Tavernier, a Filmmaker in His Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacques Prévert's Filmography

Jacques Prévert’s Filmo graphy Jacques Prévert has worked on more than a hundred of movies, yet his filmography remains underestimated. One counts about sixty films, short movies and full-length films, as well as about fifty written movies, in more or less accomplished stages: some are totally unpublished, the others had been written for directors having finally never shot them. Among the directed movies, some were so different from the initial scenario that Prévert refused to sign them. The non exhaustive filmography, which follows, presents only directed movies. The indicated year is that of the preceded French release, where necessary, that of the year of stake in production if there is more than a year of distance. Souvenir de Paris (1928), scriptwriter : Jacques Prévert, based on an idea of Pierre Prévert. Directors : Marcel Duhamel and Pierre Prévert. Baleydier (1931), author of the dialogues : Jacques Prévert, not credited. Scriptwriter : André Girard. Director : Jean Mamy. Ténérife (1932, short film, documentary), comment written by Jacques Prévert. Director : Yves Allégret. L’Affaire est dans le sac (1932, short film), scriptwriter, author of the adaptation and dialogues : Jacques Prévert. Director : Pierre Prévert. Bulles de savon (Seifenblasen, mute, Germany, 1933), comment of the French version written by Jacques Prévert. Scriptwriter and director : Slatan Dudow. Taxi de Minuit (1934, short film), based on the novel of Charles Radina. Scriptwriter, co-author of the adaptation (with Lilo Dammert) and author of the dialogues : Jacques Prévert. Director Albert Valentin. La Pêche à la baleine (1934, short film), interpretation by Jacques Prévert, based on his own text, written in 1933. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

Prêt-À-Porter (Film) 1 Prêt-À-Porter (Film)

Prêt-à-Porter (film) 1 Prêt-à-Porter (film) Prêt-à-Porter American theatrical promotional poster Directed by Robert Altman Produced by Robert Altman Scott Bushnell Written by Robert Altman Barbara Shulgasser Starring Marcello Mastroianni Sophia Loren Anouk Aimée Rupert Everett Julia Roberts Tim Robbins Kim Basinger Stephen Rea Forest Whitaker Richard E. Grant Lauren Bacall Lili Taylor Sally Kellerman Tracey Ullman Linda Hunt Teri Garr Danny Aiello Lyle Lovett Music by Michel Legrand Cinematography Jean Lépine Pierre Mignot Editing by Geraldine Peroni Suzy Elmiger Distributed by Miramax Films Release dates • December 23, 1994 Running time 133 minutes Country United States Language English French Italian Russian Spanish Box office $11,300,653 Prêt-à-Porter (English: Ready to Wear) is a 1994 American satirical comedy film co-written, directed, and produced by Robert Altman and shot during the Paris, France, Fashion Week with a host of international stars, models and designers. The film may be best known for its many cameo appearances and its final scene which features two minutes of nude female models walking the catwalk. Prêt-à-Porter (film) 2 Cast • Marcello Mastroianni as Sergei/Sergio • Sophia Loren as Isabella de la Fontaine • Anouk Aimée as Simone Lowenthal • Rupert Everett as Jack Lowenthal • Julia Roberts as Anne Eisenhower • Tim Robbins as Joe Flynn • Kim Basinger as Kitty Potter • Stephen Rea as Milo O'Brannigan • Forest Whitaker as Cy Bianco • Richard E. Grant as Cort Romney • Lauren Bacall as Slim Chrysler • Lyle Lovett as Clint -

Bertrand Tavernier's Coup De Torchon

N AHEM Y OUSAF A Southern Sheriff’s Revenge: Bertrand Tavernier’s Coup de Torchon This essay traces the story of a Texan small-town sheriff as first told and reworked by the American pulp fiction writer Jim Thompson in The Killer Inside Me (1952) and Pop. 1280 (1964), and transformed by French film director Bertrand Tavernier when he transposes this par- ticular ‘Southern’ sheriff’s story to colonial Senegal in 1938 in Coup de Torchon (Clean Slate, 1980). To begin, this essay considers why Thompson shifts his story from the American ‘West’ in the 1950s to the American ‘South’ in the 1960s before examining in some detail the ways in which Tavernier’s cross-cultural and trans-generic remake of Pop. 1280 successfully interrogates southern tropes in non-southern settings. The image of the Southern sheriff in twentieth-century fiction and film accrued mainly negative connotations, by focusing on the stakes sheriffs had in white supremacy and in maintaining a segregated sta- tus quo, or exploring their limited efforts to move beyond being either ineffectual or corrupt – or both. In novels such as Erskine Caldwell’s Trouble in July (1940) and Elizabeth Spencer’s The Voice at the Back Door (1956), for example, the small-town sheriff is mired in a moral dilemma. Spencer created Mississippi sheriff Duncan Harper while living in Italy. Thrust into office by the dying incumbent, he struggles against racist crimes that have been ignored in the past, the repercus- sions of which threaten the present. He dies having made a racially liberal plea to the town that after his death may choose to deem him merely eccentric. -

L'académie Des César Rend Hommage À Jean-Pierre

COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Paris, le 25 avril 2019 L’ACADÉMIE DES CÉSAR REND HOMMAGE À JEAN-PIERRE MARIELLE Un monument du cinéma français vient de nous quitter. Cette carrure massive et ce franc-parler, au travers d’une voix chaude et grave, avaient fait de lui l’un des acteurs les plus populaires du cinéma français. Jean-Pierre Marielle était aussi et surtout un formidable interprète, qui incarnait ses rôles avec cet humour piquant et un certain cynisme qui lui étaient si propres. Jean-Pierre Marielle s’est retrouvé dès son plus Jeune âge parmi les futurs grands noms du cinéma, s’inscrivant lui-même au sein de cette incroyable génération : Jean-Paul Belmondo, Annie Girardot, Claude Rich, Françoise Fabian ou Jean Rochefort, font partie de ses camarades de classe au Conservatoire de Paris. Il se tourne tout d’abord vers le théâtre, avec un premier rôle dans une pièce de Molière, Le Mariage forcé, en 1953. Au cinéma, en 1964, il est aux côtés de Louis de Funès dans Faites sauter la banque de Jean Girault, et de Jean-Paul Belmondo dans Week-end à Zuydcoote d’Henri Verneuil. En 1969, il est auprès d’Yves Montand dans Le diable par la queue de Philippe de Broca. La décennie suivante le consacre comme un acteur incontournable des films populaires : Sex-shop de Claude Berri, La Valise de Georges Lautner, Comment réussir quand on est con et pleurnichard de Michel Audiard, Calmos de Bertrand Blier, Cause toujours… tu m’intéresses ! d’Edouard Molinaro, … Jean-Pierre Marielle ne cesse de tourner tandis que des rôles plus dramatiques s’offrent à lui, avec notamment Que la fête commence en 1975 et Coup de Torchon en 1981 de Bertrand Tavernier, Les Galettes de Pont-Aven de Joël Séria en 1975 pour lequel il est nommé pour le César du Meilleur Acteur lors de la toute première Cérémonie, Quelques jours avec moi de Claude Sautet en 1988, Uranus de Claude Berri ou encore l’inoubliable Tous les matins du monde réalisé par Alain Corneau en 1991, un rôle magnifique qui lui vaudra l’année suivante une nouvelle nomination pour le César du Meilleur Acteur. -

Of Gods and Men

A Sony Pictures Classics Release Armada Films and Why Not Productions present OF GODS AND MEN A film by Xavier Beauvois Starring Lambert Wilson and Michael Lonsdale France's official selection for the 83rd Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film 2010 Official Selections: Toronto International Film Festival | Telluride Film Festival | New York Film Festival Nominee: 2010 European Film Award for Best Film Nominee: 2010 Carlo di Palma European Cinematographer, European Film Award Winner: Grand Prix; Ecumenical Jury Prize - 2010Cannes Film Festival Winner: Best Foreign Language Film, 2010 National Board of Review Winner: FIPRESCI Award for Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, 2011 Palm Springs International Film Festival www.ofgodsandmenmovie.com Release Date (NY/LA): 02/25/2011 | TRT: 120 min MPAA: Rated PG-13 | Language: French East Coast Publicist West Coast Publicist Distributor Sophie Gluck & Associates Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Sophie Gluck Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 124 West 79th St. Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10024 110 S. Fairfax Ave., Ste 310 550 Madison Avenue Phone (212) 595-2432 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] Phone (323) 634-7001 Phone (212) 833-8833 Fax (323) 634-7030 Fax (212) 833-8844 SYNOPSIS Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay… come what may. -

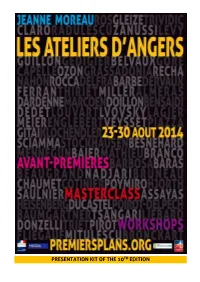

Presentation Kit of the 10Th Edition

n TH PRESENTATION KIT OF THE 10 EDITION PARTNERS Angers Workshops receive support from With the support of Angers Workshops would like to thank Université Angevine du Temps Libre Andégave communication Bouvet Ladubay Bureau d’Accueil des Tournages (Agence régionale) Centre de Ressources Audiovisuelles (Ville d’Angers) Cinéma Parlant Evolis Card Printer Forum des images Hexa Repro Hôtel Mercure Angers Centre Médiathèque de la Roseraie Mission AnCRE (Ville d’Angers) Morgan View Passeurs d’images Université catholique de l'Ouest (ISCEA) Angers Workshops | 10th edition | 23-30th August 2014 2 PRESENTATION OF THE 10TH EDITION 2013 residents with Olivier Ducastel, Claude-Éric Poiroux, 2012 residents with Raphaël Nadjari, Olivier Ducastel, Arnaud Gourmelen and Thibaut Bracq Claude-Éric Poiroux and Yves-Gérard Branger CREATED IN 2005, THE ANGERS WORKSHOPS are directed toward young European filmmakers with one or two short films to their credit and a first feature film in the works. During 5 days, they will be taught by recognized professionals from the world of cinema. This year, the focus will be on production, directing and actors. The residents are invited to come back in Angers in January 2015 during the 27th edition of the Festival. This new appointment will give them the opportunity to work on the development of their project. They will meet professionals about financial support and production. They also will have the opportunity to participate on the screenings and events of the Festival. The Workshops will offer them: . Screenings and analyses of film from the past and present. Training with established filmmakers and technicians who will bring to the classroom their professional experience and methods. -

Cinema Comparat/Ive Cinema

CINEMA COMPARAT/IVE CINEMA VOLUME III · no.7 · 2015 Editors: Gonzalo de Lucas (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) y Manuel Garin (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Associate Editors: Ana Aitana Fernández (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Núria Bou (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Xavier Pérez (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Assistant Editor: Chantal Poch Advisory Board: Dudley Andrew (Yale University, Estados Unidos), Jordi Balló (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, España), Raymond Bellour (Université Sorbonne-Paris III, Francia), Francisco Javier Benavente (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Nicole Brenez (Université Paris 1-Panthéon- Sorbonne, Francia), Maeve Connolly (Dun Laoghaire Institut of Art, Design and Technology, Irlanda), Thomas Elsaesser (University of Amsterdam, Países Bajos), Gino Frezza (Università de Salerno, Italia), Chris Fujiwara (Edinburgh International Film Festival, Reino Unido), Jane Gaines (Columbia University, Estados Unidos), Haden Guest (Harvard University, Estados Unidos), Tom Gunning (University of Chicago, Estados Unidos), John MacKay (Yale University, Estados Unidos), Adrian Martin (Monash University, Australia), Cezar Migliorin (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil), Alejandro Montiel (Universitat de València), Meaghan Morris (University of Sidney, Australia y Lignan University, Hong Kong), Raffaelle Pinto (Universitat de Barcelona), Ivan Pintor (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Àngel Quintana (Universitat de Girona, España), Joan Ramon Resina (Stanford University, Estados Unidos), Eduardo A.Russo (Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina), Glòria Salvadó -

Classic Auteur Theory

Part I Classic Auteur Theory COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 1 A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema François Truffaut Francois Truffaut began his career as a fi lm critic writing for Cahiers du Cinéma beginning in 1953. He went on to become one of the most celebrated and popular directors of the French New Wave, beginning with his fi rst feature fi lm, Les Quatre cents coup (The Four Hundred Blows, 1959). Other notable fi lms written and directed by Truffaut include Jules et Jim (1962), The Story of Adele H. (1975), and L’Argent de Poche (Small Change, 1976). He also acted in some of his own fi lms, including L’Enfant Sauvage (The Wild Child, 1970) and La Nuit Américain (Day for Night, 1973). He appeared as the scientist Lacombe in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Truffaut’s controversial essay, originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma in January 1954, helped launch the development of the magazine’s auteurist practice by rejecting the literary fi lms of the “Tradition of Quality” in favor of a cinéma des auteurs in which fi lmmakers like Jean Renoir and Jean Cocteau express a more personal vision. Truffaut claims to see no “peaceful co-existence between this ‘Tradition of Quality’ and an ‘auteur’s cinema.’ ” Although its tone is provocative, perhaps even sarcastic, the article served as a touchstone for Cahiers, giving the magazine’s various writers a collective identity as championing certain fi lmmakers and dismissing others. These notes have no other object than to attempt to These ten or twelve fi lms constitute what has been defi ne a certain tendency of the French cinema – a prettily named the “Tradition of Quality”; they force, by tendency called “psychological realism” – and to their ambitiousness, the admiration of the foreign press, sketch its limits. -

A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema Francois Truffaut

A CERTAIN TENDENCY OF THE FRENCH CINEMA FRANCOIS TRUFFAUT These notes have no other object than to attempt to define a certain tendency of the French cinema - a tendency called "psychological realism" - and to sketch its limits. If the French cinema exists by means of about a hundred films a year, it is well understood that only ten or twelve merit the attention of critics and cinephiles, the attention, therefore of "Cahiers." These ten or twelve films constitute what has been prettily named the "Tradition of Quality"; they force, by their ambitiousness, the admiration of the foreign press, defend the French flag twice a year at Cannes and at Venice where, since 1946, they regularly carry off medals, golden lions and grands prix. With the advent of "talkies," the French cinema was a frank plagiarism of the American cinema. Under the influence of Scarface, we made the amusing Pepe Le Moko. Then the French scenario is most clearly obliged to Prevert for its evolution: Quai Des Brumes (Port Of Shadows) remains the masterpiece of poetic realism. The war and the post-war period renewed our cinema. It evolved under the effect of an internal pressure and for poetic realism - about which one might say that it died closing Les Portes De La Nuit behind it - was substituted psychological realism, illustrated by Claude Autant-Lara, Jean Dellannoy, Rene Clement, Yves Allegret and Marcel Pagliero. SCENARISTS' FILMS If one is willing to remember that not so long ago Delannoy filmed Le Bossu and La Part De L'Ombre, Claude Autant-Lara Le Plombier Amoureux and Lettres D Amour, Yves Allegret La Boite Aux Reves and Les Demons De L’Aube, that all these films are justly recognized as strictly commercial enterprises, one will admit that, the successes or failures of these cineastes being a function of the scenarios they chose, La Symphonie Pastorale, Le Diable Au Corps (Devil In The Flesh), Jeux Interdits (Forbidden Games), Maneges, Un Homme Marche Dans La Ville, are essentially scenarists' films. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

Machines in the Garden

2 Machines in the Garden Jessica Riskin What does it mean to be alive and conscious: an aware, thinking creature? Using lifelike machines to discuss animation and consciousness is a major cultural preoc- cupation of the early twenty-first century; but few realize that this practice stretches back to the middle of the seventeenth century, and that actual lifelike machines, which peopled the landscape of late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, shaped this philosophical tradition from its inception. By the early 1630s, when René Des- cartes argued that animals and humans, apart from their capacity to reason, were automata, European towns and villages were positively humming with mechanical vitality, and mechanical images of living creatures had been ubiquitous for several centuries. Descartes and other seventeenth-century mechanists were therefore able to invoke a plethora of animal- and human-like machines. These machines fell into two main categories: the great many devices to be found in churches and cathedrals, and the automatic hydraulic amusements on the grounds of palaces and wealthy estates. Neither category of contraptions signified, in the first instance, what machine metaphors for living creatures later came to signify: passivity, rigidity, regularity, constraint, rote behavior, soullessness. Rather, the machines that informed the emergence of the Early Modern notion of the human-machine held a strikingly unfamiliar array of cultural and philosophical implications, notably the ten- dencies to act unexpectedly, playfully, willfully, surprisingly, and responsively. Moreover, neither the idea nor the ubiquitous images of human-machinery ran counter to Christian practice or doctrine. Quite the contrary: not only did automata appear first and most commonly in churches and cathedrals, the idea as well as the technology of human-machinery was indigenously Catholic.