Report on International Religious Freedom 2009: Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountstuart Elphinstone: an Anthropologist Before Anthropology

Mountstuart Elphinstone Mountstuart Elphinstone in South Asia: Pioneer of British Colonial Rule Shah Mahmoud Hanifi Print publication date: 2019 Print ISBN-13: 9780190914400 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2019 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190914400.001.0001 Mountstuart Elphinstone An Anthropologist Before Anthropology M. Jamil Hanifi DOI:10.1093/oso/9780190914400.003.0003 Abstract and Keywords During 1809, Mountstuart Elphinstone and his team of researchers visited the Persianate "Kingdom of Caubul" in Peshawar in order to sign a defense treaty with the ruler of the kingdom, Shah Shuja, and to collect information for use by the British colonial government of India. During his four-month stay in Peshawar, and subsequent two years research in Poona, India, Elphinstone collected a vast amount of ethnographic information from his Persian-speaking informants, as well as historical texts about the ethnology of Afghanistan. Some of this information provided the material for his 1815 (1819, 1839, 1842) encyclopaedic "An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul" (AKC), which became the ethnographic bible for Euro-American writings about Afghanistan. Elphinstone's competence in Farsi, his subscription to the ideology of Scottish Enlightenment, the collaborative methodology of his ethnographic research, and the integrity of the ethnographic texts in his AKC, qualify him as a pioneer anthropologist—a century prior to the birth of the discipline of anthropology in Europe. Virtually all Euro-American academic and political writings about Afghanistan during the last two-hundred years are informed and influenced by Elphinstone's AKC. This essay engages several aspects of the ethnological legacy of AKC. Keywords: Afghanistan, Collaborative Research, Ethnography, Ethnology, National Character For centuries the space marked ‘Afghanistan’ in academic, political, and popular discourse existed as a buffer between and in the periphery of the Persian and Persianate Moghol empires. -

Mysticism of Rahman Baba and Its Relevance to Our Education Hanif Ullah Khan

Mysticism of Rahman Baba and its Relevance to Our Education Hanif Ullah Khan Abstract Man is forgetful by nature. He is inclined towards injustice and ignorance and is in need of permanent guidance, that is, the Holy Qur’an and Sunnah of the Holy Prophet (S.A.W). The poetry of Rahman Baba is inspired by these sources (i.e. Quran and Sunnah of the Prophet) He invites man to study nature, which is lacking in our educational curriculum. He considers life in this world as an investment for the next world and is of the opinion that only that person who is capable of knowing his own self can use the opportunities of this world correctly. He invites man to go back to his inner self and know his spiritual entity / being. Keywords: Rahman Baba, Mysticism, God, Education, Introduction Islam has produced great scholars, philosophers and mystics, who were / are the custodians and promoters of the Islamic culture and its values in the world. The teachings of all these legends are capable of pulling our own and our succeeding generations from the inferiority complexes and put them on the path to God. Rahman Baba is one amongst them. I have studied this mystic poet of Pashto literature and can say that his poetry is an introduction to the fundamentals of human nature. He addresses man irrespective of his area of origin. He makes an irresistible appeal to all, irrespective of their caste, colour and creed. His ideas are ever fresh and new and are a guiding light for seekers of the truth. -

Guía Mundial De Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los

Guía Mundial de Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los inconquistables Pashtun! • 1-3 De un ciego que llevó a los Pashtunes Fuera de la Oscuridad • 5 Sobre todo Hospitalidad! • 8 Estilo de Resolución de Conflictos Pashtun • 23 Personas Mohmund: Poetas que alaban a Dios • 24 Estaría de acuerdo con los talibanes sobre esto! Queridos Amigos de oración, Yo soy un inglés, irlandés, y de descendencia sueca. Hace mil ochocientos años, mis antepasados irlandeses eran cazadores de cabezas que bebían la sangre de los cráneos de sus víctimas. Hace mil años mis antepasados vikingos eran guerreros que eran tan crueles cuando allanaban y destruían los pueblos desprotegidos, que hicieron la Edad Media mucho más oscura. Eventualmente la luz del evangelio hizo que muchos grupos de personas se convirtieran a Cristo, el único que es la Luz del Mundo. Su cultura ha cambiado, y comenzaron a vivir más por las enseñanzas de Jesús y menos por los caminos del mundo. La historia humana nos enseña que sin Cristo la humanidad puede ser increíblemente cruel con otros. Este mes vamos a estar orando por los Pashtunes. Puede parecer que estamos juzgando estas tribus afganas y pakistaníes. Pero debemos recordar que sin la obra transformadora del Espíritu Santo, no seríamos diferentes de lo que ellos son. Los Pashtunes tienen un código cultural de honor llamado Pashtunwali, lo que pone un cierto equilibrio de moderación en su conducta, pero también los estimula a mayores actos de violencia y venganza. Por esta razón, no sólo vamos a orar por tribus Pashtunes específicas, sino también por aspectos del código de honor Pashtunwali y otras dinámicas culturales que pueden mantener a los Pashtunes haciendo lo que Dios quiere que hagan. -

Pakhtun Identity Versus Militancy in Khyber

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2016(I-I).01 Pakhtun Identity versus Militancy in Vol. I, No. I (2016) | Page: 1 ‒ 23 p- ISSN: 2616-955X Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA: e-ISSN: 2663-7030 Exploring the Gap between Culture of L-ISSN: 2616-955X Peace and Militancy DOI: 10.31703/grr.2016(I-I).01 Hikmat Shah Afridi* Manzoor Khan Afridi† Syed Umair Jalal‡ Abstract The Pakhtun culture had been flourishing between 484 - 425 BC, in the era of Herodotus and Alexander the Great. Herodotus, the Greek historian, for the first time, used the word Pactyans, for people who were living in parts of Persian Satrapy, Arachosia between 1000 - 1 BC. The hymns’ collection from an ancient Indian Sanskrit Ved used the word Pakthas for a tribe, who were inhabitants of eastern parts of Afghanistan. Presently, the terms Afghan and Pakhtun were synonyms till the Durand Line divided Afghanistan and Pakhtuns living in Pakistan. For these people the code of conduct remained Pakhtunwali; it is the pre-Islamic way of life and honour code based upon peace and tranquillity. It presents an ethnic self-portrait which defines the Pakhtuns as an ethnic group having not only a distinct culture, history and language but also a behaviour. Key Words: Pakhtun, Militancy, Culture, Pakhtunwali, Identity Introduction Pakhtuns are trusted to act honourably, therefore Pakhtunwali qualifies as honour code “Doing Pashto” that signifies their deep love for the societal solidarity. Wrong doings are effectively checked through their inner voices, “Am I not a Pakhtun?” In addition, the cultural platforms have been used for highlighting social evils and creating harmony in the society. -

'Pashtunistan': the Challenge to Pakistan and Afghanistan

Area: Security & Defence - ARI 37/2008 Date: 2/4/2008 ‘Pashtunistan’: The Challenge to Pakistan and Afghanistan Selig S. Harrison * Theme: The increasing co-operation between Pashtun nationalist and Islamist forces against Punjabi domination could lead to the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan and the emergence of a new national entity: an ‘Islamic Pashtunistan’. Summary: The alarming growth of al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the Pashtun tribal region of north-western Pakistan and southern Afghanistan is usually attributed to the popularity of their messianic brand of Islam and to covert help from Pakistani intelligence agencies. But another, more ominous, reason also explains their success: their symbiotic relationship with a simmering Pashtun separatist movement that could lead to the unification of the estimated 41 million Pashtuns on both sides of the border, the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the emergence of a new national entity, an ‘Islamic Pashtunistan’. This ARI examines the Pashtun claim for an independent territory, the historical and political roots of the Pashtun identity, the implications for the NATO- or Pakistani-led military operations in the area, the increasing co-operation between Pashtun nationalist and Islamist forces against Punjabi domination and the reasons why the Pashtunistan movement, long dormant, is slowly coming to life. Analysis: The alarming growth of al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the Pashtun tribal region of north-western Pakistan and southern Afghanistan is usually attributed to the popularity of their messianic brand of Islam and to covert help from Pakistani intelligence agencies. But another, more ominous reason also explains their success: their symbiotic relationship with a simmering Pashtun separatist movement that could lead to the unification of the estimated 41 million Pashtuns on both sides of the border, the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the emergence of a new national entity, ‘Pashtunistan,’ under radical Islamist leadership. -

Taliban Militancy: Replacing a Culture of Peace

Taliban Militancy: Replacing a culture of Peace Taliban Militancy: Replacing a culture of Peace * Shaheen Buneri Abstract Time and again Pashtun leadership in Afghanistan and Pakistan has demanded for Pashtuns' unity, which however until now is just a dream. Violent incidents and terrorist attacks over the last one decade are the manifestation of an intolerant ideology. With the gradual radicalization and militarization of the society, festivals were washed out from practice and memory of the local communities were replaced with religious gatherings, training sessions and night vigils to instil a Jihadi spirit in the youth. Pashtun socio-cultural and political institutions and leadership is under continuous attack and voices of the people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA find little or no space in the mainstream Pakistani media. Hundreds of families are still displaced from their homes; women and children are suffering from acute psychological trauma. Introduction Pashtuns inhabit South Eastern Afghanistan and North Western Pakistan and make one of the largest tribal societies in the world. The Pashtun dominated region along the Pak-Afghan border is in the media limelight owing to terrorists’ activities and gross human rights violations. After the United States toppled Taliban regime in Afghanistan in 2001, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) became the prime destination for fleeing Taliban and Al-Qaeda fighters and got immense * Shaheen Buneri is a journalist with RFE/RL Mashaal Radio in Prague. Currently he is working on his book on music censorship in the Pashtun dominated areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan. 63 Tigah importance in the strategic debates around the world. -

Manchester Muslims: the Developing Role of Mosques, Imams and Committees with Particular Reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM

Durham E-Theses Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. AHMED, FIAZ How to cite: AHMED, FIAZ (2014) Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10724/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 DURHAM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. Fiaz Ahmed September 2013 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where dueacknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Mysticism of Rahman Baba and Its Educational Implications

MYSTICISM OF RAHMAN BABA AND ITS EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS Presented to: Department of Social Sciences Qurtuba University Peshawar (Pakistan) In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education ____________________ By Hanifullah Khan Ph.D Education, Research Scholar 2009 _____________________________________ Qurtuba University of Science and Information Technology Peshawar NWFP. (Pakistan) ii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL DOCTORAL DISSERTATION This is to certify that the Doctoral Dissertation of Mr. Hanifullah Khan Entitled Mysticism of Rahman Baba and Its Educational Implications Has been examined and approved for the requirement of Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Education (Supervisor and Dean of Social Sciences) Signature: ---------------------- Prof. Dr. Muhammad Saleem (Co – Supervisor) Signature: ---------------------- Prof. Dr. Parvez Mahjoor Examiners 1. Prof. Dr. Saeed Anwar Signature: --------------- Chairman, Education Department, Hazara University 2. Name: ---------------------------------- Signature:---------------- External Examiner, (Foreign Based) 3. Name: ---------------------------------- Signature:---------------- External Examiner, (Foreign Based) iii ABSTRACT Islam has produced great scholars, philosophers and mystics, who were / are the custodians and promoters of the Islamic culture and its values in the world. The teachings of all these legends are capable of pulling our own and our succeeding generations from the inferiority complexes and put them on the path to God. Rahman Baba is one amongst them and the reason for my selection of the Mysticism of Rahman Baba and Its Educational Implications for my Ph. D research study is that I have studied this mystic poet of Pashto literature and can say that his poetry is an introduction to the fundamentals of human nature. He addresses to man irrespective of his origin. He makes an irresistible appeal to all, irrespective of their caste, colour and creed. -

Gc University Lahore

Puritan Shift: Evolution of Ahl-i-Hadith Sect in the Punjab; A Discursive Study (1880-1947) Name: Amir Khan Shahid Session: 2008-2011 Roll No: 85-GCU-PhD-HIS-08 Department: History GC UNIVERSITY LAHORE i Puritan Shift: Evolution of Ahl-i-Hadith Sect in the Punjab; A Discursive Study (1880-1947) Submitted to GC University Lahore in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Ph D In History By Name Amir Khan Shahid Session: 2008-2011 Roll No: 85-GCU-PhD-His-08 Department: History GC UNIVERSITY LAHORE ii iii iv v vi DEDICATED To My Parents and teachers vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful, who enabled me to successfully complete this work. Then, first of all, I owe special gratitude to the honourable, Chairperson of History Department, Prof. Dr. Tahir Kamran, for his constant support and encouragement, both during the course work as well as the research work. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor respected Dr. Farhat Mahmud, who helped, encouraged and guided me throughout the process of research. I cannot forget his affectionate behavior during the whole course of my studies. I pay my warmest thanks to my ideal Prof. Dr. Irfan Waheed Usmani who devoted a lot of time in checking my work and giving necessary direction to address the queries suggested by Francis Robinson, Babra D. Metcalf, and Dietrich Reetz. He checked about three initial drafts of my thesis thoroughly and made it possible for final submission. Without the kind favour of Tahir Kamran and Irfan Waheed Usmani, I was unable to complete my research work. -

Bridging the Gaps

PRESENTS Peace Wisher’s TWIST OF FATES BRIDGING THE GAPS by NAZISH ZAFAR Associate Producer Express News Channel, Islamabad [email protected] Bridging the Gaps 1st edition: 2008 Published by Farishta Foundation International Title of book by Andreea Sarcani, Romania Price: Pak Rs.150 US $ 9.95 Collection of Critics’ Comments regarding ‘Twist of Fates’ Availability Khyberwatch (www.khyberwatch.com) Khyber.ORG (www.khyber.org) Tol Afghan (www.tolafghan.com/afzalshauq) Contacts Nazish Zafar Mobile: +92(0)332 5593635 Email: [email protected] Afzal Shauq Mobile: +92(0)346 5455414 Email: [email protected] Andreea Sarcani Mobile: +40(0)728 012092 Email: [email protected] DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the sweet daughter of Afzal Shauq Hadeel Breshna Afzal Khan, A life time chairperson of Farishta Foundation International with a hope that she will continue to keep her father’s sacred mission of love for peace, peace for humanity and humanity towards human’s life. Hadeel Breshna Afzal Khan a cute daughter of eastern papa and western mama More about Breshna • http://www.pukhtunwomen.org/node/195 • http://www.khyberwatch.com/gallery1/displayimage.php?album= 13&pos=1 AIMS & OBJECTIVES Farishta Foundation International aims at: • Making men share a sole identity as humans, discarding all divisions. • Promoting love for peace, peace for humanity and humanity towards prosperity of life. • Promoting art as an effective way of bridging the gaps between east and west. • Doing the best things in favour of ailing humanity. • Being global in thinking, with an attitude of will to share. • Drawing the face of humanity in best possible colours of words. -

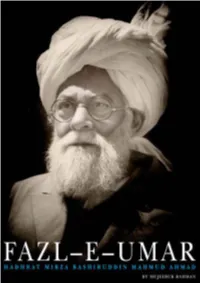

Fazl-E-Umar.Pdf

FAZL-E-UMAR The Life of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih II [ra] First published in the UK in 2012 by Islam International Publications Copyright © Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 2012 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For legal purposes the Copyright Acknowledgements constitute a continuation of this copyright page. ISBN: 978-0-85525-995-2 Designed and distributed by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK Author: Mujeebur Rahman Printed and bound by Polestar UK Print Limited CONTENTS Letter from Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad [atba] 1 Foreword 3 Comments by Sadr Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 9 PART 1 15 Early childhood and parental training 17 Education 41 Public speaking and writing 55 Childhood interests, games and pastimes 63 Circle of contacts 75 Belief in the truth of his father and its consequences 80 Ever–growing faith in the Promised Messiah [as] 88 The death and burial of the Promised Messiah [as] 90 Historic pledge of Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Mahmud Ahmad 98 PART 2 103 Establishment of Khilafat in the Ahmadiyya Movement 105 Efforts to support and strengthen the institution of Khilafat 110 PART 3 143 Khilafat of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad [ra] 144 Independence -

Translation of the Death List As Given by Late Afghan Minister of State Security Ghulam Faruq Yaqoubi to Lord Bethell in 1989

Translation of the death list as given by late Afghan Minister of State Security Ghulam Faruq Yaqoubi to Lord Bethell in 1989. The list concerns prisonners of 1357 and 1358 (1978-1979). For further details we refer to the copy of the original list as published on the website. Additional (handwritten) remarks in Dari on the list have not all been translated. Though the list was translated with greatest accuracy, translation errors might exist. No.Ch Name Fathers Name Profession Place Accused Of 1 Gholam Mohammad Abdul Ghafur 2nd Luitenant Of Police Karabagh Neg. Propaganda 2 Shirullah Sultan Mohammad Student Engineering Nerkh-Maidan Enemy Of Rev. 3 Sayed Mohammad Isa Sayed Mohammad Anwar Mullah Baghlan Khomeini 4 Sefatullah Abdul Halim Student Islam Wardak Ikhwani 5 Shujaudin Burhanudin Pupil 11th Grade Panjsher Shola 6 Mohammad Akbar Mohabat Khan Luitenant-Colonel Kohestan Ikhwani 7 Rahmatullah Qurban Shah Police Captain Khanabad Ikhwani 8 Mohammad Azam Mohammad Akram Head Of Archive Dpt Justice Nejrab Ikhwani 9 Assadullah Faludin Unemployed From Iran Khomeini 10 Sayed Ali Reza Sayed Ali Asghar Head Of Income Dpt Of Trade Chardehi Khomeini 11 Jamaludin Amanudin Landowner Badakhshan Ikhwani 12 Khan Wasir Kalan Wasir Civil Servant Teachers Education Panjsher Khomeini 13 Gholam Reza Qurban Ali Head Of Allhjar Transport. Jamal-Mina Khomeini 14 Sayed Allah Mohammad Ajan Civil Servant Carthographical Off. Sorubi Anti-Revolution 15 Abdul Karim Haji Qurban Merchant Farjab Ikhwani 16 Mohammad Qassem Nt.1 Mohammad Salem Teacher Logar Antirevol.