Under Capricorn Symposium Were Each Given a 30 Minute Slot to Deliver Their Paper and Respond to Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At Home with the Movies

At Home with the Movies PAT COSTA THE BOBO (1967) Friday, May 26 (NBC) He plays a Russian-British Thursday, May 25 (CBS) double agent and Mia Farrow is The regular Friday night NBC the love interest, naturally. The As I A poorly-done comedy starring movie is. pre-empted this night best parts are taken by Tom Peter Sellers, this is about an ex- for Chronolog, the documentary Courtenay, Per Oscarsson and matador from Barcelona who de series that everyone says they Lionel Stander in supporting cides to become a singer and se watch when pollsters call to ask roles.- See It duce a high-class prostitute which programs are being played by Britt Ekland. viewed. It was rated A-3, unobjection able for adults, by the national Rossano Brazzi and Adolfo Catholic film office. Celi are lost in supproting roles. TOPAZ (1970) Those who watched the televi supporting awards for their The national Catholic film of Saturday, May 27 sion industry present itself a- work on "The Mary Tyler Moore fice rated this A-3, unobjection wards for 2'/s hours recently at A foreign-intrigue adventuite THE SINGING NUN (1966) Show", gave extended credit able "for adults. Monday, May 29 (NBC) the 24th annual Emmy show to the writers on that situation drama, this one uses the Cuban could have learned a lot about comedy, which is one of the best missile crisis as its launching A syrupy concoction starring this medium. written fun shows of ail time. Gabrielli pad, with John Forsyth the only Debbie Reynolds as a constantly jiame in the cast that hops from cheerful nun who manages a rec And probably the first lesson Lesson three could deal with Speaks in country to country in this politi ord contract in between serving was that TV knows no more another background job so cal cloak and dagger film. -

Jacques Prévert's Filmography

Jacques Prévert’s Filmo graphy Jacques Prévert has worked on more than a hundred of movies, yet his filmography remains underestimated. One counts about sixty films, short movies and full-length films, as well as about fifty written movies, in more or less accomplished stages: some are totally unpublished, the others had been written for directors having finally never shot them. Among the directed movies, some were so different from the initial scenario that Prévert refused to sign them. The non exhaustive filmography, which follows, presents only directed movies. The indicated year is that of the preceded French release, where necessary, that of the year of stake in production if there is more than a year of distance. Souvenir de Paris (1928), scriptwriter : Jacques Prévert, based on an idea of Pierre Prévert. Directors : Marcel Duhamel and Pierre Prévert. Baleydier (1931), author of the dialogues : Jacques Prévert, not credited. Scriptwriter : André Girard. Director : Jean Mamy. Ténérife (1932, short film, documentary), comment written by Jacques Prévert. Director : Yves Allégret. L’Affaire est dans le sac (1932, short film), scriptwriter, author of the adaptation and dialogues : Jacques Prévert. Director : Pierre Prévert. Bulles de savon (Seifenblasen, mute, Germany, 1933), comment of the French version written by Jacques Prévert. Scriptwriter and director : Slatan Dudow. Taxi de Minuit (1934, short film), based on the novel of Charles Radina. Scriptwriter, co-author of the adaptation (with Lilo Dammert) and author of the dialogues : Jacques Prévert. Director Albert Valentin. La Pêche à la baleine (1934, short film), interpretation by Jacques Prévert, based on his own text, written in 1933. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Welcome Home Mr Swanson Swedish Emigrants and Swedishness on Film Wallengren, Ann-Kristin; Merton, Charlotte

Welcome Home Mr Swanson Swedish Emigrants and Swedishness on Film Wallengren, Ann-Kristin; Merton, Charlotte 2014 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wallengren, A-K., & Merton, C., (TRANS.) (2014). Welcome Home Mr Swanson: Swedish Emigrants and Swedishness on Film. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 2 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 welcome home mr swanson Welcome Home Mr Swanson Swedish Emigrants and Swedishness on Film Ann-Kristin Wallengren Translated by Charlotte Merton nordic academic press Welcome Home Mr Swanson Swedish Emigrants and Swedishness on Film Ann-Kristin Wallengren Translated by Charlotte Merton nordic academic press This book presents the results of the research project ‘Film and the Swedish Welfare State’, funded by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation. -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

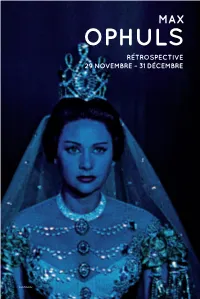

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

Snelling Wins Best of Staffing Client Award –

Snelling Snelling Corporate Office https://www.snelling.com Snelling Wins Best of Staffing Client Award - 2017 ...but that is not all Categories : EMPLOYER HOT TOPICS Date : February 16, 2017 Do you know what Katherine Hepburn, Jack Nicholson, Ingrid Bergman, Daniel Day Lewis, Walter Brennan, Meryl Streep and Snelling all have in common? Well, obviously the first 6 people listed are movie actors. However, they are not just actors. They are part of an elite group of actors. These 6 people are – in fact – the greatest Academy Award winners of all time. Hepburn leads the pack with 4 Oscar wins; Nicholson, Bergman, Day Lewis, Brennan and Streep have all won 3 times. But no matter how you cut it, all 6 are in a class of their own. But even as we prepare to watch the Academy Awards on Sunday, Feb. 26, to see if Casey Affleck beats Andrew Garfield or if Meryl Streep beats Emma Stone (and joins Ms. Hepburn in the 4x winner club), be aware that none of these actors have achieved what Snelling has. You see, actors have the Oscars; musicians have the Grammy’s; writers have the Pulitzer. Staffing firms have the Best of Staffing award – handed out to those elite staffing firms who have received “remarkable” reviews from the clients they serve. Best of Staffing Here at Snelling, we are honored to announce that we are (again) the winner of Inavero’s Best of 1 / 2 Snelling Snelling Corporate Office https://www.snelling.com Staffing® Client Awards for 2017. But the news gets better, for Snelling has achieved what none of the actors above have. -

Casablanca by Jay Carr the a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002

Casablanca By Jay Carr The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002 It’s still the same old story. Maybe more so. “Casablanca” was never a great film, never a profound film. It’s merely the most beloved movie of all time. In its fifty-year history, it has resisted the transmogrifica- tion of its rich, reverberant icons into camp. It’s not about the demimondaines washing through Rick’s Café Americain – at the edge of the world, at the edge of hope – in 1941. Ultimately, it’s not even about Bogey and Ingrid Bergman sacrificing love for nobility. It’s about the hold movies have on us. That’s what makes it so powerful, so enduring. It is film’s analogue to Noel Coward’s famous line about the amazing potency of cheap music. Like few films before or since, it sums up Hollywood’s genius for recasting archetypes in big, bold, universally accessible strokes, for turning myth into pop culture. Courtesy Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded It’s not deep, but it sinks roots into America’s Sound Division collective consciousness. As a love story, it’s flawed. We than a little let down by her genuflection to idealism. don’t feel a rush of uplift when trenchcoated Bogey, You feel passion is being subordinated to an abstraction. masking idealism with cynicism, lets Bergman, the love You want her to second-guess Rick and not go. of his life, fly off to Lisbon and wartime sanctuary with “Casablanca” leaves the heart feeling cheated. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care -

Newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 19/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 190 - September 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 19/06 (Nr. 190) September 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, sein, mit der man alle Fans, die bereits ein lich zum 22. Bond-Film wird es bestimmt liebe Filmfreunde! Vorgängermodell teuer erworben haben, wieder ein nettes Köfferchen geben. Dann Was gibt es Neues aus Deutschland, den ärgern wird. Schick verpackt in einem ed- möglicherweise ja schon in komplett hoch- USA und Japan in Sachen DVD? Der vor- len Aktenkoffer präsentiert man alle 20 auflösender Form. Zur Stunde steht für den liegende Newsletter verrät es Ihnen. Wie offiziellen Bond-Abenteuer als jeweils 2- am 13. November 2006 in den Handel ge- versprochen haben wir in der neuen Ausga- DVD-Set mit bild- und tonmäßig komplett langenden Aktenkoffer noch kein Preis be wieder alle drei Länder untergebracht. restaurierten Fassungen. In der entspre- fest. Wer sich einen solchen sichern möch- Mit dem Nachteil, dass wieder einmal für chenden Presseerklärung heisst es dazu: te, der sollte aber nicht zögern und sein Grafiken kaum Platz ist. Dieses Mal ”Zweieinhalb Jahre arbeitete das MGM- Exemplar am besten noch heute vorbestel- mussten wir sogar auf Cover-Abbildungen Team unter Leitung von Filmrestaurateur len. Und wer nur an einzelnen Titeln inter- in der BRD-Sparte verzichten. Der John Lowry und anderen Visionären von essiert ist, den wird es freuen, dass es die Newsletter mag dadurch vielleicht etwas DTS Digital Images, dem Marktführer der Bond-Filme nicht nur als Komplettpaket ”trocken” wirken, bietet aber trotzdem den digitalen Filmrestauration, an der komplet- geben wird, sondern auch gleichzeitig als von unseren Lesern geschätzten ten Bildrestauration und peppte zudem alle einzeln erhältliche 2-DVD-Sets. -

For Immediate Release December 2001 the MUSEUM of MODERN

MoMA | Press | Releases | 2001 | Mauritz Stiller Page 1 of 6 For Immediate Release December 2001 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PAYS TRIBUTE TO SWEDISH SILENT FILMMAKER MAURITZ STILLER Mauritz Stiller—Restored December 27, 2001–January 8, 2002 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2001–The Museum of Modern Art’s Film and Media Department is proud to present Mauritz Stiller—Restored from December 27, 2001 through January 8, 2002, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1. Most films in the exhibition are new prints, including five newly restored 35mm prints of Stiller’s films from the Swedish Film Institute. All screenings will feature simultaneous translation by Tana Ross and live piano accompaniment by Ben Model or Stuart Oderman. The exhibition was organized by Jytte Jensen, Associate Curator, Department of Film and Media, and Edith Kramer, Director, The Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, in collaboration with Jon Wengström, Curator, Cinemateket, the Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm. The period between 1911 and 1929 has been called the golden age of Swedish cinema, a time when Swedish films were seen worldwide, influencing cinematic language, inspiring directors in France, Russia, and the United States, and shaping audience expectations. Each new release by the two most prominent Swedish directors of the period—Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller—was a major event that advanced the art of cinema. "Unfortunately, Stiller is largely remembered as the man who launched Greta Garbo and as the Swede who didn’t make it in Hollywood," notes -

THE DARK PAGES the Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol

THE DARK PAGES The Newsletter for Film Noir Lovers Vol. 6, Number 1 SPECIAL SUPER-SIZED ISSUE!! January/February 2010 From Sheet to Celluloid: The Maltese Falcon by Karen Burroughs Hannsberry s I read The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett, I decide on who will be the “fall guy” for the murders of Thursby Aactually found myself flipping more than once to check and Archer. As in the book, the film depicts Gutman giving Spade the copyright, certain that the book couldn’t have preceded the an envelope containing 10 one-thousand dollar bills as a payment 1941 film, so closely did the screenplay follow the words I was for the black bird, and Spade hands it over to Brigid for safe reading. But, to be sure, the Hammett novel was written in 1930, keeping. But when Brigid heads for the kitchen to make coffee and the 1941 film was the third of three features based on the and Gutman suggests that she leave the cash-filled envelope, he book. (The first, released in 1931, starred Ricardo Cortez and announces that it now only contains $900. Spade immediately Bebe Daniels, and the second, the 1936 film, Satan Met a Lady, deduces that Gutman palmed one of the bills and threatens to was a light comedy with Warren William and Bette Davis.) “frisk” him until the fat man admits that Spade is correct. But For my money, and for most noirists, the 94 version is the a far different scene played out in the book where, when the definitive adaptation. missing bill is announced, Spade ushers Brigid The 1941 film starred Humphrey Bogart into the bathroom and orders her to strip naked as private detective Sam Spade, along with to prove her innocence. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress