Cosplay in Australia: (Re)Creation and Creativity Assemblage and Negotiation in a Material and Performative Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Cosplay?

NO, REALLY: WHAT IS COSPLAY? Natasha Nesic A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a B. A. in Anthropology with Honors. Mount Holyoke College May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “In anthropology, you can study anything.” This is what happens when you tell that to an impressionable undergrad. “No, Really: What is Cosplay?” would not have been possible without the individuals of the cosplay community, who gave their time, hotel room space, and unforgettable voices to this project: Tina Lam, Mario Bueno, Rob Simmons, Margaret Huey, Chris Torrey, Chris Troy, Calico Singer, Maxiom Pie, Cassi Mayersohn, Renee Gloger, Tiffany Chang, as well as the countless other cosplayers at AnimeNEXT, Anime Expo, and Otakon during the summer of 2012. A heap of gratitude also goes to Amanda Gonzalez, William Gonzalez, Kimberly Lee, Patrick Belardo, Elizabeth Newswanger, and Clara Bertagnolli, for their enthusiasm for this project—as well as their gasoline. And to my parents, Beth Gersh-Nesic and Dusan Nesic, who probably didn’t envision this eight years ago, letting me trundle off to my first animé convention in a homemade ninja getup and a face full of Watercolor marker. Many thanks as well to the Mount Holyoke College Anthropology Department, and the Office of Academic Deans for their financial support. Finally, to my advisor and mentor, Professor Andrew Lass: Mnogo hvala za sve. 1 Table of Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................................3 -

Bleach, Vol. 48 Online

4sXIc (Read free) Bleach, Vol. 48 Online [4sXIc.ebook] Bleach, Vol. 48 Pdf Free Tite Kubo *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #760728 in Books Tite KuboModel: FBA-|324363 2012-10-02 2012-10-02Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 7.50 x .70 x 5.00l, .41 #File Name: 142154301X216 pagesBleach Volume 48 | File size: 51.Mb Tite Kubo : Bleach, Vol. 48 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Bleach, Vol. 48: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ... story omg and how it end OMG bleach is amazing.By Ely GomezWhat at story omg and how it end OMG bleach is amazing.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Of course I love it!By CandyceBeing a Bleach fan, I had to buy this one. I collect many of the Shonen Jump sets and this had to be included. Great read, like all of the others!1 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Yay, Aizen!By K Lynne LoweThis is a grrrrreat moment in the series! Also, this one would be appreciated by any art student interested in drawingLove for Aizen, that hogyoku absorbed wretch! A paranormal action-adventure about sword-wieldingReads R to L (Japanese Style). Ichigo Kurosaki never asked for the ability to see ghosts--he was born with the gift. When his family is attacked by a Hollow--a malevolent lost soul-- Ichigo becomes a Soul Reaper, dedicating his life to protecting the innocent and helping the tortured spirits themselves find peace. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

![Skripsi IP Galih Dwi Ramadhan 14410359 ]LEGAL PROTECTION](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9665/skripsi-ip-galih-dwi-ramadhan-14410359-legal-protection-249665.webp)

Skripsi IP Galih Dwi Ramadhan 14410359 ]LEGAL PROTECTION

LEGAL PROTECTION OF COSPLAY COSTUME BASED ON INDONESIA AND JAPAN’S COPYRIGHT AND DESIGN LAW A THESIS By: GALIH DWI RAMADHAN Student Number: 14410359 INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF LAW UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 LEGAL PROTECTION OF COSPLAY COSTUME BASED ON INDONESIA AND JAPAN’S COPYRIGHT AND DESIGN LAW A THESIS Presented as the Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements To Obtain the Bachelor Degree at the Faculty of Law Universitas Islam Indonesia Yogyakarta By: GALIH DWI RAMADHAN Student Number: 14410359 INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF LAW UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 i LEGAL PROTECTION OF COSPLAY COSTUME BASED ON INDONESIA AND JAPAN’S COPYRIGHT AND DESIGN LAW A BACHELOR DEGREE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of theRequirements to Obtain the Bachelor Degree at the Faculty of Law, Islamic University of Indonesia, Yogyakarta By: GALIH DWI RAMADHAN 14410359 Department: International Business Law INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF LAW ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2016 ii iii SURAT PERNYATAAN ORISINALITAS KARYA TULIS ILMIAH BERUPA TUGAS AKHIR MAHASISWA FAKULTAS HUKUM UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA Yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini, saya: Nama : GALIH DWI RAMADHAN No. Mahasiswa : 14410359 Adalah benar-benar mahasiswa Fakultas Hukum Universitas Islam Indonesia Yogyakarta yang telah melakukan Penulisan Karya Tulis Ilmiah (Tugas Akhir) berupa Skripsi dengan judul: LEGAL PROTECTION OF COSPLAY COSTUME BASED ON INDONESIA AND JAPAN’S COPYRIGHT AND DESIGN LAW Karya ilmiah ini akan saya ajukan kepada Tim Penguji dalam Ujian Pendadaran yang diselenggarakan oleh Fakultas Hukum UII. Sehubungan dengan hal tersebut, dengan ini saya menyatakan: 1. Bahwa karya tulis ilmiah ini adalah benar-benar hasil karya sendiri yang dalam penyusunannya tunduk dan patuh terhadap, kaidah, etika, dan norma-norma penulisan sebuah karya tulis ilmiah sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku; 2. -

Event Highlights

Event Highlights Events • Yoshihiro Ike: Anime Soundtrack World sponsored by Studio Kitchen: International debut performance of one of Japan’s most prolific music composers in the industry featuring a 50 piece orchestra that will bring to life the greatest collection of soundtracks from Tiger & Bunny, Saint Seiya, B: The Beginning, Dororo, Rage of Bahamut:Genesis, and Shadowverse. • 4DX Anime Film Festival: Featuring Detective Conan: Zero The Enforcer, Mobile Suit Gundam NT (Narrative) and Mobile Suit Gundam 00 the MOVIE – A Wakening of the Trailblazer- enhanced with immersive, multi-sensory 4DX motion and environmental effects. • Anime Expo Masquerade & World Cosplay Summit US Finals • Inside the World of Street Fighter & Street Fighter V: Arcade Edition - Ultimate Cosplay Showdown sponsored by Capcom • LOVE LIVE! SUNSHINE!! Aqours World LoveLive! in LA ~BRAND NEW WAVE~ • Fate/Grand Order USA Tour • Fashion Show: Featuring Japanese brands h. NAOTO with designer Hirooka Naoto, Acryl CANDY with guest model Haruka Kurebayashi, amnesiA¶mnesiA with guest model Yo from Matenrou Opera, and Metamorphose with designer Chinatsu Taira. In addition, Hot Topic will reveal a new collection and HYPLAND will debut new items from their BLEACH collaboration. Programming • 15+ Premieres & Exclusive Screenings: Promare, Dr. Stone, In/Spectre, Human Lost, Fire Force, My Hero Academia Season 4, “Pokémon: Mewtwo Strikes Back—Evolution!” and more. • 900+ Hours of Panels, Events, Screenings, Workshops, and more. • Programming Tracks: Career, Culture, Family, and Academic Program. • Pre-Show Night on July 4 (6 - 10pm) 150+ Guests & Industry Appearances • Creators: Katsuhiro Otomo, Bisco Hatori, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Yusuke Kozaki, Atsushi Ohkubo, Utako Yukihiro. • Japanese Voice Actors: Rica Matsumoto, Mamoru Miyano, Maya Uchida, Kaori Nazuka. -

Bleach, the Final Frontier

BLEACH, THE FINAL FRONTIER By dj Date Masamune Also, friendly reminder from Kenpachi-sama… Need to Knows • Panel will be available online + my resources on my blog • Will upload .pdf of PowerPoint that will be available post-con • Contact info. • Take a business card before you leave • If you have any questions left, feel free to ask me after the panel or e-mail me • ‘Discussion panel’ is nothing w/o the discussion part ~^.^~ How It’s Going to Be… • For every arc, I’ll do a super quick, super basic summation (accompanied by a crapload of pics), then everyone else can add in their own things, move the crap on rapidly, rinse & repeat • i.e., everyone gets a chance to talk • So, none of that “anime expert”/“I know more than the panelist” b.s. • Important mindset to have: Bleach is a recently ended train wreck you can never look away from Tite Kubo Audience SO LET’S GET STARTED~! & may kami-sama help us all ~.~; AGENT OF THE SHINIGAMI, SNEAK ENTRY, & THE RESCUE ARC Episodes 1-63 Manga: 1-182 Ishida Uryuu Chad Yasutora Ichigo Kurosaki Orihime Inoue Chizuru Honsho Mizuiro Kojima Asano Keigo Tatsuki Arisawa Mizuho Asano Yuzu & Karin Don Kanonji Kon Genryusai Yamamoto Soi Fon Gin Ichimaru Retsu Unohana Sousuke Aizen Zanpakuto: (Sui-Feng) Zanpakuto: Zanpakuto: Zanpakuto: Ryujin Jakka Zanpakuto: Shinsou Minazuki Kyoka Suigetsu Suzemabachi Zanpakuto: Bankai: Bankai: Bankai: Zanka no Tachi Kamishini no Yari *Suzumushi Jakuho Raikoben Bankai: Zanpakuto: Zanpakuto: Suzumushi Senbonzakura Tenken Tsuishiki: Enma Bankai: Bankai: Zanpakuto: Korogi Senbonzakura -

Salado Rain on Rooftops Means It's Time for Ferguson to Go Back To

Salado Villageillage Voiceoice VOL. XLII, NUMBER 5 VTHURSDAY, MAY 16, 2019 254/947-5321 V SALADOviLLAGEVOICE.COM 50¢ After reception BoA gets to work on annexation BY TIM FLEISCHER EDitOR-in-CHIEF Prior to the regular meet- ing of the Board of Alder- men, a reception will honor outgoing aldermen Michael McDougal, who has served six years on the board, and Andy Jackson, who has served two. The reception will begin at 6 p.m. May Michael McDougal 16. During the meeting that starts at 6:30 p.m., incoming aldermen Rodney W. Bell, Valedictorian Grace Barker Salutatorian Sarah Umpleby John Cole and Dr. Amber Preston-Dankert will be giv- en their oaths of office. The Top grads named for Class of 2019 board will then appoint a With graduation near, Spanish 1-3 and Computer Salutatorian AP Statistics, AP Calculus Mayor Pro Tem for the year. Salado High School has Science and AP in English She has attended school Sarah Umpleby is the Village of Salado alder- named its top two graduates Language, English Litera- in Salado for nine years. 2019 Salado High School Sa- men will conduct the second for 2019: Grace Barker and ture, Calculus, Biology, US During that time she has lutatorian with a final grade set of public hearings May Sarah Umpleby. History, US Government, been a member of National Andy Jackson point average of 111.154. 16 for the annexations of Macroeconomics, World Honor Society; Mu Alpha She is the daughter of Salado ISD properties and of the boundaries of the pro- Valedictorian History, Spanish Language Theta (math honor society); Jennifer and John Umpleby rights of way. -

W17-St-Martins-Press.Pdf

ST. MARTIN'S PRESS DECEMBER 2016 Untitled Body Book Anonymous A new and exciting diet and exercise book from widely followed personal trainer Kayla Itsines. More information coming soon. More information coming soon. HEALTH & FITNESS / EXERCISE St. Martin's Press | 12/27/2016 9781250121479 | $26.99 / $37.99 Can. Hardcover | 256 pages | Carton Qty: 9.3 in H | 6.1 in W Subrights: UK: Pan Macmillan UK Translation: Pan Macmillan AU Other Available Formats: Ebook ISBN: 9781250121486 MARKETING Author Appearances National Television Publicity National Radio Publicity National Print Publicity Online Publicity Major Online Advertising Campaign Extensive Blog Outreach Major Social Media Campaign Email Marketing Campaign 2 ST. MARTIN'S PRESS FEBRUARY 2017 Echoes in Death J. D. Robb The new novel featuring lieutenant Eve Dallas from the #1 New York Times bestselling author THE #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING SERIES . The chilling new suspense novel from the author of Brotherhood in Death. After a party in New York, Lieutenant Eve Dallas rides home with her billionaire husband, Roarke, happy to be done with cocktails and small talk. After another party, not far away, a woman retires to her bedroom with her husband—and walks into a brutal nightmare. FICTION / ROMANCE / Their paths are about to collide… SUSPENSE St. Martin's Press | 2/7/2017 9781250123114 | $27.99 / $38.99 Can. When the young woman—dazed, naked, and bloody—wanders in front of Hardcover | 400 pages | Carton Qty: their car, Roarke slams on the brakes just in time, and Eve, still in glittering 9.3 in H | 6.1 in W gown and heels, springs into action. -

Japanese Manga and Its Buds Lynne, Miyaki Final Project Bleach

Priest 1 Alexander Priest May 2013 Jpnt 179 Graphically Speaking: Japanese Manga and Its Buds Lynne, Miyaki Final Project Bleach ‘Live Action’ Screenplay This is a satirical screenplay of the manga series created by Tite Kubo. Priest 2 Introduction: There haven’t been many American ‘live action’ movie adaptations of manga. There was a brief period, where movies Speed Racer (2008), Astro Boy (2009), and Dragonball Evolution (2009) debuted and theatres, but they would receive negative or mixed reception. To commemorate these movies, I have drafted an intentionally horrible screenplay for my imaginary movie, Bleach: Soul Reaper ™. Unfortunately, I was not able to create that would actually span an entire movie. A myriad of difficulties and challenges embodies the difficulties that come with creating these adaptations in the first place. Firstly, I have had a lack of experience in screenplay writing. My second struggle came with adapting the much-loved Bleach and trying to corrupt it for the sake of satire. Maintaining a coherent storyline is difficult when you are also trying tamper with existing plots and storylines. Adaptations will always contradict the source material, it is inevitable, but much effort goes in deciding what should and shouldn’t be changed. Successfully fulfilling the notion of a “terrible adaptation” proves more challenging than initially expected. Thirdly, I didn’t know how to keep the screenplay informative without inserting footnotes to provide context and justification. The purpose of this project is to reveal common mistakes and disastrous trends within American interpretations of Japanese source materials, so I created a portion of a live-action screenplay that embodies this. -

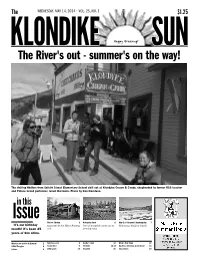

The River's out - Summer's on the Way!

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 • VOL. 25, NO. 1 $1.25 KLONDIKE Happy Breakup! SUN The River's out - summer's on the way! The visiting fiddlers from Selkirk Street Elementary School chill out at Klondyke Cream & Candy, shepherded by former RSS teacher and Palace Grand performer, Grant Hartwick. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Fire on 7th Ave. 3 Kokopelle farm 6 May 2 is this year's breakup day 7 It's our birthday Cigarettes lit this Yukon Housing Part of Sunnydale returns to its Next comes the ferry launch. Max’s New month! It's been 25 unit. farming roots. Summer Hours years of Sun shine. What to see and do in Dawson! 2 New taco cart 8 Gertie's story 12 What's Your Story 22 Uffish Thoughts 4 Family Time 9 TV Guide 14-18 Business Directory & Job Board 23 Letters 5 SOVA grads 10 Stacked 20 City notices 24 P2 WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: hatha yoga With jOanne van nOstranD: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many Tuesdays and Thursdays, 5:30- activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and 7SOVA p.m. E-mail [email protected] 24 hours in advance. planning, so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at [email protected]. aDMin Office hOurs DAWSON CITY INTERNATIONAL GOLD SHOW: liBrarY hOurs : Monday to Thursday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. -

The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to Denfur 2021!

DenFur 2021 The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to DenFur 2021! I wanted to introduce myself to you all now that I am the new con chair for DenFur 2021! My name is Boiler (or Boilerroo), but you can call me Mike if you want to! I've been in the furry fandom since 1997 (24 years in total!) – time flies when you're having fun! I am a non-binary transmasc person and I use he/hIm pronouns. If you don't know what that means, you are free to ask me and I will explain – but in sum: I am trans! I am also an artist, part time media arts instructor and a full-time librarian in my outside-of-furry life. I am very excited to usher in the next years of DenFur – I know the pandemic has really been an unprecedented time in our lives and affected us all deeply, but I am hoping with the start of DenFur we can reunite as a community once more, safely and with a whole lot of furry fun! Of course, we will have a lot of rules, safeguards and requirements in place to make sure that our event is held as safely as possible. Thank you everyone for your patience as we have worked diligently to host this event! I hope you all have an amazing convention, and be sure to say hello! TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 Page 9 Con Chair Welcome Staff Page 4 Page 10 Theme Dealers Den List Table of contents and artist credit for pages Page 5 Page 11-13 Convention Operating Hours Schedule Grid Page 6 Page 14-21 Convention Map Panel Information and Events Page 7 Page 22 Guests of Honor Altitude Safety Page 8 Page 23-24 Charity Convention Code of Conduct ARTIST CREDIT Page 1 Page 11 Foxene Foxene Page 2 Page 20 RedCoatCat Ruef n’ Beeb Page 4 Page 22 Boiler Ruef n’ Beeb Page 5 Page 23 Basil Boiler Page 6 Page 26 Basil Ritz Page 9 Basil On Our Journey In AD 136:001:20:50,135 years after the first contact between the Protogen and the furry survivors, the ACC-1001 Denfur launched a crew of 2500 furries into space. -

Pros and Cons: Anime Conventions and Cosplayers

PROS AND CONS: ANIME CONVENTIONS AND COSPLAYERS by Angela Barajas THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology at The University of Texas at Arlington December 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: David Arditi, Supervising Professor Kelly Bergstrand Heather Jacobson Copyright by Angela Barajas 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. David Arditi, my thesis advisor, for encouraging me to think critically about all of my work, especially culture. I would also like to thank Dr. Heather Jacobson and Dr. Kelly Bergstrand for their support as my thesis committee. Thank you all. i DEDICATION I would like to thank my family and friends who have supported me through this thesis project and my overall academic career. They have been there to bounce ideas off and complain to. Thank you for your interest in my work. ii ABSTRACT Pros and Cons: Anime Conventions and Cosplayers Angela Barajas, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professor: David Arditi Among the brightly-hued convention (con) halls, people dressed in feathers, foam armor, and spandex pose for pictures with one another as cosplayers. Cosplay is a way for fans to present themselves and their group to the fan community on a con-wide scale. Originally, I planned to investigate how cosplayers navigate their identities as cosplayers and as members of mainstream American society and how do these two identities inform each other. I sought to understand cosplayer’s identities as laborers within their cosplay groups. Using ethnographic research methods, I interviewed eleven participants and conducted participant observations.