Regulatory Overreaching: Why the FCC Is Exceeding Its Authority in Implementing a Phase-In Plan for DTV Tuners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) EchoStar Technologies L.L.C. ) ) Petition for Waiver of Section 15.117(b) of the ) Commission’s Rules ) ECHOSTAR TECHNOLOGIES L.L.C. PETITION FOR WAIVER Pursuant to Section 1.3 of the Commission’s rules,1 EchoStar Technologies L.L.C. (“EchoStar”) respectfully requests the Media Bureau (“Bureau”) to waive the “all channels” requirement in Section 15.117(b) of the Commission’s rules to permit the importation, marketing, and sale of a new model of “SlingLoaded” high-definition (“HD”), Internet-enabled, digital video recorder (the “SlingLoaded DVR”) that does not include an analog over-the-air tuner.2 The Bureau and the Office of Engineering and Technology (“OET”) to date have interpreted the “all channels” provision to mean that any TV receiver that includes an over-the- air digital (ATSC) tuner must also include an over-the-air analog (NTSC) tuner.3 However, the 1 47 C.F.R. § 1.3. 2 See 47 C.F.R. § 15.117(b). Section 15.117 provides, in relevant part, that “[all] TV broadcast receivers [shipped in interstate commerce or imported into the United States, for sale or resale to the public] shall be capable of adequately receiving all channels allocated by the Commission to the television broadcast service.” 47 C.F.R. § 15.117(a), (b). For purposes of this rule, the term “TV broadcast receivers” includes “devices, such as … set-top devices that are intended to provide audio-video signals to a video monitor, that incorporate the tuner portion of a TV broadcast receiver and … can be used for off-the-air reception of TV broadcast signals.” Id. -

ATSC Standard: Service Usage Reporting (A/333)

ATSC A/333:2017 Service Usage Reporting 4 January 2017 ATSC Standard: Service Usage Reporting (A/333) Doc. A/333:2017 4 January 2017 Advanced Television Systems Committee 1776 K Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 202-872-9160 i ATSC A/333:2017 Service Usage Reporting 4 January 2017 The Advanced Television Systems Committee, Inc., is an international, non-profit organization developing voluntary standards for digital television. The ATSC member organizations represent the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. Specifically, ATSC is working to coordinate television standards among different communications media focusing on digital television, interactive systems, and broadband multimedia communications. ATSC is also developing digital television implementation strategies and presenting educational seminars on the ATSC standards. ATSC was formed in 1982 by the member organizations of the Joint Committee on InterSociety Coordination (JCIC): the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), the National Cable Telecommunications Association (NCTA), and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). Currently, there are approximately 150 members representing the broadcast, broadcast equipment, motion picture, consumer electronics, computer, cable, satellite, and semiconductor industries. ATSC Digital TV Standards include digital high definition television (HDTV), standard definition television (SDTV), data broadcasting, multichannel surround-sound audio, and satellite direct-to-home broadcasting. Note: The user's attention is called to the possibility that compliance with this standard may require use of an invention covered by patent rights. By publication of this standard, no position is taken with respect to the validity of this claim or of any patent rights in connection therewith. -

Television Compatibility

Television Compatibility The CWRU digital cable system requires a television, DVR or other tuner device with a QAM tuner. You must check the specifications from your manufacturer to determine if it includes the required tuner. The types of tuners currently in use in the United States are listed here for your reference. NTSC TUNER (NOT COMPATIBLE) NTSC, named for the National Television System Committee, is the analog television system used in the United States from 1941 to 2009. After nearly 70 years of use, the FCC ordered the discontinuation of most over-the-air NTSC transmissions in the United States in 2009. Analog channels are still available on many cable systems to provide basic programming without the use of a cable conversion box. Some manufacturers no longer include this type of tuner in televisions built after 2009. ATSC TUNER (NOT COMPATIBLE) An ATSC (Advanced Television Systems Committee) tuner, often called an ATSC receiver or HDTV tuner is a type of television tuner that allows reception of digital television (DTV) television channels transmitted by television stations in North America. The FCC required all television manufacturers to include an ATSC tuner in all products since 2007, and required television broadcasters to switch in 2009. This type of tuner is currently included in all new televisions, including the inexpensive "digital conversion boxes" that were widely available leading up to the 2009 switchover. QAM TUNER (REQUIRED) QAM (quadrature amplitude modulation) is the format by which digital cable channels are encoded and transmitted via cable television providers, including CWRU. A QAM tuner is the cable equivalent of an ATSC tuner which receives over-the-air digital channels broadcast by local television stations. -

USB ATSC Tuner

90-day Limited Warranty Sima Products Corporation warrants this product against defects in materials and workmanship for a period of 90 days from the date of purchase. During the warranty period, the product will be repaired or replaced at Sima’s option. Mail the enclosed product registration card within ten days of the original purchase. TV Anywhere ATSC Tuner Conditions Model DTU-100 Quickstart Guide Ship your unit, freight pre-paid, including a copy of your sales receipt and a description of problem to: Sima Products Corporation Attn: Customer Service 140 Pennsylvania Ave. Bldg. #5 Oakmont, PA 15139 This warranty is void if any defects are caused by abuse, misuse, negligence or unauthorized repairs. All liability for incidental or consequential damages is specifically excluded. Some states do not allow for the exclusion or limitation of incidental or consequential damages, so the above limitation or exclusion may not apply to you. This warranty gives you specific legal rights and you may have other rights, which vary from state to state. Sima Products Corporation 140 Pennsylvania Ave Bldg #5 Oakmont, PA 15139 Please register online at www.simacorp.com www.simaproducts.com PN 21754 © 2007 Sima Products Corporation Page 24 Notes Page 2 Page 23 Package Contents...........................................................................................4 16. Can TotalMedia create 16:9 DVD-video discs from Introduction .....................................................................................................6 captured 16:9 TV shows -

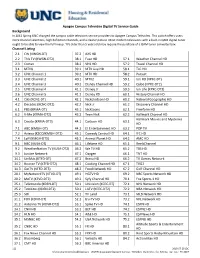

Channel and Setup Guide

Apogee Campus Televideo Digital TV Service Guide Background In 2013 Spring UNC changed the campus cable television service providers to Apogee Campus Televideo. This switch offers users more channel selections, high definition channels, and a clearer picture. Most modern televisions with a built-in QAM digital tuner ought to be able to view the full lineup. TVs older than 5 years old may require the purchase of a QAM tuner converter box. Channel Listing 2.1 CW (KWGN-DT) 37.2 AXS HD 2.2 This TV (KWGN-DT2) 38.1 Fuse HD 57.1 Weather Channel HD 2.3 Comet 38.2 VH1 HD 57.2 Travel Channel HD 3.1 MTVU 39.1 MTV Live HD 58.1 TLC HD 3.2 UNC Channel 1 39.2 MTV HD 58.2 Pursuit 3.3 UNC Channel 2 40.1 MTV2 59.1 Ion HD (KPXC-DT) 3.4 UNC Channel 3 40.2 Disney Channel HD 59.2 Qubo (KPXC-DT2) 3.5 UNC Channel 4 41.1 Disney Jr 59.3 Ion Life (KPXC-DT3) 3.6 UNC Channel 5 41.2 Disney XD 60.1 History Channel HD 4.1 CBS (KCNC-DT) 42.1 Nickelodeon HD 60.2 National Geographic HD 4.2 Decades (KCNC-DT2) 42.2 Nick Jr 61.2 Discovery Channel HD 6.1 PBS (KRMA-DT) 43.1 Nicktoons 62.1 Freeform HD 6.2 V-Me (KRMA-DT2) 43.2 Teen Nick 62.2 Hallmark Channel HD Hallmark Movies and Mysteries 6.3 Create (KRMA-DT3) 44.1 Cartoon HD 63.1 HD 7.1 ABC (KMGH-DT) 44.2 E! Entertainment HD 63.2 POP TV 7.2 Azteca (KZCO/KMGH-DT2) 45.1 Comedy Central HD 64.1 IFC HD 7.4 Laff (KMGH-DT3) 45.2 Animal Planet HD 64.2 AMC HD 9.1 NBC (KUSA-DT) 46.1 Lifetime HD 65.1 ReelzChannel 9.2 WeatherNation TV (KUSA-DT2) 46.2 We TV HD 65.2 TBS HD 9.3 Justice Network 47.1 Oxygen 66.1 TNT HD 14.1 UniMás (KTFD-DT) -

TV Station HD Camera Flexibility: Ready for ATSC M/H & Hyperlocal

THE REPORT 2010 TV Station HD Camera Flexibility: Ready for ATSC M/H & Hyperlocal & 4G? Affordable Investment – Low Operating Costs HD Broadcast Quality – Supports New TV Station Business Model Maximizing Market Opportunities & ROI A Win-Win JVC Broadcast Direct Relationship HD ENG Hyperlocal Handheld HD STUDIO HD ENG Shoulder JVC Professional Products Page 1 of 56 Copyright 2010 All rights reserved Table of Content Page EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW 3 A New Local TV Business Model 3 ATSC M/H & HD ENG 4 And don’t sell your 6MHz OTA space 6 EvaluatinG Hyperlocal TV News? 7 Fast “Go-to-Air” Workflow - HiGh Professional Picture Quality 8 Affordable Investment 8 Invest in HD News facilities – Dominant HDTV screen size 11 HD News Studio Camera – Low OperatinG Costs 12 Metro-centric Competitive StrateGy 12 A New TV Broadcast Business Model – Common Sense EnG. Director 13 ProHD Super-compression at 35 Mbps VBR 14 PreservinG the Ultimate Live HD Delivery Chain 16 WHAT IS ProHD? 17 ProHD On-Board RecordinG Exclusive 18 Professional Flash Memory StoraGe Media 19 Super-fast SxS is now ProHD 20 Cost-effective Memory Card Archive 21 Native File (Fast-to-Air) Acquisition 22 GY-HM790 Solid State Media Camcorder 23 A New Level of HD Camcorder Flexibility 24 TRIPLEX Offset TechnoloGy - Full resolution choice: 720p and 1080i 25 Professional DockinG SxS Memory Card Media Recorder 26 GY-HM100 Solid State Media Camcorder 26 LIBRE Microwave Camera-back System 26 SxS & SDHC -- Interface to any Laptop, any Desktop 27 ProHD is: Local HD Studio Live 28 HIGHER RATINGS -- -

CONTENTS Ver 4.0

CONTENTS ver 4.0 Getting Started............................................................... 3 Specifications ........................................................................................................... 5 Opening the Package................................................................................................ 9 Installation................................................................................................................ 9 Important Safety Guidelines................................................................................... 10 Television Antenna Connection Protection ............................................................ 13 Product Browse ...................................................................................................... 15 Display.......................................................................................................... 15 Note: wall-mounted ...................................................................................... 16 TV Info Explained ........................................................................................ 19 Source PC & AV Explained .......................................................................... 19 Media Box .................................................................................................... 21 Media Box Rear View Connector Definitions .............................................. 22 Picture Quality of All Connections from Ok to Best .................................... 24 Quick Installation -

X-74 Hdtv Digital Indoor Antenna

X-74 HDTV DIGITAL INDOOR ANTENNA INSTRUCTIONS This is a special designed antenna for digital TV broadcasting reception. It is the best solution for home reception and digital portable TV reception. The antenna is an active antenna that can be used with a TV or Set-top-box which supports coaxial cable powering, a power adapter is included. It can stand for vertical or horizontal mounting INCLUDED IN PACKAGE: Before you begin installation, please check contents: 1. Antenna main unit 2. AC/DC power adapter 1 2 3 3. Desktop standing supporter PRODUCT FEATURES: • SMD circuit technology design. • Shielded for minimum interference. • Built-in high gain and low noise amplifier. Amplifier Gain 28dB. • Horizontal or vertical positioning for best possible reception. • Stylish and compact size design with modern shiny black finish. • Powered by DTV set-top box or included separate power adapter. • Specially Compatible with HDTV of various digital terrestrial signals (DVB-T, ISDB-T, DMB-T/H, ATSC) and DAB/FM radios. • Increased VHF signal reception for foreign countries such as Mexico, South America and Russia. TECHNICAL DATA: Frequency range: VHF: 87.5-230MHz, UHF:470-862MHz Gain: 28dB Max Output level: 100dBμV Power Supply: Via separate AC/DC adapter (DC 6V/100mA) or via DTV set-top box(DC 5V/40mA) Impedance: 75Ω Noise Figure: ≤3dB Connector: F-male connector INSTALLATION: STEP 1: Connecting antenna to a tv with a digital tuner Attach the mini coax cable, which is the small black cable coming from the antenna. Simply screw the connector into the ANTENNA IN or CABLE IN port on the back of your television (See Fig. -

Federal Communications Commission DA 16-1333 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission DA 16-1333 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) ) EchoStar Technologies L.L.C. ) MB Docket No. 16-329 ) Hauppauge Computer Works, Inc. ) MB Docket No. 16-360 ) Petitions for Waiver of Section 15.117(b) of the ) Commission’s Rules ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: December 1, 2016 Released: December 1, 2016 By the Chief, Media Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. In this Order, we grant EchoStar Technologies L.L.C.’s (“EchoStar”) and Hauppauge Computer Works Inc.’s (“Hauppauge”) unopposed requests for waiver of Section 15.117(b) of our rules to allow EchoStar to import, market, and sell an Internet-enabled set-top box (the “AirTV”) and Hauppauge to import, market, and sell a USB component television tuner component product (the “WinTV-dualHD”). These devices, therefore, will not be required to include tuners that can receive analog broadcast signals.1 Section 15.117(b) of the Commission’s rules requires TV broadcast receivers to “be capable of adequately receiving all channels allocated by the Commission to the television broadcast service.”2 Pursuant to this provision, TV broadcast receivers must be capable of receiving both analog and digital broadcast signals until August 31, 2017.3 We conclude that waiver of this rule for the AirTV and WinTV-dualHD devices is in the public interest because waiver should enhance consumer choice for video equipment, offer consumers additional options for accessing video programming, and reduce cost and power consumption. II. BACKGROUND 2. The All Channel Receiver Act of 1962 grants the Commission the “authority to require that apparatus designed to receive television pictures broadcast simultaneously with sound be capable of adequately receiving all frequencies allocated by the Commission to television broadcasting when such 1 EchoStar Petition at 1. -

Rayzar® Air Amplified Local HD and Digital Broadcast TV Antenna

Rayzar® Air Amplified Local HD and Digital Broadcast TV Antenna Introducing the Rayzar Air, Winegard’s next generation in digital and HD broadcast TV antennas that deliver near Blu-Ray™ quality programming. With 60 years of unmatched antenna design and innovation, Winegard is once again leading the way in antenna technology with this ultra-sleek antenna that rivals our industry leading Sensar® antenna. Multi-directional - Optimized to receive UHF TV signals from both the front and back with a wide view of the antenna head capturing the full UHF spectrum. This doubles possible coverage area and makes it possible to receive more channels than ever before. Maximum UHF Reception - Unique element design provides superior UHF gain allowing greater reception from farther distances. Antenna also receives high band VHF reception. Ultra-thin and Sleek Design - Rayzar Air not only looks good, it is designed to withstand UV and harsh weather elements with the same proven durable housing used for Sensar antennas. In addition to getting the best HD signal, digital HD antennas continue to be a staple for RVers by providing the ability to watch live local broadcast programming. Tuning in to local news & weather is important to RVers and when the programming is FREE, the value is unmatched. Features and Benefits Multi-directional n Revolutionary antenna design provides multi-directional front/back TOWER 1 TOWER 2 coverage area for maximum channel reception in situations where broadcast towers are geographically spread apart. • Maximum UHF and high-band VHF reception n Antenna is very easy to tune in, requiring minimal aiming and/or re-pointing. -

No Logo说明书+FAQ20160326

Easy Set Up Instructions FAQ 5.Do I need an amplifier? be and often are different. Many stations have sub channels 15.What if I can not receive a signal with this antenna? N ote DIGITAL INDOOR TV ANTENNA If you live in area that is near the transmitter, there is no need to (channel 2, channel 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, etc.). Keep in mind reception Signal strength will vary based on certain variables. Such as Connect the end (F-male/IEC) of attached coaxial cable 1.Placing the antenna higher or close to/in ----FOR ULTRA THING SERIES---- 1.What is ATSC? boost the signal strength. If you live in a rural area where the will vary in your area due to environmental situation and distance from the transmitter, hills, buildings, and even tall 1 to the F-female/IEC external amplifier as shown. 4 A government mandate requires television broadcasters to signal is weak or intermittent, you may want to purchase location of the broadcast antenna. trees can impact reception. To check the exact distance from a window may result in better reception. convert from analog to digital broadcast. Now only digital amplifier kit to enhance your reception. your residence to the nearest transmitters, and get an idea of WHAT’S IN THE BOX signals are available over the air in US. Our antenna receive all 11.When do I need to run a channel scan? what to expect in the way of reception, go to antennapoint. You must rescan whenever you move Connect the other end F-female/IEC of the external 6.Can I add an extension cable to my antenna? Run a channel scan after setting up the antenna, then com or antennaweb.org and type in your zip code. -

Digital TV Service Guide Digital Conversion Boxes QAM Digital

Digital TV Service Guide The digital cable system requires a television with a QAM tuner. You must check the specifications from your TV manufacturer to determine if it includes the required tuner. The types of tuners currently in use in the United States are listed here for your reference. 1. QAM Tuner (REQUIRED) QAM (quadrature amplitude modulation) is the format by which digital cable channels are encoded and transmitted via cable television providers, including Apogee. A QAM tuner is the cable equivalent of an ATSC tuner which receives over-the-air digital channels broadcast by local television stations. Many new cable-ready digital televisions support both of these standards. Because there is no requirement, though, some very inexpensive manufacturers or models may not include the QAM tuner. Please be advised that less expensive TVs sometimes come with a lower quality QAM tuner that may be unable to tune all of the channels. We have found this to be true of bargain brands. If that is the case a digital conversion box can be purchased. 2. NTSC TUNER (NOT COMPATIBLE) 3. ATSC TUNER (NOT COMPATIBLE) Digital Conversion Boxes If your television does not have a QAM tuner, you can update your television or purchase a digital conversion box. Just like the TV, you should ensure that the conversion boxes include a QAM tuner and not just an ATSC tuner. Most tuner boxes available at electronic stores for over-the-air digital TV transition do not include a QAM tuner, be sure to verify the specifications from the external tuner manufacturer before completing your purchase.