Utrecht University from Let's Play to Let's Eat How Youtube's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of Youtube

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of YouTube Andra Teodora Pacuraru Student Number: 11693436 30/08/2018 Supervisor: Alberto Cossu Second Reader: Bernhard Rieder MA New Media and Digital Culture University of Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 4 Neoliberalism & Personal Branding ............................................................................................ 4 Mass Self-Communication & Identity ......................................................................................... 8 YouTube & Micro-Celebrities .................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 2: Case Studies ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 21 Who They Are ........................................................................................................................... 21 Video Evolution ......................................................................................................................... 22 Audience Statistics ................................................................................................................... -

Religious Ownership/Use

PT 04-1 Tax Type: Property Tax Issue: Religious Ownership/Use STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS 3 ANGELS BROADCASTING NETWORK A.H. Docket # 01-PT-0027 P. I. # 174-116-11 v. Docket # 00-28-01 Docket # 01-28-07 THE DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS Barbara S. Rowe Administrative Law Judge RECOMMENDATION FOR DISPOSITION Appearances: Mr. Kent R. Steinkamp, Special Assistant Attorney General for the Illinois Department of Revenue; Mr. Nicholas P. Miller, Sidley, Austin, Brown, Wood, L.L.C., Mr. Lee Boothby, Boothby and Yingst, and Mr. D. Michael Riva for 3 Angels Broadcasting Network; Ms. Merry Rhodes and Ms. Joanne H. Petty, Robbins, Schwartz, Nicholas, Lifton and Taylor, Ltd. for Thompsonville Community High School District 112. Synopsis: The hearing in this matter was held to determine whether Franklin County Parcel Index No. 174-116-11 qualified for exemption during the 2000 and/or 2001 assessment years. Danny Shelton, president of Three Angels Broadcasting, (hereinafter referred to as the "Applicant" or “3ABN”); Larry Ewing, director of finance in 2002 of applicant; Alan Lovejoy, CPA and accountant; Walter Thompson, chairman of the board in 2002 of applicant; Bill Bishop, minister in the Seventh-day Adventist Church and member of the pastoral staff of applicant; Kenneth Denslow, president of the Illinois Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church; Mollie Steenson, department coordinator of applicant; and Linda Shelton, vice president of applicant, were present and testified on behalf of applicant. Cynthia Humm, Supervisor of Assessments of Franklin County was present and testified on behalf of Thompsonville Community High School District No. -

Youtube Comments As Media Heritage

YouTube comments as media heritage Acquisition, preservation and use cases for YouTube comments as media heritage records at The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision Archival studies (UvA) internship report by Jack O’Carroll YOUTUBE COMMENTS AS MEDIA HERITAGE Contents Introduction 4 Overview 4 Research question 4 Methods 4 Approach 5 Scope 5 Significance of this project 6 Chapter 1: Background 7 The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision 7 Web video collection at Sound and Vision 8 YouTube 9 YouTube comments 9 Comments as archival records 10 Chapter 2: Comments as audience reception 12 Audience reception theory 12 Literature review: Audience reception and social media 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter 3: Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 16 YouTube’s Data API 16 Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 17 YouTube API quotas 17 Calculating quota for full web video collection 18 Updating comments collection 19 Distributed archiving with YouTube API case study 19 Collecting 1.4 billion YouTube annotations 19 Conclusions 20 Chapter 4: YouTube comments within FRBR-style Sound and Vision information model 21 FRBR at Sound and Vision 21 YouTube comments 25 YouTube comments as derivative and aggregate works 25 Alternative approaches 26 Option 1: Collect comments and treat them as analogue for the time being 26 Option 2: CLARIAH Media Suite 27 Option 3: Host using an open third party 28 Chapter 5: Discussion 29 Conclusions summary 29 Discussion: Issue of use cases 29 Possible use cases 30 Audience reception use case 30 2 YOUTUBE -

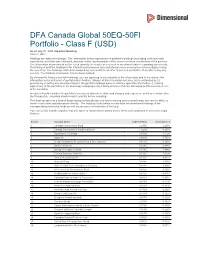

DFA Canada Global 50EQ-50FI Portfolio - Class F (USD) As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: RBC Holdings Are Subject to Change

DFA Canada Global 50EQ-50FI Portfolio - Class F (USD) As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: RBC Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. This fund operates as a fund-of-funds and generally allocates its assets among other mutual funds, but has the ability to invest in securities and derivatives directly. The holdings listed below contain both the investment holdings of the corresponding underlying funds as well as any direct investments of the fund. -

Private Broadcasting and the Path to Radio Broadcasting Policy in Canada

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 13–20 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v6i1.1219 Article Private Broadcasting and the Path to Radio Broadcasting Policy in Canada Anne Frances MacLennan Department of Communication Studies, York University, Toronto, M3J 1P3, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 6 October 2017 | Accepted: 6 December 2017 | Published: 9 February 2018 Abstract The largely unregulated early years of Canadian radio were vital to development of broadcasting policy. The Report of the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting in 1929 and American broadcasting both changed the direction of Canadian broadcasting, but were mitigated by the early, largely unregulated years. Broadcasters operated initially as small, indepen- dent, and local broadcasters, then, national networks developed in stages during the 1920s and 1930s. The late adoption of radio broadcasting policy to build a national network in Canada allowed other practices to take root in the wake of other examples, in particular, American commercial broadcasting. By 1929 when the Aird Report recommended a national net- work, the potential impact of the report was shaped by the path of early broadcasting and the shifts forced on Canada by American broadcasting and policy. Eventually Canada forged its own course that pulled in both directions, permitting both private commercial networks and public national networks. Keywords America; broadcasting; Canada; commission; frequencies; media history; national; networks; radio; religious Issue This article is part of the issue “Media History and Democracy”, edited by David W. Park (Lake Forest College, USA). © 2018 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

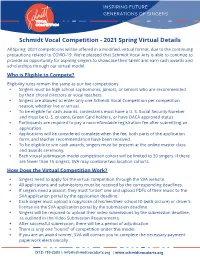

Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details

INSPIRING FUTURE GENERATIONS OF SINGERS VOCAL COMPETITION Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details All Spring 2021 competitions will be offered in a modified, virtual format, due to the continuing precautions related to COVID-19. We’re pleased that Schmidt Vocal Arts is able to continue to provide an opportunity for aspiring singers to showcase their talent and earn cash awards and scholarships through our virtual model. Who is Eligible to Compete? Eligibility rules remain the same as our live competitions: • Singers must be high school sophomores, juniors, or seniors who are recommended by their choral directors or vocal teachers. • Singers are allowed to enter only one Schmidt Vocal Competition per competition season, whether live or virtual. • To be eligible for cash awards, contestants must have a U. S. Social Security Number and must be U. S. citizens, Green Card holders, or have DACA approved status. • Participants are required to pay a non-refundable registration fee after submitting an application. • Applications will be considered complete when the fee, both parts of the application form, and teacher recommendation have been received. • To be eligible to win cash awards, singers must be present at the online master class and awards ceremony. • Each virtual submission model competition cohort will be limited to 30 singers. If there are fewer than 15 singers, SVA may combine two location cohorts. How Does the Virtual Competition Work? • Singers need to apply for the virtual competition through the SVA website. • All applications and submissions must be received by the corresponding deadlines. • If singers need a pianist, they must “order” one and upload PDFs of their music to the SVA application portal by the application deadline. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

Invocation Time to Tune in the Phenomenon of African American Religious Broadcasting

Invocation Time to Tune In The Phenomenon of African American Religious Broadcasting Shine on me, shine on me. Let the light from the lighthouse Shine on me. — “Shine on Me,” in African American Heritage Hymnal At the dawn of the twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois described the black preacher as “the most unique personality developed by the Negro on American soil.”1 For the majority of the century, because of societal constraints regulating the movement of persons of color in America, these spiritual poets were largely confned to preaching to their own racial and residential communities. Today, however, with the victo- ries of the civil rights era and the emergence of advanced forms of media communication, many of these dynamic personalities have gained wider visibility both nationally and internationally. To channel-surf from BET to TBN to MBC to the Word Network is to witness the creative genius and artistic imaginations of these religious fgures. And it would be vir- tually impossible to enter any African American Christian congregation and fnd someone who had not heard of such televangelists as Bishop T. D. Jakes, Bishop Eddie Long, and Pastor Crefo Dollar. These preach- ers seem to have become ubiquitous in black popular culture as a result of their constant television broadcasts, mass video distributions, printed publications, gospel stage plays, musical recordings, and gargantuan congregations. With an astute marketing consciousness, these preachers and their style of ministry have found an enduring place in the African American religious imagination. 1 2 Invocation Televangelism and the Black Church in America Any discussion of televangelism and the black church involves an engage- ment with two distinct areas of religious expression that have grown exponentially in the post−civil rights era: religious broadcasting and the megachurch movement. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

Youtube API V3 Rule Set Documentation

YouTube API v3 Rule Set Documentation Table Of Contents YouTube API v3 ...................................................................................................................................1 Scope ..............................................................................................................................................1 Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................................2 Overview ........................................................................................................................................2 Prerequisites ...................................................................................................................................2 Installation ......................................................................................................................................2 Import Error Templates ...............................................................................................................2 Import the Rule Set .....................................................................................................................2 Configuration ..................................................................................................................................3 Extract Meta Data ...........................................................................................................................3 Get Title/Description ...................................................................................................................3