Rousseau in Wootton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B H I J Q L K M O N a E C D G

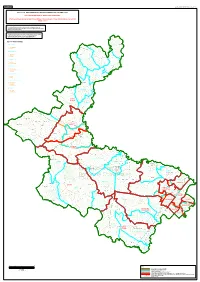

SHEET 1, MAP 1 East_Staffordshire:Sheet 1 :Map 1: iteration 1_D THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EAST STAFFORDSHIRE Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of East Staffordshire June 2020 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. KEY TO PARISH WARDS BURTON CP A ST PETER'S OKEOVER CP B TOWN OUTWOODS CP C CENTRAL D NORTH E SOUTH STANTON CP SHOBNALL CP WOOTTON CP F CANAL G OAKS WOOD MAYFIELD CP STAPENHILL CP RAMSHORN CP H ST PETER'S I STANTON ROAD J VILLAGE UTTOXETER CP ELLASTONE CP K HEATH L TOWN UTTOXETER RURAL CP M BRAMSHALL N LOXLEY O STRAMSHALL WINSHILL CP DENSTONE CP P VILLAGE Q WATERLOO ABBEY & WEAVER CROXDEN CP ROCESTER CP O UTTOXETER NORTH LEIGH CP K M UTTOXETER RURAL CP UTTOXETER CP L UTTOXETER SOUTH N MARCHINGTON CP KINGSTONE CP DRAYCOTT IN THE CLAY CP CROWN TUTBURY CP ROLLESTON ON DOVE CP HANBURY CP DOVE STRETTON CP NEWBOROUGH CP STRETTON C D BAGOTS OUTWOODS CP ABBOTS ANSLOW CP HORNINGLOW BROMLEY CP & OUTWOODS BLITHFIELD CP HORNINGLOW B AND ETON CP E BURTON & ETON G F BURTON CP P SHOBNALL WINSHILL WINSHILL CP SHOBNALL CP HOAR CROSS CP TATENHILL CP Q A BRIZLINCOTE BRANSTON CP ANGLESEY BRIZLINCOTE CP CP BRANSTON & ANGLESEY NEEDWOOD H STAPENHILL I STAPENHILL CP J DUNSTALL CP YOXALL CP BARTON & YOXALL BARTON-UNDER-NEEDWOOD CP WYCHNOR CP 01 2 4 KEY BOROUGH COUNCIL BOUNDARY Kilometres PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY 1 cm = 0.3819 km PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY BAGOTS PROPOSED WARD NAME WINSHILL CP PARISH NAME. -

Wredon & Wardlow Quarries

BCL Document Reference: C/TL/W&W/EIA08.002 Tarmac Limited WREDON & WARDLOW QUARRIES Nr. Cauldon Low, Staffordshire Application for Consolidation of Existing Planning Permissions Hydrogeological and Hydrological Assessment 26th June 2009 Report prepared for: Tarmac Limited Tunstead House BUXTON Derbyshire SK17 8TG Tel. 01298 768444 Fax. 01298 768454 Technology Centre Wolverhampton Science Park, Wolverhampton, WV10 9RU Consultant Hydrogeologists Limited Tel: 01902 824111, Fax: 01902 824112 email: [email protected] web: http://www.bclhydro.co.uk Company Registration Number: 4043373 Registered in England & Wales. Registered Office: 33 Wolverhampton Road, Cannock. This Page Intentionally Left Blank BCL Document Reference: C/TL/W&W/EIA08.002 Tarmac Limited WREDON & WARDLOW QUARRIES Nr. Cauldon Low, Staffordshire Application for Consolidation of Existing Planning Permissions Hydrogeological and Hydrological Assessment 26th June 2009 Report prepared by: Gavin Chaplin B.Sc. M.Sc. Senior Hydrogeologist Report checked by: Henry Lister B.Sc. M.Sc. Senior Hydrogeologist Technology Centre Wolverhampton Science Park, Wolverhampton, WV10 9RU Consultant Hydrogeologists Limited Tel: 01902 824111, Fax: 01902 824112 email: [email protected] web: http://www.bclhydro.co.uk Company Registration Number: 4043373 Registered in England & Wales. Registered Office: 33 Wolverhampton Road, Cannock. This Page Intentionally Left Blank Wredon & Wardlow Quarries, Nr. Cauldon Low, Staffordshire Application for Consolidation of Existing Planning Permissions Hydrogeological -

Premises Licence List

Premises Licence List PL0002 Drink Zone Plus Premises Address: 16 Market Place Licence Holder: Jasvinder CHAHAL Uttoxeter 9 Bramblewick Drive Staffordshire Littleover ST14 8HP Derby Derbyshire DE23 3YG PL0003 Capital Restaurant Premises Address: 62 Bridge Street Licence Holder: Bo QI Uttoxeter 87 Tumbler Grove Staffordshire Wolverhampton ST14 8AP West Midlands WV10 0AW PL0004 The Cross Keys Premises Address: Burton Street Licence Holder: Wendy Frances BROWN Tutbury The Cross Keys, 46 Burton Street Burton upon Trent Tutbury Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE13 9NR Staffordshire DE13 9NR PL0005 Water Bridge Premises Address: Derby Road Licence Holder: WHITBREAD GROUP PLC Uttoxeter Whitbread Court, Houghton Hall Business Staffordshire Porz Avenue ST14 5AA Dunstable Bedfordshire LU5 5XE PL0008 Kajal's Off Licence Ltd Premises Address: 79 Hunter Street Licence Holder: Rajeevan SELVARAJAH Burton upon Trent 45 Dallow Crescent Staffordshire Burton upon Trent DE14 2SR Stafffordshire DE14 2PN PL0009 Manor Golf Club LTD Premises Address: Leese Hill Licence Holder: MANOR GOLF CLUB LTD Kingstone Manor Golf Club Uttoxeter Leese Hill, Kingstone Staffordshire Uttoxeter ST14 8QT Staffordshire ST14 8QT PL0010 The Post Office Premises Address: New Row Licence Holder: Sarah POWLSON Draycott-in-the-Clay The Post Office Ashbourne New Row Derbyshire Draycott In The Clay DE6 5GZ Ashbourne Derbyshire DE6 5GZ 26 Jan 2021 at 15:57 Printed by LalPac Page 1 Premises Licence List PL0011 Marks and Spencer plc Premises Address: 2/6 St Modwens Walk Licence Holder: MARKS -

Elizabeth and Ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey De Vere Society Newsletter

November 2006 Elizabeth and ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey De Vere Society Newsletter Elizabeth and ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey by Jeremy Crick Part I of a short account of the family history of Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford’s second wife and the strategic importance of the Trentham archive in the search for Oxford’s literary fragments. Accompanied by the Trentham family tree incorporating the de Veres and the Sneyds. Introduction Whether it was Oxford’s son-in-law, Philip When I began my study of the Trentham family, Herbert, Earl of Montgomery, and his brother about two years ago, I had one principal thought in William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke - the mind: if any of Edward de Vere’s literary papers - ‘incomparable brethren’ - who were given access to whether notebooks, original drafts or even literary Oxford’s papers (and which may later have been correspondence - have survived undiscovered till consumed by fire in the library at Wilton), or the present, it must be possible to find them. whether it was another son-in-law, William Stanley, Being a passionate Oxfordian these past Earl of Derby, who began the process of preserving twenty-odd years, I’m as fascinated as all Oxford’s life’s work for posterity, we may never Oxfordians are by the remarkable scholarship that know. has illuminated the ‘Shakespearean’ canon with It is very unlikely, however, that Elizabeth concordances from Oxford’s life, alongside the Trentham divested herself of all of Oxford’s literary broader question of whether the Stratford or the papers for the preparation of the First Folio - to the Oxford biography delivers the better candidate. -

Staffordshire 1

Entries in red - require a photograph STAFFORDSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position ST_ABCD06 SK 1077 4172 B5032 EAST STAFFORDSHIRE DENSTONE Quixhill Bank, between Quixhill & B5030 jct on the verge ST_ABCD07 SK 0966 4101 B5032 EAST STAFFORDSHIRE DENSTONE Denstone in hedge ST_ABCD09 SK 0667 4180 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALTON W of Gallows Green on the verge ST_ABCD10 SK 0541 4264 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALTON near Peakstones Inn, Alton Common by hedge ST_ABCD11 SK 0380 4266 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Threapwood in hedge ST_ABCD11a SK 0380 4266 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Threapwood in hedge behind current maker ST_ABCD12 SK 0223 4280 B5032 STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHEADLE Lightwood, E of Cheadle in hedge ST_ABCK10 SK 0776 3883 UC road EAST STAFFORDSHIRE CROXDEN Woottons, between Hollington & Rocester on the verge ST_ABCK11 SK 0617 3896 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHECKLEY E of Hollington in front of wood & wire fence ST_ABCK12 SK 0513 3817 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS CHECKLEY between Fole and Hollington in hedge Lode Lane, 100m SE of Lode House, between ST_ABLK07 SK 1411 5542 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Alstonefield and Lode Mill on grass in front of drystone wall ST_ABLK08 SK 1277 5600 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Keek road, 100m NW of The Hollows on grass in front of drystone wall ST_ABLK10 SK 1073 5832 UC road STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS ALSTONEFIELD Leek Road, Archford Moor on the verge -

Sites with Planning Permission As at 30.09.2018)

Housing Pipeline (sites with Planning Permission as at 30.09.2018) Not Started = Remaining Cumulative Total Outline Planning Application Decision Capacity Under Full Planning Parish Address Capacity For monitoring Completions (on partially Planning Number. Date* of Site Construction completed sites upto & Permission Year Permission including 30.09.18) 2 Mayfield Hall Hall Lane Middle Mayfield Staffordshire DE6 2JU P/2016/00808 25/10/2016 3 3 0 0 0 3 3 The Rowan Bank Stanton Lane Ellastone Staffordshire DE6 2HD P/2016/00170 05/04/2016 1 1 0 0 0 1 3 Stanton View Farm Bull Gap Lane Stanton Staffordshire DE6 2DF P/2018/00538 13/07/2018 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Adjacent Croft House, Stubwood Lane, Denstone, ST14 5HU PA/27443/005 18/07/2006 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Land adjoining Mount Pleasant College Road Denstone Staffordshire ST14 5HR P/2014/01191 22/10/2014 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Proposed Conversion Doveleys Rocester Staffordshire P/2015/01623 05/01/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Dale Gap Farm Barrowhill Rocester Staffordshire ST14 5BX P/2016/00301 06/07/2016 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Brown Egg Barn Folly Farm Alton Road Denstone Staffordshire P/2016/00902 24/08/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Alvaston and Fairfields College Road Denstone ST14 5HR P/2017/00050 10/08/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 1) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/00571 17/08/2017 5 0 5 0 5 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 2) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/01180 08/12/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 adj Cherry Tree Cottage Hollington Road Rocester ST14 5HY P/2018/00585 09/07/2018 1 -

Bryn Mar Ellastone

Bryn Mar Dove Street, Ellastone, Ashbourne, DE6 2GY A spacious four bedroom end cottage with detached stone garage and large driveway to rear. Located in the highly sought after village of Ellastone. Comprising Sitting Room, Living Room, Study/Dining Room, Breakfast Kitchen, Inner Hall, Ground Floor Bathroom, Conservatory, First Floor Landing, Four Well Proportioned Bedrooms, Detached Garage, Large Driveway, Gardens Guide Price £299,950 This spacious four bedroomed end cottage is located in the highly sought fitted Bathroom with a cream suite including bath, vanity unit with after village of Ellastone providing spacious and well planned wash basin, electric shower over and fully tiled. accommodation including three reception rooms. It is approximately 1300 sq.ft gross internal area. There is a detached stone garage to the First Floor Landing rear with a large driveway providing ample parking. Master Bedroom with dual aspect windows including views over countryside. Bedroom Two has a fitted wardrobe and airing cupboard. Ellastone is a sought after village on the Staffordshire side of the There are Two further Bedrooms. Staffordshire/Derbyshire border. It has a village pub called the Duncombe Arms which is a very well renowned traditional country pub. Outside The village also offers tennis courts, bowling green park, village hall and Side tradesmans entrance leading to the rear garden having a paved church. patio, display borders and a gazebo archway leading to a further paved area with a large detached stone Garage with power and lighting, and The property is offered with no chain and a viewing is highly ample parking with gated access off Mill Lane. -

The Season Opens in Walsall

Step Out April issue, 2013 STAFFORDSHIRE AREA RAMBLERS The Ramblers’ Association is a registered charity (number 1093577) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (number 4458492). The opinions expressed in Stepout are not necessarily the official views of the RA, Area or National, but those of the authors concerned Issue 8 Photo – Winter- Marchington Woods Editorial Much to my, and everyone else’s, surprise, there is a lot of snow for the end of March. In fact it was quite exciting walking in my local Country Park where one minute I was walking on bare ground and the next knee, or even waist deep in snow. In fact I saw two six foot drifts and all this within the city limits of Stoke on Trent. Once again it shows that you do not have to go far away to have a good walk. Personally I think we are very lucky in our county as we have almost everything from high moors to gentle lowlands, forests to fields and miles of canals. Something for everybody. However it does not mean that we should be complacent about our walking. In Stoke on Trent there are many different walking clubs and sadly, few, appreciate the problems in keeping our rights of way open and accessible. As last year, this edition is a reflection of the work done behind the scenes both by our Area and Group volunteers. Without them, many of our walks would simply become unwalkable. Full Circle. I wrote an article for this Area magazine in 1994 when I was Area Chairman. -

The Nook, 2 Smiths Yard Mayfield, Ashbourne, DE6 2LE

The Nook, 2 Smiths Yard Mayfield, Ashbourne, DE6 2LE A two bedroom mid cottage set in the popular village of Mayfield. Lounge, Cellar Kitchen, Two Bedrooms over two floors, Bathroom and Small Patio Area to rear. Guide Price £95,000 www.JohnGerman.co.uk Confidently This attractive two bedroom mid cottage is located in a popular Bathroom village near the historic town of Ashbourne and would make an 1.90m x 1.50m (approx. 6’3” x 5’0”). Comprising bath with ideal holiday let, investment or first time buy. Viewing is shower attachment over and shower screen, low level w.c. and recommended. pedestal wash hand basin. Part tiled walls and double glazed window to rear. Directions From Ashbourne follow the A52 towards Leek. Turn right at the Second Floor Bedroom Two island onto the A52 for approximately 0.8 miles. Turn left towards 4.43m max into eaves x 3.66m (approx. 14’3” max into eaves x Mayfield and Ellastone (B05032). Follow up the hill and the 12’0”). Exposed purlins, radiator, double glazed window to side property will be located on the left hand side. and door to walk-in wardrobe or potential en suite. Accommodation Outside Entrance door to: Rear Small yard with patio area. Lounge 4.35m max, 3.50m min x 3.83m max (approx. 14’2” max, 11’6” min Tenure x 12’6” max). Stone fireplace with space for fire, radiator, double Freehold. Please note there is a Flying Freehold with the glazed windows to front and rear, stairs off to first floor and stairs bathroom. -

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications Below, Please Use the Following Link

Printed On 22/08/2016 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 34/2016 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 15/08/2016 TO 19/08/2016 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 409,158.00 : 323,391.00 P/2016/01068 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Householder Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Demolition of existing detached garage to facilitate the erection of two storey side and single storey front and rear extensions Barkley House For Mr A Ufton Pinfold Lane c/o Channel Design Ltd Bromley Hurst 5 The Channel Abbots Bromley Ashbourne Staffordshire Derbyshire WS15 3AF DE6 1FB REFERENCE Grid Ref: 409,223.00 : 325,103.00 P/2016/01102 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Change of Use Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Conversion and alterations to existing annexe to form to dwelling house The Annexe For Mr A Smith Radmore Wood Farm c/o C T Planning Ltd Radmore Lane Trafalgar House Abbots Bromley 20a Market Street Staffordshire Lichfield WS15 3AS Staffordshire WS13 6LH Page 1 of 11 Printed On 22/08/2016 Weekly List ESBC LIST No: 34/2016 REFERENCE Grid Ref: 424,164.00 : 322,330.00 P/2016/00890 Parish(s): Anglesey Householder Ward(s): -

East Staffordshire Local Plan

East Staffordshire Local Plan Planning for Change Preferred Option July 2012 Foreword The Local Plan is the blueprint for how East Staffordshire will develop over the next twenty years or so to deliver sustainable communities, economic prosperity and a place where people want to be. Change and development can be a two edged sword which moves us from the present into the future, and I recognise that it is something which many of us don’t always feel comfortable with. However, change and development is necessary if we are to meet our future needs, and can be a positive force for good. East Staffordshire is an attractive place to live, work and invest. It is important we capitalise on our strengths, including our good transport links, attractive towns, diverse economy, strong sense of heritage, varied landscapes, and a strong rural economy. The new Local Plan is about setting and delivering a vision for how we want the Borough to develop and change, but also about how we preserve and enhance what is already special about it. The Local Plan is our prospectus to encourage inward investment for the benefits of all our communities. It is right that we cherish our heritage but we also have to look forward to ensure prosperity for future generations and improving the quality of life to meet their aspirations. Much has changed since we first embarked on the journey to create a new planning framework for East Staffordshire, including the national planning system which is undergoing further reform. In the Autumn of 2011 we consulted on three Strategic Options, and from that consultation and those that went before, we have developed our Preferred Option. -

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications Below, Please Use the Following Link

Printed On 29/08/2017 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 35/2017 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 21/08/2017 TO 25/08/2017 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 407,607.00 : 324,676.00 P/2017/00939 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Erection of a dwelling and detached garage Land to the rear of For Mr Sid Slater Bromley House Uttoxeter Road c/o Andrew Gifford Architects Abbots Bromley Trafalgar House Staffordshire 20A Market Street WS15 3EG Lichfield Staffordshire WS13 6LH REFERENCE Grid Ref: 406,392.00 : 324,517.00 P/2017/01030 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Householder Ward(s): ABROMLEY Bagots Retention of a panel fence and associated landscaping scheme Yeatsall Cottage For Mr Anthony Higgott Uttoxeter Road Yeatsall Cottage Abbots Bromley Uttoxeter Road Staffordshire Abbots Bromley WS15 3BR Staffordshire WS15 3BR Page 1 of 12 Printed On 29/08/2017 Weekly List ESBC LIST No: 35/2017 REFERENCE Grid Ref: 418,473.00 : 324,799.00 P/2017/00918 Parish(s): Anslow Planning Condition Ward(s): Tutbury and Outwoods Application under Section