Livestock Grazing Guidelines for Private Land Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Grazing.Pdf

MINNESOTA WETLAND RESTORATION GUIDE CONSERVATION GRAZING TECHNICAL GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Document No.: WRG 6A-5 Publication Date: 1/30/2014 Table of Contents Introduction Application Other Considerations Costs Additional References INTRODUCTION Grazing by bison, elk and deer was historically a natural occurrence in grassland and shrubland plant communities in Minnesota. This grazing tended to be nomadic in nature and its intensity depended on the type of grazers, herd sizes, climate conditions, fire frequency, and the composition and structure of individual plant communities. Today conservation grazing is conducted by a variety of species including cattle, bison, horses, sheep, and goats to target specific invasive plants, or to replicate the grassland plant community structure and diversity that historically resulted from grazing. When grazing is conducted to control invasive species the intensity and duration of grazing is carefully monitored to ensure that target species are managed effectively, and that the integrity of the plant community is maintained. Most conservation grazing involves a short pulse of grazing followed by a long rest. Grazing can have benefits as well as negative impacts, so it is important to involve experienced professionals. Detailed grazing plans are an important component in the planning and implementation of prescribed grazing. Equipment that may be needed for grazing includes watering systems, electric, or barb”ed” wire fences around rotational grazing areas, moveable fencing to concentrate grazing and to ensure that areas are not overgrazed, and in some cases salt licks to concentrate animals (Tu et al. 2001). The following is a list of species commonly used for conservation grazing and their general characteristics. -

Management of Grazing Animals for Environmental Quality

Management of grazing animals for environmental quality Etienne M. in Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67 2005 pages 225-235 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6600046 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ Etienne M. Management of grazing animals for environmental quality. In : Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products . Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 225-235 (Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://www.ciheam.org/ -

Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project Final Report

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project ATLAS ID GEF-00013971 TRAC-00013970 (formerly NEP/99/G35 and NEP/99/021) Final Report of the Terminal Evaluation Mission September 2006 Phillip Edwards (Team Leader) Rajendra Suwal Neeta Thapa ACRONYMS AND TERMS Exchange rate at the time of the TPE was US$1 to NR 71 (Nepali Rupees) ACA Anapurna Conservation Area ACAP Anapurna Conservation Area Project AHF American Himalayan Foundation APPA Appreciative Participatory Planning and Action BCP Biodiversity Conservation Plan CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAMOP Conservation Area Management Operation Plan CAMP Conservation Area Management Plan CAMR Conservation Area Management Regulation CBBMS Community Based Biodiversity Monitoring System CBO Community Based Organization CITES Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species CPM Co-Project Manager CRAC Community Resource Action Area Committee CRAJSC Community Resources Action Joint Sub-Committee CTF Community Trust Fund DAG Disadvantage Group DDC District Development Committee DNPWC Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation EIA Environment Impact Assessment FIT Free Independent Tourist/Trekker GEF Global Environment Facility GIS Geographic Information System GON Government of Nepal Ha. Hectares HMG His Majesty’s Government HQ Head Quarters HRD Human Resource Development ICDP Integrated Conservation Development Program ICIMOD International Center for Integrated Mountain Development IEA Initial Environmental Assessment IGA Income -

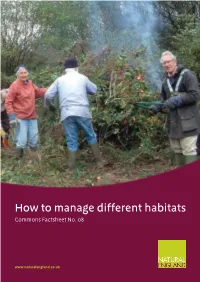

How to Manage Different Habitats Commons Factsheet No

How to manage different habitats Commons Factsheet No. 08 www.naturalengland.co.uk How to manage different habitats Many commons and greens are beautiful places, rich in wildlife. Because commons have a long history of being used by people, the habitats they support are relatively natural but have been shaped by human activities over the millennia (e.g. unimproved grassland, heathland, woodlands). If they are to retain their wildlife and scenery the traditional uses must either be continued, or replicated some other way (see FS3 Why does our common need to be looked after?). This factsheet summarises the characteristic features of each habitat type, together with conservation aims and management techniques for habitats frequently found on commons. Different techniques Before deciding on particular management techniques, you will want to consider their The management of habitats can vary from potential impact on the species present, simple to complex. It can often be carried the landscape, the environment, features out by volunteers with hand tools or may of archaeological and historical interest, need people with specialised training and and public access and safety (see FS5 Is our equipment. Here, the main methods you common more special than we think?, FS4 Who might use are outlined and sources of further has an interest in the common? and FS8 What information signposted. Herbicide treatments future for our commons?). Remember to plan are not discussed, as these are best used only aftercare and monitoring (see FS17 Are we if there are no other realistic options, and getting it right?). you will want specialist advice and possibly contractors to carry out the work. -

MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 Habitats * Semi-Natural Dry Grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210

Technical Report 2008 12/24 MANAGEMENT of Natura 2000 habitats * Semi-natural dry grasslands (Festuco- Brometalia) 6210 The European Commission (DG ENV B2) commissioned the Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites) This document was prepared in March 2008 by Barbara Calaciura and Oliviero Spinelli, Comunità Ambiente Comments, data or general information were generously provided by: Bruna Comino, ERSAF Regione Lombardia, Italy Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Mats O.G. Eriksson, MK Natur- och Miljökonsult HB, Sweden Monika Janisova, Institute of Botany of Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovak Republic) Stefano Armiraglio, Museo di Scienze Naturali di Brescia, Italy Stefano Picchi, Comunità Ambiente, Italy Guy Beaufoy, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Gwyn Jones, EFNCP - European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, UK Coordination: Concha Olmeda, ATECMA & Daniela Zaghi, Comunità Ambiente 2008 European Communities ISBN 978-92-79-08326-6 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Calaciura B & Spinelli O. 2008. Management of Natura 2000 habitats. 6210 Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates ( Festuco-Brometalia ) (*important orchid sites). European Commission This document, which has been prepared in the framework of a service contract (7030302/2006/453813/MAR/B2 "Natura 2000 preparatory actions: Management Models for Natura -

Bryn Tip Local Nature Reserve

BRYN TIP LOCAL NATURE RESERVE The village of Bryn is lucky enough to have its own Nature Reserve! The Reserve is popular with the residents of Bryn and visitors from further afield who come to walk their dogs, ride horses on the bridle way or take a gentle stroll whilst enjoying the wildlife and views of the surrounding countryside. The site has been used all year round and is also the starting point for the Bryn Heritage walk. This Reserve is home to hundreds of species of wildlife including flowers, fungi, invertebrates, birds, reptiles and mammals. The site was declared a Local Nature Reserve in order to protect the wildlife and preserve the landscape for people to enjoy long into the future. CONSERVATION GRAZING Over the last few years, the Countryside & Wildlife Team of the Local Authority have been working with contractors, and occasionally volunteers, to reduce the amount of invasive scrub on the site. This initial intensive management has allowed the grasses and flowering plants to flourish in those areas. However, unless the scrub is regularly managed it will become dense and eventually take over the grassland, making the site a lot less attractive to walk through. Similarly, the grassland is becoming rank and tussock and unless it is managed sensitively, much of the special wildlife will be lost. Using contractors and staff is not a sustainable long term approach for managing the Nature Reserve, even less so with the current and proposed budget cuts that the Local Authority is faced with. Conservation grazing is a more traditional, sustainable and less labour-intensive way of getting the grassland into good condition and keeping the scrub under control. -

2014 Transformations Program

SUNY College Cortland Digital Commons @ Cortland Transformations College Archives 2014 2014 Transformations Program State University of New York at Cortland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/transformationsprograms Recommended Citation State University of New York at Cortland, "2014 Transformations Program" (2014). Transformations. 25. https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/transformationsprograms/25 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Commons @ Cortland. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transformations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Cortland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSFORMATIONS A Student Research and Creativity Conference April 25, 2014 Portland Transformations: A Student Research and Creativity Conference April 25, 2014 Sperry Center SUNY Cortland Schedule of Events 12:30-1:20 p.m. Keynote Address Sperry Center, Room 105 "Multidisciplinary Solutions to 2T Century Environmental Challenges: Lessons from Sustainable Agriculture and Conservation Grazing" Gary S. Kleppel 73, Ph.D. Professor of Biological Sciences; Director of Biodiversity, Conservation & Policy Program University of Albany 1:30-2:30 p.m. Concurrent Sessions I 2:30-3 p.m. Poster Session A Sperry Center, 1st Floor Hallway 3-4 p.m. Concurrent Sessions II 4-4:30 p.m. Poster Session B Sperry Center, 1st Floor Hallway 4:30-5:30 p.m. Concurrent Sessions III Refreshments will be available 2:30-4:30 p.m. in Sperry Center, first floor food service area. PLEASE NOTE: Food and beverages are NOT allowed in classrooms. Cover design by Lauren Abbott, New Media Design major. Transformations: A Student Research and Creativity Conference is an event designed to highlight and encourage scholarship among SUNY Cortland students. -

Global Conservation Translocation Perspectives: 2021. Case Studies from Around the Globe

Global conservation Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 translocation perspectives: 2021 IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 Case studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group (CTSG) i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. IUCN is pleased to acknowledge the support of its Framework Partners who provide core funding: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland; Government of France and the French Development Agency (AFD); the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the United States Department of State. Published by: IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi & Calgary Zoo, Canada. Copyright: © 2021 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. -

Practical Grazing Management to Maintain Or Restore Riparian Functions and Values on Rangelands 1 2 3 Sherman Swanson , Sandra Wyman , and Carol Evans

Volume 2, 2015 pp. 1-28 ISSN: 2331-5512 Practical Grazing Management to Maintain or Restore Riparian Functions and Values on Rangelands 1 2 3 Sherman Swanson , Sandra Wyman , and Carol Evans Keywords: riparian vegetation, livestock grazing management, grazing strategies, grazing tools, stream, meadow, fish, wildlife habitat, water quality AGROVOC terms: controlled grazing, foraging, rangelands, riparian vegetation, riparian zones Abstract Successful rangeland management maintains or restores the ability of riparian plant communities to capture sediment and stabilize streambanks. Management actions are most effective when they are focused on the vegetated streambank closest to the active channel, the greenline, where vegetation most influences erosion, deposition, landform, and water quality. Effective grazing management plans balance grazing periods, especially those with more time for re-grazing, with opportunities for plant growth by adjusting grazing timing, duration, intensity, and/or variation of use and recovery. Emphasizing either: a) schedules of grazing and recovery, or b) limited utilization level within the same growing season, is a fundamental choice which drives management actions, grazing criteria, and methods for short-term monitoring. To meet resource objectives and allow riparian recovery, managers use many tools and practices that allow rather than impede recovery. Economic decisions are based on both evaluation of investments and ongoing or variable costs, themselves justified by reduced expenses, increased production, or improved resource values. Ongoing management adjusts actions using short-term monitoring focused on chosen strategies. Long-term monitoring refocuses management to target priority areas first for needed functions, and then for desired resource values. Once riparian functions are established, management enables further recovery and resilience and provides opportunities for a greater variety of grazing strategies. -

Lowland Raised Bogs

SCOTTISH INVERTEBRATE HABITAT MANAGEMENT Lowland raised bogs Wester Moss © Paul Kirkland / Butterfly Conservation Introduction Scottish records of the Bilberry pug moth (Pasiphila debiliata ) is from Kirkconnell Flow There has been a dramatic decline in the area of (Dumfries and Galloway) while the Bog sun- lowland raised bog habitat in the past 100 years. jumper spider ( Heliophanus dampfi ) is known The area of lowland raised bog in the UK only from two sites in the UK – one of which is retaining a largely undisturbed surface is Flanders Moss (Stirlingshire). In addition, there is estimated to have diminished by around 94% a possibility that the Bog chelifer ( Microbisium from an original 95,000 ha to 6,000 ha. In brevifemoratum ) is likely to occur in Scottish Scotland, it is estimated that the original 28,000 bogs—highlighting that there may yet be ha of lowland raised bog habitat has now unrecorded species in this important habitat diminished to a current 2,500 ha. Most of the (Legg, 2010). remaining lowland raised bog in Scotland is Support for management described in this located in the central and north-east lowlands. document is available through the Scotland Rural Historically the greatest decline has occurred Development Programme (SRDP) Rural through agricultural intensification, afforestation Development Contracts (RDC). A summary of and commercial peat extraction. Future decline is this support (at time of publication) can be found likely to be the result of the gradual desiccation of in this document. bogs, damaged by a range of drainage activities and/or a general lowering of groundwater tables. Lowland raised bogs support many rare and localised invertebrates, such as the Large heath butterfly (Coenonympha tullia ) and the 6 spotted pot beetle ( Cryptocephalus sexpunctatus ). -

Grazing Management

I. GRAZING MANAGEMENT The greatest diversity within California’s coastal grasslands can be seen in the forbs or wildflowers that BACKGROUND emerge in the spring following winter rains. Sites The vegetation of the Santa Cruz Mountains is comprised of a rich and with adequate management diverse assemblage of plant species. This wealth of diversity was most of non-native vegetation will evident within the grassland ecosystems that evolved under a variety of reward these efforts with disturbance pressures including fire and grazing by large herds of ungu- bountiful displays of colorful late animals, which are now mostly extinct. The flora that emerged has spring wildflowers. been described as one of the most diverse and species rich ecosystems in the United States. The arrival of early Spanish and Anglo settlers initiated a particularly dra- matic change in species composition of California grasslands, primarily as By some estimates, nearly a result of tilling the grasslands for agricultural crop production, reduction 80 percent of the vegetation of native grazing animals and introduction of cattle herds brought over cover within California from Europe and let loose on the new rangeland. This introduction of non- grasslands is exotic native plants and animals, coupled with the concurrent suppression of fire vegetation. on the landscape as the western United States was settled, resulted in the substantial replacement of the native grassland vegetation with a predom- inately exotic, annual flora. The exotic vegetation is often more competi- tive, productive, and prolific than the native plants within which it coexists, and tends to dominate and replace existing native grasses and wildflow- ers. -

Evaluating Treatments for Native Grassland Restoration 2013

Evaluating Treatments for Native Grassland Restoration 2013 Evaluating Treatments for Native Grassland Restoration Jonathan Haufler, Scott Yeats, and Carolyn Mehl Ecosystem Management Research Institute P.O. Box 717, Seeley Lake, MT 59868. www.emri.org Conservation Innovation Grant NRCS 69-3A75-9-152 Evaluating Treatments for Native Grassland Restoration 2013 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................. 1 Project Objectives ........................................................................................................ 3 Methods .......................................................................................................................... 3 Site Selection ............................................................................................................... 3 Treatments .................................................................................................................. 5 Prescribed Fire ......................................................................................................... 5 Prescribed Grazing .................................................................................................. 9 Prescribed Grazing and Prescribed Fire ................................................................ 14 Mechanical Shrub and Tree Removal ...................................................................