Gc University Lahore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religie W Azji Południowej

RAPORT OPRACOWANY W RAMACH PROJEKTU ROZBUDOWA BIBLIOTEKI WYDZIAŁU INFORMACJI O KRAJACH POCHODZENIA WSPÓŁFINANSOWANEGO PRZEZ EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW GRUDZIEŃ 2010 (ODDANY DO DRUKU W KWIETNIU 2011) RELIGIE W AZJI POŁUDNIOWEJ Sylwia Gil WYDZIAŁ INFORMACJI O KRAJACH POCHODZENIA UDSC EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW RAPORT OPRACOWANY W RAMACH PROJEKTU ROZBUDOWA BIBLIOTEKI WYDZIAŁU INFORMACJI O KRAJACH POCHODZENIA WSPÓŁFINANSOWANEGO PRZEZ EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW RELIGIE W AZJI POŁUDNIOWEJ Sylwia Gil GRUDZIEŃ 2010 (ODDANY DO DRUKU W KWIETNIU 2011) EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW Sylwia Gil – Religie w Azji Południowej grudzień 2010 (oddano do druku w kwietniu 2011) – WIKP UdSC Zastrzeżenie Niniejszy raport tematyczny jest dokumentem jawnym, a opracowany został w ramach projektu „Rozbudowa Biblioteki Wydziału Informacji o Krajach Pochodzenia”, współfinansowanego ze środków Europejskiego Funduszu na rzecz Uchodźców. W ramach wspomnianego projektu, WIKP UdSC zamawia u ekspertów zewnętrznych opracowania, które stanowią pogłębioną analizę wybranych problemów/zagadnień, pojawiających się w procedurach uchodźczych/azylowych. Informacje znajdujące się w ww. raportach tematycznych pochodzą w większości z publicznie dostępnych źródeł, takich jak: opracowania organizacji międzynarodowych, rządowych i pozarządowych, artykuły prasowe i/lub materiały internetowe. Czasem oparte są także na własnych spostrzeżeniach, doświadczeniach i badaniach terenowych ich autorów. Wszystkie informacje zawarte w niniejszym raporcie zostały -

Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe

Hasan Deniz · Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe [email protected] Hasan Deniz • Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe 123 [email protected] Editors Hasan Deniz Lisa A. Borgerding College of Education College of Education, Health, University of Nevada Las Vegas and Human Services Las Vegas, NV Kent State University USA Kent, OH USA ISBN 978-3-319-90938-7 ISBN 978-3-319-90939-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90939-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018940410 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Historical Places of Pakistan Minar-E-Pakistan

Historical places of Pakistan Minar-e-Pakistan: • Minar-e-Pakistan (or Yadgaar-e-Pakistan ) is a tall minaret in Iqbal Park Lahore, built in commemoration of the Lahore Resolution. • The minaret reflects a blend of Mughal and modern architecture, and is constructed on the site where on March 23, 1940, seven years before the formation of Pakistan, the Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution (Qarardad-e-Lahore ), demanding the creation of Pakistan. • The large public space around the monument is commonly used for political and public meetings, whereas Iqbal Park area is ever so popular among kite- flyers. • The tower rises about 60 meters on the base, thus the total height of minaret is about 62 meters above the ground. • The unfolding petals of the flower-like base are 9 meters high. The diameter of the tower is about 97.5 meters (320 feet). Badshahi Mosque: or the 'Emperor's Mosque', was ,( د ه :The Badshahi Mosque (Urdu • built in 1673 by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in Lahore, Pakistan. • It is one of the city's best known landmarks, and a major tourist attraction epitomising the beauty and grandeur of the Mughal era. • Capable of accommodating over 55,000 worshipers. • It is the second largest mosque in Pakistan, after the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. • The architecture and design of the Badshahi Masjid is closely related to the Jama Masjid in Delhi, India, which was built in 1648 by Aurangzeb's father and predecessor, Emperor Shah Jahan. • The Imam-e-Kaaba (Sheikh Abdur-Rahman Al-Sudais of Saudi Arabia) has also led prayers in this mosque in 2007. -

Conservation of Historic Monuments in Lahore: Lessons from Successes and Failures

Pak. J. Engg. & Appl. Sci. Vol. 8, Jan., 2011 (p. 61-69) Conservation of Historic Monuments in Lahore: Lessons from Successes and Failures 1 Abdul Rehman 1 Department of Architecture, University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore Abstract A number of conservation projects including World Heritage sites are underway in Lahore Pakistan. The most important concern for conservation of these monuments is to maintain authenticity in all aspects. Although we conserve, preserve and restore monuments we often neglect the aspects of authenticity from different angles. The paper will focus on three case studies built around 1640’s namely Shalamar garden, Shish Mahal and Jahangir’s tomb. The first two sites are included in the World Heritage List while the third one is a national monument and has a potential of being included in the world heritage list. Each one of these monument has a special quality of design and decorative finishes and its own peculiar conservation problems which need innovative solutions. The proposed paper will briefly discuss the history of architecture of these monuments, their conservation problems, and techniques adopted to revive them to the original glory. To what degree the government is successful in undertaking authentic conservation and restoration is examined. The paper draws conclusions with respect to successes and failures in these projects and sees to what degree the objectives of authenticity have been achieved. Key Words: Authenticity, World Heritage sites, Mughal period monuments, conservation in Lahore, role International agencies 1. Introduction 2. Authenticity and Conservation Lahore, cultural capital of Pakistan, is one of the Authentic conservation needs research most important centers of architecture (Figure 1) documentation and commitment for excellence. -

Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Qadiani

1 2 Who Are Qadyane’s? Most Of The Articles Are Written By Maulana Yousuf Ludyanvi Rahmatullah Alaihi Contents: - 1) What does Quran Say About the Finality of Prophet Hood(S.A.W). 2) Finality of Prophet(S.A.W) in the light of Ahadiht’s. 3) What is Qadyanism. 4) Ahmedi or Qadyani. 5) Qadyani Debase the Islamic Kalimah. 6) Difference Between Qadyani and Muslims. 7) Character of Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Qadyani. 8) Could He be a Prophet. 9) Message to Muslim Ummah. 10) Identification of Promised Messiah. 11) Identification of Imam Mahdi. 12) Final Rejoinder of Mirza Tahir. 13) Dr. Abdul Salam and His Nobel Prize. 14) The Qadyani Funeral. 15) Reply to Mirza Tahir Challenge 16) Two Interesting Mubahalas. 17) Verdicts on Qadyanis. 18) Maloon Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Qadyani in the mirror of his own Writings. 3 WHAT DOES THE HOLY QURAN SAY ABOUT FINALITY OF PROPHETHOOD The holy Quran and the holy Prophet's Ahadith (Traditions) eloquently prove that prophethood ('nubuwwat' and 'risalat') came to an end with our Prophet Muhammad (SAW). There are decisive verses to that effect. Being the last Prophet in the chain of prophethood no one ever shall now succeed him to that status or dignity "Muhammad is not the father of any man among you, but he is the Messenger of Allah and the Seal of the Prophets; and Allah (SWT) is Aware of all things." (Quran. AI-Ahzab 33:40). INTERPRETATION OF THE HOLY QURAN All the interpreters of the Holy Quran agree on the meaning of 'Khatam-un-Nabieen' that our Prophet (SAW) was the last of all the prophets and none shall he exalted to the lofty position of prophethood after him. -

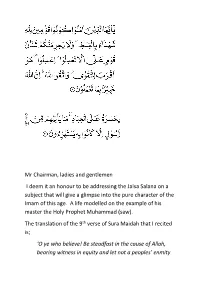

Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen I Deem It an Honour to Be Addressing the Jalsa Salana on a Subject That Will Give a Glimpse In

Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen I deem it an honour to be addressing the Jalsa Salana on a subject that will give a glimpse into the pure character of the Imam of this age. A life modelled on the example of his master the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw). The translation of the 9th verse of Sura Maidah that I recited is; ‘O ye who believe! Be steadfast in the cause of Allah, bearing witness in equity and let not a peoples’ enmity incite you to act otherwise than with justice. Be always just, that is nearer to righteousness. And fear Allah. Surely Allah is well aware of what you do.’ The other is from sura Yasin verse 31; ‘Alas for My servants! There comes not a Messenger but they mock at him’. History bears witness that this indeed forms part of the life of every Messenger of God The Holy Prophet (saw), was known as Al Ameen by the Meccans but as soon as he made his claim, he was met with ridicule and persecution from those very same people. The Promised Messiah (as) , prior to his claim was championed as the saviour of Islam, but no sooner under Divine command had he made his claim that he too faced bitter opposition. He always displayed patience, sympathy and kindness to those who opposed him, this is the subject I must speak on today. Today we live in a world filled with hate, violence and rancour. The incidents of the Promised Messiah (as) kindness even to his opponents are a lesson for humanity. -

Mughal Kings and Kingdoms From

Mughal Kings and Kingdoms from http://www.oxfordartonline.com Dynasty of Central Asian origin that ruled portions of the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1857. The patronage of the Mughal emperors had a significant impact on the development of architecture, painting and a variety of other arts. The Mughal dynasty was founded by Babur (reg 1526–30), a prince descended from Timur and Chingiz Khan. Having lost his Central Asian kingdom of Ferghana, Babur conquered Kabul and then in 1526 Delhi (see Delhi, §I). He was a collector of books and his interests in art are apparent in his memoirs, the Bāburnāma, written in Chagatay Turkish. Babur built palace pavilions and laid out gardens. The latter, divided into four parts by water courses (Ind.-Pers. chār-bāgh, a four-plot garden), became a model for subsequent Mughal gardens. Babur was succeeded by Humayun (reg 1530–40, 1555–6), who initiated a number of building projects, most notably the Purana Qila‛ in Delhi. Sher Shah usurped the throne and drove Humayun into exile in 1540. During the Sur (ii) interregnum, Humayun travelled to Iran where he was able to attract a number of Safavid court artists to his service. In 1545 he re-established Mughal power in the subcontinent with the capture of Kabul, which was the centre of Humayun’s court until he took Delhi in 1555. Little is known of the Kabul period, but painters from Iran arrived there, and apparently some manuscripts were produced. Humayun died in 1556, shortly after his return to Delhi. Akbar (reg 1556–1605) inherited a small and precarious kingdom, but by the time of his death in 1605 it had been transformed into a vast empire stretching from Kabul to the Deccan. -

The Light Islam As: and the PEACEFUL Lahore TOLERANT Ahmadiyya & Islamic Review RATIONAL Movement INSPIRING for Over Seventy- • Five Years July – August 2001 •

“Call to the path of thy Lord with wisdom and goodly exhortation, and argue with people in the best manner.” (The Holy Quran 16:125) • • Exponent Presents of Islam The Light Islam as: and the PEACEFUL Lahore TOLERANT Ahmadiyya & Islamic Review RATIONAL Movement INSPIRING for over seventy- • five years July – August 2001 • Published on the World-Wide Web at: http://www.muslim.org Speeches at the Ahmadiyya Islamic Convention, Columbus, Ohio, August 2001 Vol. 78 CONTENTS No. 4 Human behavior in Islam by Dr. K. Ghafoerkhan, Suriname. ........................................ 3 Why I am a Muslim by Ibrahim Mohammad, South Africa. .................................. 5 Translation of Mujaddid-e Azam by Akram Ahmad, U.S.A. ..................................................... 8 The onward march of Ahmadiyya teachings by Reza Ghafoerkhan, Holland/Suriname. .......................... 11 íëûáü´Ë·åã çêô©ã¤ Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore Inc., U.S.A. 1315 Kingsgate Road, Columbus, Ohio, 43221– 1504, U.S.A. 2 THE LIGHT JULY – AUGUST 2001 The Light was founded in 1921 as the organ of the AHMADIYYA About ourselves ANJUMAN ISHA‘AT ISLAM (Ahmadiyya Association for the propaga- tion of Islam) of Lahore, Pakistan. The Islamic Review was published Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore in England from 1913 for over 50 years, and in the U.S.A. from 1980 has branches in the following countries: to 1991. The present periodical represents the beliefs of the world- U.S.A. Australia wide branches of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam, Lahore. U.K. Canada Holland Fiji ISSN: 1060–4596 Indonesia Germany Editor: Dr. Zahid Aziz. Format and Design: The Editor. -

History of Conservation of Shish Mahal in Lahore-Pakistan

Int'l Journal of Research in Chemical, Metallurgical and Civil Engg. (IJRCMCE) Vol. 3, Issue 1 (2016) ISSN 2349-1442 EISSN 2349-1450 History of Conservation of Shish Mahal in Lahore-Pakistan M. Kamran1, M.Y. Awan, and S. Gulzar The most beautiful of them are Shish Mahal (Mirror Palace), Abstract— Lahore Fort is situated in north-west side of Lahore Naulakha Pavilion, Diwan-e-Aam, Diwan-e-Khas, Jehangir’s city. Lahore fort is an icon for national identity and symbol of Quadrants, Moti Masjid, Masti and Alamgiri Gates etc [2]. both historical and legendry versions of the past. It preserves all Shish Mahal is the most prominent, beautiful and precious styles of Mughal architecture. The fort has more than 20 large and small monuments, most of them are towards northern side. palace in Lahore Fort. It is situated in north-west side in the Shish Mahal is one of them and was built in 1631-1632 by Mughal Fort. It is also known as palace of mirrors because of extensive Emperor Shah Jahan. Shish Mahal being most beautiful royal use of mirror work over its walls and ceilings. It was formed as residence is also known as palace of mirrors. Shish Mahal has a harem (private) portion of the Fort. The hall was reserved for faced serious problems throughout the ages. Temperature personal use by the imperial family [3]. Shish Mahal was listed changes, heavy rains, lightning and termite effect were the as a protected monument under the Antiquities Act by serious causes of decays for Shish Mahal. -

With Love to Muhammad (Sa) the Khatam-Un-Nabiyyin

With Love to Muhammadsa the Khātam-un-Nabiyyīn The Ahmadiyya Muslim Understanding of Finality of Prophethood Farhan Iqbal | Imtiaz Ahmed Sra With Love to Muhammadsa the Khātam-un-Nabiyyīn Farhan Iqbal & Imtiaz Ahmed Sra With Love to Muhammadsa the Khātam-un-Nabiyyīn by: Farhan Iqbal and Imtiaz Ahmed Sra (Missionaries of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamā‘at) First Published in Canada: 2014 © Islam International Publications Ltd. Published by: Islam International Publications Ltd. Islamabad, Sheephatch Lane Tilford, Surrey GU10 2AQ United Kingdom For further information, you may visit www.alislam.org Cover Page Design: Farhan Naseer ISBN: 978-0-9937731-0-5 This book is dedicated to the 86 Ahmadī Muslims who were martyred on May 28, 2010, in two mosques of Lahore, Pakistan, as well as all the other martyrs of Islām Ahmadiyya, starting from Hazrat Maulvī ‘Abdur Rahmān Shahīdra and Hazrat Sāhibzāda Syed ‘Abdul Latīf Shahīdra, to the martyrs of today. َو ُﻗ ْﻞ َﺟﺎٓ َء اﻟْ َﺤ ُّـﻖ َو َز َﻫ َﻖ اﻟْ َﺒ ِﺎﻃ ُؕﻞ ِا َّن اﻟْ َﺒ ِﺎﻃ َﻞ َﰷ َن َز ُﻫ ْﻮﻗًﺎ And proclaim: ‘Truth has come and falsehood has vanished away. Verily, falsehood is bound to vanish.’ —Sūrah Banī Isrā’īl, 17:82 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... i Publishers’ Note ...................................................................................................... iii Preface ........................................................................................................................ v Foreword................................................................................................................ -

Manchester Muslims: the Developing Role of Mosques, Imams and Committees with Particular Reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM

Durham E-Theses Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. AHMED, FIAZ How to cite: AHMED, FIAZ (2014) Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10724/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 DURHAM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. Fiaz Ahmed September 2013 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where dueacknowledgement has been made in the text. -

The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam

THE RECONSTRUCTION OF RELIGIOUS THOUGHT IN ISLAM MUHAMMAD IQBAL IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN All Rights Reserved Publisher Prof. Dr. Baseera Ambreen Director Iqbal Academy Pakistan Government of Pakistan National Heritage & Culture Division 6th Floor, Aiwan-i-Iqbal, Edgerton Road, Lahore. Tel: 92-42-36314510, 99203573, Fax: 92-42-36314496 Email. [email protected] Website: www.allamaiqbal.com ISBN: 978-969-416-552-3 1st Edition : 1986 2nd Edition : 1989 3rd Edition : 2015 4th Edition : 2018 5th Edition : 2021 Quantity : 500 Price : Rs. 540 Printed at : Fareedia Art Press International, Lahore _________ Sales Office:116-McLeod Road, Lahore. Ph.37357214 THE RECONSTRUCTION OF RELIGIOUS THOUGHT IN ISLAM iii iv C ONTENTS EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION vii-xx PREFACE xxi-xxii I. KNOWLEDGE AND RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE 1-22 II. THE PHILOSOPHICAL TEST OF THE REVELATIONS OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE 23-49 III. THE CONCEPTION OF GOD AND THE MEANING OF PRAYER 50-75 IV. THE HUMAN EGO–HIS FREEDOM AND IMMORTALITY 76-98 V. THE SPIRIT OF MUSLIM CULTURE 99-115 VI. THE PRINCIPLE OF MOVEMENT IN THE STRUCTURE OF ISLAM 116-142 VII. IS RELIGION POSSIBLE? 143-157 NOTES AND REFERENCES 158-223 BIBLIOGRAPHY 225-245 QUR’ANIC INDEX 246-251 INDEX 252-285 v vi EDITOR‟S INTRODUCTION In the present edition of Allama Iqbal‟s Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, an attempt has been made at providing references to many authors cited in it and, more particularly, to the passages quoted from their works. The titles of these works have not always been given by the Allama and, in a few cases, even the names of the authors have to be worked out from some such general descriptions about them as „the great mystic poet of Islam‟, „a modern historian of civilization‟, and the like.