED BY BENNO LOEWY 1854-1919 BEQUEATHED TO CORNELL UNIVERSITY CATALOGUE OK THE LIBRARY, AUTOGRAPHS, EXGRAVINGS, &c. OF THE lATE CHARLES I. BUSH NELL, Esq. TO, BE SOLD BY Bangs & Co. Monday, April 2d, and four following days. 1883. Jln^^ ijj K.h .Jiali I Cornell University j Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924031351798 CATALOGUE OF THE LIBRARY, &e. OF THE LATE CHARLES L BUSHNELL, Esq, COMPRISING HIS EXTENSIVE COLLECTIONS OF RARE AND CURIOUS AMERICANA, OF Engravings, Autographs, Historical Relics, Wood-Blocks Engraved by Dr. Anderson, &c., &c. Compiled by ALEX'R DENHAM. TO BE SOLDAT AUCTION, Monday, April 2d, and four following days. Commencing at 3 P. M. and 7.30 P. M., each day, BY Messrs. BANGS & CO., Nos. 739 and 741 Broadway, New York. Gentlemen unable to attend the Sale, may have purchases made to their order by the Auctio?ieers. 1I^"A11 bids should be made by the Volume, and not by the set. NO T E. The late Mr. Charles I. Bushnell was widely known, not only as a persevering collector of rare and quaint books, but also as a diligent student of American history ; whose thorough knowledge of those minutiae which escape the notice of all but the painstaking specialist had been proved by his original essays and scholarly annotations to various books.