Filling US Senate Vacancies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaging in the Legislative Process

Engaging in the Legislative Process ISAC Legislative Team “I’m Just a Bill” • Idea . Government agencies, • Non-profits (i.e., ISAC) • Interest groups • You 2 Legislative Request Form The Legislative Policy Request Form is to be filled out by affiliates or individual members of ISAC. The form is the official avenue through which proposals are brought to the full ISAC Legislative Policy Committee to be considered as priorities during the 2017 legislative session. • Found on the ISAC website under Legislative Policy Committee • Fill out completely • Forward to affiliate legislative committee • And ISAC Legislative Policy Committee (LPC) • Chaired by ISAC Second Vice President o Lonny Pulkrabek, Johnson County Sheriff • 32 members (two from each affiliate) • Develop legislative objectives for ISAC’s policy team to pursue for the upcoming session • Meet in August and September to develop legislative platform Legislative Policy Committee (LPC) • Assessors: Dale McCrea & Deb McWhirter • Auditors: Ken Kline & Dennis Parrott • Community Services: Lori Elam & Shane Walter • Conservation: Dan Cohen & Matt Cosgrove • County Attorneys: Darin Raymond & Matt Wilbur • Emergency Mangement: Thomas Craighton & Dave Wilson • Engineers: Lyle Brehm & Dan Eckert • Environmental Health: Eric Bradley & Brian Hanft • Information Technology: Micah Cutler & Jeff Rodda • Public Health: Doug Beardsley & Lynelle Diers • Recorders: Megan Clyman & Kris Colby • Sheriffs & Deputies: Jay Langenbau & Jared Schneider • Supervisors: Carl Mattes & Burlin Matthews • Treasurers: Terri Kness & Tracey Marshall • Veterans Affairs: Gary Boseneiler & Chris Oliver • Zoning: Joe Buffington & Josh Busard ISAC Legislative Process • LPC develops policy statements and legislative objectives • Policy Statements express long-term or continuing statements of principle important for local control, local government authority, and efficient county operation. -

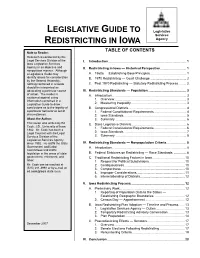

Legislative Guide to Redistricting in Iowa

LEGISLATIVE GUIDE TO Legislative Services REDISTRICTING IN IOWA Agency TABLE OF CONTENTS Note to Reader: Research is conducted by the Legal Services Division of the I. Introduction....................................................................................... 1 Iowa Legislative Services Agency in an objective and II. Redistricting in Iowa — Historical Perspective............................. 1 nonpartisan manner. Although a Legislative Guide may A. 1960s — Establishing Base Principles. ....................................... 1 identify issues for consideration B. 1970 Redistricting — Court Challenge. ....................................... 2 by the General Assembly, nothing contained in a Guide C. Post 1970 Redistricting — Statutory Redistricting Process......... 2 should be interpreted as advocating a particular course III. Redistricting Standards — Population. ......................................... 3 of action. The reader is A. Introduction. ................................................................................. 3 cautioned against using 1. Overview................................................................................ 3 information contained in a Legislative Guide to draw 2. Measuring Inequality. ............................................................ 3 conclusions as to the legality of B. Congressional Districts. ............................................................... 4 a particular behavior or set of 1. Federal Constitutional Requirements.................................... 4 circumstances. -

2017 National Forum on Education Policy Roster of Participants

2017 National Forum on Education Policy Roster of Participants *LAST UPDATED JUNE 28, 2017* ALABAMA Christian Becraft Alabama Governor's Office Stephanie Bell Alabama State Board of Education Jennifer Brown Alabama Department of Education Ryan Cantrell American Federation for Children Dana Jacobson 2017 Alabama Teacher of the Year / Clay-Chalkville High School Jeff Langham Alabama State Dept of Education Eric Mackey School Superintendents of Alabama Tracey Meyer Alabama State Dept of Education Allison Muhlendorf Alabama School Readiness Alliance Jeana Ross Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education Sally Smith Alabama Association of School Boards Kelisa Wing Department of Defense Education Activity Lisa Woodard School Superintendents of Alabama ALASKA Harriet Drummond Alaska House of Representatives James Fields Alaska Board of Education and Early Development James Harris Alaska DEED Michael Johnson State of Alaska, Department of Education and Early Development Kathy Moffitt Anchorage School District Nancy Norman Norman Consultant Services Gary Stevens Alaska State Senate Patricia Walker Alaska Legislature AMERICAN SAMOA Dana Love-Ili American Samoa Department of Education ARIZONA Catcher Baden Arizona State Legislature Jennifer Dane The Ohio State University Michelle Doherty Arizona Educational Foundation/Encanto School Pearl Esau Expect More Arizona Rebecca Hill A for Arizona Paul Koehler WestEd 700 Broadway, Suite 810 • Denver, CO 80203-3442 • 303.299.3600 • Fax: 303.296.8332 | www.ecs.org | @EdCommission Janice Palmer Helios -

2020 Legislative Preview: Iowa Legislators Share Agendas for Upcoming Session

January 2020 2020 LEGISLATIVE PREVIEW: IOWA LEGISLATORS SHARE AGENDAS FOR UPCOMING SESSION MATT WINDSCHITL, House Majority Leader PAT GRASSLEY, House Speaker-select A CUSTOM PUBLICATION FOR ABI IOWA ASSOCIATION OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS OF ASSOCIATION IOWA TRUST US TO HELP DRIVE YOUR BUSINESS Our auto service and repair shop package is driven by shops’ specialized needs. From equipment and wash bay protection to garage liability coverage, our insurance kicks into gear when it’s needed most, so you can focus on getting customers back on the road. Trust in Tomorrow.® Contact us today. AUTO | HOME | FARM | BUSINESS January 2020 January | | IOWA grinnellmutual.com “Trust in Tomorrow.” and the “Grinnell Mutual” are registered trademarks of Grinnell Mutual Reinsurance Company. © Grinnell Mutual Reinsurance Company, 2020. Business Record Record Business 2 A CUSTOM PUBLICATION FOR ABI IN PARTNERSHIP WITH A VIEW FROM THE TOP JANUARY 2020 VOLUME 10 | NUMBER 1 Leading Organizations are Always Looking Ahead 2019 was a busy and successful year at ABI, but leading organizations are always looking ahead, putting their future in focus. One of the things to which ABI is looking ahead is the 2020 session of the Iowa General Assembly. This edition of Business Record Iowa highlights INDUSTRY AND BUSINESS OF ASSOCIATION IOWA the upcoming session and issues that will be considered by the Iowa Legislature this year. At Collins Aerospace (and at other ABI companies), our people make some of the highest- quality and most innovative products in the world. We share that story with elected officials at every opportunity. We know our legislators, and we invite them into our plant often. -

Roster Executive Committee 2019-20

ROSTER EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2019-20 NCSL OFFICERS President Staff Chair Speaker Robin Vos Martha R. Wigton Assembly Speaker Director – House Budget & Research Wisconsin Legislature Office State Capitol, Room 217 West Georgia General Assembly PO Box 8953 412 Coverdell Legislative Office Building Madison, WI 53708-8953 18 Capitol Square (608) 266-9171 Atlanta, GA 30334 [email protected] (404) 656-5050 [email protected] President-Elect Staff Vice Chair Speaker Scott Saiki Joseph James “J.J.” Gentry, Esq. Speaker of the House Counsel, Ethics Committee – Senate Hawaii State Legislature South Carolina General Assembly State Capitol PO Box 142 415 South Beretania Street, Room 431 205 Gressette Building Honolulu, HI 96813 Columbia, SC 29202 (808) 586-6100 (803) 212-6306 [email protected] [email protected] Vice President Immediate Past Staff Chair Speaker Scott Bedke Jon Heining Speaker of the House General Counsel – Legislative Council Idaho Legislature Texas Legislature State Capitol Building PO Box 12128 PO Box 83720 Robert E. Johnson Building 700 West Jefferson Street 1501 North Congress Avenue Boise, ID 83720-0038 Austin, TX 78711-2128 (208) 332-1123 (512) 463-1151 [email protected] [email protected] Executive Committee Roster 2019-20 ROSTER EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Immediate Past President Speaker Mitzi Johnson Speaker of the House Vermont General Assembly State House 115 State Street Montpelier, VT 05633-5501 (802) 828-2228 [email protected] AT LARGE MEMBERS Representative -

Council of State Governments Capitol

THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS SEPT 2011 CAPITOL RESEARCH SPECIAL REPORT Public Access to Official State Statutory Material Online Executive Summary As state leaders begin to realize and utilize the incredible potential of technology to promote trans- parency, encourage citizen participation and bring real-time information to their constituents, one area may have been overlooked. Every state provides public access to their statutory material online, but only seven states—Arkansas, Delaware, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, Utah and Vermont—pro- vide access to official1 versions of their statutes online. This distinction may seem academic or even trivial, but it opens the door to a number of questions that go far beyond simply whether or not a resource has an official label. Has the information online been altered—in- tentionally or not—from its original form? Who is in March:2 “You’ve often heard it said that sunlight is responsible for mistakes? How often is it updated? the best disinfectant. And the recognition is that, for Is the information secure? If the placement of a re- us to do better, it’s critically important for the public source online is not officially mandated or approved to know what we’re doing.” by a statute or rule, its reliability and accuracy are At the most basic level, free and open public access difficult to gauge. to the law that governs this country—federal and As state leaders have moved quickly to provide state—is necessary to create the transparency that is information electronically to the public, they may fundamental to a functional participatory democracy. -

John Obrycki Jr. Academic Research Project

Broadening the Communities to Which We Belong: Iowa, Agriculture, and the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture by John F. Obrycki BROADENING THE COMMUNITIES TO WHICH WE BELONG: IOWA, AGRICULTURE, AND THE LEOPOLD CENTER Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by John F. Obrycki Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 APPROVED Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Hays Cummins BROADENING THE COMMUNITIES TO WHICH WE BELONG: IOWA, AGRICULTURE, AND THE LEOPOLD CENTER A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History by John F. Obrycki Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 APPROVED Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Kevin C. Armitage Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Hays Cummins Reader ____________________________ Dr. William Newell Accepted by ___________________________ Director, University Honors Program Dr. Mary E. Frederickson ii BROADENING THE COMMUNITIES TO WHICH WE BELONG: IOWA, AGRICULTURE, AND THE LEOPOLD CENTER A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by John F. Obrycki Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 APPROVED Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Kevin C. Armitage Advisor ___________________________ Dr. Hays Cummins Reader ____________________________ Dr. William Newell Accepted by ___________________________ -

50 State Report Card Tracking Eminent Domain Reform

50state report card Tracking Eminent Domain Reform Legislation since Kelo August 2007 1 Synopsis 5 Alabama . .B+ 6 Alaska . .D 7 Arizona . .B+ 8 Arkansas . .F 9 California . .D- 10 Colorado . .C 11 Connecticut . .D 12 Delaware . .D- 13 Florida . .A 14 Georgia . .B+ 15 Hawaii . .F 16 Idaho . .D+ 17 Illinois . .D+ 18 Indiana . .B 19 Iowa . .B- 20 Kansas . .B 21 Kentucky . .D+ 22 Louisiana . .B 23 Maine . .D+ 24 Maryland . .D 25 Massachusetts . .F 26 Michigan . .A- 27 Minnesota . .B- 28 Mississippi . .F 29 Missouri . .D table of contents & state grades 30 Montana . .D 31 Nebraska . .D+ 32 Nevada . .B+ 33 New Hampshire . .B+ 34 New Jersey . .F 35 New Mexico . .A- 36 New York . .F 37 North Carolina . .C- 38 North Dakota . .A 39 Ohio . .D 40 Oklahoma . .F 41 Oregon . .B+ 42 Pennsylvania . .B- 43 Rhode Island . .F 44 South Carolina . .B+ 45 South Dakota . .A 46 Tennessee . .D- 47 Texas . .C- 48 Utah . .B 49 Vermont . .D- 50 Virginia . .B+ 51 Washington . .C- 52 West Virginia . .C- 53 Wisconsin . .C+ 54 Wyoming . .B 50state50 reportstate card reportTracking Eminentcard Domain Tracking ReformEminent Legislation Domain since Kelo Abuse Legislation since Kelo I n the two years since the U.S. Supreme Court’s now-infamous decision in Kelo v. City of New London, 42 states have passed new laws aimed at curbing the abuse of eminent domain for private use. 50state report card Castle Coalition Given that significant reform on most issues takes years to accomplish, the horrible state of most eminent domain laws, and that the defenders of eminent domain abuse—cities, developers and planners—have flexed their considerable political muscle to preserve the status quo, this is a remarkable and historic response to the most reviled Supreme Court decision of our time. -

The Collapse of the Iowa Democratic Party: Iowa and the Lecompton Constitution Garret Wilson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 the collapse of the iowa democratic party: iowa and the lecompton constitution Garret Wilson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Garret, "the collapse of the iowa democratic party: iowa and the lecompton constitution" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12519. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12519 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The collapse of the Iowa Democratic Party: Iowa and the lecompton constitution by Garret W. Wilson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Kathleen Hilliard, Major Professor Charles Dobbs Robert Urbatsch Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Garret W. Wilson 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Early Development of Iowa 9 Chapter 2 The Lecompton Constitution 33 Chapter 3 The Lasting Effects of the Lecompton Constitution 58 Bibliography 79 1 Introduction The ideal of compromise consumed the politics of America during the antebellum era. The political arguments of expansion and abolition of slavery constantly threatened to tear the Union apart because with every piece of new legislation a state would threaten secession. -

3.12 -- Page 1 of 4 the THREE BRANCHES of GOVERNMENT

USA–Iowa TOOLKIT #3.12 -- Page 1 of 4 THE THREE BRANCHES OF GOVERNMENT https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/resources/threeBranchesGovernment.pdf In Iowa government, as at the national level of government, power is distributed among three branches: • Legislative – www.legis.iowa.gov – The legislative branch creates laws that establish policies and programs. • Executive – www.iowagov –The executive branch carries out the policies and programs contained in law. • Judicial – www.iowacourts.gov – The judicial branch resolves any conflicts arising from the interpretation or application of the laws. While each branch of government has its own separate responsibilities, one branch cannot function without the other two branches. LEGISLATIVE BRANCH: The Iowa Constitution establishes the state’s lawmaking authority in a general assembly consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The Iowa General Assembly is often referred to as the “Iowa Legislature” or simply the “Legislature.” Legislative Districts The Iowa Senate consists of 50 members. Each Senator represents a separate geographic area of the state. This area is called a district. There are 50 Senate districts in Iowa. Each Senate district currently contains approximately 58,500 people. The Iowa House of Representatives consists of 100 members. As with the Senate, each Representative serves a separate district. There are 100 House districts in Iowa, two within each Senate district. Currently, each House district contains approximately 29,300 people. Every Iowan is represented by one Senator and one Representative in the Iowa Legislature (also known as the General Assembly) Since the districts are all of nearly equal population, all Iowans are represented equally in the General Assembly. -

Iowa Mitigation Program Leads to $1.4 Billion in Flood Prevention Projects How the State Leveraged Federal Funding to Develop Mitigation Program

Brief Nov 2019 Mitigation Matters: Policy Solutions to Reduce Local Flood Risk This brief is one of 13 that examine state and local policies that have resulted in actions to mitigate flooding. Des Moines Water Works Floodwaters from the Raccoon River inundate the Des Moines Water Works, center left above, and other areas near downtown Des Moines, Iowa, in July 1993. Iowa Mitigation Program Leads to $1.4 Billion in Flood Prevention Projects How the state leveraged federal funding to develop mitigation program Overview In 2008, devastating floods across the Midwest left Iowa with an estimated $10 billion in damage. In Cedar Rapids alone, 5,200 homes were damaged or destroyed after two weeks of historic rainfall.1 As the state recovered, policymakers used some of the federal disaster assistance it received to create authorities tasked with reducing flood risk across watersheds—as opposed to a more localized, project-specific approach. The predominantly agricultural state later established a long-term funding source for communities seeking to mitigate damage from future floods. After years of flooding, state officials use federal aid to launch flood mitigation projects The 2008 flooding was not an isolated incident. Fifteen years earlier, Iowa and eight other states endured one of the 10 costliest disasters in U.S. history when the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and their tributaries spilled over their banks.2 The state has continued to experience frequent floods in the years since. From 2009 to 2018, Iowa was tied with Kentucky and West Virginia as the states with the most flood-related disaster declarations in the country.3 In the two years after the 2008 flood, Iowa received several rounds of disaster recovery funds from Congress. -

Fifth Iowa General Assembly Law to "Allow Meskwaki to Purchase Land and Live in Tama, Iowa," July 15, 1856

Fifth Iowa General Assembly Law to "Allow Meskwaki to Purchase Land and Live in Tama, Iowa," July 15, 1856 Acts, Resolutions and Memorials Passed at the Extra Session of the Fifth General Assembly of the State of Iowa, Which convened at Iowa City, on the Second day July, Anno Domini, 1856. James W. Grimes, Gov. Geo. W. McCleary, Sec. John Pattee, Auditor. M.L. Morris, Treasurer. Maturin L. Fisher, President of the Senate. Reuben Noble, Speaker of House of Representatives. Publisher by Authority Iowa City P. Moriarty, State Printer 1856 LAWS OF IOWA. Chapter 30. INDIANS. AN ACT permitting certain Indians to reside within the State. SECTION. 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Iowa, That the consent of the State is hereby given that the Indians now residing in Tama county known as a portion of the Sacs and Foxes, be permitted to remain and reside in said State, and that the Governor be requested to inform the Secretary of war thereof, and urge on said portion of the annuities due or to become due to said Tribe of Sacs and Fox Indians. Sec. 2. That the Sheriff of said county, shall as soon as a copy of this law is filed in the office of the County Court proceed to take the census of said Indians now residing there giving their names, and sex, which said list shall be filed and recorded in said office, the persons whose names are included in said list shall have the privileges granted under this act, but none others shall be considered as embraced within the provisions of said act.