The Lost World of Ended Summers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheet Music Unbound

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Sheet Music Unbound A fluid approach to sheet music display and annotation on a multi-touch screen Beverley Alice Laundry This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Waikato. July 2011 © 2011 Beverley Laundry Abstract In this thesis we present the design and prototype implementation of a Digital Music Stand that focuses on fluid music layout management and free-form digital ink annotation. An analysis of user constraints and available technology lead us to select a 21.5‖ multi-touch monitor as the preferred input and display device. This comfortably displays two A4 pages of music side by side with space for a control panel. The analysis also identified single handed input as a viable choice for musicians. Finger input was chosen to avoid the need for any additional input equipment. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

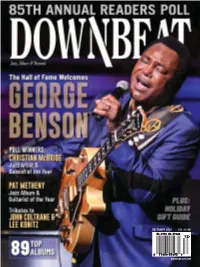

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Guardian, October 3, 1980

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 10-3-1980 The Guardian, October 3, 1980 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1980). The Guardian, October 3, 1980. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. October 3, 1980 Issue 14 VolumeXVII Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio Inside Carter : "No draft in Contractors cut powerline; University By BOB MYERS blacks out ' Guard lan Editor page 2 President jimmy Carter brought good news for 18 and 1? year old men with him to his '"town meeting" in Dayton yester- day: he sees no draft upcoming. Koch review "There is not going to be e draft imposed anytime in the foreseeable open hearings future." Carter said. "The only time a draft will be imposed is if our vital interests are threatened, start Oct. 13 • "I'm 'committed to the all volunteer Page 2 force. The registration for the draft does not lead to a draft." Carter, however,- also Bad some bad news. He said the Iranian-Iraq war could Soccer team threaten vital interests of the United States if.it lead to the closing of the Strait of defeats* Hormuz. THE STRAIT IS the only outlet from the Wittenburg Persian Gulf, through which most of the world's oil flows. -

Dark German Romanticism and the Postpunk Ethos of Joy Division, the Cure and Smashing Pumpkins

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Fall 2020 Dark German Romanticism and the Postpunk Ethos of Joy Division, The Cure and Smashing Pumpkins Logan Jansen Hunter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, L. J.(2020). Dark German Romanticism and the Postpunk Ethos of Joy Division, The Cure and Smashing Pumpkins. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/6182 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DARK GERMAN ROMANTICISM AND THE POSTPUNK ETHOS OF JOY DIVISION, THE CURE AND SMASHING PUMPKINS by Logan Jansen Hunter Bachelors in Arts University of South Carolina, 2017 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Nicholas Vazsonyi, Director of Thesis Yvonne Ivory, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Logan Jansen Hunter, 2020 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my Opa, who helped me to appreciate the complexities of music, understand the significance of history and inspire to learn the German language. Without him, this thesis would not have been possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Nicholas Vazsonyi for his willingness to direct my thesis. I would also like to thank Will Whisenant, Ross and James Haynes, Max Gindorf, and C.J. -

National Press Club Luncheon with Leonard Slatkin, Music Director, National Symphony Orchestra Moderator: Theresa Werner, Ap

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH LEONARD SLATKIN, MUSIC DIRECTOR, NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA MODERATOR: THERESA WERNER, AP BROADCAST LOCATION: THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: FRIDAY, MAY 9, 2008 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MS. WERNER: Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club for our speaker luncheon featuring Leonard Slatkin. My name is Theresa Werner of AP Broadcast and a member of the National Press Club Board of Governors. I'd like to welcome club members and their guests in the audience today, as well as those of you watching on C-SPAN. We're looking forward to today's speech. And afterwards, I will ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech, so that we have time for as many questions as possible. For our broadcast audience, I'd like to explain that if you hear applause, it may be from the guests and members of the general public who attend our luncheons, and not necessarily from the working press. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

12 Years of Recording Dwight Yoakam, Dusty Wakeman 6/16/10 9:39 AM

12 Years Of Recording Dwight Yoakam, Dusty Wakeman 6/16/10 9:39 AM 12 Years Of Recording Dwight Yoakam Dusty Wakeman email print ShareThis rss Ron told me of plans to record a country and cowpunk compilation and asked if I wanted to be the engineer, which, being Texas born-n- bred, I jumped on. Pete Anderson walked in the door and we really hit it off. Dwight was in the process of getting signed and had already released the EP version of Guitars . ., which was creating quite a buzz. They were opening for bands like X, Los Lobos, and The Blasters, and really connecting with those crowds. The plan was to go in and cut four more tracks to complete the album. There was some controversy with the label — Warner Nashville — who wanted Dwight to go to Nashville and work with “the establishment” there. There have been scores of great records recorded there that we all love, but this was the tail end of the Urban Cowboy era, and most everything coming out of Nashville at that moment was pretty wimpy and formulaic. Pete liked me because I was coming from a rock background but knew and loved classic country. He had Dwight drop by Mad Dog to meet me while working on Town South of Bakersfield. I remember Dwight and Pete looking at the 2-track and being impressed with how hot the recording levels were. GUITARS, CADILLACS, ETC. ETC. We were booked into Capitol Studio B for something like three days, as I recall, to cut four tracks: “Honky Tonk Man,” “Guitars, Cadillacs,” “Bury Me” (a duet with Maria McKee), and “Heartaches by the Number.” We were like kids in a candy store — we kept waiting for some adult to come and stop the fun. -

TOWNSHIP of PEMBERTON REGULAR MEETING October 2, 2019 6:00 P.M. FLAG SALUTE Council President Trueblood Led the Assembly In

TOWNSHIP OF PEMBERTON REGULAR MEETING October 2, 2019 6:00 P.M. FLAG SALUTE Council President Trueblood led the assembly in the Pledge of Allegiance, announced that notice of the meeting was given in accordance with the Open Public Meetings Act, and followed by roll call. ROLL CALL PRESENT ABSENT Elisabeth McCartney Jason Allen Donovan Gardner Gaye Burton Norma Trueblood Also, present: Mayor David Patriarca, Business Administrator Daniel Hornickel, Solicitor Andrew Bayer and Township Clerk, Amy P. Cosnoski. CALL TO ORDER Council President Trueblood called the meeting to order at approximately 6:00 p.m. CLOSED SESSION 233-2019 Authorizes Council to go into Closed Session – Not Adopted Mr. Hornickel advised that it was his intention to discuss the PTMUA employees. Advised that he had asked Mrs. Cosnoski to send RICE notices to all of the PTMUA workers who responded that they would like to have their Personnel discussion held in open session and he is comfortable doing this. Commented that he will reserve doing this until it is the appropriate time. PRESENTATIONS 2019 Fire Prevention Proclamations Council President Trueblood read the Resolution aloud. It was noted that there were no representatives from the Fire Department present at the meeting. Mayor Patriarca advised that the content of his Proclamation was pretty much the same as the Council Resolution. Noted that our volunteers have been working harder than ever responding to calls. Stated he did not have actual numbers but knows that the last time he spoke to the Chief the numbers were up. Asked all to keep in mind that they are all volunteers and are not getting paid to do what they are doing. -

Musical News July

Carol Panofsky, Oboe: Making Music Her Way Musical News pg 4 July - August 2017 | Vol. 89, No. 4 The Evolution Of A Committee Member Revisited by David Schoenbrun, President I don’t often enough publicly rain praise While I am sure there are those noble with their tunnel-vision attitudes, on the many orchestra committee members folks among us, I’ve concluded that but rather the modeling that they are who work tirelessly on behalf of their they are the rare exception. Self- exposed to – sometimes for hours at colleagues. The Union and its CBA service, by and large, is the initial a time – during which they see and groups depend upon their efforts to ensure draw for musicians to serve on absorb how colleagues are able to good the negotiation of good contracts and committees, especially negotiating put aside propensities to “take care In This Issue. their day-to-day administration. Hence committees. But almost invariably of #1” in favor of communal thought my reprise of this article first published the self-serving motivations of new and action. The long-term benefits David Schoenbrun Article in July 2009… have a wonderful, restful committee members loosens and of winning the war versus the battle Beth Zare Article summer! broadens over time into something become apparent. The pressures Election Notice much greater. subtly exerted by the group to have Picnic Announcement The Evolution of a Committee each member join in concerted Member collective action – the definition of New & Reinstated Members Unionism – eventually becomes Address Changes One of the things I enjoy most irresistible. -

II I I WEEKLY Volume 53 No

:4 III;I iWEEKLY Volume$2.80June$3.00 plus 1,53 .201991 No. GST 26 2 - RPM - June 1, 1991 Countrysponsored.CountryFor the first Awards, Toronto's time59 theinsponsors newest theawards history AM dinner country of Big the will radio Big beCountrywhensonRothschild were first dinner enthusiasticapproached and Program andabout Director promptly the sponsorship Bill laid Ander- plans andLayreceivedand theforotherKlees Sundayboth from KEY was the John Radio awardsVarietyalso Thompson pleased executives. show. Salute with of to Hostess/FritoBig the Countrysupport Castlethedinner.station, HarbourStan Westin. The Country Klees, gala, Ballroom co-founder59,industry is sponsoring of affair Toronto's of the is beingBig the Harbour Countryawards held in forCountrychain.to involve theOn Variety -air59's other sisterpersonalities Club stations stations Salute in fromwill Tothe beBig KEY severalin Country Toronto Radioof Publisher,FranksignCapek Davies, publishing has - TMP/MCAPresidentannounced of the agreementTMP signing - TheMusic of Music John 7pricesAwards,todifficult. pecent $107.00." down GST, pointedThe to onlywhich last out added year'sbrought that cost "keeping $100.00 the this ticket year thewas pricewas ticket very theup (afternoons)BrownAwardsluncheonCKGL from Kitchener'spresentations. (May from CHF 24) CKBY-FMX andRandy Halifax, Thesefor Owens,theOttawa andinclude Big Dorothy Country Alan composer,jointpublishingCapek venture to an deal songwriter,company. "exclusive" with the Capek TMP/MCA keyboardistNorth is a wellAmerican Musicknownand -

Dwight Yoakam

2008 Induction Class Dwight Yoakam With his stripped-down approach to traditional honky tonk and Bakersfield country, Dwight Yoakam helped return country music to its roots in the late '80s. Like his idols Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, and Hank Williams, Yoakam never played by Nashville's roots; consequently, he never dominated the charts like his contemporary Randy Travis. Then again, Travis never played around with the sound and style of country music like Yoakam. On each of his records, he twists around the form enough to make it seem like he doesn't respect all of country's traditions. Appropriately, his core audience was composed mainly of roots rock and rock & roll fans, not the mainstream country audience. Nevertheless, he was frequently able to chart in the country Top Ten, and he remained one of the most respected and adventurous recording country artists well into the '90s. Born in Kentucky but raised in Ohio, Yoakam learned how to play guitar at the age of six. As a child, he listened to his mother's record collection, honing in on the traditional country of Hank Williams and Johnny Cash, as well as the Bakersfield honky tonk of Buck Owens. When he was in high school, Yoakam played with a variety of bands, playing everything from country to rock & roll. After completing high school, Yoakam briefly attended Ohio State University, but he dropped out and moved to Nashville in the late '70s with the intent of becoming a recording artist. At the time he moved to Nashville, the town was in the throes of the pop-oriented urban cowboy movement and had no interested in his updated honky tonk.