Maureen Connolly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WTT . . . at a Glance

WTT . At a glance World TeamTennis Pro League presented by Advanta Dates: July 5-25, 2007 (regular season) Finals: July 27-29, 2007 – WTT Championship Weekend in Roseville, Calif. July 27 & 28 – Conference Championship matches July 29 – WTT Finals What: 11 co-ed teams comprised of professional tennis players and a coach. Where: Boston Lobsters................ Boston, Mass. Delaware Smash.............. Wilmington, Del. Houston Wranglers ........... Houston, Texas Kansas City Explorers....... Kansas City, Mo. Newport Beach Breakers.. Newport Beach, Calif. New York Buzz ................. Schenectady, N.Y. New York Sportimes ......... Mamaroneck, N.Y. Philadelphia Freedoms ..... Radnor, Pa. Sacramento Capitals.........Roseville, Calif. St. Louis Aces................... St. Louis, Mo. Springfield Lasers............. Springfield, Mo. Defending Champions: The Philadelphia Freedoms outlasted the Newport Beach Breakers 21-14 to win the King Trophy at the 2006 WTT Finals in Newport Beach, Calif. Format: Each team is comprised of two men, two women and a coach. Team matches consist of five events, with one set each of men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles, women's doubles and mixed doubles. The first team to reach five games wins each set. A nine-point tiebreaker is played if a set reaches four all. One point is awarded for each game won. If necessary, Overtime and a Supertiebreaker are played to determine the outright winner of the match. Live scoring: Live scoring from all WTT matches featured on WTT.com. Sponsors: Advanta is the presenting sponsor of the WTT Pro League and the official business credit card of WTT. Official sponsors of the WTT Pro League also include Bälle de Mätch, FirmGreen, Gatorade, Geico and Wilson Racquet Sports. -

2020 Topps Transcendent Tennis Checklist Hall of Fame

TRANSCENDENT ICONS 1 Rod Laver 2 Marat Safin 3 Roger Federer 4 Li Na 5 Jim Courier 6 Andre Agassi 7 David Hall 8 Kim Clijsters 9 Stan Smith 10 Jimmy Connors 11 Amélie Mauresmo 12 Martina Hingis 13 Ivan Lendl 14 Pete Sampras 15 Gustavo Kuerten 16 Stefan Edberg 17 Boris Becker 18 Roy Emerson 19 Yevgeny Kafelnikov 20 Chris Evert 21 Ion Tiriac 22 Charlie Pasarell 23 Michael Stich 24 Manuel Orantes 25 Martina Navratilova 26 Justine Henin 27 Françoise Dürr 28 Cliff Drysdale 29 Yannick Noah 30 Helena Suková 31 Pam Shriver 32 Naomi Osaka 33 Dennis Ralston 34 Michael Chang 35 Mark Woodforde 36 Rosie Casals 37 Virginia Wade 38 Björn Borg 39 Margaret Smith Court 40 Tracy Austin 41 Nancy Richey 42 Nick Bollettieri 43 John Newcombe 44 Gigi Fernández 45 Billie Jean King 46 Pat Rafter 47 Fred Stolle 48 Natasha Zvereva 49 Jan Kodeš 50 Steffi Graf TRANSCENDENT COLLECTION AUTOGRAPHS TCA-AA Andre Agassi TCA-AM Amélie Mauresmo TCA-BB Boris Becker TCA-BBO Björn Borg TCA-BJK Billie Jean King TCA-CD Cliff Drysdale TCA-CE Chris Evert TCA-CP Charlie Pasarell TCA-DH David Hall TCA-DR Dennis Ralston TCA-EG Evonne Goolagong TCA-FD Françoise Dürr TCA-FS Fred Stolle TCA-GF Gigi Fernández TCA-GK Gustavo Kuerten TCA-HS Helena Suková TCA-IL Ivan Lendl TCA-JCO Jim Courier TCA-JH Justine Henin TCA-JIC Jimmy Connors TCA-JK Jan Kodeš TCA-JNE John Newcombe TCA-KC Kim Clijsters TCA-KR Ken Rosewall TCA-LN Li Na TCA-MC Michael Chang TCA-MH Martina Hingis TCA-MN Martina Navratilova TCA-MO Manuel Orantes TCA-MS Michael Stich TCA-MSA Marat Safin TCA-MSC Margaret Smith Court TCA-MW -

The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children's Picturebooks

Strides Toward Equality: The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children’s Picturebooks Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebekah May Bruce, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Michelle Ann Abate, Advisor Patricia Enciso Ruth Lowery Alia Dietsch Copyright by Rebekah May Bruce 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines nine narrative non-fiction picturebooks about Black American female athletes. Contextualized within the history of children’s literature and American sport as inequitable institutions, this project highlights texts that provide insights into the past and present dominant cultural perceptions of Black female athletes. I begin by discussing an eighteen-month ethnographic study conducted with racially minoritized middle school girls where participants analyzed picturebooks about Black female athletes. This chapter recognizes Black girls as readers and intellectuals, as well as highlights how this project serves as an example of a white scholar conducting crossover scholarship. Throughout the remaining chapters, I rely on cultural studies, critical race theory, visual theory, Black feminist theory, and Marxist theory to provide critical textual and visual analysis of the focal picturebooks. Applying these methodologies, I analyze the authors and illustrators’ representations of gender, race, and class. Chapter Two discusses the ways in which the portrayals of track star Wilma Rudolph in Wilma Unlimited and The Quickest Kid in Clarksville demonstrate shifting cultural understandings of Black female athletes. Chapter Three argues that Nothing but Trouble and Playing to Win draw on stereotypes of Black Americans as “deviant” in order to construe tennis player Althea Gibson as a “wild child.” Chapter Four discusses the role of family support in the representations of Alice Coachman in Queen of the Track and Touch the Sky. -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

US Open Doubles Champion Leaderboard Doubles Champion Leaders Among Players/Teams from the Open Era

US Open Doubles Champion Leaderboard Doubles Champion Leaders among players/teams from the Open Era Leaderboard: Titles per player (9) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Martina Navratilova (USA) 1977 1978 1980 1983 1984 1986 1987 1989 1990 (6) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Mike Bryan (USA) 2005 2008 2010 2012 2014 2018 | * Tied for most all-time among men Darlene Hard (USA) 1969 (1958 1959 1960 1961 1962) * Richard Sears (USA) 1882 1883 1884 1885 1886 1887 * Holcombe Ward (USA) 1899 1900 1901 1904 1905 1906 (5) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Bob Bryan (USA) 2005 2008 2010 2012 2014 Margaret Court (AUS) 1968 1970 1973 1975 (1963) Gigi Fernández (USA) 1988 1990 1992 1995 1996) Billie Jean King (USA) 1974 1978 1980 (1964 1967) Pam Shriver (USA) 1983 1984 1986 1987 1991 (4) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Maria Bueno (BRA) 1968 (1960 1962 1966) Rosemary Casals (USA) 1971 1974 1982 (1967) Robert Lutz (USA) 1968 1974 1978 1980 John McEnroe (USA) 1979 1981 1983 1989 Stan Smith (USA) 1968 1974 1978 1980 Natalia Zvereva (BLR) 1991 1992 1995 1996 (3) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Peter Fleming (USA) 1979 1981 1983 Martina Hingis (SUI) 1998 2015 2017 John Newcombe (AUS) 1971 1973 (1967) Jana Novotná (CZE) 1994 1997 1998 Leander Paes (IND) 2006 2009 2013 Virginia Ruano Pascual (ESP) 2002 2003 2004 Lisa Raymond (USA) 2001 2005 2011 Fred Stolle (AUS) 1969 (1965 1966) Paola Suárez (ARG) 2002 2003 2004 Betty Stöve (NED) 1972 1977 1979 Todd Woodbridge (AUS) 1995 1996 2003 Mark Woodforde (AUS) 1989 1995 1996 (2) US OPEN DOUBLES TITLES Judy Tegart Dalton (AUS) 1970 1971 Nathalie Dechy (FRA) 2006 -

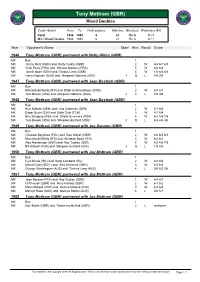

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles Code->Event From To Participations Matches Won/Lost Walkovers W/L Total 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 MX->Mixed Doubles 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 Year Opponent's Name Seed Rnd Result Score 1946 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Betty Hilton (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Jimmy Hunt (GBR) and Betty Coutts (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/1 6/3 MX Yvon Petra (FRA) and Simone Mathieu (FRA) 3 W 6/4 6/3 MX Jannik Ipsen (DEN) and Gladys Lines (GBR) 4 W 1/6 6/3 6/4 MX Harry Hopman (AUS) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 1 Q L 4/6 2/6 1947 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Bibbi Gullbrandsson (SWE) 2 W 6/3 6/1 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 2 3 L 0/6 3/6 1948 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Kurt Nielsen (DEN) and Lisa Andersen (DEN) 2 W 6/1 6/3 MX Edgar Buchi (SUI) and Edith Sutz (TCH) 3 W 6/1 6/4 MX Eric Sturgess (RSA) and Sheila Summers (RSA) 4 W 6/2 1/6 7/5 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 6/4 4/6 3/6 1949 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Gannon (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Czeslaw Spychala (POL) and Bea Walter (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/3 6/3 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Annelise Bossi (ITA) 3 W 6/2 6/2 MX Alex Hamburger (GBR) and Kay Tuckey (GBR) 4 W 6/2 4/6 7/5 MX Bill Sidwell (AUS) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 1/6 4/6 1950 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Mottram (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Cyril Kemp (IRL) and Betty Lombard (IRL) 2 W 6/2 6/4 MX Marcel Coen (EGY) and Alex McKelvie (GBR) 3 W 6/3 6/4 MX George Worthington (AUS) and -

Meet the Summer Camp Staff 2015 "Experience Is the Best Teacher!"

Meet The Summer Camp Staff 2015 "Experience is the best teacher!" Gary Engelbrecht Chris Ayer SOME FUN FACTS ABOUT Camp Director Basketball/Swim • SOME OF OUR • Head Pro and NBA D-League Profes- Director of Tennis sional for the world NEWEST COACHES. at TRFC for 34 champion Miami Heat Tennis Pro Lamine Bangoura at- years • McDonalds High school tended the world famous Bollettieri • Gary worked with All-American at Amphi Tennis Academy and was roommates • more than 30 Played College Division with Pete Sampras! He was also the #1 nationally ranked I Basketball for Loyola Junior Tennis player Marymount University players, 20 Southwest Champions, and more In Africa. Tennis than 50 AZ State High School Champs. • Played on the Loyola water polo team coaches Tatum • Worked for “Hall of Fame” coaches Nick Bollet- Rochin and Alan tieri and Harry Hopman. Brian Ramirez Barrios played Di- • University of Arizona Women’s Tennis Assis- Tennis Pro • vision I tennis for tant (6 years) including “Final Four” appear- U of A Women's Tennis Assistant Coach. ance and PAC 10 Championship. • Stanford Women's Tennis Assistant Coach. Northern Arizona • Tennis Coach Tatum Nike Tennis Camp Assistant Director in Stan- University. All Rochin played D1 tennis in college! Sam Ciulla ford. sports coach Kailey Camp Director • Brian has been with the Tucson Racquet Club Mellen has a soft- • Associate Head Tennis Pro at Tuc- for 6 years. ball scholarship at Coastal Carolina • son Racquet Club for 34 years. Brian is the proud parent of his 11 month old University. Soccer star Raymond son Parker. -

Congreso Nacional

“2019–Año de la Exportación” CONGRESO NACIONAL CÁMARA DE SENADORES SESIONES ORDINARIAS DE 2019 ORDEN DEL DÍA Nº 356 Impreso el día 18 de julio de 2019 SUMARIO COMISIÓN DE DEPORTE Dictamen en el proyecto de declaración del señor senador Reutemann, expresando beneplácito a la deportista Gabriela Sabatini, quien fue honrada con el premio Philippe Chatrier, por la Federación Internacional de Tenis. (S.-1722/19) DICTAMEN DE COMISIÓN Honorable Senado: Vuestra Comisión de Deporte ha considerado el proyecto de declaración del señor senador Carlos Alberto Reutemann, registrado bajo expediente S-1722/19, solicitando que exprese “beneplácito a la deportista argentina Gabriela Sabatini, quien fue honrada con el premio Philippe Chatrier, por la Federación Internacional de Tenis”; y por las razones que dará el miembro informante, aconseja su aprobación. De acuerdo a lo establecido por el artículo 110 del Reglamento del Honorable Senado, este dictamen pasa directamente al orden del día. Sala de la comisión, 17 de julio de 2019. Julio C. Catalán Magni – Néstor P. Braillard Poccard – Ana M. Ianni – Marta Varela – Gerardo A. Montenegro – Mario R. Fiad – Silvia del Rosario Giacoppo – Pamela F. Verasay – José R. Uñac. PROYECTO DE DECLARACION El Senado de la Nación DECLARA Su beneplácito por el reconocimiento a la deportista argentina Gabriela (Gaby) Sabatini, quien fue honrada con el Premio Philippe Chatrier que anualmente confiere la Federación Internacional de Tenis. Carlos A. Reutemann “2019–Año de la Exportación” FUNDAMENTOS Señora Presidente: Gabriela Sabatini, la máxima tenista argentina de la historia, recibió en París, en el marco de uno de sus torneos predilectos, el de Roland Garros, donde fue en 1984 campeona junior con apenas 14 años de edad, el máximo honor que confiere la Federación Internacional de Tenis (ITF), el Premio Philippe Chatrier. -

In 4-Ball Golf |Louise Brough

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C.'** A-11 Adios Boy Sets Saturday. July m, hm to Win Redskins to Test Punters Record In Today's Scrimmage Bj LEWIS F. ATCHISON !he1 thought Charlie Justice did • 'Triple Star Btaff Correspondent ( Crown' right especially all last season, BALTIMORE. July 23 (Spe- LOS ANGELES. July 23.—The j’when he ran several times from jj cial).—A new track record is in Redskins will test their back-I punt formation—once against Baltimore Raceway’s books to- field—just for kicks—this after- < the Browns. day, put night by noon in the scrimmage be- 1 “Janowicz was rusty after here last Adios final playing Boy in winning Maryland fore next week’s intra-squad baseball,'’ Joe pointed the may ¦' !&- _jf i “triple crown” pacing trophy. game in the Pasadena Rose 1 out. “and it still take him 4-year-old bay flj words, punting a little time to get re-adjusted The stallion Bowl. In other 1 by 1 high agenda, to football, but can owned J. S. Turner of Nas- was on the al- 1 he do it. mtr uy sawadox, Va., by though Coach Joe Kuharich and We know he can. We know and driven HP tr ability. HflPyY. Howard Camden, won the final his aides planned a review of : Leßaron’s That one SIO,OOO leg of the triple crown in the entire offensive setup. year in the Canadian League . ¦Hag— 2:00%- a new lifetime record on i Eddie Leßaron, who did most; 1 didn’t hurt Eddie at all. -

United States Vs. Czech Republic

United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREVIEW NOTES PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES (U.S. AND CZECH REPUBLIC) U.S. FED CUP TEAM RECORDS U.S. FED CUP INDIVIDUAL RECORDS ALL-TIME U.S. FED CUP TIES RELEASES/TRANSCRIPTS 2017 World Group (8 nations) First Round Semifinals Final February 11-12 April 22-23 November 11-12 Czech Republic at Ostrava, Czech Republic Czech Republic, 3-2 Spain at Tampa Bay, Florida USA at Maui, Hawaii USA, 4-0 Germany Champion Nation Belarus at Minsk, Belarus Belarus, 4-1 Netherlands at Minsk, Belarus Switzerland at Geneva, Switzerland Switzerland, 4-1 France United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 For more information, contact: Amanda Korba, (914) 325-3751, [email protected] PREVIEW NOTES The United States will face the Czech Republic in the 2017 Fed Cup by BNP Paribas World Group Semifinal. The best-of-five match series will take place on an outdoor clay court at Saddlebrook Resort in Tampa Bay. The United States is competing in its first Fed Cup Semifinal since 2010. Captain Rinaldi named 2017 Australian Open semifinalist and world No. 24 CoCo Vandeweghe, No. 36 Lauren Davis, No. 49 Shelby Rogers, and world No. 1 doubles player and 2017 Australian Open women’s doubles champion Bethanie Mattek-Sands to the U.S. team. Vandeweghe, Rogers, and Mattek- Sands were all part of the team that swept Germany, 4-0, earlier this year in Maui. -

That Changed Everything

2 0 2 0 - A Y E A R that changed everything DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION DECEMBER 18, 2020 For Florida students in grades 6 - 8 PRESENTED BY THE FLORIDA COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN To commemorate and honor women's history and PURPOSE members of the Florida Women's Hall of Fame Sponsored by the Florida Commission on the Status of Women, the Florida Women’s History essay contest is open to both boys and girls and serves to celebrate women's history and to increase awareness of the contributions made by Florida women, past and present. Celebrating women's history presents the opportunity to honor and recount stories of our ancestors' talents, sacrifices, and commitments and inspires today's generations. Learning about our past allows us to build our future. THEME 2021 “Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action.” ― Marjory Stoneman Douglas This year has been like no other. Historic events such as COVID-19, natural disasters, political discourse, and pressing social issues such as racial and gender inequality, will make 2020 memorable to all who experienced it. Write a letter to any member of the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame, telling them about life in 2020 and how they have inspired you to work to make things better. Since 1982, the Hall of Fame has honored Florida women who, through their lives and work, have made lasting contributions to the improvement of life for residents across the state. Some of the most notable inductees include singer Gloria Estefan, Bethune-Cookman University founder Mary McLeod Bethune, world renowned tennis athletes Chris Evert and Althea Gibson, environmental activist and writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Pilot Betty Skelton Frankman, journalist Helen Aguirre Ferre´, and Congresswomen Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Carrie Meek, Tillie Fowler and Ruth Bryan Owen. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d.