Issue-Two Box-Of-Tricks.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Historia 2. Carrera Musical

Queen Banda de rock británica formada por Freddie Mercury (voz), Brian May (guitarra), Roger Taylor (batería) y John Deacon (bajo). El grupo gozó de gran fama a finales de los setenta y durante toda la década de los ochenta, y sus discos fueron superventas incluso después del fallecimiento en 1991 de Freddie Mercury, víctima del SIDA. 1. Historia 1.1. Orígenes Sus orígenes se remontan al inicio de los sesenta, cuando el joven guitarrista Brian Harold May (nacido en 1947) comenzó a tocar en un grupo semiprofesional llamado 1984. Brian, experto conocedor de varios instrumentos de cuerda, diseñaba incluso sus propias guitarras, conocidas posteriormente como el modelo Red Special. Brian May pasó después a formar parte de otra banda, llamada Smile, con la que editó un single. Inesperadamente, Tim Stafell, el cantante de la banda, abandonó el grupo; para buscar su sustituto, los miembros de Smile decidieron hacer una prueba al cantante de Sour Milk Sea, que no era otro que Freddie Mercury, y fue rápidamente admitido. 1.2. Freddy Por aquel entonces Freddie Mercury ya estaba acostumbrado a aparecer en público y sobre el escenario con vestimentas llamativas y atrevidas. Freddie contaba con una prodigiosa voz y sobrados conocimientos de piano. A esto se unió una base rítmica firmada por John Richard Deacon (nacido en 1951) al bajo y la batería de Roger Meadows Taylor (nacido en 1949). 2. Carrera musical 2.1. Primer trabajo El grupo comenzó a grabar maquetas y la compañía discográfica EMI, después de verlos actuar en el Marquee de Londres, se interesó por ellos. -

Belfast Festival 2012 Programme

19 october - 4 november 2012 FESTIVAL Programme 02 CONTENTS 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s WELCOME 03 INTRO 03 C Classical celebrate 04 Com Comedy Anthology 08 D Dance world classy 10 F Film engage 19 Fam Family homegrown 24 T Talks the beautiful game 28 TH Theatre let’s dance 31 TWJP Trad/World/Jazz/Pop headliners 36 SA Sonic Arts delight 40 VA Visual Arts WELCOME INTRODUCTION mexico 48 The 50th Festival. What an exciting season. What a The 50th Belfast Festival at Queen’s presents the re-imagine 50 wonderful achievement. opportunity to reflect on what has been achieved over In 1961 a group of young Queen’s students organised the the years and to remember what makes this cultural graphic grrRls 54 first arts festival at the University. Modest in scope compared extravaganza so special. It is breath-taking to consider the to today, it nonetheless shone with ambition and it had a number of people who, over the last five decades, have innovate 56 sense of purpose - only the best will do. played their part in creating Festival’s cultural legacy. From those early days the Queen’s Festival - now the Ulster From artists and performers, venues and audiences, inspire 61 Bank Belfast Festival at Queen’s - has indeed been bringing volunteers and staff through to our patrons and supporters us the best, and in doing so it has placed this city firmly on all have helped Festival on its journey and ensured that it 50 shades of green 64 the map as a centre of cultural importance. -

Book of Idioms from a to Z

Aa A abdabs A 1 excellent; first-rate. give someone the screaming abdabs induce an attack of extreme anxiety or irritation in i O The full form of this expression is >47 at ! Lloyd's. In Lloyd's Register of Shipping, the someone. j phrase was used of ships in first-class j O Abdabs (or habdabs) is mid 20th-century ! I condition as to the hull (A) and stores (1). The ! slang whose origin is unknown. The word is ! US equivalent is A No. 7; both have been in j sometimes also used to mean an attack of ; figurative use since the mid 19th century. j delirium tremens. from A to B from your starting point to your destination; from one place to another. abet 1987 K. Rushforth Tree Planting & Managementai d and abet: see AID. The purpose of street tree planting is to... make the roads and thoroughfares pleasant in their own right, not just as places about used to travel from A to B. know what you are about be aware of the from A to Z over the entire range; in every implications of your actions or of a particular. situation, and of how best to deal with 1998 Salmon, Trout & Sea-Trout In order to have them, informal seen Scotland's game fishing in its entirety, 1993 Ski Survey He ran a 3-star guest house from A to Z, visiting 30 stretches of river and before this, so knows what he is about. 350 lochs a year, you would have to be travelling for a hundred years. -

Billboard-1975-12-06

08120 NEWSPAPER ;Sr110éR «76 tt* 156 151 R BB R SNYDER 3639 MARY A'JN 9R LEBANON 3036 81 St YEAR A Billboard Publication The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly December 6, 1975 $1 50 Ford Foundation In Disco Tour NEW DISK FORMULA? $180,000 Disk Outlay Sets Target L.A. Philharmonic By IS HOROWITZ Of 23 Cities NEW YORK -The Ford Founda- Atlantic's Glew By JIM MELANSON tion has disbursed $- 80,000 to 15 la- NEW YORK -A disco -themed Contract Disputed bels in the first nine months of its dance /concert package created by program to stimulate commercial Forum Keynoter Drew Cummings and quietly sup- By ROBEFT SOBEL recordings of serious works by living NEW YORK -'I he keynote ported by the Dimples discotheque GRC Assets Sold NEW YORK -Jos Angeles Phil- American composer;. speaker at the opening session of chain is being offered to arenas harmonic Orchestra management So far more than 40 LPs bearing Billboard's first International Disco throughout the East by the William To L.A. Agency claims it has achieved a union con- sponsored performances are being ForLm will be David Glew, vice Morris Agency. tract breakthrough providing that processed or have a ready been re- president of Atlantic Records. With the go -ahead signal given By DAVE DEXTER JR. only musicians taking part in leased. Glew's subject will be "Disco last week, the parties involved have LOS ANGELES -Sale of General recordings be paid for the session. Total commitment of the founda- Power: Myth Or Reality ?" (Continued on page 12) Recording Co.'s assets to the Ameri- The national symphonic formula tion project is $400,(00, and it is due The Forum opens at the Roosevelt can Variety International Agency requires all members of an estab- to run for three years or until the as- Hotel here Jan. -

Queen Rainbow Theatre '74 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Queen Rainbow Theatre '74 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Rainbow Theatre '74 Country: Japan Style: Classic Rock, Glam, Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1719 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1703 mb WMA version RAR size: 1690 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 543 Other Formats: MIDI ADX AHX VOX DXD MOD VQF Tracklist 1 Procession (Taped Intro) 2 Now I'm Here 3 Ogre Battle 4 White Queen 5 Medley - In The Lap Of The Gods 6 Medley - Killer Queen 7 Medley - March Of The Black Queen 8 Medley - Bring Back That Leroy Brown 9 Son And Daughter 10 Guitar Solo 11 Father To Son 12 Keep Yourself Alive 13 Liar 14 Son And Daughter (Reprise) 15 Stone Cold Crazy 16 In The Lap Of The Gods...Revisited 17 Jailhouse Rock 18 God Save The Queen (Tape) Notes Recorded live at the Rainbow Theatre, London UK, Nov. 19th.& 20th. 1974. Taken from the official VHS video 'Live at the Rainbow' from 'Box Of Tricks' released in 1992. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year At The Rainbow (DVDr, DVD-V, Not On Label none Queen none Japan 2011 Unofficial, NTSC) (Queen) Rainbow 1974 (DVDr, DVD-V, none Queen Wardour none Japan 2008 Unofficial, NTSC) Live At The Rainbow 1974 200 GR-CV M Queen Green Ray 200 GR-CV M Russia 2011 (DVD-V, Unofficial, PAL) Related Music albums to Rainbow Theatre '74 by Queen Queen - In The Lap Of The Queen Queen - Alive 1979 Queen - Modern Times Rock 'N' Roll Kween - World Tour 2005 (The 70's Queen Tribute Live) Queen - A Night At The Court Queen - Live At The Rainbow '74 Queen - Look Back In Anger Queen - Melbourne 1985. -

Billboard 1974-03-30

IVSIVSPAFER 08120 TWO SECTIONS, SECTION ONE MARCH 30, 1974 $1.25 A BILLBOARD PUBLICATION EIGHTIETH YEAR The International Music- Record Tape Newsweekly TAPE /AUDIO /VIDEO PAGE 56 HOT 100 PAGE 108 TOP LP'S PAGES 110, 112 All-Star U.S. Line -Up Sooner Group NARM Meet to Be To Participate at IMIC Wins Senate Biggest; Retailer NEW YORK -An impressive ar- can Society of Composers, Authors ray of U.S. music- record industry & Publishers, will discuss the U.S. li- Piracy Bill OK leaders will participate in the fifth censing organization's newly -con- Attendance Rises International Music Industry Con- ceived "ASCAP Think Tank." By JOHN SIPPEL By IS HOROWITZ ference, to be held at the Grosvenor Ed Cramer, president, Broadcast OKLAHOMA CITY dedi- -A HOLLYWOOD, Fla.- Advance estimated 65 percent of attendees. House, London, May 7 -10. IMIC is Music, Inc., will deliver a report on cated campaign by a handful of state contingents of industry executives All major manufacturers were due held under the auspices of the "The U.S. Copyright Act Revision - supporters of the antipiracy propos- representing every facet of the to be represented as well. worldwide Billboard Publishing An Update." al. seemingly delayed a year before record and tape marketing spectrum Total attendance was expected to Group (Billboard, High Fidelity, Bobby Brenner, Bobby Brenner consideration by the state legislature began arriving here late last week to top 1,400 at the series of meetings Music Labo, Music Week). Associates, will serve as chairman of (Billboard, Mar. 23), brought pas- participate in what was shaping up scheduled to run at the Diplomat Stanley Adams, president, Ameri- the seminar devoted to "Sound Tal- sage of the proposal last week by the as the largest and perhaps most pro- (Continued on page /3) ent Management." Seymour Heller, Senate here. -

Tom Burgoon PAGE 36

APRIL 2012 Tom Burgoon PAGE 36 M-U-M APRIL 2012 MAGAZINE Volume 101 • Number 11 S.A.M. NEWS 6 From the Editor’s Desk 8 From the President’s Desk 11 M-U-M Assembly News 23 Good Cheer List 23 New Members 24 Broken Wands 26 Newsworthy ON THE COVER PAGE 36 63 Our Advertisers 28 THIS MONTH’S FEATURES 62 Bruce Chadwick’s Magical Wisdom 34 Ellipsis • by Michael Perovich 36 COVER STORY • by Bruce Kalver, PNP 40 More from Tom Burgoon 52 42 The Houdini Fund • George Schindler 44 Salon de Magie • by Ken Klosterman 46 A Magician Prepares • by Dennis Loomis 68 48 Magic From Scotland • Edited by Ian Kendall 52 Nielsen Gallery: Leon - Fire and Water. • by Tom Ewing 54 Informed Opinion • New Product Reviews 68 Basil the Baffling • by Alan Wassilak COLUMNISTS 28 Stage 101 • by Levent 30 I Left My Cards at Home • by Steve Marshall 45 Tech Tricks • by Bruce Kalver 63 Inside Straight • by Norman Beck 64 Pro Files • by James Munton 66 Theory & Art of Magic • by Larry Hass 68 The Dean’s Diary • by George Schindler 70 Confessions of a Paid Amateur • by Rod Danilewicz Cover Photo by Jami Nato 52 M-U-M (ISSN 00475300 USPS 323580) is published monthly for $40 per year by The Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr., Parker, CO 80134 . Periodical postage paid at Parker, CO and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to M-U-M, c/o Manon Rodriguez, P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134. -

The Queen Discography Completa (1973-1991) Aggiornata (1992-2020)

The Queen Discography Completa (1973-1991) Aggiornata (1992-2020) - Studio Albums: Queen (13 Jul 1973) Queen II (8 Mar 1974) Sheer Heart Attack (8 Nov 1974) A Night At The Opera (21 Nov 1975) A Day At The Races (10 Dec 1976) News Of The World (28 Oct 1977) Jazz (10 Nov 1978) The Game (27 Jun 1980) Flash Gordon (8 Dec 1980) Hot Space (21 May 1982) The Works (27 Feb 1984) A Kind Of Magic (3 Jun 1986) The Miracle (22 May 1989) Innuendo (5 Feb 1991) Made In Heaven (6 Nov 1995) - Live Albums: Live Killers (rec: Jan–Mar 1979) (22 Jun 1979) Live Magic (rec: July–Aug 1986) (1 Dec 1986) At The Beeb (rec: 5 Feb & 3 Dec 1973) (4 Dec 1989) Live At Wembley '86 (rec: 12 Jul 1986) (26 May 1992) Queen On Fire – Live At The Bowl (rec: 5 Jun 1982) (4 Nov 2004) Queen Rock Montreal (rec: 24 & 25 Nov 1981) (29 Oct 2007) Hungarian Rhapsody: Queen Live In Budapest (rec: 27 Jul 1986) (20 Sep 2012) Live At The Rainbow '74 (rec: 31 Mar, 19 & 20 Nov 1974) (8 Sep 2014) A Night At The Odeon – Hammersmith 1975 (rec: 24 Dec 1975) (20 Nov 2015) On Air (rec BBC: Feb 1973 - Oct 1977) (4 Nov 2016) - Singles: Keep Yourself Alive / Son And Daughter (6 Jul 1973) Seven Seas Of Rhye / See What A Fool I've Been * (25 Feb 1974) Killer Queen / Flick Of The Wrist (single version) * (11 Oct 1974) Now I'm Here / Lily Of The Valley (single edit) * (17 Jan 1975) Bohemian Rhapsody (single edit) * / I'm In Love With My Car (single version) * (31 Oct 1975) You're My Best Friend / ‘39 (single edit) * (18 Jun 1976) Somebody To Love / White Man (19 Nov 1976) Tie Your Mother Down (single -

Razorcake Issue #81 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

WRAP Theses Turner 2018.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/117251 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Box of Tricks: A Critical Analysis of Twenty- First Century Televised Performance Magic by Elizabeth Clair Turner A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre and Performance Studies University of Warwick, School of Theatre & Performance Studies and Cultural & Media Policy Studies March 2018 Contents List of illustrations ........................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 5 Declaration ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction: performance magic on television ....................................................................... -

Rory Feldman Page 36

NOVEMBER 2012 RORY FELDMAN PAGE 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Fax: 866-591-7392 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - NOVEMBER 2012 M-U-M NOVEMBER 2012 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 6 S.A.M. NEWS 6 From the Editor’s Desk 8 From the President’s Desk 64 11 M-U-M Assembly News 24 Good Cheer List 30 Newsworthy -

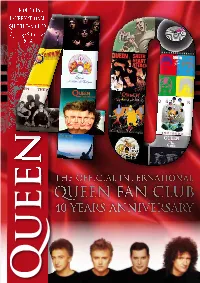

Qfc-Mag-Summer-2014-Print.Pdf

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Spring/Summer 2014 Editorial From Queen to You Hi Everyone! „Queen and Adam Lambert have managed to ace the nerve-wracking first night of their tour I hope you are all well and happy wherever you are? Apologies for the delay in this issue - it in North America, rocking Chicago‘s United Center to its foundations with a bombastic rock has been manic in the fan club since the start of the year! When the North American/Canadian show to surpass all others.“ - Contactmusic.com All Pictures: Neal Preston tour was announced, I had about a thousands new members within the space of a week, and I am STILL trying to get them all entered into the database and sent out... then they „The show epitomized Queen, in all its flamboyant glory“ - announced Korea and Japan, then Australia! More new members! But I am not complai- Chicago Tribune. ning, it will ensure the fan club stays alive for a bit longer yet! Big thanks to Jim Jenkins for the fabulous article in this issue about the fan club and our Chicago, June 19, 2014 40 year reign! I am amazed at what we have managed to achieve in those 40 years (I have ‚only‘ done it for 32 of them...!). What a Queen year so far! I have seen footage of the shows - just AWESOME! The iHeart Radio show in Los Angeles on June 16th was quite brilliant - hopefully you have caught that on YouTube by now! Fingers crossed for dates THIS side of the pond in Europe and the UK! Obviously should I hear anything I will make sure you all know about it! Just make sure you are registered on our members website - www.queenmembers.com.