The Viability of Local Designation in the Peoplestown Neighborhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

2. Hotel Information 3. Room Information 4. Deposit

The Atlanta International DEADLINE: Tuesday, November 15, 2016 Gift & Home Furnishings Market® Only one room request per form please. Make additional copies if necessary. SHOWROOMS To make a reservation, please fax form to Tara Yorke at January 10 – 17, 2017 678.686.5287 or email [email protected]. TEMPORARIES Note: Retailers are only eligible to participate in one promotion. January 12 – 16, 2017 Confirmations will be sent via email from [email protected]. Hotel availability is based on a first come, first served basis and therefore not guaranteed. ( ) 1. CONTACT INFORMATION REQUIRED STORE/COMPANY NAME CUSTOMER NAME STREET ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP POSTAL CODE EMAIL PHONE LAST SHOW ATTENDED AT AMERICASMART (if applicable) STORE TYPE 2. HOTEL INFORMATION Rank three hotel choices from the list provided. ARRIVAL DATE 1. 2. DEPARTURE DATE 3. 3. ROOM INFORMATION Please supply names of all persons to occupy room and Room Type: type of room. Single Dbl (2ppl/1bed) Dbl/DBL (2ppl/2beds) King-size bed SPECIAL REQUESTS I am in need of an ADA accessible room. I may need special assistance from the hotel in the event of an emergency. Note: room type & special requests based on availability at check-in. Other, please list: 4. DEPOSIT INFORMATION: Reservations will NOT be processed without a credit card guarantee. The hotel reserves the right to charge a deposit of one night’s room and tax. (GA 16% tax). Please read through all cancellation policies in your confirmation email. CREDIT CARD NUMBER TYPE EXPIRATION DATE (after July 2016) ✗ NAME (printed) SIGNATURE FOR AMC Confirmation Number: USE ONLY #NSAMC: 1 NT BG PPP TY OFFICIAL HOTELS & RATES The Atlanta International Gift & Home Furnishings Market Permanent Showrooms: Tuesday, January 12 – Tuesday, January 19, 2017 Temporaries: Thursday, January 14 – Monday, January 18, 2017 The Atlanta International Area Rug Market Permanent: Wednesday, January 13 – Saturday, January 16, 2017 Temporaries: Wednesday, January 13 – Saturday, January 16, 2017 AmericasMart, Bldg. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

A Vibrant Retail Opportunity in the Heart of Downtown Atlanta

A VIBRANT RETAIL OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF DOWNTOWN ATLANTA PEACHTREECENTER.COM AN ICON REBORN IT’S BEEN AN ICONIC DOWNTOWN DESTINATION DISTRICT FOR NEARLY 50 YEARS. 6 2.3 50 3 OFFICE MILLION RESTAURANTS ON-SITE BUILDINGS SQUARE FEET & RETAIL HOTELS 2 DOWNTOWN A $14 Billion economic impact from tourism activity ATLANTA in Downtown Atlanta in 2014. 2015 MARKET HIGHLIGHTS 5.2 MILLION 14,491 TOURISTS SURROUNDING HOTEL ROOMS 2.1 MILLION 139,000+ CONVENTIONEERS DAYTIME EMPLOYEES 20.4 MILLION 15,000 32,000 ATTENDEES AT ATTRACTIONS, RESIDENTS STUDENTS SPORTING EVENTS AND CONCERTS 3 DOWNTOWN ATLANTA ALL IN THE MIX 223 CASUAL DINING ESTABLISHMENTS Ranked among Atlanta Business Chronicle’s Top 25 Restaurants in 39 Sales: Hard Rock PLACES FOR COFFEE & DESSERTS Cafe, Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse and Sundial Restaurant, Bar & View. 62 ENTERTAINMENT VENUES Named to Yelp’s Top 100 Places to Eat in 2016: Aviva by Kameel and Gus’s World Famous 43 Fried Chicken FULL-SERVICE RESTAURANTS 4 LEGEND 6 OFFICE RESIDENTIAL RETAIL, OFFICE 1 1 SUNTRUST THE OFFICE (Apartments) & MULTIFAMILY 2 10 2 438 APARTMENT UNITS 191 TOWER UNDER CONSTRUCTION POST CENTENNIAL 4 3 PARK 100 PEACHTREE 3 2 4 FULTON SUPPLY 1 LOFTS ALLEN PLAZA 4 1 5 AMERICASMART 200 EDGEWOOD GEORGIA WORLD ATLANTA FEDERAL CONGRESS CENTER PEACHTREE CENTER CENTER 2.3M SF OFFICE SPACE 5 M CENTENNIAL 6 CITY PLAZA OLYMPIC PARK CENTENNIAL 6 TOWER 2 CENTENNIAL 7 PLAZA GEORGIA PACIFIC 7 TOWER PHILIPS 7 6 STONEWALL LOFTS ARENA 8 3 8 FLATIRON MERCEDES-BENZ BUILDING INTOWN LOFTS 8 12 STADIUM 9 4 LEGACY LOFTS M 10 THE POINT AT 5 GEORGIA STATE WESTSIDE UNIVERSITY 11 VILLAGES AT 3 CASTLEBERRY 12 8 CITY WALK 9 7 11 5 5 PEACHTREE Over 10 million CENTER foot falls annually. -

Neighborhood Profile: Lakewood Heights

Neighborhood Profile: Lakewood Heights Investment Area Typology: Vulnerable Total Single Family Parcels Total Multi-Family Parcels Total Commercial/Industrial/Public Parcels Vacant Lots Unsurveyable Parcels Total Parcels 685 1 173 132 144 1135 Legend Structure Condition Green Space 210 Good # of Structu r e s : 327 Vacant Structures # of Structures: # of Vacant L o t s : 132 Fair # of Structur e s : 221 No Structure Poor # of Structur e s : 114 Not Visible # of Structure s : 3 Inset Map Deteriorated # of Structure s : 21 No Data Available # of Structure s : 144 M IL T O T R S ENGLEWOOD A N E VE A K V T j[ E C Adair Park Peoplestown N I O R Pittsburgh M T W CLIMAX ST Boulevard Heights T D L C I D D S A N O M L LINCOLN ST H O N L I O C N AVE R U I L H Englewood Manor ERIN AVE R A E G A A H K D B M NOLAN ST D R K E ORD L R MANF M V IL A W NFO N RD RD D T A A DILL AVE O O T V H S O N E E S H L V E Phoenix II Park D A L G BURRO U U A V V A I B E R O S j[ V A CUS B TER AVE L S N Capitol View Manor E A T E BISBEE AVE S H H T Benteen Park F A LYNNHAVEN DR I E E M [V L j High Point T O D Chosewood Park A S U S N DECKNER AVE R N T E j[ Y South Atlanta O Capitol View E NGF j[ T A ORD JR PL A L T V Kimpson Park S N R E E BROWN AV N Emma Millican Park E U U T B F H S D ST NNE N T A L R L R A R ST O K O N ET A R T C T GA The Villages at Carver R R S MA C N S I PARK AVE I A E N L D T P N W G j[ R S T N A M S E S R P LDON AVE O Joyland H U T O C K S O T Y CLAIRE TAFT ST C S DR N R I A R E T H P W W WEN AVE ET O HIPP ST D BO L T R N A S A W H W O TURMAN AVE T E D L Amal Heights L R T I P S L C Y RHODESIA AVE E E R L T T V A O A S H L Y D W L L R R U E IC Sylvan Hills ADAIR AVE O T P H Betmar LaVilla G W M A S O T E N ASHWOOD AVE V D S CLAIRE DR A Sou A th E D T V R Y N S A V E i I E v E B N e R L V r D W r HILLSIDE AV A E O E R e D O IR I iv O H Thomasville Heights A R C FAIR DR F A R O S K F h W E K t E T S C u K B GRANT ST o I C o A D u P I S L O R A ST t D O EN h P W O HEL R R LA E W K iv Lakewood Heights e R r N F O S R R Y S South Bend Park E M o D R u E I P John C. -

Downtown Atlanta

the green line downtown atlanta Central Atlanta Progress Atlanta Downtown Improvement District 1 the green line / downtown atlanta CENTENNIAL GWCC - C OLYMPIC PARK GWCC - B CONTEXT GWCC - A CNN CENTER GEORGIA DOME INTERNATIONAL PLAZA PHILIPS ARENA DOME/CNN/GWCC MARTA STATION STUDY AREA (Approx. 94 Ac) FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION RUSSELL FEDERAL BLDG GSU MARTA STATION STATE ATLANTA COCAPITOL CITY HALL 2 the green line / downtown atlanta GOALS DOME/CNN/GWCC MARTA STATION FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION GA STATE MARTA STATION GOALS Create an implementable plan that ~ Envisions an iconic destination ~ Stitches the city together through public space, transit and daily life ~ Fosters public and private investment 3 the green line / downtown atlanta CNN CENTER 1. Multimodal passenger terminal built INTERNATIONAL with terminal entrance at viaduct level PHILIPS ARENA PLAZA and transit connections below 2. Railroad Gulch – subdivided by new streets at viaduct level– creating DOME/CNN/GWCC AJC MARTA STATION development sites 3 STATE BAR BUILDING 4 3. New retail, entertainment, hotel uses 2 expand activity of GWCC / GA Dome / 6 Philips Arena 4. New office space takes advantage of HUD 1 enhanced regional transit connection 5. New and improved access to MARTA rail stations 5 6. New triangular park space can be FIVE POINTS MARTA STATION closed to vehicular traffic to host special events and festivals RUSSELL FEDERAL BLDG KEY MAP Typical retail storefronts at viaduct level Atlantic Station – example of new streets to create future development sites 4 the green line / downtown atlanta 1. Transformed Five Points station structure with new platform access and programmed plaza 2. -

Subarea 1 Atlanta Beltline Master Plan

Atlanta BeltLine Master Plan SUBAREA 1 PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS REPORT Prepared for Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. by Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates with Grice & Associates, Inc. and Smith Dalia Architects Adopted by the Atlanta City Council on December 6, 2010 this page left intentionally blank this report has been formatted to be printed double-sided in an effort to save paper ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed The Honorable Kasim Reed, City of Atlanta Mayor The Honorable Joyce M. Shepherd, Atlanta City Council ATLANTA CITY COUNCIL District 12 Ceasar Mitchell, President John Somerhalder, AGL Resources, Chair of the Board, BeltLine Partnership Carla Smith, District 1 Subarea 1 Planning Committee Kwanza Hall, District 2 Michael Altermann, West End Mall Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Patrick Berry, Westview Cleta Winslow, District 4 Bakari Brooks, Atlanta Housing Authority Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Allean Brown, NPU S Liaison Alex Wan, District 6 Danielle Carney, NPU T Liaison Howard Shook, District 7 Ed Chang, KIPP Strive Yolanda Adrean, District 8 Jo Ann Chitty, Selig Enterprises Felicia A. Moore, District 9 Teeya Davis, Cleta Winslow’s Office C. T. Martin, District 10 Reverend Elligan Keisha Bottoms, District 11 Douglas Fitzgerald, Donnelly Gardens Apartments Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Vonda Henry, West End Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 at Large Deudishar Jenkins, Mimms Enterprises Aaron Watson, Post 2 at Large Herb Joseph, Atlanta Public Schools H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 at Large Nia Knowles, NPU T ATLANTA BELTLINE, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Travie Leslie, NPU V Elizabeth B. Chandler, Chair Felicia Phillips, Oakland City Clara Axam, Vice Chair, Enterprise Community Partners, Inc.; Derek Roqumore, Outdoor Activity Center MARTA Board of Directors David Sitt (out of town participant), Kroger Citi Center Joseph A. -

Trust Company Bank Building Landmark Building / Site (LBS)

ATTACHMENT “A” TO NOMINATION RESOLUTION C I T Y O F A T L A N T A KASIM REED DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT TIM KEANE MAYOR 55 TRINITY AVENUE, S.W. SUITE 3350 – ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30303-0308 Commissioner 404-330-6145 – FAX: 404-658-7491 www.atlantaga.gov CHARLETTA WILSON JACKS Director, Office of Planning Designation Report for Trust Company Bank Building Landmark Building / Site (LBS) Application Number: N-16-382 / D-16-382 Proposed Category of Designation: Landmark Building / Site (LBS) Zoning Categories at Time of Designation: I-1 and Beltline Zoning Overlay District: 17 Land Lot(s): 57 Fulton County, City of Atlanta Designation Report Sections: 1. Eligibility Criteria 2. Findings 3. Physical Description of the Property 4. Period of Significance 5. Narrative Statement of Significance 6. Biography, History, and Architectural Context 7. Contributing / Non-Contributing Structures 8. Bibliography 9. Potential for Transfer of Development Rights and Economic Incentives 10. General Boundary Description 11. Boundary Justification 12. General Plat Map Designation Report for the Trust Company Bank Building LBS – N-16-382 / D-16-382 Page 1 of 29 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA As more fully described in this Designation Report, the Trust Company Bank Building Landmark Building / Site (LBS) meets the following criteria for a Landmark District, as defined in Section 16- 20.004(b)(2)(a): Group I - Historic Significance: (Three (3) total criteria - if qualifying under this group alone, at least one (1) criterion must be met) The Trust Company Bank Building Landmark Building / Site (LBS) meets two (2) criteria: (1) The Trust Company Bank Building Landmark Building / Site (LBS) is closely associated with the life and work of a person of exceptionally high significance to the City of Atlanta (the “City). -

Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20

Altanta - Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Generation Atlanta 336 60 145 62 6 Elan Madison Yards 495 142 153 58 9 Skylark 319 14 70 10 Ashley Scholars Landing 135 59 14 NOVEL O4W 233 148 154 110 17 Adair Court 91 65 Total Lease Up 1,609 1 144 21 Ascent Peachtree 345 26 Castleberry Park 130 27 Link Grant Park 246 21 35 Modera Reynoldstown 320 111 University Commons 239 127 39 915 Glenwood 201 Total Planned 6,939 64 68 Total Under Construction 1,242 111 126 66 100 26 109 205 116 Abbington Englewood 80 155 50 Milton Avenue 320 129 99 120 Hill Street 280 124 103 53 Broadstone Summerhill 276 124 222 Mitchell Street 205 67 101 54 Georgia Avenue 156 134 Mixed-Use Development 100 125 240 Grant Street 297 10 125 58 Centennial Olympic Park Drive 336 126 41 Marietta St 131 59 Courtland Street Apartment Tower 280 127 Luckie Street 100 35 137 104 60 Spring Street 320 128 Modera Beltline 400 6 62 Ponce De Leon Avenue 129 Norfolk Southern Complex Redevelopment 246 Mixed-Use Development 135 130 72 Milton Apartments - Peoplestown 383 64 220 John Wesley Dobbs Avenue NE 321 53 27 65 Angier Avenue 240 131 Hank Aaron Drive 95 66 Auburn 94 132 Summerhill 965 39 67 McAuley Park Mixed-Use 280 133 Summerhill Phase II 521 98 54 132 68 StudioPlex Hotel 56 134 930 Mauldin Street 143 133 70 North Highland 71 137 Memorial Drive Residential Development 205 142 Quarry Yards 850 96 Chosewood Park 250 105 17 98 565 Hank Aaron Drive 306 144 Atlanta First United Methodist 100 99 Avery, The 130 145 Echo Street 650 100 Downtown -

Housing & Mixed-Use

HOUSING & MIXED-USE TABLE OF CONTENTS Housing & Mixed-Use Practice Area 01 Multifamily & Mixed-Use 02 Adaptive Re-Use 03 Student Housing 04 Urban Design & Planning 05 Firm Profile 06 01 HOUSING & MIXED-USE PRACTICE AREA Lord Aeck Sargent’s Housing & Mixed-Use practice area provides creative solutions for new and innovative mixed-use communities. Our focus is on urban-infill projects of varying sizes that have a direct impact on the urban environment. We have been involved in projects at the master planning and urban design levels, including assistance with planning for neighborhood development, projects that encompass multi-acre sites, single-family residential neighborhood planning in undeveloped urban core areas and large mixed-use developments. Our services include extensive planning and zoning work, from initial site analysis through the neighborhood and jurisdictional review process. Our projects are complex and often involve a mix of new construction, adaptive reuse, historic preservation and mixed-use programs. “Lord Aeck Sargent Architecture did 02 a fantastic job executing the design for a difficult site and complex project. They provided a highly qualified team that designed a remarkable project and addressed all issues during construction.” William N. Bollwerk Alliance Residential Company MULTIFAMILY & MIXED-USE Our experience includes market-rate housing for rent and for sale, as well as affordable housing, public housing, senior housing and student housing. Our areas of expertise are in the design and planning of multifamily buildings and vertically integrated mixed-use residential developments targeted to a variety of demographic groups. We are experienced in the technical aspects of residential and mixed-use construction—from low-rise to high-rise N. -

Executive Summary 3

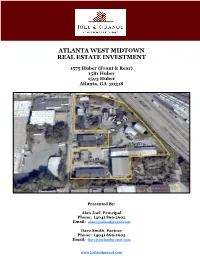

ATLANTA WEST MIDTOWN REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT 1575 Huber (Front & Rear) 1581 Huber 1593 Huber Atlanta, GA 30318 Presented By: Alan Joel, Principal Phone: (404) 869-2602 Email: [email protected] Dave Smith, Partner Phone: (404) 869-2605 Email: [email protected] www.joelandgranot.com 1575 Huber (Front & Rear) 1581 Huber 1593 Huber Table of Contents Atlanta, GA 30318 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Property Information 4 Environmental Summary 5 Aerial 7 Site Plan 8 Property Photos 9 Market / Area Information 10 Confidentiality Agreement 11 Alan Joel, Principal Dave Smith, Partner Phone: (404) 869-2602 Phone: (404) 869-2602 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The information contained herein is from other sources believed to be reliable. No independent investigation of the property or the information contained herein has been made, and no representation is made as to the accuracy or completeness thereof. Properties are subject to prior sale, withdrawal and other sales or rental conditions. Terms are subject to errors, omissions and change without notice. 1575 Huber (Front and Rear) Huber: 0.9504 Acres and 0.4304 Acres. 1.3808 Acres. 1581 Huber: 2.19 Acres. 1593 Huber: Approximately 4.14 Acres Executive Summary Total Site Size +- 7.71 Acres THE PROPERTY JGRE is pleased to offer this single tenant, net leased property investment in Atlanta, GA. The property contains 7.71 acres with 73,000 sq ft of buildings and is located in the hot Midtown West Atlanta sub- market, approximately 5 miles northwest of downtown Atlanta. The subject property is located on the east side of Huber Street near the new Top Golf development on the corner of Chattahoochee and Ells- worth Industrial. -

Haven at South Atlanta

A MARKET CONDITIONS AND PROJECT EVALUATION SUMMARY OF: HAVEN AT SOUTH ATLANTA A MARKET CONDITIONS AND PROJECT EVALUATION SUMMARY OF: HAVEN AT SOUTH ATLANTA 57 Hardwick Street SE Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia 30315 Effective Date: April 17, 2019 Report Date: April 19, 2019 Prepared for: Amon Martin Senior Developer Pennrose, LLC 675 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE, Suite 8500 Atlanta, Georgia 30308 Prepared by: Novogradac & Company LLP 4416 East-West Highway, Suite 200 Bethesda, MD 20814 240-235-1701 April 19, 2019 Amon Martin Senior Developer Pennrose, LLC 675 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE, Suite 8500 Atlanta, Georgia 30308 Re: Application Market Study for Haven at South Atlanta, located in Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia Dear Mr. Martin: At your request, Novogradac & Company LLP performed a study of the multifamily rental market in the Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia area relative to the above-referenced Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) project. The purpose of this market study is to assess the viability of the proposed 84-unit family mixed-income project. It will be a newly constructed affordable LIHTC project, with 84 revenue generating units, restricted to households earning and 60 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) or less as well as market rate. The following report provides support for the findings of the study and outlines the sources of information and the methodologies used to arrive at these conclusions. The scope of this report meets the requirements of Georgia Department of Community Affairs (DCA), including the following: • Inspecting the site of the proposed Subject and the general location. • Analyzing appropriateness of the proposed unit mix, rent levels, available amenities and site.