Oil & Gas E-Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroleum News Bakken 121513 Petroleum News 082904

page Statoil hits 14th top IP well 8 in 22 weeks Vol. 2, No. 35 • www.PetroleumNewsBakken.com A weekly newspaper for industry and government Week of December 15, 2013 • $2.50 l NATURAL GAS Producing amid the windrows Finishing touches NDPC flaring task force to submit recommendations to NDIC in January By MAXINE HERR “The nature of this business is that VERN WHITTEN PHOTOGRAPHY For Petroleum News Bakken drillers drill, operators operate, and they he North Dakota Petroleum Council, NDPC, sign a long-term contract with a gas Tflaring task force is putting finishing touch- processing company and they walk es on its recommendations to reduce flaring in the away.” —Department of Mineral Resources Director state. Lynn Helms In September, Gov. Jack Dalrymple requested the development of a task force to study the prob- Wells pumping on a Hess Corporation pad in the Traux field subcommittee has some recommendations that southeast of Williston in southern Williams County, N.D. lem and provide some solid solutions to the North needed further review. Dakota Industrial Commission. The task force “We want to give it a good review and make will present its findings at the Jan. 29 commission sure membership and everyone’s ready,” Dille ND operators increasing well meeting. said. “We want to get it as good as we can. As far Task force Chairman Eric Dille of EOG densities to even higher levels as recommendations on flaring, goals, and crite- Resources told Petroleum News Bakken that the ria, we have developed some targets we think we North Dakota operators continue to increase well densi- task force had hoped to present at the Dec. -

Archrock, Inc. AROC (DB) Baker Hughes BHGE

Abraxas Petr. AXAS (RM) Helix Energy HLX (MWM) Sanchez Engy SN (RM) Anadarko APC (CM) Helmerich/Payne HP (DB) Sanchez Mid. SNMP (GV) Apache APA (CM) Hi-Crush Partners HCLP (MWM) Schlumberger SLB (DB) Archrock, Inc. AROC (DB) HighPoint Res. HPR (BC) Silverbow SBOW (RM) Baker Hughes BHGE (DB) Hornbeck Offsh HOS (DB) Smart Sand SND (MWM) Basic Energy BAS (DB) Independ. Cont. ICD (DB) Solaris Oilfield SOI (MWM) Berry Petrol. BRY (BC) Innospec Inc IOSP (RS) Southwestern SWN (CM) Bristow Grp BRS (DB) Jones Energy JONE (RM) SRC Energy SRCI (BC) Cabot Oil COG (CM) Key Energy Svcs. KEG (DB) Sundance SNDE (BC) Cactus, Inc. WHD (MWM) Kosmos Energy KOS (CM) Superior Engy SPN (DB) Callon Petl. CPE (RM) Lilis Energy Inc. LLEX (RM) TEAM Inc. TISI (MWM) Carrizo Oil CRZO (RM) Lonestar Res. LONE (RM) TechnipFMC plc FTI (MWM) Centennial Rs CDEV (BC) Mammoth Energy TUSK (DB) TETRA TTI (MWM) Chaparral CHAP (RM) Matador Res. MTDR (BC) Thermon Grp THR (MWM) Chart Industr GTLS (MWM) McDermott Intl. MDR (MWM) Tidewater TDW (RS) Chesapeake CHK (CM) Nabors Industries NBR (DB) Transocean RIG (GV) C&J Energy CJ (DB) National Oilwell NOV (MWM) Unit Corp. UNT (BC) CNX Midstr. CNXM (GV) Newfield Expl NFX (RM) US Silica Hld SLCA (MWM) Comstock CRK (RM) Newpark Res. NR (GV) Weatherford WFT (DB) Concho Res. CXO (CM) Noble Energy NBL (CM) Whiting Pet WLL (BC) Contango MCF (RM) Noble Corp. NE (GV) Wildhorse WRD (BC) Continental Rs CLR (BC) Noble Midstream NBLX (GV) WPX Ergy WPX (BC) Covia Holdings CVIA (MWM) Northern Oil NOG (BC) Core Lab. -

BLM Prohibited Holdings List 2021

BLM 2021 Prohibited Holdings Guide All employees of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) are prohibited from directly or indirectly acquiring interests in Federal lands. This Guide contains information on this prohibition and provides a list of publicly traded stocks that BLM employees, their spouses, and minor or dependent children are prohibited from holding, in the absence of an exception. All BLM employees have a duty to comply with the BLM Organic Act and related ethics regulations. Accordingly, all BLM employees must review their financial investments to ensure that they do not have financial investments in companies on the Prohibited Holding list. Questions may be sent to: [email protected]. Statutory and Regulatory Background Pursuant to the BLM Organic Act (43 U.S.C. § 11) and implementing regulations (43 C.F.R. § 20.401(a); 5 C.F.R. § 3501.103(a)), all BLM employees are prohibited from purchasing or voluntarily acquiring interests in Federal lands. Employees are also barred from owning stock in companies that have interests in Federal lands. 43 C.F.R. § 20.401(2)(B). These prohibitions are designed to avoid conflicts of interest between a BLM employee’s work and his or her personal financial interests and to increase public confidence in the management of Federal lands. Direct interest includes: • Ownership of stocks and other securities that have interests in Federal lands • Participation in earnings from Federal lands; • The right to occupy or use Federal lands; • The right to take any benefit from Federal lands under a contract, grant, lease, permit, easement, rental agreement, or application. -

Williston Quick Look 4-15-2020.Xlsm

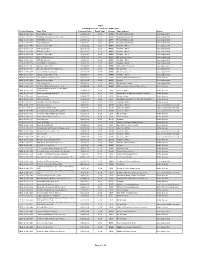

WILLISTON BASIN Wells Put Online Lateral Length (ft) Fluid Intensity (bbls/ft) 6/30/2018 9/30/2018 12/31/2018 3/31/2019 6/30/2018 9/30/2018 12/31/2018 3/31/2019 6/30/2018 9/30/2018 12/31/2018 3/31/2019 OPERATOR SPOTLIGHT 4Q18 1Q19 2Q19 3Q19 4Q18 1Q19 2Q19 3Q19 4Q18 1Q19 2Q19 3Q19 Operator Well Count* CONTINENTAL RESOURCES 507 22 37 36 45 9,690 9,495 9,702 8,523 19 24 22 25 WHITING PETROLEUM 374 41 9 53 40 9,481 7,225 9,027 8,380 20 27 17 18 HESS 355 35 25 39 33 8,236 10,183 9,800 9,993 20 18 18 19 OASIS PETROLEUM 286 28 12 24 18 7,180 4,811 8,515 8,717 30 53 33 28 MARATHON OIL 236 29 19 31 29 5,081 5,161 8,574 8,813 30 18 19 22 EXXON MOBIL 225 7 31 21 19 9,762 10,026 10,048 8,706 40 40 35 31 CONOCOPHILLIPS 212 13 13 13 13 9,825 10,389 9,657 9,699 18 17 21 18 WPX ENERGY 202 20 13 15 23 7,872 9,661 10,331 9,267 21 16 17 12 KRAKEN OPERATING, LLC 169 19 19 18 15 5,844 8,339 7,303 8,121 35 33 30 26 EQUINOR 161 12 11 9 19 8,289 4,422 8,469 9,135 14 24 13 17 EOG RESOURCES 139 7 14 7,313 10,585 25 25 ENERPLUS 120 1 3 26 11 4,102 9,431 9,743 8,960 30 26 18 30 BRUIN E&P PARTNERS 112 11 5 17 7 4,535 9,860 10,797 10,062 49 23 25 26 PETRO-HUNT 107 75445,5377,75510,0498,67456143639 SLAWSON 104 1957810,1103,75414,5449,22623392929 CRESCENT POINT ENERGY U.S. -

FIDELITY COVINGTON TRUST Form NPORT-P Filed 2019-12-24

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM NPORT-P Filing Date: 2019-12-24 | Period of Report: 2019-10-31 SEC Accession No. 0001752724-19-202097 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER FIDELITY COVINGTON TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 245 SUMMER STREET 245 SUMMER STREET CIK:945908| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MA | Fiscal Year End: 1231 BOSTON MA 02210 BOSTON MA 02210 Type: NPORT-P | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-07319 | Film No.: 191307360 6175637000 Copyright © 2019 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Quarterly Holdings Report for Fidelity® MSCI Energy Index ETF October 31, 2019 T03-QTLY-1219 1.9584807.105 Copyright © 2019 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Schedule of Investments October 31, 2019 (Unaudited) Showing Percentage of Net Assets Common Stocks 99.8% Shares Value Shares Value ENERGY EQUIPMENT & SERVICES 10.0% Contura Energy, Inc. (a) 6,356 $145,807 Oil & Gas Drilling 0.8% Peabody Energy Corp. 25,044 263,713 Diamond Offshore Drilling, Inc. (a) 22,900 $121,141 952,341 Helmerich & Payne, Inc. 36,445 1,366,687 Integrated Oil & Gas 44.4% Nabors Industries Ltd. 113,809 210,547 Chevron Corp. 633,620 73,588,627 Noble Corp. PLC (a) 83,595 102,822 Exxon Mobil Corp. 1,407,363 95,095,518 Patterson-UTI Energy, Inc. 69,265 576,285 Occidental Petroleum Corp. 297,566 12,051,423 Transocean Ltd. (a) 172,673 820,197 Unit Corp. (a) 18,007 36,734 Valaris PLC 66,613 273,779 180,772,302 3,471,458 Oil & Gas Exploration & Production 21.3% Oil & Gas Equipment & Services 9.2% Antero Resources Corp. -

NO BAILOUT for FRACKING by Lukas Ross, Senior Policy Analyst at Friends of the Earth, [email protected]

NO BAILOUT FOR FRACKING by Lukas Ross, Senior Policy Analyst at Friends of the Earth, [email protected] KEY FINDINGS ➢ The financial instability of the fracking industry existed long before the coronavirus. At a time of unprecedented emergency, polluters are now poised to benefit from bailout funding in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Econom- ic Security (CARES) Act ➢ 27 major fracking companies began the year “in the red” with negative free cash flow (FCF) and have over $26 billion in Total Current Liabilities due in 2020. This includes interest on debt and other pending obligations. ➢ The CARES Act contains at least $471 billion in lending authority from which frackers and other polluting indus- tries could potentially benefit. Although there are hypothetical conditions attached to corporations receiving government aid, the Treasury Secretary has broad discretion to waive them. The coronavirus is an unprecedented public health emergency. Urgent human needs are going unmet and entire sectors of the economy are collapsing in real time. Resources to help frontline workers and the most vulnerable must be mobilized immediately. In the United States, which now boasts the third highest number of COVID-19 cases in the world, all eyes are on Congress, where a final version of a $2 trillion stimulus bill has finally emerged. Although the CARES Act contains many important provisions providing direct relief to individuals and frontline workers, it worryingly contains a $500 billion corporate slush fund with insufficient guardrails to protect workers, taxpayers and the climate. One industry certainly eyeing this slush fund very carefully is Big Oil, particularly companies heavily invested in fracking. -

2019 Proxy Statement

BE THE BUFFALO Dear Fellow Oasis Petroleum Shareholders, At one of our town hall meetings a few years ago as we were navigating the downturn in our sector, I communicated to our Oasis organization that, when facing an oncoming storm, buffalo will gather together and charge into the storm to get past it, while cattle will tend to run away from the storm. I asked our employees which they’d rather be. Their thundering reply came without hesitation: Be the Buffalo. This has been our rallying cry ever since. Not only are we willing to charge the storm, but we prepare ourselves for the inevitable storm that we know is coming at some point. So, the phrase for us is more than just words, it is how we manage the business and associated risks. For example: • When commodity prices dropped in 2009, others ran away from the storm. We opportunistically added acreage to our large, consolidated blocks in the Williston Basin. • In 2010, reliable and cost-effective services in the Williston Basin were scarce, so we created Oasis Well Services to ensure that we could get our work done and minimize potential contract termination exposure. • Anticipating a potential downturn in commodity price, but not knowing when it might occur, we positioned ourselves to be able to power down our capital activity in an orderly manner, maintain our volume profile, live within cash flow and get to the other side. We did just that and were one of the first, if not the first, Exploration and Production ("E&P") companies to get to cash flow neutral in 2015. -

Katy Start Three Starting Windows Window #1

Katy Start Three Starting Windows Window #1 - 6:45-7:30am Window #2 - 7:30-8:15am Window #3 - 8:15-9:00am Last Name First Name Team Window Abadia Juan 3 Abascal Lesley Team Texas Children's 2 Acevedo Catherine Karbach Brewing Co. 1 Acker Shelley LyondellBasell Cycle Team 1 Acosta Lorenzo BÍK BROS 2 Adams John Saint Arnold Bike Team 1 Adamson Marvin Baker Hughes Express 1 Adegbola Olufemi Baker Hughes Express 1 Adewale Karen Meat Fight 1 Adewole Adekunle Schlumberger Cycling Club 1 Adisa Chris All Day Cycling Club 2 Agar Craig 3 Agrawal Ananya 3 Agrawal Rakesh 3 Agreda Alex Moss Stirling 150 2 Aguilar Carlos Liquor & Wood Bike Crew 2 Aguilar Frankie Meat Fight 1 Aguilera Ruben Dario 3 Aguirre Ignacio STARPAK 2 Ahlgren Jason 3 Ahmed Norris Sagirah Bike Barn 1 Akins TK Motherland Cycling Club 2 Akinwunmi Tosin Team Olin 2 Alanis Aaron Saint Arnold Bike Team 1 Alanis Christian 3 Alanis Marciano Liquor & Wood Bike Crew 2 Albano Brandy Bike Barn 1 alcala jessica LyondellBasell Cycle Team 1 Alexander Helen Saint Arnold Bike Team 1 Alexander Steven Karbach Brewing Co. 1 Ali Noman Aga Khan Foundation Southwest Bikers 2 Allbritton Daniel AIG Bike Team 2 Allen Edgar 3 Allen Jacqueline DXP Cycling Team 2 Allen John Pushin Watts 3 Allen Rebecca Team Hines 2 allen rodric Pushin Watts 3 Allen Stephen 3 Allen Timothy Phillips 66 1 Allsobrook Geoffrey Team Noble Drilling 1 Almeida Eric Adam STARPAK 2 Alrashed Khalid Team Wood 1 Alvarado Orlando Saint Arnold Bike Team 1 Alvarenga Gerson Handlebar Bicycle Club 2 Alvarez Adam BÍK BROS 2 Katy Start Three -

Of 10 IBLA Pending Cases As of July 31, 2020 | 597 Docket Number Case Title Docketed Date Fiscal Year Bureau Case Subject Status IBLA-2016-0275 Thomas E

IBLA Pending Cases as of July 31, 2020 | 597 Docket Number Case Title Docketed Date Fiscal Year Bureau Case Subject Status IBLA-2013-0028 Shell Offshore, Inc. 11/21/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty Fairness Act Case suspended IBLA-2013-0035 McMoRan Oil and Gas LLC, et al. 12/3/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty Fairness Act Case suspended IBLA-2013-0042 W&T Offshore, Inc. 12/6/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty Fairness Act Case suspended IBLA-2013-0043 XTO Energy Inc. 12/6/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty Fairness Act Case suspended IBLA-2013-0049 Apache Corporation 12/7/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0051 XTO Energy Inc. 12/10/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0052 XTO Energy Inc. 12/10/2012 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0089 Apache Corporation 3/8/2013 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0100 W & T Offshore, Inc. 3/18/2013 2013 ONRR Oil and Gas Lease Case suspended IBLA-2013-0118 XTO Energy, Inc. 4/9/2013 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0119 ExxonMobil Corporation 4/9/2013 2013 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2013-0190 Apache Corporation 7/29/2013 2013 ONRR Demand for Payment Case suspended IBLA-2014-0110 BP Exploration & Production Inc. 3/10/2014 2014 ONRR Oil and Gas Case suspended IBLA-2014-0265 ConocoPhillips Company 9/10/2014 2014 ONRR Oil and Gas Lease Case suspended IBLA-2014-0284 Apache Corporation et al. 9/18/2014 2014 ONRR Royalty - Other Case suspended IBLA-2014-0287-1 06 Livestock Company, et al. -

The 19Th Annual Energy Conference Recap

The 19th Annual Energy Conference Recap Piper Jaffray does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decisions. This report should be read in conjunction with important disclosure information, including an attestation under Regulation Analyst Certification, found at the end of this report or at the following site: http://www.piperjaffray.com/researchdisclosures. THE 19TH ANNUAL ENERGY CONFERENCE RECAP FEBRUARY 26–28, 2019 | LAS VEGAS, NV Participants REFINING PANEL OFS INTERNATIONAL PANEL SMID-CAP OIL SERVICE PANEL Rich Voliva Owen Kratz C. Christopher Gaut EVP & CFO President & CEO Chairman & CEO HollyFrontier Corporation (HFC) Helix Energy Solutions Group (HLX) Forum Energy Technologies (FET) Erik Young Cindy Taylor Kevin Neveu CFO President & CEO President & CEO PBF Energy Inc. (PBF) Oil States International (OIS) Precision Drilling Corporation (PDS) Kevin Mitchell Dave Dunlap Joel Broussard EVP, Finance & CFO President & CEO President & CEO Phillips 66 (PSX) Superior Energy Services (SPN) U.S. Well Services Inc. (USWS) COMPLETION SERVICES PANEL E&P SMID DIVERSIFIED BASIN PANEL E&P INTEGRATED PANEL Scott Bender Taylor Reid Bjørn Inge Braathen President & CEO President & COO SVP Exploration North America Cactus, Inc. (WHD) Oasis Petroleum (OAS) Equinor ASA (EQNR) Ron Gusek Lynn Peterson Roger Jenkins President President & CEO President & CEO Liberty Oilfield Services, Inc. (LBRT) SRC Energy Inc. (SRCI) Murphy Oil Corp. (MUR) Ann Fox President & CEO PRIVATE EQUITY PANEL NATURAL GAS PANEL Nine Energy Services, Inc. -

Building a Stronger, Sustainable Oasis with Strategic Acquisition in Williston Basin

Building a Stronger, Sustainable Oasis with Strategic Acquisition in Williston Basin May 2021 A New Tomorrow, Today A New Tomorrow, Today Nasdaq: OAS Forward-Looking / Cautionary Statements Forward-Looking Statements Non-GAAP Financial Measures This presentation, including the oral statements made in connection herewith, contains forward-looking statements Cash Interest, Adjusted EBITDA, E&P Cash G&A, Free Cash Flow, Adjusted Net Income (Loss) Attributable to Oasis, Adjusted within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of Diluted Earnings (Loss) Attributable to Oasis Per Share and Recycle Ratio are supplemental financial measures that are not 1934. All statements, other than statements of historical facts, included in this presentation that address activities, presented in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles in the United States (“GAAP”). These non-GAAP measures events or developments that the Company expects, believes or anticipates will or may occur in the future are should not be considered in isolation or as a substitute for interest expense, net income (loss), operating income (loss), net cash forward-looking statements. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, forward-looking statements contained in provided by (used in) operating activities, earnings (loss) per share or any other measures prepared under GAAP. Because Cash this presentation specifically include the expectations surrounding the closing of the Simplification as well as -

2020.2 OAS Presentation.Vf2.Pdf

February 2020 Investor Presentation Forward-Looking / Cautionary Statements Forward-Looking Statements Non-GAAP Financial Measures This presentation, including the oral statements made in connection herewith, contains Cash Interest, Adjusted EBITDA, E&P Cash G&A, Free Cash Flow, Adjusted Net Income (Loss) forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 Attributable to Oasis, Adjusted Diluted Earnings (Loss) Attributable to Oasis Per Share and Recycle and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. All statements, other than Ratio are supplemental financial measures that are not presented in accordance with generally statements of historical facts, included in this presentation that address activities, events or accepted accounting principles in the United States (“GAAP”). These non-GAAP measures should not developments that the Company expects, believes or anticipates will or may occur in the be considered in isolation or as a substitute for interest expense, net income (loss), operating income future are forward-looking statements. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, (loss), net cash provided by (used in) operating activities, earnings (loss) per share or any other forward-looking statements contained in this presentation specifically include the expectations measures prepared under GAAP. Because Cash Interest, Adjusted EBITDA, Free Cash Flow, of plans, strategies, objectives and anticipated financial and operating results of the Adjusted Net Income (Loss) Attributable to Oasis, Adjusted Diluted Earnings (Loss) Attributable to Company, including the Company's drilling program, production, derivative instruments, Oasis Per Share and Recycle Ratio exclude some but not all items that affect net income (loss) and capital expenditure levels and other guidance included in this presentation.