1 How Buddhist and Christian Liberation Epistemologies Should

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in International Buddhist Organizations by the Example of the Organization Rigpa

grant reference number: 01UL1823X The decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in international Buddhist Organizations by the example of the organization Rigpa Anne Iris Miriam Anders Globalization and commercialization of Buddhism: the organization Rigpa Rigpa is an international Buddhist organization (Vajrayāna Buddhism) with currently 130 centers and groups in 41 countries (see Buddhistische Religionsgemeinschaft Hamburg e.V. c/o Tibetisches Zentrum e.V., Nils Clausen, Hermann-Balk- Str. 106, 22147 Hamburg, Germany : "Rigpa hat mittlerweile mehr als 130 Zentren und Gruppen in 41 Ländern rund um die Welt." in https://brghamburg.de/rigpa-e-v/ date of retrieval: 5.11.2020) Rigpa in Austria: centers in Vienna and Salzburg see https://www.rigpa.de/zentren/daenemark-oesterreich-tschechien/ date of retrieval: 27.10.2020 Rigpa in Germany: 19 centers see https://www.rigpa.de/aktuelles/ date of retrieval: 19.11.2019 Background: globalization, commercialization and decontextualization of (Vajrayāna) Buddhism Impact: of decontextualization of terms and neologisms is the rationalization of economical, emotional and physical abuse of people (while a few others – mostly called 'inner circles' in context - draw their profits) 2 contents of the presentation I. timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa II. testimonies of probands from the organization Rigpa (in the research project TransTibMed) III. impact of decontextualizing concepts of Vajrayāna Buddhism and cross-group neologisms in international Buddhist organizations IV. additional citations in German language V. references 3 I) timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa 1. timeline of crucial events (starting 1994, 2017- summer 2018) (with links to the documents) 2. analysis of decontextualized concepts, corresponding key dynamics and neologisms 3. -

Looking, SEEING, LETTING BE, and BEING FREE

LooKING, SEEING, LETTING BE, AND BEING FREE ]-low oo I EXPERIENCE RIGPA? This question is really about how du alistic mind and mind essence actually are. When I teach, usually I first give the story of mind essence, offering a theory about how mind essence is so that you can get the idea intellectually. But it is quite possi ble that someone has already experienced the actuality of mind essence before hearing it explained intellectually; let's not rule out that possibil ity. Traditionally, first the theory is given, then the way or method of experiencing mind essence in actuality is taught. I haven't gotten to that point yet; we are still working on the intellectual picture. When I give this explanation, it's easy to make the mistake of think ing that mind essence is an entity somewhere inside dualistic mind. If we do this, we may gain some understanding of how mind essence is, but this understanding is within a dualistic framework-like the idea that within dualistic mind there is an empty essence, the idea that within dual istic mind we have a cognizant nature, and so forth. This is a conceptual understanding of the mind essence beyond concepts. Right now, from within our state of dualistic mind, we must actually experience how mind essence consists of essence, nature, and capacity. We try to approach how that mind essence actually is as an experience. That experience takes place by means of the pith instructions given by a master. Right here is the point where a qualified master would give the pointing-out instruction, directly pointing out the nature of mind. -

The Letter to Sogyal (Lakar)

July 14, 2017 Sogyal Lakar, The Rigpa Sangha is in crisis. Long-simmering issues with your behavior can no longer be ignored or denied. As long-time committed and devoted students we feel compelled to share our deep concern regarding your violent and abusive behavior. Your actions have hurt us individually, harmed our fellow sisters and brothers within Rigpa the organization, and by extension Buddhism in the West. We write to you following the advice of the Dalai Lama, in which he has said that students of Tibetan Buddhist lamas are obliged to communicate their concerns about their teacher: If one presents the teachings clearly, others benefit. But if someone is supposed to propagate the Dharma and their behavior is harmful, it is our responsibility to criticize this with a good motivation. This is constructive criticism, and you do not need to feel uncomfortable doing it. In “The Twenty Verses on the Bodhisattvas’ Vows,” it says that there is no fault in whatever action you engage in with pure motivation. Buddhist teachers who abuse sex, power, money, alcohol, or drugs, and who, when faced with legitimate complaints from their own students, do not correct their behavior, should be criticized openly and by name. This may embarrass them and cause them to regret and stop their abusive behavior. Exposing the negative allows space for the positive side to increase. When publicizing such misconduct, it should be made clear that such teachers have disregarded the Buddha’s advice. However, when making public the ethical misconduct of a Buddhist teacher, it is only fair to mention their good qualities as well. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

Taming the Poisonous: Mercury, Toxicity, and Safety in Tibetan

Chapter 4 History and Knowledge Transmission Tsodru chenmo is considered a secret practice going back to an early spiritual transmission to the Tibetan polymath Orgyen Rinchenpel, who brought it to Tibet in the thirteenth century. This chapter explores how ideas of taming and secrecy are embedded in the transmission of knowl- edge of mercury practices over time. How have these ideas affected the transfer of practical tsotel skills? Secrecy has led to specific ways of how Tibetan authors write about tsotel practices and how they publish and share texts, and understand its pastness. I explore these issues across the early history of mercury practices and then analyze how knowledge trans- mission of Sowa Rigpa mercury practices have changed in exile. I embed these aspects of Tibetan medical history in a discussion of where we can place the tsodru chenmo practice in the debate on medicine between sci- ence and religion (Adams, Schrempf, and Craig 2011b; Gyatso 2015). Situating mercury practices between science and religion As my earlier explorations of Sowa Rigpa and biomedical terminology of mercury processing have shown (Chapter 2), translating and understand- ing technical terms across different epistemologies is complex. Transla- tions between Sowa Rigpa medical epistemologies flow in multiple ways and are rarely straightforward (Adams, Schrempf, and Craig 2011a; Samuel 2006a). In this book I refer to epistemology within its broader meaning of how things are known, one way of which is through the empirical engage- ment of our senses.186 Adams, Schrempf, and Craig (2011b, 8) understand “sowa rigpa as an epistemology, [that] bears resemblance to Max Weber’s portrayal of modern science as ‘a vocation’.” In their view, rigpa (rig pa, the Tibetan term for ‘science’) “implies a different kind of engagement with knowledge than is typical for biomedical or Western forms of sci- ence precisely because it simultaneously suggests an experiential notion 186 Here, I follow other scholars who have worked on Sowa Rigpa. -

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster -

PDF of Buddhist Beliefs & Information

Buddhist Beliefs 1. Spiritual Belief: The Buddha did not deny the existence of higher beings, e.g. beings in the deva and brahma realms. However, these beings, according to the Buddha, are not to be regarded as one’s refuge or saviour. As recorded in the Dhammapada, an authoritative Buddhist text: Oneself, indeed, is one’s savior, for what other savior would there be? With oneself well controlled one obtains a savior difficult to find (Verse 160). By oneself, indeed, is evil done; by oneself is one defiled. By oneself is evil left undone; by oneself, indeed, is one purified. Purity and impurity depend on oneself. No one purifies another (Verse 165). These higher beings, like us, are subjected to birth, old age, sickness and death 2. How We Pray – House of worship, rituals and practices: Worship, prayers and rituals are generally conducted in the main hall before a Buddha image or statue in Buddhist temples and monasteries and are led by members of the monastic community. Some Buddhists prefer to conduct these practices in their homes before a Buddha image or statue. Buddhists generally chant verses of veneration to the Triple Gems – The Buddha, Dharma (Teachings) and Sangha (Community). In addition, Theravada practitioners chant the Discourse of Loving Kindness (Metta Sutta); Pure Land practitioners chant the Amitabha Sutra; Zen practitioners chant the Heart Sutra; and Vajrayana practitioners chant the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. Buddhists also offer food and other daily necessities to members of the monastic community in temples and monasteries and in turn the monks and nuns chant verses of blessings to the donors and sponsors. -

SBCS Newsletter Vol 59 Spring Summer 2017 Final

SBCS Newsletter 1! SPRING 2017 Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies Vol. 59 Spring 2017 News of the Society In this Newsletter Our Newsletter includes information that will appear later in Buddhist-Christian Studies: ▪ An overview of the 2016 Annual Meeting, including board and members meetings and panels ▪ Streng Award Announcement ▪ Reports on Conferences In this issue we also include: ▪ Information shared on upcoming events ▪ Announcement of a new journal ▪ Q&A on membership Concurrent with American Academy of Religions Annual Meeting ! ! San Antonio, TX, US November 18-19, 2016 The Annual Meeting of the Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies Sandra Costen Kunz SBCS Newsletter 2! SPRING 2017 • the board’s delight over how effectively newsletter editor Jonathan Seitz (in A pervasive background to this year’s annual Taipei) and treasurer Glenn Willis (in meeting was distress over the inaccuracy and Pennsylvania) were able to contribute to incivility of much of the discourse surrounding the its meeting via video conferencing – US presidential election – and the polarization and the implications of this success for fostered by such discourse. The society’s mission the increased involvement of can be seen, in part, as fostering discourse about international advisors, difference and common ground more honestly, happily, and hopefully – by “supporting activities • the board’s approval of University of related to the comparative study of, and the Hawai’i Press’ offer to make the journal practical interaction between, Buddhism and available -

Understanding Tibetan Religions Through Artistic Conventions

[TYPE THE COMPANY NAME] Field of Accumulation: A Trove of Questions Understanding Tibetan Religions Through Artistic Conventions Elizabeth Harris 3/22/2017 “I know all the details of karma, but I do not really believe in it. I have heard a lot of Dharma, but have never put it into practice. Bless me and evil-doers like me That our minds may mingle with the Dharma.” -Words of My Perfect Teacher Introduction The Tibetan plateau is home to a unique blended culture of the religions, Buddhism and Bön. Bön, otherwise known as The Nameless Religion, was the reigning religious practice of this area until the introduction of Buddhism in the seventh century A.D., which came to eventually dominate the entire plateau. The Buddhist take-over was not immediate by any means, and was further complicated by the acceptance of Bön beliefs and traditions into Buddhism. To this day there is still debate between whether or not Bön is still its own religion, or just a ‘newer’ sect of Tibetan Buddhism. “The Nyingma Lineage Refuge Field” dated 1800-1899, is a Buddhist scroll painting (thangka) depicting the distinct composition of a Field of Accumulation, also known as a Refuge Field. (Figure 1) This work represents the teachings of the Nyingma sect of Tibetan Buddhism and the lineage of the Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse; as described in the written guide by Patrul Rinpoche, Words of My Perfect Teacher. “Shenlha Odkar Tsog Shing” is a Bön scroll painting with a similar Refuge Field composition and is dated 1900- 1959. (Figure 2) The teachings represented here are described in a book by Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen’s Heart Drops of Dharmakaya; a guide to the Dzogchen practice of the Bön. -

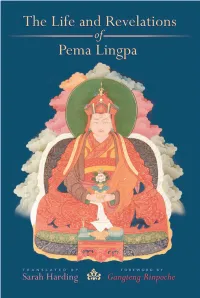

Pema Lingpa.Pdf

Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page i The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page ii Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iii The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa ሓ Translated by Sarah Harding Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york ✦ boulder, colorado Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iv Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2003 Sarah Harding All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. isbn 1-55939-194-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page v Contents Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche vii Translator’s Preface ix Introduction by Holly Gayley 1 1. Flowers of Faith: A Short Clarification of the Story of the Incarnations of Pema Lingpa by the Eighth Sungtrul Rinpoche 29 2. Refined Gold: The Dialogue of Princess Pemasal and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 51 3. The Dialogue of Princess Trompa Gyen and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 87 4. The Dialogue of Master Namkhai Nyingpo and Princess Dorje Tso, from Lama Jewel Ocean 99 5. The Heart of the Matter: The Guru’s Red Instructions to Mutik Tsenpo, from Lama Jewel Ocean 115 6. A Strand of Jewels: The History and Summary of Lama Jewel Ocean 121 Appendix A: Incarnations of the Pema Lingpa Tradition 137 Appendix B: Contents of Pema Lingpa’s Collection of Treasures 142 Notes 145 Bibliography 175 Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vi Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vii Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche his book is an important introduction to Buddhism and to the Tteachings of Guru Padmasambhava. -

The Dzogchen Path ~

~ The Dzogchen Path ~ Mingyur Rinpoche Dzogchen is called "Ati yoga" in Sanskrit and the “Great Perfection" in English. The Nine yanas encompass the complete practices of all of Buddhism. Including the Dzogchen tradition, practices are categorized into nine yanas that give a complete picture of the entire buddhadharma. Within the nine yanas, the highest one is Ati. The way that Ati yoga is structured, most of the teachings are categorized as the ground, path, and fruition. These are the three categories. The ground means the “principle” because the main focus of Dzogchen is the view. The view is the perspective or the principle, which is very important in Dzogchen. Before meditation, we have what we call "the ground." “The ground” means “who we are, who you are, who I am.” The fundamental nature of all of us is explained in the ground. I will teach you about the ground aspect of Dzogchen later. Now, I would like to focus on the Dzogchen path. In Dzogchen, normally there is not too much shamatha meditation. In Mahamudra, we have this step-by-step shamatha meditation practice. First, we look at how our minds relate to meditation and how we can free our minds. Next, experience comes, and then the next level of meditation. That is the Mahamudra style. In Dzogchen, there is not so much of this step-by-step shamatha practice. The main teaching of Dzogchen is what we call "trekchö," meaning "cutting through." In the teachings of trekchö, the first important thing is pointing out the nature of mind. Of course, we need to have a foundational practice before that. -

MARY FINNIGAN's PRESENTATION for the INFORM SEMINAR, JULY 2020 I'd LIKE to Thank Michelle for Speaking Direct, Stark Reality

MARY FINNIGAN’S PRESENTATION FOR THE INFORM SEMINAR, JULY 2020 I’D LIKE to thank Michelle for speaking direct, stark reality truth and for being one of the eight people whose open letter in July 2017 brought about Sogyal’s fall from grace. I first met Sogyal in the spring of 1973. Along with other people who shared my interest in meditation, I found him a place to teach – a house in Kilburn, London, which we squatted in the name of the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. I do not refer to Sogyal as Rinpoche. It is a title accorded to lamas in recognition of their contemplative realisation and scholarship. Sogyal was a charlatan who was never trained as a lama. But we did not know this in the 1970s. We were naïve, ill-informed, and enthusiastic. We felt lucky to be involved with a charismatic Tibetan guru, pictured left with The Dalai Lama on His Holiness’s first visit to London in 1973. It soon became obvious that our new-found teacher had an insatiable sexual appetite. He hit on virtually every pretty woman he encountered. It did not occur to us then that this behaviour was not compatible with the power imbalance inherent in his role as a lama. The late John Driver first sounded an alarm about Sogyal. John was a respected Tibetan Buddhist scholar-practitioner. I am a journalist, so after John’s alert, I applied my professional skills to finding out more about Sogyal’s background. His ascent into guru superstardom occurred after the publication of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, and his role in the movie Little Buddha.