Dwight D. Murray, Esquire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wake Forest Offense

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2005 12 FOR BASKETBALL EVERYWHERE ENTHUSIASTS FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE ASSIST FABRIZIO FRATES SKIP PROSSER - DINO GAUDIO THE OFFENSIVE FUNDAMENTALS: the SPACING AND RHYTHM OF PLAY JONAS KAZLAUSKAS SCOUTING THE 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES WAKE FOREST paT ROSENOW THREE-PERSON OFFICIATING LARS NORDMALM OFFENSE CHALLENGES AT THE FIBA EUROBASKET 2003 TONY WARD REDUCING THE RISK OF RE-INJURY EDITORIAL Women’s basketball in africa is moving up The Athens Olympics were remarkable in many Women's sport in Africa needs further sup- ways. One moment in Olympic history deserves port on every level. It is not only the often special attention, especially as it almost got mentioned lack of financial resources and unnoticed during the many sensational perfor- facilities which makes it difficult to run proper mances during the Games - the women's classi- development programs. The traditional role of fication game for the 12th place. When the women in society and certain religious norms women's team from Nigeria celebrated a 68-64 can create further burdens. Saying that, it is win over Korea after coming back from a 18 - 30 obvious that the popularity of the game is margin midway through the second period, this high and Africa's basketball is full of talent. It marked the first ever African victory of a is our duty to encourage young female women's team in Olympic history. This is even players to play basketball and give them the the more remarkable, as it was only the 3rd opportunity to compete on the highest level. appearance of an African team in the Olympics against a world class team that was playing for The FIBA U19 Women’s World Championship Bronze just 4 years ago in Sydney. -

Fire Victims Share Ideas on Donations

NEW SPEAKER SHI’ITE COMES HOME BEARCATS SLIP LEADS HOUSE CLERIC WHO FOUGHT U.S. RETURNS TO IRAQ FROM EXILE PAST KNIGHTS NATION PAGE 6 WORLD PAGE 28 SPORTS PAGE 11 Thursday • Jan.6,2011 • Vol XI,Edition 122 www.smdailyjournal.com Mayor: Old Town ‘not’ a lost cause South City grapples with aftermath of triple homicide By Bill Silverfarb an alleyway off Linden Avenue in a Councilman Pedro Gonzalez, a 45- DAILY JOURNAL STAFF gang-related shooting that also left three year resident of Old Town, was at the others injured. crime scene Dec. 22 as he lives just a As friends and family of Hector Flores Since the killings, South San block away from the site of the triple gathered at his funeral yesterday after- Francisco Mayor Kevin Mullin and homicide. “It is time for parents to speak up,” noon to pay final respects to one of three other city officials have reached out to neighborhood residents to solicit assis- Gonzalez said. homicide victims in South San tance for a problem that cannot be It will take schools, nonprofit agen- Francisco Dec. 22, police are frantically solved by police alone. cies, police and leaders from within Old searching for his killer and city officials “This will take an entire community Town itself to come together to address are strategizing on how to bring calm to effort,” Mullin said. “We have to provide the gang activity, high dropout rates, a neighborhood that suffered five mur- vision for people in that neighborhood absentee landlords and teen pregnancy BILL SILVERFARB/DAILY JOURNAL ders in 2010. -

Sheet Music Unbound

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Sheet Music Unbound A fluid approach to sheet music display and annotation on a multi-touch screen Beverley Alice Laundry This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Waikato. July 2011 © 2011 Beverley Laundry Abstract In this thesis we present the design and prototype implementation of a Digital Music Stand that focuses on fluid music layout management and free-form digital ink annotation. An analysis of user constraints and available technology lead us to select a 21.5‖ multi-touch monitor as the preferred input and display device. This comfortably displays two A4 pages of music side by side with space for a control panel. The analysis also identified single handed input as a viable choice for musicians. Finger input was chosen to avoid the need for any additional input equipment. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

2010-11 Preview Birmingham-Southern College Panthers

Past SCAC Champions Year School Conf. Overall Coach 1991-92 Centre College 11-1 17-9 Cindy Noble-Hauserman 1992-93 Centre College 14-0 19-6 Cindy Noble-Hauserman 1993-94 Centre College 12-2 18-7 Cindy Noble-Hauserman 1994-95 Trinity University 12-2 19-6 Becky Geyer 1995-96 # Millsaps College 12-2 23-4 Cindy Hannon # Hendrix College 12-2 21-5 Chuck Winkelman 1996-97 Hendrix College 14-0 23-4 Chuck Winkelman 1997-98 Southwestern University 12-2 15-11 Ronda Seagraves 1998-99 DePauw University 18-0 22-5 Kris Huffman 1999-00 # DePauw University 15-3 20-5 Kris Huffman # Hendrix College 15-3 22-5 Chuck Winkelman 2000-01 #Centre College 14-4 22-6 Jennifer Ruff # DePauw University 14-4 19-6 Kris Huffman # University of the South 14-4 18-7 Richard Barron 2001-02 DePauw University 17-1 26-4 Kris Huffman 2002-03 ^ Trinity University 13-1 28-5 Becky Geyer 2003-04 DePauw University 13-1 26-4 Kris Huffman 2004-05 Trinity University 11-3 25-5 Becky Geyer 2005-06 DePauw University 14-0 29-2 Kris Huffman 2006-07 ^ DePauw University 12-2 31-3 Kris Huffman 2007-08 DePauw University 14-0 28-4 Kris Huffman 2008-09 Oglethorpe University 12-2 27-4 Ron Sattele 2009-10 DePauw University 15-1 26-4 Kris Hufman # - Denotes SCAC Co-Champion ^ - Denoted National Champion 2002-03 First year of SCAC Tournament to determine Automatic Qualifier for the NCAA Tournament Southern Collegiate Athletic Conference Commissioner: Dwayne Hanberry Director of Sports Information: Jeff DeBaldo Director of Communications and New Media: Russell Kramer SCAC Women’s Basketball Media Relations Contact: Russell Kramer [email protected] (678) 546-3470 (W) (678) 315-0379 (C) (678) 546-3471 (Fax) 2940 Horizon Park Drive – Suite D Suwanee, GA 30024-7229 www.scacsports.com SUWANEE, Ga. -

Water Panel to Discuss the Quality of Iowan Water,Urban Education Symposium Addresses Impacts of Inequality,College Faces Ongoin

Water Panel to discuss the quality of Iowan water By Kelly Page [email protected] This Sunday, Feb. 25 at 2 p.m., Bucksbaum 152 will host a panel discussion entitled “Where Does Our Water Come From & Where Does It Go? A Look at Water in Grinnell and Poweshiek County.” Coming shortly after the passage of a $282 million water quality bill in the Iowa legislature in late January, which aims to reduce nitrogen and phosphorous in Iowa water, this discussion is extremely timely and will offer a chance for Grinnellians to ask experts on local water about how state wide water-related patterns play out on a local level. There are many issues with water in Grinnell that may provide discussion points on Sunday. In Iowa, runoff from farming cause chemicals like nitrates to seep into water supplies. Additionally, in 2016 the Iowa Department of Natural Resources found that upwards of 6,000 Iowans may have been exposed to unsafe levels of lead in their drinking water. Although Grinnell was not one of the affected communities, many Grinnellians probably want to know for sure just how safe the town’s drinking water is. The water quality report on the City of Grinnell’s website has not been updated since 2016, when Grinnell’s drinking water did not violate federal contamination limits. Professor Peter Jacobson, biology, who will moderate the discussion, said, “At the national level people hear about Flint, Michigan and other areas where water quality is a significant issue, so folks may want to know how safe Grinnell’s tap water is.” Interestingly, -

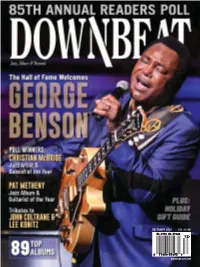

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Grinnell Magazine Summer 2015

The Grinnell Magazine Summer 2015 The Most Precious G Commodity on Earth Student Musings Exploring a Career Second-year student reflects on her spring break externship. At 12, I wanted to become a mathematician. At 16, I Larissa Stalcup, and Adrienne Squier all studied studied English to become a diplomat. Now, at 19, I marketing but they now have different specializations: strive to do marketing. Sarah coordinates the website, Larissa is a graphic It’s good to know what you like, isn’t it? But here designer, and Adrienne manages all social media is the fact: You don’t marry all of your crushes. You platforms. Talking with them broadened my perspectives marry someone you like, who likes you back, and whose on possible options in a marketing career and gave me lifestyle matches yours. Likewise, not all interests can some guidelines about how I can prepare myself for become your future career. Whether in relationships or a each approach. Larissa introduced me to some design career, we all need a dating phase. And dating is fun! software and showed me how to study it by myself. One way Grinnell offers “career dating” is through Adrienne shared some cool media tips and how to its spring break job shadows, which it calls externships. quantitatively measure the effectiveness of media Externships last three to five days and are offered by strategies. Grinnell alumni throughout the United States. Many Sarah says: “Even though I’m in charge of studying include a home stay with the alum too. Web behaviors and brainstorming ideas, I still need to So I scanned through the list of spring 2015 have some technical knowledge to know what is possible externship possibilities with the keyword “marketing.” and what is not.” Taking her advice, I plan to take Trang Nguyen ’17 I was quite surprised to come across an externship in more computer science classes even though I’m more is a math major Grinnell College’s Office of Communications because interested in the strategy part. -

The Grinnell System

THE SYSTEM— THE METHOD BEHIND THE MADNESS CREATION OF THE SYSTEM The QUESTIONS The ANSWERS The COMPONENTS of the System The FORMULA for Success (Stat Goals) THE KEY QUESTIONS How can we score as many points as possible? How can I get as much out of as many players as possible? How can I have more fun coaching and lower my stress level? How can I foster better team chemistry/relationships? How can we maximize our scoring? Conventional BBall: ―Get Better Shots‖ Run & Gun BBall: ―Get MORE Shots‖ and… ―Shoot MORE Threes‖ So, if getting more shots is essential to maximize scoring… HOW can we get more shots? Three Ways to Get MORE Shots 1. Increase the Pace of Play 2. Force More Turnovers 3. Get More Second Shots Getting more shots by… Increasing Pace of Play Fast Break—ALL THE TIME Press—ALL THE TIME Give ―Green-light‖ to Shooters Teach LESS patience offensively Teach 12 second shot goal Interesting Result: Your TO% goes down! – Players shoot BEFORE they turn it over! (Less time for TO) – The ball is in best BH hands most of the time Getting more shots by Forcing More Turnovers Press (i.e. Trap) ALL THE TIME… …after MADE shots …after MISSED shots …after DEAD BALLS (FC, Side, Underneath) …and even in FRONT COURT! Getting more shots by… Generating More Second Shots Send FOUR to the boards Shoot more 3’s (longer RB’s) Shoot more in Transition (harder to box out) Getting more shots via… THE HUMAN FACTOR: Units and Playing Shifts MAX effort needed to make press work. -

The Guardian, October 3, 1980

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 10-3-1980 The Guardian, October 3, 1980 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1980). The Guardian, October 3, 1980. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. October 3, 1980 Issue 14 VolumeXVII Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio Inside Carter : "No draft in Contractors cut powerline; University By BOB MYERS blacks out ' Guard lan Editor page 2 President jimmy Carter brought good news for 18 and 1? year old men with him to his '"town meeting" in Dayton yester- day: he sees no draft upcoming. Koch review "There is not going to be e draft imposed anytime in the foreseeable open hearings future." Carter said. "The only time a draft will be imposed is if our vital interests are threatened, start Oct. 13 • "I'm 'committed to the all volunteer Page 2 force. The registration for the draft does not lead to a draft." Carter, however,- also Bad some bad news. He said the Iranian-Iraq war could Soccer team threaten vital interests of the United States if.it lead to the closing of the Strait of defeats* Hormuz. THE STRAIT IS the only outlet from the Wittenburg Persian Gulf, through which most of the world's oil flows. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION If you’re interested in Coaching the System, you’re probably desperate. Or crazy. Or both. A normal human being wouldn’t even consider running the System, right? But what you know about it intrigues you, and you’re hopeful this book will be a good resource. Maybe you are searching to find a different approach, anything that will help your team improve, or that might be a better fit for your personnel next year than whatever it is you’ve been doing. And you’re desperate enough to try anything, even something as crazy—or “chaotic,” as we prefer to think of it—as The System. On the other hand, you might be a coach who has run some version of this extreme up-tempo style, and want to learn more details, deepen you knowledge base, or pick up a few new wrinkles that will give your team an edge. You love the approach, have used it for a few years, and already own a good library of instructional videos related to System basketball. Regardless of your category (desperate, crazy, or normal), we wrote this book with you in mind. We are pretty sure you aren’t picking it up as casual beach reading material, so we’re writing a technical book that tries to answer a lot of the same questions we had when we were starting out. It is—intentionally—fairly detailed, which might lead you to believe the System is complicated. It is not. In fact, a refrain you will encounter frequently in these pages is “Less is more.” SOME IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS So let’s start by making a few points. -

The Lost World of Ended Summers

The Lost World of Ended Summers They’re at the far side of the lake on separate slabs of granite sloping into the water. Between them, wedged in crevices amid ferns and grass is an array of empty beer bottles. Another six- pack bobs in the water below in a cooler tied to their canoe’s bowsprit. The lake is a smear of brilliance returning the flat blue and white of the sky with flashes of brown-black toward its center. On the drive out, she told him how it is the deepest body of water in the region, hundreds of feet at its northern end, and how in the 1920’s a logging village thrived at its depths. Now it’s just the two of them and the faint lapping of water on stone, the obliterating weight of sun and heat made all the more oppressive by the density of woods and brambles growing right to the edges of the rock behind them, hemming them in—no trail, no road, no clearance and nowhere to escape the sun. He rubs his hands together to wipe away the dust and grit of granite dimpling his palms; shakes out his left hand to ease the cramping through his wrists. Changes position again so his legs don’t fall asleep. “Another?” he asks, and tips upright. He stretches and looks around for the umpteenth time for any shade or cover, anywhere to escape the sun. “Some of those chips too, if you don’t mind, yes please.” At the edge of the water he stands a moment peering into his shadow beside their canoe.