John Obrycki Jr. Academic Research Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaging in the Legislative Process

Engaging in the Legislative Process ISAC Legislative Team “I’m Just a Bill” • Idea . Government agencies, • Non-profits (i.e., ISAC) • Interest groups • You 2 Legislative Request Form The Legislative Policy Request Form is to be filled out by affiliates or individual members of ISAC. The form is the official avenue through which proposals are brought to the full ISAC Legislative Policy Committee to be considered as priorities during the 2017 legislative session. • Found on the ISAC website under Legislative Policy Committee • Fill out completely • Forward to affiliate legislative committee • And ISAC Legislative Policy Committee (LPC) • Chaired by ISAC Second Vice President o Lonny Pulkrabek, Johnson County Sheriff • 32 members (two from each affiliate) • Develop legislative objectives for ISAC’s policy team to pursue for the upcoming session • Meet in August and September to develop legislative platform Legislative Policy Committee (LPC) • Assessors: Dale McCrea & Deb McWhirter • Auditors: Ken Kline & Dennis Parrott • Community Services: Lori Elam & Shane Walter • Conservation: Dan Cohen & Matt Cosgrove • County Attorneys: Darin Raymond & Matt Wilbur • Emergency Mangement: Thomas Craighton & Dave Wilson • Engineers: Lyle Brehm & Dan Eckert • Environmental Health: Eric Bradley & Brian Hanft • Information Technology: Micah Cutler & Jeff Rodda • Public Health: Doug Beardsley & Lynelle Diers • Recorders: Megan Clyman & Kris Colby • Sheriffs & Deputies: Jay Langenbau & Jared Schneider • Supervisors: Carl Mattes & Burlin Matthews • Treasurers: Terri Kness & Tracey Marshall • Veterans Affairs: Gary Boseneiler & Chris Oliver • Zoning: Joe Buffington & Josh Busard ISAC Legislative Process • LPC develops policy statements and legislative objectives • Policy Statements express long-term or continuing statements of principle important for local control, local government authority, and efficient county operation. -

The Iowa Bystander

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years Sally Steves Cotten Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cotten, Sally Steves, "The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years" (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16720. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iowa Bystander: A history of the first 25 years by Sally Steves Cotten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1983 Copyright © Sally Steves Cotten, 1983 All rights reserved 144841,6 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE EARLY YEARS 13 III. PULLING OURSELVES UP 49 IV. PREJUDICE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA 93 V. FIGHTING FOR DEMOCRACY 123 VI. CONCLUSION 164 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 175 VIII. APPENDIX A STORY AND FEATURE ILLUSTRATIONS 180 1894-1899 IX. APPENDIX B ADVERTISING 1894-1899 182 X. APPENDIX C POLITICAL CARTOONS AND LOGOS 1894-1899 184 XI. -

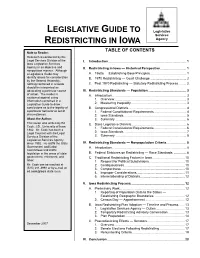

Legislative Guide to Redistricting in Iowa

LEGISLATIVE GUIDE TO Legislative Services REDISTRICTING IN IOWA Agency TABLE OF CONTENTS Note to Reader: Research is conducted by the Legal Services Division of the I. Introduction....................................................................................... 1 Iowa Legislative Services Agency in an objective and II. Redistricting in Iowa — Historical Perspective............................. 1 nonpartisan manner. Although a Legislative Guide may A. 1960s — Establishing Base Principles. ....................................... 1 identify issues for consideration B. 1970 Redistricting — Court Challenge. ....................................... 2 by the General Assembly, nothing contained in a Guide C. Post 1970 Redistricting — Statutory Redistricting Process......... 2 should be interpreted as advocating a particular course III. Redistricting Standards — Population. ......................................... 3 of action. The reader is A. Introduction. ................................................................................. 3 cautioned against using 1. Overview................................................................................ 3 information contained in a Legislative Guide to draw 2. Measuring Inequality. ............................................................ 3 conclusions as to the legality of B. Congressional Districts. ............................................................... 4 a particular behavior or set of 1. Federal Constitutional Requirements.................................... 4 circumstances. -

Nitrate Load Reduction Strategies for the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers

Nitrate Load Reduction Strategies for the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers Keith Schilling, Calvin Wolter Iowa DNR – Geological and Water Survey Outline of Presentation • Background of nitrate impairments • Nitrate reductions required by TMDL • SWAT modeling scheme • Nitrate reduction strategies evaluated for: i) Raccoon River and ii) Des Moines River • Concluding remarks • Acknowledgements: Phil Gassman and Manoj Jha, CARD, Iowa State; Allen Bonini, Watershed Improvement Section, Iowa DNR Raccoon and DSM rivers as a drinking water source Des Moines Water Works is a public water supply serving Des Moines metropolitan area of 400,000 people DMWW source water includes surface water collected directly from the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers Water sources are designated as Class “C” as a raw water source of potable water supply so drinking water standards are applicable The applicable water quality standard for nitrate for Class “C” designated use is the USEPA maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 10 mg/l. Drinking water or Gulf of Mexico hypoxia….still nitrate Impaired segments Watershed Characteristics Nitrate impairment – Raccoon River Flow Max. Load Maximum % of Days Mean Max. Mean Mean Point 100040000 Range Flow in Exceedance Reduction Needing Reduction Nitrate9.5 mg/l NPS Source Range 35000Factor 1 Needed Reduction Needed Load Contrib. Contrib. (cfs) 30000 (%)2 (%)2 (Mg)10mg/l (%)3 (%)3 100-90 35700 25000 1.93 48.1 52.1 24.4 584.1Measured 97.8 N load 2.2 90-80 5070100 20000 1.89 47.0 64.7 25.4 202.0 95.5 4.5 80-70 2730 15000 1.89 46.6 57.5 -

2017 National Forum on Education Policy Roster of Participants

2017 National Forum on Education Policy Roster of Participants *LAST UPDATED JUNE 28, 2017* ALABAMA Christian Becraft Alabama Governor's Office Stephanie Bell Alabama State Board of Education Jennifer Brown Alabama Department of Education Ryan Cantrell American Federation for Children Dana Jacobson 2017 Alabama Teacher of the Year / Clay-Chalkville High School Jeff Langham Alabama State Dept of Education Eric Mackey School Superintendents of Alabama Tracey Meyer Alabama State Dept of Education Allison Muhlendorf Alabama School Readiness Alliance Jeana Ross Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education Sally Smith Alabama Association of School Boards Kelisa Wing Department of Defense Education Activity Lisa Woodard School Superintendents of Alabama ALASKA Harriet Drummond Alaska House of Representatives James Fields Alaska Board of Education and Early Development James Harris Alaska DEED Michael Johnson State of Alaska, Department of Education and Early Development Kathy Moffitt Anchorage School District Nancy Norman Norman Consultant Services Gary Stevens Alaska State Senate Patricia Walker Alaska Legislature AMERICAN SAMOA Dana Love-Ili American Samoa Department of Education ARIZONA Catcher Baden Arizona State Legislature Jennifer Dane The Ohio State University Michelle Doherty Arizona Educational Foundation/Encanto School Pearl Esau Expect More Arizona Rebecca Hill A for Arizona Paul Koehler WestEd 700 Broadway, Suite 810 • Denver, CO 80203-3442 • 303.299.3600 • Fax: 303.296.8332 | www.ecs.org | @EdCommission Janice Palmer Helios -

2020 Legislative Preview: Iowa Legislators Share Agendas for Upcoming Session

January 2020 2020 LEGISLATIVE PREVIEW: IOWA LEGISLATORS SHARE AGENDAS FOR UPCOMING SESSION MATT WINDSCHITL, House Majority Leader PAT GRASSLEY, House Speaker-select A CUSTOM PUBLICATION FOR ABI IOWA ASSOCIATION OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS OF ASSOCIATION IOWA TRUST US TO HELP DRIVE YOUR BUSINESS Our auto service and repair shop package is driven by shops’ specialized needs. From equipment and wash bay protection to garage liability coverage, our insurance kicks into gear when it’s needed most, so you can focus on getting customers back on the road. Trust in Tomorrow.® Contact us today. AUTO | HOME | FARM | BUSINESS January 2020 January | | IOWA grinnellmutual.com “Trust in Tomorrow.” and the “Grinnell Mutual” are registered trademarks of Grinnell Mutual Reinsurance Company. © Grinnell Mutual Reinsurance Company, 2020. Business Record Record Business 2 A CUSTOM PUBLICATION FOR ABI IN PARTNERSHIP WITH A VIEW FROM THE TOP JANUARY 2020 VOLUME 10 | NUMBER 1 Leading Organizations are Always Looking Ahead 2019 was a busy and successful year at ABI, but leading organizations are always looking ahead, putting their future in focus. One of the things to which ABI is looking ahead is the 2020 session of the Iowa General Assembly. This edition of Business Record Iowa highlights INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS OF ASSOCIATION IOWA the upcoming session and issues that will be considered by the Iowa Legislature this year. At Collins Aerospace (and at other ABI companies), our people make some of the highest- quality and most innovative products in the world. We share that story with elected officials at every opportunity. We know our legislators, and we invite them into our plant often. -

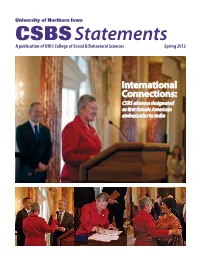

Csbsstatements

University of Northern Iowa CSBS Statements A publication of UNI’s College of Social & Behavioral Sciences Spring 2012 International Connections: CSBS alumna designated as first female American ambassador to India In this issue: Greetings from Hong Kong 2 Textile & Apparel alumna finds success working and living abroad Alumni Connections 5 Alumna helps student find a unique opportunity A Diplomatic Mission 6 History alumna dedicated to the service of her country Keeping up with Rhonda 7 Recent graduate is off to a great start already Back to School 8 UNI grads who returned as great faculty Thank You 10 Alumni and friends who have helped make our college stronger Why We’re Here 13 A note from our Director of Development Cover: The Honorable Nancy J. Powell, College & Department Briefs the first female American 14 A quick look at the year’s news ambassador to India, is a UNI history alumna. Student News See page 6 16 CSBS students continue to shine Faculty Briefs 18 Our faculty excel in teaching, research, and service Alumni Updates 20 See what other CSBS alumni are doing—and be in our next edition CSBS Statements Thanks to those who provided additional photos for CSBS Statements— Volume 14 Spring 2012 cover: University Relations, Patricia Geadelmann; pp2-4: Melissa Ilg; p5: Mitchell Strauss; p6: University Relations, Patricia Geadelmann; p7: Rhonda CSBS Statements is published annually Greenway; p8: Elaine Eshbaugh; p9: Andrey Petrov; p12: Kevin Boatright; p15: by the College of Social and Behavioral University Relations, Dan Ozminkowski, Annette Lynch; pp16-17: University Sciences at the University of Northern Relations; pp18-19: courtesy photo Iowa for its alumni and friends. -

The Annals of Iowa

The Annals of Volume 79, Number 1 Iowa Winter 2020 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue ANDREW KLUMPP describes the founding of the Dutch colony in Sioux County and the efforts of the Dutch settlers to seize and maintain control of county politics. They were able to do so, he argues, because they effectively navigated U.S. political culture while prioritizing the needs of their ethnic colony over partisan politics. SHARON ROMEO assesses five Iowa Supreme Court cases from 1865 to 1879 that addressed Iowa’s criminal seduction statute. She shows how the court’s interpretation of Iowa’s criminal seduction laws promoted a concept of gendered citizenship—the legal logic that demanded that men and wom- en be allocated the rights and obligations of citizenship based on their sex. JASON SHURLEY narrates the career of C. H. McCloy, focusing on the research he did at the University of Iowa that questioned the assumption that weight training would make athletes slow and “muscle bound.” Shurley concludes that the work done by McCloy and his students and colleagues at the University of Iowa was instrumental in establishing the importance of weight training for successful athletes. Front Cover University of Iowa swimmer Charles Mitchell in the 1950s works out with weights to train for his events. Photo courtesy of York Barbell Company. For an account of University of Iowa researcher C. H. McCloy’s role in establishing the viability of weight training for athletes, see Jason Shurley’s article in this issue. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. -

Roster Executive Committee 2019-20

ROSTER EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2019-20 NCSL OFFICERS President Staff Chair Speaker Robin Vos Martha R. Wigton Assembly Speaker Director – House Budget & Research Wisconsin Legislature Office State Capitol, Room 217 West Georgia General Assembly PO Box 8953 412 Coverdell Legislative Office Building Madison, WI 53708-8953 18 Capitol Square (608) 266-9171 Atlanta, GA 30334 [email protected] (404) 656-5050 [email protected] President-Elect Staff Vice Chair Speaker Scott Saiki Joseph James “J.J.” Gentry, Esq. Speaker of the House Counsel, Ethics Committee – Senate Hawaii State Legislature South Carolina General Assembly State Capitol PO Box 142 415 South Beretania Street, Room 431 205 Gressette Building Honolulu, HI 96813 Columbia, SC 29202 (808) 586-6100 (803) 212-6306 [email protected] [email protected] Vice President Immediate Past Staff Chair Speaker Scott Bedke Jon Heining Speaker of the House General Counsel – Legislative Council Idaho Legislature Texas Legislature State Capitol Building PO Box 12128 PO Box 83720 Robert E. Johnson Building 700 West Jefferson Street 1501 North Congress Avenue Boise, ID 83720-0038 Austin, TX 78711-2128 (208) 332-1123 (512) 463-1151 [email protected] [email protected] Executive Committee Roster 2019-20 ROSTER EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Immediate Past President Speaker Mitzi Johnson Speaker of the House Vermont General Assembly State House 115 State Street Montpelier, VT 05633-5501 (802) 828-2228 [email protected] AT LARGE MEMBERS Representative -

Filling US Senate Vacancies

Filling U.S. Senate Vacancies: Perspectives and Contemporary Developments Thomas H. Neale Specialist in American National Government March 10, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40421 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Filling U.S. Senate Vacancies: Perspectives and Contemporary Developments Summary The presidential election of 2008 resulted, directly and indirectly, in the highest number of Senate vacancies associated with a presidential transition period in more than 60 years. The election of incumbent Senators as President and Vice President, combined with subsequent cabinet appointments, resulted in four Senate vacancies, in Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, and New York, all states in which the governor is empowered to appoint a temporary replacement. Protracted controversies surrounding the replacement process in two of these states drew scrutiny and criticism not only of the particular circumstances, but of the temporary appointment process itself. While the process of appointing temporary replacements to fill Senate vacancies has come under examination since the presidential election, the practice itself is as old as the Constitution, having been incorporated in the original document by the founders at the Constitutional Convention. The practice was revised by the 17th Amendment, which became effective in 1913. The amendment’s primary purpose was to substitute direct popular election of Senators for the original provision of election by state legislatures, but it also changed -

Raccoon River Watershed Water Quality Master Plan

• • • Raccoon River Watershed Water Quality Master Plan November 2011 A tool to inform and guide watershed residents and stakeholders as they seek to cooperatively improve water quality in Iowa’s Raccoon River Watershed. 1 | Page Raccoon River Watershed Water Quality Master Plan • • • Thank you to the many stakeholders, experts, and diverse interests who contributed to development of the recommendations and ideas expressed in this document. Without your time, your assistance, and your honest opinions, development of the Master Plan would not have been possible. Special thanks to Drs. Phil Gassman and Manoj Jha, Center for Agriculture and Rural Development, for your leadership and work on water quality modeling. Prepared on behalf of the M&M Divide Resource Conservation & Development By Agren, Inc. Carroll, IA This report is designed for general information only. Although the information contained herein is believed to be correct and reflective of stakeholder interests, M&M Divide and Agren assume no liability whatsoever in connection with the use of the contents of the report by any person. Copyright 2011 Agren, Inc. All rights reserved. Raccoon River Watershed Water Quality Master Plan • • • Raccoon River Watershed Water What is a watershed? Quality Master • • • Plan The term watershed refers to an area of November 2011 land that all drains to a common Preface waterway. The watershed area includes both the The Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) streams and rivers awarded a grant to the Missouri & Mississippi (M&M) that convey water, Divide RC&D, with a subcontract to Agren, Inc. to as well as the land develop a Water Quality Master Plan for the Raccoon surfaces from which River Watershed in January 2010. -

Evaluation of Variation in Nitrate Concentration Levels in the Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2012 Evaluation of Variation in Nitrate Concentration Levels in the Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa Sampath Jayasinghe Decision Innovation Solutions, [email protected] David Miller Iowa Farm Bureau Federation Jerry L. Hatfield USDA-ARS, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Jayasinghe, Sampath; Miller, David; and Hatfield, Jerry L., "Evaluation of Variation in Nitrate Concentration Levels in the Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa" (2012). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 1368. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/1368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal of Environmental Quality TECHNICALTECHNICAL REPORTS REPORTS SURFACE WATER QUALITY Evaluation of Variation in Nitrate Concentration Levels in the Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa Sampath Jayasinghe,* David Miller, and Jerry L. Hatfi eld he Raccoon River Watershed (RRW) in Iowa Th e Raccoon River Watershed in Iowa has received considerable has received considerable attention in recent years due to attention in the recent past due to frequent detections of nitrate − concentrations above the federal drinking water standard.