Missing Linkages: Restoring Connectivity to the California Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

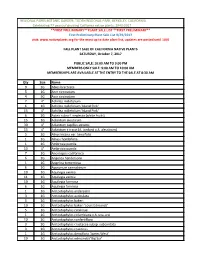

Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies Bracteata 10 1G Abutilon Palmeri 1 1G Acaena Pinnatifida Var

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 76 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2016 **FINAL**PLANT SALE LIST **FINAL** (9/30/2016 @ 6:00 PM) visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2016 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies bracteata 10 1G Abutilon palmeri 1 1G Acaena pinnatifida var. californica 18 1G Achillea millefolium 10 4" Achillea millefolium - Black Butte 28 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 8 4" Achillea millefolium 'Rosy Red' - donated by Annie's Annuals 2 4" Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' 7 4" Acmispon (Lotus) argophyllus var. argenteus 9 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 25 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Aesculus californica 1 2G Agave shawii var. shawii 2 1G Agoseris grandiflora 8 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 2 2G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 5 4" Ambrosia pumila 5 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia 9 1G Anemopsis californica 5 1G Angelica hendersonii 3 1G Angelica tomentosa 1 1G Apocynum androsaemifolium x Apocynum cannabinum 7 1G Apocynum cannabinum 5 1G Aquilegia formosa 2 4" Aquilegia formosa 4 4" Arbutus menziesii 2 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 3 1G Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffith' 11 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Big Sur Capital Preventive Maintenance (CAPM) Project Approximately a 35-Mile Section on State Route 1, from Big Sur to Carmel-By-The-Sea, in the County of Monterey

Big Sur Capital Preventive Maintenance (CAPM) Project Approximately a 35-mile section on State Route 1, from Big Sur to Carmel-by-the-Sea, in the County of Monterey 05-MON-01-PM 39.8/74.6 Project ID: 05-1400-0046 Project EA: 05-1F680 SCH#: 2018011042 Initial Study with Mitigated Negative Declaration Prepared by the State of California Department of Transportation April 2018 General Information About This Document The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), has prepared this Initial Study with Mitigated Negative Declaration, which examines the potential environmental impacts of the Big Sur CAPM project on approximately a 35-mile section of State Route 1, located in Monterey County California. The Draft Initial Study was circulated for public review and comment from January 26, 2018 to February 26, 2018. A Notice of Intent to Adopt a Mitigated Negative Declaration, and Opportunity for Public Hearing was published in the Monterey County Herald on Friday January 26, 2018. The Notice of Intent and Opportunity for Public Hearing was mailed to a list of stakeholders that included both government agencies and private citizen groups who occupy and have interest in the project area. No comments were received during the public circulation period. The project has completed the environmental compliance with circulation of this document. When funding is approved, Caltrans can design and build all or part of the project. Throughout this document, a vertical line in the margin indicates a change that has been made since the draft document -

Details of Important Plants in Rpbg

DETAILS OF IMPORTANT PLANTS IN RPBG ABIES BRACTEATA. SANTA LUCIA OR BRISTLECONE FIR. PINACEAE, THE PINE FAMILY. A slender tree (especially in the wild) with skirts of branches and long glossy green spine-tipped needles with white stomatal bands underneath. Unusual for its sharp needles and pointed buds. Pollen cones borne under the branches between needles; seed cones short with long bristly bracts extending beyond scales and loaded with pitch, the cones at the top of the tree and shattering when ripe. One of the world’s rarest and most unique firs, restricted to steep limestone slopes in the higher elevations of the Santa Lucia Mountains. Easiest access is from Cone Peak Road at the top of the first ridge back of the ocean and reached from Nacimiento Ferguson Road. Signature tree at the Garden, and much fuller and attractive than in its native habitat. ACER CIRCINATUM. VINE MAPLE. SAPINDACEAE, THE SOAPBERRY FAMILY. Not a vine but a small deciduous tree found on the edge of conifer forests in northwestern California and the extreme northern Sierra (not a Bay Area species). Slow growing to perhaps 20 feet high with pairs of palmately lobed leaves that turn scarlet in fall, the lobes arranged like an expanded fan. Tiny maroon flowers in early spring followed by pairs of winged samaras that start pink and turn brown in late summer, the fruits carried on strong winds. A beautiful species very similar to the Japanese maple (A. palmatum) needing summer water and part-day shade, best in coastal gardens. A beautiful sight along the northern Redwood Highway in fall. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Garrapata State Park Initial Study Mitigated Negative Declaration Draft

COASTAL HABITAT RESTORATION AND COASTAL TRAIL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Garrapata State Park Initial Study Mitigated Negative Declaration Draft State of California Department of Parks and Recreation Monterey District June 13, 2012 This page intentionally blank. COASTAL HABITAT RESTORATION AND COASTAL TRAIL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT IS/MND – DRAFT JUNE 2012 GARRAPATA STATE PARK CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................ 1 CHAPTER II ENVIRONMENTAL CHECKLIST...................................................... 13 I. AESTHETICS. ................................................................................ 17 II. AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY RESOURCES ...……………… 21 III. AIR QUALITY.................................................................................. 23 IV. BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 26 V. CULTURAL RESOURCES ............................................................. 48 VI. GEOLOGY AND SOILS .................................................................. 64 VII. GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS ................................................. 69 VIII. HAZARDS AND HAZARDOUS MATERIALS ................................. 70 IX. HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY .......................................... 73 X. LAND USE AND PLANNING .......................................................... 78 XI. MINERAL -

Endangered C����� N���� - S���� L���� ���, ����������� �

8/23/2018 ESCTP:: Abies bracteata Fact Sheet A Endangered C N - S L , F - P (P F) S S - F S - Habitat and Associates Discontinuous stands of one to hundreds of trees, generally comprising < 5 ha, in less fireprone areas such as steep, w-, n-, or e-facing slopes in canyons or ravines, often in moist microsites near the bottom or at the head of drainages, often in talus or scree; above 1400 m on all exposures on rocky ridgetops, bluffs, or cliffs; and occasionally on stream benches or terraces. Generally in rocky, clayey, or loamy soil, occasionally on sandstone and serpentine (Talley 1974, CNDDB 2017, CNPS 2016 & 2017). Closed-canopy stands with the shrub layer open to intermittent and a sparse herb layer occur most often within montane or lower montane hardwood– conifer forest; frequently associated with Quercus chrysolepis, Pinus coulteri, or Pinus lambertiana (Junipero Serra Peak and Cone Peak). Occasionally in chaparral (especially young trees) or riparian woodland, and, rarely, at lower elevations just upslope from redwood forest (Talley 1974). Other associates include Alnus rhombifolia, Acer macrophyllum, Arbutus menziesii, Calocedrus Santa Lucia fir (Abies bracteata), from Cyclopedia of American Horticulture, 1909. decurrens, Notholithocarpus densiflorus var. densiflorus, Pinus ponderosa var. pacifica, Quercus agrifolia var. agrifolia, Quercus parvula var. shrevei, and Umbellularia californica, (CNDDB 2017, CNPS 2017); Pinus sabiniana is an associate in one of the southermost stands (Hoover 1970). Elevation 183–1555 m (generally > 500 m; with more than half of distribution > 1000 m) (Talley 1974, Farjon 2010). An Abies bracteata Forest Alliance is described in the Manual for California Vegetation Online (CNPS 2017) in areas where the fir has > 30% relative cover when co-dominant with Quercus chrysolepis. -

Santiago Fire

Basin-Indians Fire Basin Complex CA-LPF-001691 Indians Fire CA-LPF-001491 State Emergency Assessment Team (SEAT) Report DRAFT Affecting Watersheds in Monterey County California Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………… Team Members ………………………………………………………………………… Contacts ………………………………………………………..…………………….… Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. Summary of Technical Reports ……………………………………..………………. Draft Technical Reports ……………………………………………………..…………..…… Geology ……………………………………………………………………...……….… Hydrology ………………………………………………………………………………. Soils …………………………………………………………………………………….. Wildlife ………………………………………………………………….………………. Botany …………………………………………………………………………………... Marine Resources/Fisheries ………………………………………………………….. Cultural Resources ………………………………………………………..…………… List of Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………… Hazard Location Summary Sheet ……………………………………………………. Burn Soil Severity Map ………………………………………………………………… Land Ownership Map ……………………………………………………..…………... Contact List …………………………………………………………………………….. Risk to Lives and Property Maps ……………………………………….…………….. STATE EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT TEAM (SEAT) REPORT The scope of the assessment and the information contained in this report should not be construed to be either comprehensive or conclusive, or to address all possible impacts that might be ascribed to the fire effect. Post fire effects in each area are unique and subject to a variety of physical and climatic factors which cannot be accurately predicted. The information in this report was developed from cursory field -

California Partners in Flight the USDA Forest Service Klamath Bird Observatory and PRBO Conservation Science

The Coniferous Forest Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coniferous Forest Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 1.1 March 2002 A project of California Partners in Flight The USDA Forest Service Klamath Bird Observatory and PRBO Conservation Science Conservation Plan Lead Authors: John C. Robinson, USDA Forest Service John Alexander, Klamath Bird Observatory Conservation Plan Supporting Authors, PRBO Conservation Science: Sue Abbott Diana Humple Grant Ballard Melissa Pitkin Dan Barton Sandy Scoggin Gregg Elliott Diana Stralberg Sacha Heath Focal Species Account Authors: Black-backed Woodpecker – Kerry Farris Black-throated Gray Warbler – Tina Mark, USDA Forest Service Brown Creeper – Danielle LeFer, San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory Dark-eyed Junco – Jim DeStaebler, PRBO Conservation Science Flammulated Owl – Susan Yasuda, USDA Forest Service Fox Sparrow – Anne King, EDAW, Inc. Golden-crowned Kinglet – John C. Robinson, USDA Forest Service MacGillivray's Warbler – Chris Otahal, USDA Forest Service Olive-sided Flycatcher – Paul Brandy, Endangered Species Recovery Program Pileated Woodpecker – John C. Robinson, USDA Forest Service Red-breasted Nuthatch – Tina Mark and John C. Robinson, USDA Forest Service Vaux's Swift – John Sterling, Jones and Stokes Associates Western Tanager – Cory Davis, USDA Forest Service Financial Contributors: USDA Forest Service Packard Foundation National Fish and Wildlife Foundation PRBO Conservation Science Klamath Bird Observatory Acknowledgements: California Partners in Flight wishes to thank everyone who helped write, promote, and produce this document. Special thanks to Laurie Fenwood, Geoffrey Geupel, Aaron Holmes, Genny Wilson, Ryan Burnett, and Doug Wallace, and to Sophie Webb for her cover illustration. Recommended Citation: CalPIF (California Partners in Flight). 2002. -

Abies Bracteata Revised 2011 1 Abies Bracteata (D. Don) Poit

Lead Forest: Los Padres National Forest Forest Service Endemic: No Abies bracteata (D. Don) Poit. (bristlecone fir) Known Potential Synonym: Abies venusta (Douglas ex Hook.) K. Koch; Pinus bracteata D. Don; Pinus venusta Douglas ex Hook (Tropicos 2011). Table 1. Legal or Protection Status (CNDDB 2011, CNPS 2011, and Other Sources). Federal Listing Status; State Heritage Rank California Rare Other Lists Listing Status Plant Rank None; None G2/S2.3 1B.3 USFS Sensitive Plant description: Abies bracteata (Pinaceae) (Fig. 1) is a perennial monoecious plant with trunks longer than 55 m and less than 1.3 m wide. The branches are more-or-less drooping, and the bark is thin. The twigs are glabrous, and the buds are 1-2.5 cm long, sharp-pointed, and non- resinous. The leaves are less than 6 cm long, are dark green, faintly grooved on their upper surfaces, and have tips that are sharply spiny. Seed cones are less than 9 cm long with stalks that are under15 mm long. The cones have bracts that are spreading, exserted, and that are 1.5–4.5 cm long with a slender spine at the apex. Taxonomy: Abies bracteata is a fir species and a member of the pine family (Pinaceae). Out of the fir species growing in North America (Griffin and Critchfield 1976), Abies bracteata has the smallest range and is the least abundant. Identification: Many features of A. bracteata can be used to distinguish this species from other conifers, including the sharp-tipped needles, thin bark, club-shaped crown, non-resinous buds, and exserted spine tipped bracts (Gymnosperms Database 2010). -

The Spanish and Mexican Baseline of California Tree and Shrubland Distributions Since the Late 18Th Century

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 4 2015 The pS anish and Mexican Baseline of California Tree and Shrubland Distributions Since the Late 18th Century Richard A. Minnich University of California, Riverside Brett R. Goforth California State University, San Bernardino Richard Minnich Dept. of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Minnich, Richard A.; Goforth, Brett R.; and Minnich, Richard (2015) "The pS anish and Mexican Baseline of California Tree and Shrubland Distributions Since the Late 18th Century," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol33/iss1/4 Aliso, 33(1), pp. 5–76 ISSN 0065-6275 (print), 2327-2929 (online) THE SPANISH AND MEXICAN BASELINE OF CALIFORNIA TREE AND SHRUBLAND DISTRIBUTIONS SINCE THE LATE 18TH CENTURY RICHARD A. MINNICH1,3 AND BRETT R. GOFORTH2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California 92521; 2Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, California State University, San Bernardino, California 92407 3Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Historical distributions of 31 tree species, chaparral, and coastal sage scrub described by Spanish land explorers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (1769–1806) and in land grant disen˜os (1784– 1846) are reconstructed at 634 localities across central and southern California. This baseline predates most formal botanical surveys by nearly a century, allowing for assessment of vegetation change over the broadest time frame for comparison with pre-historical evidences and future distributions. -

TRIBUTARY TRIBUNE Stories and Art by Members of the California Conservation Corps Watershed Stewards Program, in Partnership with Americorps

Volume 25, Issue 1 TRIBUTARY TRIBUNE Stories and Art by Members of the California Conservation Corps Watershed Stewards Program, in partnership with AmeriCorps Year 25, District D “My comic comments on humanity’s current situation. We are faced with overwhelming environmental problems. Sometimes the good fight can seem hopeless—like a single fish looking for answers in an infinite ocean. But at the end of the day, real solutions start with just a single fish! Thanks for reading! - David Lopez-Portillo Las “Extrambólicas” Aventuras de D.L.P. Un Pez en el Hondo Translation David Lopez-Portillo, Placed at Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District Section 1: The “Outlandish” Adventures of D.L.P., One Fish in the Deep. “Extrambólicas” is actually a family inside joke, it isn’t a real word. My grandfather once described one of his travels as “extrambólico” and my mom wouldn’t let it go. Estrambótico, the closest word, translates to “outlandish”. Comic designed by Member David Lopez-Portillo of US-LT RCD. Story continued on page 2 A program of the California Conservation Corps, WSP is one of the most productive programs for future employment in natural resources. WSP is administered by California Volunteers and sponsored by the Corporation for National and Community Service. Watershed Stewards Program—Tributary Tribune The Land You Stand On Las “Extrambólicas” Maddy Luthard, Placed at Central Coast Wetlands Group Aventuras de D.L.P. Un Pez en el Hondo, As Watershed Stewards, many of us moved from across the state, or continued from page 1. even across the country, to engage in stewardship of ecosystems and watersheds that are not our own.