Cloud Stories Cloud Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

The Secrets of the Best Rainbows on Earth Steven Businger

Article The Secrets of the Best Rainbows on Earth Steven Businger ABSTRACT: This paper makes a case for why Hawaii is the rainbow capital of the world. It begins by briefly touching on the cultural and historical significance of rainbows in Hawaii. Next it provides an overview of the science behind the rainbow phenomenon, which provides context for exploring the meteorology that helps explain the prevalence of Hawaiian rainbows. Last, the paper discusses the art and science of chasing rainbows. KEYWORDS: Tropics; Atmospheric circulation; Dispersion; Orographic effects; Optical phenomena; Machine learning https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0101.1 Corresponding author: Dr. Steven Businger, [email protected] In final form 15 October 2020 ©2021 American Meteorological Society For information regarding reuse of this content and general copyright information, consult the AMS Copyright Policy. AFFILIATION: Businger—University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawaii AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY FEBRUARY 2021 E1 ainbows are some of the most spectacular R optical phenomena in the natural world, and Hawaii is blessed with an amazing abundance of them. Rainbows in Hawaii are at once so common and yet so stunning that they appear in Hawaiian chants and legends, on license plates, and in the names of Hawaiian sports teams and local businesses (Fig. 1). Visitors and locals alike frequently leave their cars by the side of the road in order to photograph these brilliant bands of light. Fig. 1. Collage of Hawaii rainbow references. The cultural importance of rainbows is reflected in the Hawaiian language, which has many words and phrases to describe the variety of manifestations in Hawaii, a few of which are provided in Table 1. -

AC 00-57 Hazardous Mountain Winds

AC 00-57 Hazardous Mountain Winds And Their Visual Indicators U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Federal Aviation Administration Office of Communications, Navigation, and Surveillance Systems Washington, D.C. FOREWORD This advisory circular (A C) contains Comments regarding this publication information on hazardous mountain winds should be directed to the Department of and their effects on flight operations near Transportation, Federal Aviation mountainous regions. The primary Administration, Flight Standards purpose of thls AC is to assist pilots Service, Technical Programs Division, involved in aviation operations to 800 Independence Avenue, S.W. diagnose the potential for severe wind Washington, DC 20591. events in the vicinity of mountainous areas and to provide information on pre-flight planning techniques and in-flight evaluation strategies for avoiding destructive turbulence and loss of aircraft control. Additionally, pilots and others who must deal with weather phenomena in aviation operations also will benefit from the information contained in this AC. Pilots can review the photographs and section summaries to learn about and recognize common indicators of wind motion in the atmosphere. The photographs show physical processes and provide visual clues. The summaries cover the technical and "wonder" aspects of why certain things occur what caused it? How does it affect pre-flight and in-flight decisions? The physical aspects are covered more in-depth through the text. v Acknowledgments Thomas Q. Carney Purdue University, Department of Aviation Technology and Consultant in Aviation Operations and Applied Meteorology A. J. Bedard, Jr. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental Technology Laboratory John M. Brown National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Forecast Systems Laboratory John McGinley National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Forecast Systems Laboratory Tenny Lindholm National Center for Atmospheric Research Research Applications Program Michael J. -

Talking Points for “Satellite Interpretation of Orographic Clouds / Effects”

Talking points for “Satellite Interpretation of Orographic clouds / effects” 1. Title page 2. Objectives 3. Topics 4. Gap wind event over New Mexico. Strong winds affect Albuquerque and introduce moist airmass which may impact convective forecast the next day. 5. Topography of New Mexico. In easterly flow, winds may be funneled through Tijeras gap east of Albuquerque and produce locally strong winds in the city. 6. Surface observations (METARs) from 00:00 – 12:00 UTC (3 hour increments) 12 June 1999. At 00:00 UTC we observe a warm and dry air mass and southwest flow over most of central New Mexico (including Albuquerque). As time goes on, the easterly flow advects westward. Eventually, the easterly flow makes it to Albuquerque where the dewpoint goes from the 20’s to the low 50’s. The gap wind effects are very localized, at the Albuquerque airport winds gusted up to 30 mph, while on the west side of town at Double Eagle airport winds were southeast at 10 mph. 7. Fog Product 02:46 – 10:30 UTC 12 June 1999. This loop shows the origin of the easterly flow which helped produce the gap winds in Albuquerque. Deep convection on the plains of eastern New Mexico produced strong outflow that moved westward. Since this loop is at night, we can utilize the fog product to identify the outflow boundaries readily. The fog product is good at distinguishing low-level outflow boundaries at night. The outflow pushes westward towards Albuquerque, as it reaches the Tijeras gap the gap wind event begins. The fog product can be used in this way (at night) to determine when the conditions favorable for gap winds will begin. -

Classification of Clouds Clouds Are Usually Classified According to Their Height and Appearance

CLOUDS Clouds are condensed droplets of water and ice crystals. The nuclei of those droplets are dust particles. Near the surface these drops form fog and in the free atmosphere, they form clouds. Clouds have been defined as visible aggregation of minute water droplets and / or ice particles in the air, usually above the general ground level. Air contains moisture and this is extremely important to the formation of clouds. Clouds are formed around microscopic particles such as dust, smoke, salt crystals & other materials that are present in the atmosphere. These materials are called Cloud Condensation Nucleus (CCN). Without these, no cloud formation will take place. There are certain special types, known as ice nucleus, on which droplets freeze or ice crystals form directly from water vapour. Generally condensation nuclei are present in plenty in air. But there is scarcity of special ice forming nuclei. Generally clouds are made up of billion of these tiny water droplets or ice crystals or combination of both. When a current of air rises upwards due to increased temperature it goes up, expands and gets cooled. If the cooling continues till the saturation point is reached, the water vapour condenses and forms clouds. The condensation takes place on a nucleus of dust particles. The water particles individually are very small and suspended in the air. Only when the droplets coalesce to from a drop of sufficient weight, to overcome the resistance of air, they fall as rain. Clouds are considered essential and accurate tools for weather forecasting. Classification of clouds Clouds are usually classified according to their height and appearance. -

Metar Abbreviations Metar/Taf List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

METAR ABBREVIATIONS http://www.alaska.faa.gov/fai/afss/metar%20taf/metcont.htm METAR/TAF LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS $ maintenance check indicator - light intensity indicator that visual range data follows; separator between + heavy intensity / temperature and dew point data. ACFT ACC altocumulus castellanus aircraft mishap MSHP ACSL altocumulus standing lenticular cloud AO1 automated station without precipitation discriminator AO2 automated station with precipitation discriminator ALP airport location point APCH approach APRNT apparent APRX approximately ATCT airport traffic control tower AUTO fully automated report B began BC patches BKN broken BL blowing BR mist C center (with reference to runway designation) CA cloud-air lightning CB cumulonimbus cloud CBMAM cumulonimbus mammatus cloud CC cloud-cloud lightning CCSL cirrocumulus standing lenticular cloud cd candela CG cloud-ground lightning CHI cloud-height indicator CHINO sky condition at secondary location not available CIG ceiling CLR clear CONS continuous COR correction to a previously disseminated observation DOC Department of Commerce DOD Department of Defense DOT Department of Transportation DR low drifting DS duststorm DSIPTG dissipating DSNT distant DU widespread dust DVR dispatch visual range DZ drizzle E east, ended, estimated ceiling (SAO) FAA Federal Aviation Administration FC funnel cloud FEW few clouds FG fog FIBI filed but impracticable to transmit FIRST first observation after a break in coverage at manual station Federal Meteorological Handbook No.1, Surface -

Chapter 6 Clouds

Chapter 6 Clouds Chapter overview • Processes causing saturation o Cooling, moisturizing, mixing • Cloud identification and classification • Cloud Observations • Fog Why do we care about clouds in the atmosphere? Cloud Development Clouds form when air becomes saturated. How can unsaturated air become saturated? • Cooling • Adding moisture • Mixing Cooling and moisturizing The amount of cooling needed for air to become saturated is given by ΔT = Td - T The amount of additional moisture needed for air to become saturated is given by Δr = rs - r The change in temperature (ΔT) or the change in moisture (Δr) can be determined by evaluating the heat or moisture budget of an air parcel. Most clouds form as a result of rising air. How does the temperature and relative humidity of an air parcel change as it rises adiabatically? What processes are responsible for causing air to rise? Cumuliform clouds form in air that rises due to its buoyancy. Stratiform clouds form in are that is forced to rise. Mixing Mixing of two unsaturated air parcels can result in a saturated mixture. Why can the mixing of unsaturated air result in air becoming saturated? What are some examples of air becoming saturated in this way? The temperature and mixing ratio of the mixture can be calculated using: mx = mB + mC mBTB + mCTC Tx = mx mBrB + mCrC rx = mx Where the m is the mass of the air parcel, subscripts B and C indicate the two original air parcels, and subscript X indicates the mixture. Vapor pressure or specific humidity can be used in place in mixing ratio. -

Clouds and Precipitation

Chapter 9 CLOUDS AND PRECIPITATION Fire weather is usually fair weather. Clouds, fog, and precipitation do not predominate during the fire season. The appearance of clouds during the fire season may have good portent or bad. Overcast skies shade the surface and thus temper forest flammability. This is good from the wildfire standpoint, but may preclude the use of prescribed fire for useful purposes. Some clouds develop into full-blown thunderstorms with fire-starting potential and often disastrous effects on fire behavior. The amount of precipitation and its seasonal distribution are important factors in controlling the beginning, ending, and severity of local fire seasons. Prolonged periods with lack of clouds and precipitation set the stage for severe burning conditions by increasing the availability of dead fuel and depleting soil moisture necessary for the normal physiological functions of living plants. Severe burning conditions are not erased easily. Extremely dry forest fuels may undergo superficial moistening by rain in the forenoon, but may dry out quickly and become flammable again during the afternoon. 144 CLOUDS AND PRECIPITATION Clouds consist of minute water droplets, ice crystals, or a mixture of the two in sufficient quantities to make the mass discernible. Some clouds are pretty, others are dull, and some are foreboding. But we need to look beyond these aesthetic qualities. Clouds are visible evidence of atmospheric moisture and atmospheric motion. Those that indicate instability may serve as a warning to the fire-control man. Some produce precipitation and become an ally to the firefighter. We must look into the processes by which clouds are formed and precipitation is produced in order to understand the meaning and portent of clouds as they relate to fire weather. -

The Ten Different Types of Clouds

THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE TEN DIFFERENT TYPES OF CLOUDS AND HOW TO IDENTIFY THEM Dedicated to those who are passionately curious, keep their heads in the clouds, and keep their eyes on the skies. And to Luke Howard, the father of cloud classification. 4 Infographic 5 Introduction 12 Cirrus 18 Cirrocumulus 25 Cirrostratus 31 Altocumulus 38 Altostratus 45 Nimbostratus TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 51 Cumulonimbus 57 Cumulus 64 Stratus 71 Stratocumulus 79 Our Mission 80 Extras Cloud Types: An Infographic 4 An Introduction to the 10 Different An Introduction to the 10 Different Types of Clouds Types of Clouds ⛅ Clouds are the equivalent of an ever-evolving painting in the sky. They have the ability to make for magnificent sunrises and spectacular sunsets. We’re surrounded by clouds almost every day of our lives. Let’s take the time and learn a little bit more about them! The following information is presented to you as a comprehensive guide to the ten different types of clouds and how to idenify them. Let’s just say it’s an instruction manual to the sky. Here you’ll learn about the ten different cloud types: their characteristics, how they differentiate from the other cloud types, and much more. So three cheers to you for starting on your cloud identification journey. Happy cloudspotting, friends! The Three High Level Clouds Cirrus (Ci) Cirrocumulus (Cc) Cirrostratus (Cs) High, wispy streaks High-altitude cloudlets Pale, veil-like layer High-altitude, thin, and wispy cloud High-altitude, thin, and wispy cloud streaks made of ice crystals streaks -

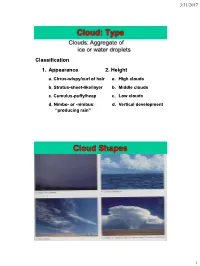

Type Clouds: Aggregate of Ice Or Water Droplets Classification 1

3/31/2017 Cloud: Type Clouds: Aggregate of ice or water droplets Classification 1. Appearance 2. Height a. Cirrus-wispy/curl of hair a. High clouds b. Stratus-sheet-like/layer b. Middle clouds c. Cumulus-puffy/heap c. Low clouds d. Nimbo- or -nimbus: d. Vertical development “producing rain” Cloud Shapes 1 3/31/2017 Different Kinds of Cloud Clouds has been defined as a visible aggregation of minute water droplets and / or ice particles in the air, usually above the general ground level. A. High (mean heights 6 to 13 km) (Mean lower level 20000 ft) i) Cirrus (ci) ii) Cirrocumulus (cc) iii) Cirrostratus(cs) B. Middle (Mean heights 2 to 7 km) (6500 to 20000') i) Altostratus (As) ii) Altocumulus (Ac) C. Low (mean heights < 2 km) (Close to earth's surface to 6500') i) Nimbostratus (Ns) ii) Stratocumulus (Sc) iii) Stratus (St) iv) Cumulus (Cu) (Also Vertical Cloud) v) Cumulonimbus(Cn) (Also Vertical Cloud) High Clouds Above 6000 meters (20,000 feet) to 12,000 meters (top troposphere) Height a little dependent on temperature Lower for colder surface temperatures Composed of ice crystals (ave. temp. -35°C) Little water vapor at these temperatures 1. Cirrus (Ci) 2. Cirrostratus (Cs) 3. Cirrocumulus (Cc) 2 3/31/2017 High Clouds - Cirrus Above 6000 meters (20,000 feet) Cirrus (Ci) Thin, wispy, detached filaments, or fibrous (Hair like) clouds of ice (curl or lock of hair) “Mare’s tail” Simplest 1.5 km thick Little water vapor - 0.025 g/m3 Individual ice crystals - 8mm (0.3in) Fall at speeds of 0.5 m/s (1 mi /hr) making streaks Falling ice sublimates -

MET 200 Lecture 7 Cloud Forms Colorado's “Biblical”

MET 200 Lecture 7 Cloud Forms Cloud forms and what they tell us. 1 2 Colorado’s “biblical” flood Colorado’s “biblical” flood 3 4 230.6 mm (9.08 in) Colorado’s “biblical” flood Boulder Co. Flood Estimating the return interval of the Boulder Flood 5 6 Boulder Co. Flood Boulder Co. Flood Rainfall amounts for the seven days ending at noon MDT on Friday, September 13, ranged from 5 to 10-plus inches across large swaths of the Colorado Front Range, with similar amounts eastward into northwest Kansas. 7 8 Boulder Co. Flood Boulder Co. Flood • Boulder’s previous record for wettest calendar day—4.80” (July 31, 1919)—was shattered. • The single day of rain on Thursday was also nearly twice as much as any other entire September has produced (5.50”, in 1940). • The full week’s rainfall easily topped the 9.59” observed in May 1995, Boulder’s wettest month up to now. Between 00Z Thursday 9/12 (6 PM Mountain Daylight Time on • This week’s precipitation also exceeded the 12.96” that fell in Boulder Wednesday) and 00Z Friday 9/13, a total of 9.08” was measured at the during this entire year up to September 8. It put the city within ofcial Boulder site. From 6 PM Monday 9/9 through 6 PM Friday 9/13, striking distance of wettest year on record (29.93”, set in 1995), with the grand total was a whopping 14.71”. only about 2” more needed by December 31 to break that mark. 9 10 Cloud Stories Previous Lecture: Cloud Formation Clouds can tell us many things about our atmospheric environment including – Atmospheric stability – Cloud microphysics, e.g., ice vs liquid – Ice can survive a long time outside of a cloud boundary making the cloud edges diffuse. -

Water in the Atmosphere 97

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Caption goes here © Jonesand can & several Bartlett lines Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTlong FOR as shownSALE here. OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Caption goes here and can several lines long as shown here. Caption goes here and can several lines long as shown here. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 4NOT FOR SALEWater OR DISTRIBUTION in the AtmosphereNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHHAPTTEER OUUTLLININE INTRODUCTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTEVAPORATION: FOR SALE OR THE DISTRIBUTION SOURCE OF ATMOSPHERICNOT WATER FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION MEASURING WATER VAPOR IN THE AIR ■ Mixing Ratio ■ Vapor Pressure © Jones & Bartlett■ Relative Learning, Humidity LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE■ ORDew DISTRIBUTION Point/Frost Point NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CONDENSATION AND DEPOSITION: CLOUD FORMATION ■ Solute and Curvature