San Diego History Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Topps Transcendent Tennis Checklist Hall of Fame

TRANSCENDENT ICONS 1 Rod Laver 2 Marat Safin 3 Roger Federer 4 Li Na 5 Jim Courier 6 Andre Agassi 7 David Hall 8 Kim Clijsters 9 Stan Smith 10 Jimmy Connors 11 Amélie Mauresmo 12 Martina Hingis 13 Ivan Lendl 14 Pete Sampras 15 Gustavo Kuerten 16 Stefan Edberg 17 Boris Becker 18 Roy Emerson 19 Yevgeny Kafelnikov 20 Chris Evert 21 Ion Tiriac 22 Charlie Pasarell 23 Michael Stich 24 Manuel Orantes 25 Martina Navratilova 26 Justine Henin 27 Françoise Dürr 28 Cliff Drysdale 29 Yannick Noah 30 Helena Suková 31 Pam Shriver 32 Naomi Osaka 33 Dennis Ralston 34 Michael Chang 35 Mark Woodforde 36 Rosie Casals 37 Virginia Wade 38 Björn Borg 39 Margaret Smith Court 40 Tracy Austin 41 Nancy Richey 42 Nick Bollettieri 43 John Newcombe 44 Gigi Fernández 45 Billie Jean King 46 Pat Rafter 47 Fred Stolle 48 Natasha Zvereva 49 Jan Kodeš 50 Steffi Graf TRANSCENDENT COLLECTION AUTOGRAPHS TCA-AA Andre Agassi TCA-AM Amélie Mauresmo TCA-BB Boris Becker TCA-BBO Björn Borg TCA-BJK Billie Jean King TCA-CD Cliff Drysdale TCA-CE Chris Evert TCA-CP Charlie Pasarell TCA-DH David Hall TCA-DR Dennis Ralston TCA-EG Evonne Goolagong TCA-FD Françoise Dürr TCA-FS Fred Stolle TCA-GF Gigi Fernández TCA-GK Gustavo Kuerten TCA-HS Helena Suková TCA-IL Ivan Lendl TCA-JCO Jim Courier TCA-JH Justine Henin TCA-JIC Jimmy Connors TCA-JK Jan Kodeš TCA-JNE John Newcombe TCA-KC Kim Clijsters TCA-KR Ken Rosewall TCA-LN Li Na TCA-MC Michael Chang TCA-MH Martina Hingis TCA-MN Martina Navratilova TCA-MO Manuel Orantes TCA-MS Michael Stich TCA-MSA Marat Safin TCA-MSC Margaret Smith Court TCA-MW -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

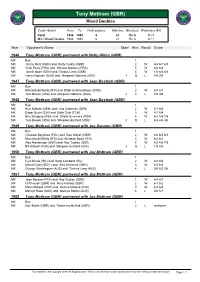

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles Code->Event From To Participations Matches Won/Lost Walkovers W/L Total 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 MX->Mixed Doubles 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 Year Opponent's Name Seed Rnd Result Score 1946 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Betty Hilton (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Jimmy Hunt (GBR) and Betty Coutts (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/1 6/3 MX Yvon Petra (FRA) and Simone Mathieu (FRA) 3 W 6/4 6/3 MX Jannik Ipsen (DEN) and Gladys Lines (GBR) 4 W 1/6 6/3 6/4 MX Harry Hopman (AUS) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 1 Q L 4/6 2/6 1947 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Bibbi Gullbrandsson (SWE) 2 W 6/3 6/1 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 2 3 L 0/6 3/6 1948 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Kurt Nielsen (DEN) and Lisa Andersen (DEN) 2 W 6/1 6/3 MX Edgar Buchi (SUI) and Edith Sutz (TCH) 3 W 6/1 6/4 MX Eric Sturgess (RSA) and Sheila Summers (RSA) 4 W 6/2 1/6 7/5 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 6/4 4/6 3/6 1949 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Gannon (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Czeslaw Spychala (POL) and Bea Walter (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/3 6/3 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Annelise Bossi (ITA) 3 W 6/2 6/2 MX Alex Hamburger (GBR) and Kay Tuckey (GBR) 4 W 6/2 4/6 7/5 MX Bill Sidwell (AUS) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 1/6 4/6 1950 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Mottram (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Cyril Kemp (IRL) and Betty Lombard (IRL) 2 W 6/2 6/4 MX Marcel Coen (EGY) and Alex McKelvie (GBR) 3 W 6/3 6/4 MX George Worthington (AUS) and -

Meet the Summer Camp Staff 2015 "Experience Is the Best Teacher!"

Meet The Summer Camp Staff 2015 "Experience is the best teacher!" Gary Engelbrecht Chris Ayer SOME FUN FACTS ABOUT Camp Director Basketball/Swim • SOME OF OUR • Head Pro and NBA D-League Profes- Director of Tennis sional for the world NEWEST COACHES. at TRFC for 34 champion Miami Heat Tennis Pro Lamine Bangoura at- years • McDonalds High school tended the world famous Bollettieri • Gary worked with All-American at Amphi Tennis Academy and was roommates • more than 30 Played College Division with Pete Sampras! He was also the #1 nationally ranked I Basketball for Loyola Junior Tennis player Marymount University players, 20 Southwest Champions, and more In Africa. Tennis than 50 AZ State High School Champs. • Played on the Loyola water polo team coaches Tatum • Worked for “Hall of Fame” coaches Nick Bollet- Rochin and Alan tieri and Harry Hopman. Brian Ramirez Barrios played Di- • University of Arizona Women’s Tennis Assis- Tennis Pro • vision I tennis for tant (6 years) including “Final Four” appear- U of A Women's Tennis Assistant Coach. ance and PAC 10 Championship. • Stanford Women's Tennis Assistant Coach. Northern Arizona • Tennis Coach Tatum Nike Tennis Camp Assistant Director in Stan- University. All Rochin played D1 tennis in college! Sam Ciulla ford. sports coach Kailey Camp Director • Brian has been with the Tucson Racquet Club Mellen has a soft- • Associate Head Tennis Pro at Tuc- for 6 years. ball scholarship at Coastal Carolina • son Racquet Club for 34 years. Brian is the proud parent of his 11 month old University. Soccer star Raymond son Parker. -

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park Equestrian Facilities Project Historic Land Use Study and Analysis

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park Equestrian Facilities Project Historic Land Use Study and Analysis Prepared by: Alexander D. Bevil, Historian II California State Parks, Southern Service Center 28 January 2010 Table of Contents Purpose .............................................................................................................................1 Descanso Area Development ...........................................................................................1 Descanso: Early History ............................................................................................1 Early Exploration Period ............................................................................................1 Mexican Rancho Period .............................................................................................2 American Homesteading/Ranching Period ................................................................3 Road Development .....................................................................................................4 Descanso Area Development as a Mountain Resort ..................................................5 Allen T. Hawley Ranch ..............................................................................................6 The Oliver Ranch .......................................................................................................7 Oliver Ranch Improvements ....................................................................................10 Historic Resources Summary ...................................................................................12 -

Historical Resources Board

THE CITY OF SAN DIEGO Historical Resources Board DATE ISSUED: November 7, 2003 REPORT NO. P-03-348 ATTENTION: Historical Resources Board Agenda of November 21 , 2003 SUBJECT: ITEM 6 - Historic Resources Inventory Update of The Centre City Core APPLICANT: City Centre Development Corporation LOCATION: Various addresses within the Centre City Core survey area, generally bounded by Union Street, A Street, Twelfth A venue, E Street east of Sixth A venue and Broadway west of Sixth A venue, Centre City, Council District 8 DESCRIPTION: Consider the designation of 37 sites within the Centre City Core area as Historical Resource Sites STAFF RECOMMENDATION Review the Historic Resources Inventory Update of the Centre City Core Area and staff report recommendations and: 1. Designate 28 properties under various HRB CRITERIA, as indicated on the attached spreadsheet; 2. Note and file nine properties not meeting hi storic designation criteria; and 3. Affirm new California Historical Resources Status Codes for all surveyed properties, including eligibility to the National Register of Histmic Places for five properties. -~~ -~ Planning Department ¥ of 202 CStreet, MS 4A • Sa n Di ego, CA 921 01·3865 DIVERS ITY Tel (619) 235·5200 Fax (619) 533·5951 •11"-CiS lli A.. T:lGtiH:~ BACKGROUND This item is being brought before the Historical Resources Board by the Centre City Development Corporation (CCDC) to pro-actively determine significant historic properties for planning purposes associated with the update of the Centre City Community Plan in advance of re-development. This Historic Resources Inventory Update of the Core Area incorporates the findings of two previous surveys, one conducted in 1980 by Dr. -

Timeline of San Diego History Since 1987

Timeline of San Diego History Since 1987 1987 Father Joe Carroll opens St. Vincent de Paul Village downtown, with services for the homeless. 1987 Skipper Dennis Conner, at the helm of "Stars and Stripes", wins the America's Cup for the San Diego Yacht Club, defeating Australia's "Kookaburra". He wins again in 1988. Jan 26, 1988 San Diego hosts its first Super Bowl, in San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium. Washington Redskins beat Denver Broncos 42-10. 1988 America's Cup yacht race is held in San Diego; again in 1992 and 1995. 1989 San Diego Convention Center opens. 1989 First San Diego River Improvement Project completed on reclaimed Mission Valley river banks. 2 Timeline of San Diego History Since 1987 1990 City of San Diego population reaches 1,110,549. San Diego County population is 2,498,016. Population table. 1990 California State University, San Marcos, opens. 1990 Former San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson is elected Governor of California, the state's first governor from San Diego. 1992 General Dynamics-Convair begins closing local operations. July, 1993 U.S. Navy announces Naval Training Center to be closed under terms of the Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990. 1994 California Center for the Arts, Escondido, opens. 1995 ARCO Olympic Training Center opens in Chula Vista. January 29, 1995 San Diego Chargers lose by a score of 49-26 to the San Francisco 49ers at Super Bowl XXIX in Miami. 1995 Reconstructed House of Charm opens in Balboa Park. Read history of the House of Charm. 1995 Mayor Susan Golding announces plans for the expansion of San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium. -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

The Little Green Book of Tennis

THE LITTLE GREEN BOOK OF TENNIS SECOND EDITION TOM PARHAM Copyright © 2015 by Tom Parham All rights reserved. No part of the content of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of Mr. Tom Parham 202 Blue Crab Court Emerald Isle, N. C. 28594 ISBN #: 978-0-9851585-3-8 Second Edition LOC #2015956756 Printed and Bound in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 CONTENTS Harvey Penick’s Book...............................................................................................................2 Mentors...................................................................................................................4 Jim Leighton..............................................................................................................................4 Jim Verdieck...............................................................................................................................6 Keep on Learning......................................................................................................................8 If I Die..........................................................................................................................................9 Ten Ground Stroke Fundamentals......................................................................................9 Move! Concentrate! What DoThey Mean?......................................................................12 Balance Is the Key to GoodTennis........................................................................................13 -

Sdc Pds Rcvd 01-04-17 Tm5605

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY OF THE POPLAR MEADOW TENTATIVE MAP PROJECT, JAMUL, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA PDS2015-TM-5605/ PDS2015-ER-15-19-005 Poplar Meadow Tentative Map Lead Agency: County of San Diego Department of Planning and Land Use Contact: Benjamin Mills 5510 Overland Avenue San Diego, CA 92123 (858) 694-2960 Preparer: Andrew R. Pigniolo Carol Serr Laguna Mountain Environmental, Inc. 7969 Engineer Road, Suite 208 San Diego, CA 92111 (858) 505-8164 ________________________________________ Project Proponent: Mr. Dave Back Back’s Construction, Inc. 1602 Front Street Suite #102 San Diego, CA 92101 May 2016 SDC PDS RCVD 01-04-17 TM5605 NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA BASE INFORMATION Authors: Andrew R. Pigniolo and Carol Serr Firm: Laguna Mountain Environmental, Inc. Client/Project Proponent: Mr. Dave Back Report Date: March 2016 Report Title: Cultural Resource Survey of the Poplar Meadow Tentative Map Project, Jamul, San Diego County, California PDS2015-TM-5605/ PDS2015-ER-15-19-005 Type of Study: Cultural Resource Survey New Sites: None Updated Sites: None USGS Quadrangle: Jamul Mountains Quadrangle 7.5' Acreage: 10-Acres Permit Numbers: PDS2015-TM-5605 Key Words: County of San Diego, Jamul, 2882 Poplar Meadow Lane, Negative Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................v 1.0 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1