Sialorrhea: a Management Challenge NEIL G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diseases of Salivary Glands: Review

ISSN: 1812–1217 Diseases of Salivary Glands: Review Alhan D Al-Moula Department of Dental Basic Science BDS, MSc (Assist Lect) College of Dentistry, University of Mosul اخلﻻضة امخجوًف امفموي تُئة رطبة، حتخوي ػىل طبلة ركِلة من امسائل ثدغى انوؼاب ثغطي امسطوح ادلاخوَة و متﻷ امفراغات تني ااطَة امفموًة و اﻷس نان. انوؼاب سائل مؼلد، ًنذج من امغدد انوؼاتَة، اذلي ًوؼة دورا" ىاما" يف اﶈافظة ػىل سﻻمة امفم. املرىض اذلٍن ؼًاهون من هلص يف اﻷفراز انوؼايب حكون دلهيم مشبلك يف اﻷلك، امخحدث، و امبوع و ًطبحون غرضة مﻷههتاابت يف اﻷغش َة ااطَة و امنخر املندرش يف اﻷس نان. ًوخد ثﻻثة أزواج من امغدد انوؼاتَة ام ئرُسة – امغدة امنكفِة، امغدة حتت امفكِة، و حتت انوساهَة، موضؼيا ٍكون خارج امخجوًف امفموي، يف حمفظة و ميخد هظاهما املنَوي مَفرغ افرازاهتا. وًوخد أًضا" امؼدًد من امغدد انوؼاتَة امطغرية ، انوساهَة، اتحنكِة، ادلىوزيًة، انوساهَة احلنكِة وما كبل امرخوًة، ٍكون موضؼيا مﻷسفل و مضن امغشاء ااطي، غري حماطة مبحفظة مع هجاز كنَوي كطري. افرازات امغدد انوؼاتَة ام ئرُسة مُست مدشاهبة. امغدة امفكِة ثفرز مؼاب مطيل غين ابﻷمِﻻز، وامغدة حتت امفكِة ثنذج مؼاب غين اباط، أما امغدة حتت انوساهَة ثنذج مؼااب" مزخا". ثبؼا" ميذه اﻷخذﻻفات، انوؼاب املوحود يق امفم ٌشار امَو مكزجي. ح كرَة املزجي انوؼايب مُس ثس َطا" واملادة اﻷضافِة اموػة من لك املفرزات انوؼاتَة، اكمؼدًد من امربوثُنات ثنذلل ثرسػة وثوخطق هبدروكس َل اﻷتُذاًت مﻷس نان و سطوح ااطَة امفموًة. ثبدأ أمراض امغدد انوؼاتَة ػادة تخغريات اندرة يف املفرزات و ام كرتَة، وىذه امخغريات ثؤثر اثهواي" من خﻻل جشلك انووحية اجلرثومِة و املوح، اميت تدورىا ثؤدي اىل خنور مذفش َة وأمراض وس َج دامعة. ىذه اﻷمراض ميكن أن ثطبح شدًدة تؼد املؼاجلة امشؼاغَة ﻷن امؼدًد من احلاﻻت اجليازًة )مثل امسكري، امخوَف اهكُيس( ثؤثر يف اجلراين انوؼايب، و ٌش خيك املرض من حفاف يف امفم. -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 7(10), 979-1021

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 7(10), 979-1021 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/9916 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/9916 RESEARCH ARTICLE MINOR ORAL SURGICAL PROCEDURES. Harsha S K., Rani Somani and Shipra Jaidka. 1. Postgraduate Student, Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, Divya Jyoti college of Dental Sciences & Research, Modinagar, UP, India. 2. Professor and Head of the Department, Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences & Research, Modinagar, UP, India. 3. Professor, Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences & Research, Modinagar, UP, India. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History Minor oral surgery includes removal of retained or burried roots, Received: 16 August 2019 broken teeth, wisdom teeth and cysts of the upper and lower jaw. It also Final Accepted: 18 September 2019 includes apical surgery and removal of small soft tissue lesions like Published: October 2019 mucocele, ranula, high labial or lingual frenum etc in the mouth. These procedures are carried out under local anesthesia with or without iv Key words:- Gamba grass, accessions, yield, crude sedation and have relatively short recovery period. protein, mineral contents, Benin. Copy Right, IJAR, 2019,. All rights reserved. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Introduction:- Children are life‟s greatest gifts. The joy, curiosity and energy all wrapped up in tiny humans. This curiosity and lesser motor coordination usually leads to increased incidence of falls in children which leads to traumatic dental injuries. Trauma to the oral region may damage teeth, lips, cheeks, tongue, and temporomandibular joints. These traumatic injuries are the second most important issue in dentistry, after the tooth decay. -

Phenobarbital-Responsive Bilateral Zygomatic Sialadenitis Following an Enterotomy in a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

Research Journal for Veterinary Practitioners Case Report Phenobarbital-Responsive Bilateral Zygomatic Sialadenitis following an Enterotomy in a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel PAOUL S MARTINEZ, RENEE CARTER, LORRIE GASCHEN, KIRK RYAN Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA. Abstract | A 6 year old male castrated Cavalier King Charles Spaniel presented to the Louisiana State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital for a three day history of bilateral acute trismus, exophthalmos, and blindness. These signs developed after an exploratory laparotomy and gastrointestinal foreign body removal was performed. On pre- sentation, the ophthalmic examination revealed bilateral decreased retropulsion, absent bilateral direct and consensual pupillary light responses, bilateral blindness, and a superficial ulcer in right eye. Ocular ultrasound and computed to- mography of the skull were performed and identified a bilateral retrobulbar mass effect originating from the zygomatic salivary glands. Ultrasound guided fine needle aspirate cytology revealed neutrophilic inflammation. Fungal testing and bacterial cultures were performed which were negative for identification of an infectious organism. The patient was placed on a 5-day course of antibiotic therapy and the response was poor. Phenobarbital was added to the treatment regimen. Two days following phenobarbital administration, the exophthalmos and trismus began to resolve. Following phenobarbital therapy, ocular position normalized, trismus completely resolved, and patient returned to normal behav- ior although blindness remained in both eyes. No other neurologic condition occurred. This paper highlights the early use of phenobarbital for the rapid resolution of zygomatic sialadenitis. Keywords | Ultrasound, Sialadenitis, Bilateral exophthalmos, Biomicroscopy, Neutrophilic inflammation Editor | Muhammad Abubakar, National Veterinary Laboratories, Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Pediatric Salivary Gland Pathology Figure 15.9. an 8-Year-Old Girl (A

k Pediatric Salivary Gland Pathology 401 (a) (b) k k (c) (d) Figure 15.9. An 8-year-old girl (a) with left submandibular swelling that had been present for 6 months. Imaging with CT identified an ill-defined mass of the submandibular gland region (b) as well as hydrocephalus (c). Oral examination (d)showed fullness in the left sublingual space. With a differential diagnosis of neurofibroma the patient underwent a debulking of this lesion (e and f). Histopathology identified a plexiform neurofibroma (g), indicative of neurofibromatosis. The patient did well postoperatively as noted at her 2-year visit (h and i). No reaccumulation of the tumor was noted on physical examination. k k 402 Chapter 15 (e) (f) k k (g) (h) (i) Figure 15.9. (Continued) k k Pediatric Salivary Gland Pathology 403 PAROTID TUMORS of which occurred in children. Fifty-seven (71%) of these tumors developed in the parotid gland. In their review of the Salivary Gland Register from 1965–1984 at the University of Hamburg, Seifert, Pleomorphic adenoma accounts for virtually all of et al. (1986) reported on 9883 cases of salivary the benign pediatric neoplasms occurring in the gland pathology, including 3326 neoplasms, 80 parotid gland with the Warthin tumor representing k k (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 15.10. A 9-year-old boy (a) with a mass of the left hard-soft palate junction (b). Incisional biopsy identified low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Imaging with CT (c) showed no bone erosion of the hard palate such that the patient underwent wide local excision of his cancer (d). -

Marsupialisation of Bilateral Ranula in a Buffalo Calf

MOJ Anatomy & Physiology Research Article Open Access Marsupialisation of bilateral ranula in a buffalo calf Abstract Volume 8 Issue 1 - 2021 Diabetes in elderly patients has frequent occurrence of geriatric syndrome. It includes a Kalaiselvan E, Swapan Kumar Maiti, Azam Ranula refers to accumulation of extra-glandular saliva in the floor of the mouth interfering the normal feeding. A male buffalo calf, age of 6 months had bilateral sublingual sialocele Khan, Naveen Kumar Verma, Mohar Singh, (ranula) showing difficulty to masticate and drink water. Bilateral ranula was excised Sharun Khan, Naveen Kumar elliptically to facilitate dynamic fluid/saliva drainage and marsupialisation performed under Division of Surgery, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India anesthesia. Animal showed uneventful recovery without any postoperative complications. Correspondence: Swapan Kumar Maiti, Division of Surgery, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India, Email Received: January 15, 2021 | Published: Febrauary 15, 2021 Introduction saliva into the mouth (Figure 1–4). The owner was advised to clean the oral cavity with povidone iodine for 7 days. Postoperatively, Ranula or sublingual sialocele refers to a collection of extra- antibiotic, analgesic and fluid therapy was administered for 5 days. glandular and extra-ductal saliva in the floor of the mouth originating On 10thpost-operative day animal showed normal feeding habit and from the sublingual salivary gland. It -

Statistical Analysis Plan

Cover Page for Statistical Analysis Plan Sponsor name: Novo Nordisk A/S NCT number NCT03061214 Sponsor trial ID: NN9535-4114 Official title of study: SUSTAINTM CHINA - Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Document date: 22 August 2019 Semaglutide s.c (Ozempic®) Date: 22 August 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL Clinical Trial Report Status: Final Appendix 16.1.9 16.1.9 Documentation of statistical methods List of contents Statistical analysis plan...................................................................................................................... /LQN Statistical documentation................................................................................................................... /LQN Redacted VWDWLVWLFDODQDO\VLVSODQ Includes redaction of personal identifiable information only. Statistical Analysis Plan Date: 28 May 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL UTN:U1111-1149-0432 Status: Final EudraCT No.:NA Page: 1 of 30 Statistical Analysis Plan Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Author Biostatistics Semaglutide s.c. This confidential document is the property of Novo Nordisk. No unpublished information contained herein may be disclosed without prior written approval from Novo Nordisk. Access to this document must be restricted to relevant parties.This -

Sialocele with Sialolithiasis in a Beagle Dog

J Vet Clin 26(4) : 371-375 (2009) Sialocele with Sialolithiasis in a Beagle Dog Young-Hang Kwon, Soo-Ji Lim, Jin-Hwa Chang, Ji-Young An, Se-Joon Ahn, Seong-Mok Jeong, Seong-Jun Park, Sung-Whan Cho, Ho-Jung Choi and Young-Won Lee1 College of Veterinary Medicine · Research Institute of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 305-764, Korea (Accepted : August 19, 2009) Abstract : A three-year-old Beagle dog was presented with the neck mass. Mass was located at ventral part of the mandible. The dog showed excessive drooling. Sialocele with calculi was evaluated based on physical exam, radiographs, ultrasonography, and computed tomography. Salivary gland resection was performed. Histopathological examination confirmed sialoadenitis concurred with sialocele. Key words : Sialocele, radiograph, ultrasonography, sialolithiasis, sialoadenitis. Introduction Hyperechoic materials accompanying acoustic shadow also were detected on the dependent portion of cavitary lesion Sialocele, or salivary mucocele is an accumulation of saliva (Fig 2-B). The hyperechoic objects were suspected as intrag- in subcutaneous tissue due to tear in a salivary gland or duct landular sialoliths, which were shown on the radiographs. No and often occurs in dogs (7). Sialolithiasis is defined as the evidence of vascularization was detected. FNA was per- formation of calcified secretions in a salivary gland or duct, formed guided by ultrasound. Aspirated samples of the and is infrequent as compared with salivary mucocele (23). swelling lesion showed viscous, lucent, and hazy contents. Painless swelling of the neck and oral cavity is the most RBCs and inflammatory cells were detected on the micro- common clinical signs associated with salivary gland abnor- scopic study. -

Sialocele/Ranula

VETERINARY PROFESSIONAL SERIES SPIT RELOCATED: When a salivary duct is ruptured and pockets of saliva start growing. Synopsis The salivary system includes a gland, a duct and an orifice in the mouth. Saliva is generated in the gland, travels down the duct and exits nicely in the mouth in response to stimuli. When a gland or duct is injured, either by trauma, inflammation, obstruction or tumor, saliva will leak into the surrounding tissues where it is a foreign substance. The body will respond with inflammation (red and white blood cells, etc.) The proteinaceous nature of saliva makes it very slow to be removed, but the fluid nature will be resorbed over time. The result is a very inspissated, thick, red/cloudy viscous fluid hanging out in an odd location. The most common presentations are: 1) mandibular salivary gland/duct injury with resultant saliva accumulation in the ventolateral neck region (sialocele); 2) sublingual salivary gland/duct injury with resultant saliva accumulation laterally under the tongue (ranula). Or a combo platter of both. (I use this terminology to help distinguish things during communications about this condition.) Treatment is not an emergency; the condition is rarely troublesome to the pet. It is disturbing to owners though. Draining the pocket of salivary fluid may resolve the issue ONLY if the original duct/gland leak has stopped. Worth trying; nothing is lost except time. It is very uncommon for a sialocele or ranula to be truly infected; sialadenitis and migrating foreign bodies in salivary ducts look very different—pain, inflammation, pus. Treatment for any presentation involving a cervical component is to remove the mandibular/sublingual gland and duct and drain the extravasated saliva. -

Underwritten By

Underwritten by: National Casualty Company Home Office: One Nationwide Plaza • Columbus, Ohio 43215 Administrative Office: 8877 North Gainey Center Drive • Scottsdale, Arizona 85258 1-800-423-7675 • A Stock Company DIRECT ALL INQUIRES AND CLAIMS TO: DVM Insurance Agency 1800 E. Imperial Highway, Suite 145 • Brea, CA 92821 • 1-800-540-2016 • 1-714-989-0555 MAJOR MEDICAL PLAN COVERAGE FORM 1. INSURING AGREEMENT We will provide the benefits listed in the Major Medical Plan Benefit Schedule in return for your payment of premium when due and compliance with all provisions of this policy. We will pay covered veterinary expenses that you incur during the policy term for diagnosis or treatment of your pet’s condition. Benefit payments are subject to all exclusions, limitations, and conditions of this insurance policy. 2. DEFINITIONS We define terms and phrases in your policy. We identify these terms with bold typeface. Any veterinary terms or phrases not defined in this policy will be interpreted as defined in the most recent edition of Blood D.C., Studdert V.P., Gay C.C, Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary. London, UK: W.B. Saunders. A. Chemotherapy means treatment through chemicals primarily designed to stop the progression of cancer. B. Chronic condition means a condition that can be treated or managed, but not cured. C. Condition means an illness or injury that your pet contracts or incurs. D. Congenital anomaly or disorder means a condition that is present from birth, whether inherited or caused by the environment, which may cause or otherwise contribute to illness or disease. E. Covered veterinary expenses means expenses for reasonable and necessary veterinary services that are eligible for payment under the Major Medical Plan. -

Management of a Parotid Sialocelein a Young Patient: Case Report and Literature Review

www.scielo.br/jaos Management of a parotid sialocelein a young patient: case report and literature review Melissa Rodrigues de ARAUJO1, Bruna Stuchi CENTURION2, Danielle Frota de ALBUQUERQUE3, Luiz Henrique MARCHESANO4, José Humberto DAMANTE5 1- DDS, MSc, PhD. Department of Stomatology, Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. 2- DDS, Department of Stomatology, Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. 3- DDS, MSc. Department of Stomatology, Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. 4- MSc, PhD. Clinical Analysis Laboratory, Craniofacial Anomalies Rehabilitation Hospital, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. 5- DDS, MSc, PhD, Full Professor. Department of Stomatology, Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo, Bauru, SP, Brazil. Corresponding address: Melissa Rodrigues de Araujo - Rua Pedro Romildo Dall Stella, 100 - casa 5 - 82.115-470 - Phone: 41 3023 3357 or 8417 0800 - [email protected] Received: March 13, 2009 - Modification: September 5, 2009 - Accepted: October 9, 2009 ABSTRACT ialocele is a subcutaneous cavity containing saliva, caused by trauma or infection in Sthe parotid gland parenchyma, laceration of the parotid duct or ductal stenosis with subsequent dilatation. It is characterized by an asymptomatic soft and mobile swelling on the parotid region. Imaging studies are useful and help establishing the diagnosis, such as sialography, ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. This paper describes a recurrent case of a parotid sialocele in a young female patient. She presented a 6 cm x 5 cm swelling on the left parotid region. The ultrasonographic scan of the area revealed a hypoechoic ovoid well defined image suggesting a cyst. -

Section III the African Perspective

Section III The African Perspective 12 Aesthetic, Ethnic, and Cultural Considerations and Current Cosmetic Trends in the African Descent Population Monte Oyd Harris “To be sure of one’s self, to be counted for one’s While the field of aesthetics has largely been dominated self, is to experience aliveness in its most by European canons, an expanding global awareness has exciting dimension.” –Howard Thurman emerged that allows space for new perceptions of beauty and being “African” in the world today. For the purposes of this chapter, African refers to peo- 12.1 Location is Everything ple of African descent whose lives have been by influenced by some or all of the following: the transatlantic slave This is most likely the first book chapter on the topic of facial trade, European colonialism, Western imperialism, racism, plastic surgery written from a location of African centered- and global migration. The notion of African centeredness ness. In researching perspectives on cosmetic trends in the is rooted in Afrocentric philosophy, notably championed African descent population, I found very little in the sur- by African American studies scholar Molefi Kente Asante. gery literature that truly originated from a place of African Asante asserts, “Afrocentricity is about location precisely centrality. Even in the seminal textbook Ethnic Consider- because African people living in Western society have ations in Facial Aesthetic Surgery, edited by W. Earle Matory, largely been operating from the fringes of the Eurocentric the premise of African beauty was largely determined experience. Whether it is a matter of economics, history, through comparison to neoclassical aesthetic proportions based upon European standards.1 For most physicians, Afri- can beauty has been beholden to an objective ability to see, to measure, and to compare with a presumed Eurocentric ideal.2–5 African centrality, however, prioritizes a view that there is much more to beauty than meets the eye. -

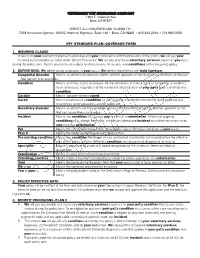

Vpi® Standard Plan–Coverage Form 1. Insuring

VETERINARY PET INSURANCE COMPANY 1800 E. Imperial Hwy Brea, CA 92821 DIRECT ALL INQUIRIES AND CLAIMS TO: DVM Insurance Agency: 1800 E. Imperial Highway, Suite 145 • Brea, CA 92821 • 800-540-2016 • 714-989-0555 VPI® STANDARD PLAN–COVERAGE FORM 1. INSURING CLAUSE In return for your payment of premium when due and your compliance with the provisions of this policy, we will pay your incurred policy benefits as listed under “Benefit Provisions.” We will pay only those veterinary services expenses you incur during the policy term. Benefit payments are subject to all exclusions, limitations, and conditions of this insurance policy. 2. DEFINITIONS: We define words or phrases in your policy. We identify these terms with bold typeface. Congenital disorder Means an abnormality present at birth, whether apparent or not, that can cause illness or disease. See Section 8 for examples. Condition Means an illness, injury, or disease. All manifestations of clinical signs or symptoms of an illness, injury, or disease, regardless of the number of affected areas of your pet's body, constitute one condition. Curable Means capable of being cured. Cured Means resolution of a condition so that ongoing or intermittent treatment is not required and recurrences or complications are not expected. Hereditary disorder Means an abnormality transmitted by gene(s) from parent to offspring, whether apparent or not, that can cause illness or disease. Incident Means any condition that causes you to consult a veterinarian. Chronic or ongoing conditions, e.g. allergic dermatitis, will be considered one incident no matter how many times you consult a veterinarian.