Monuments of Our Modern Past Messages from Mid-Century AIA Sierra Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

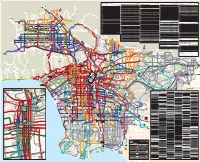

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

De Wain Valentine

DE WAIN VALENTINE Born in 1936 in Fort Collins, CO, US Lives and Works in Los Angeles, CA, US SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Almine Rech Gallery, New York, US (UPcoming) 2017 Ruhrtriennale 2017, Ruhr, Germany 2015 Almine Rech Gallery, London, UK David Zwirner, New York, NY, US 2014 Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 2012 "DeWain Valentine : Human Scale," GMOA, Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA, US 2011 "From Start To Finish: DeWain Valentine’s Gray Column (1975-76)," Presented By The Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Center / J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, US 2010 Ace Gallery Beverly Hills, Beverly Hills, CA, US 2009 Museum Of Design Art & Architecture. SPf: AGallery, Culver City, CA, US 2008 Scott White ContemPorary Art, San Diego, CA, US 2005 Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA, US 1993 Galerie Simonne Stern, New Orleans, LA, US 1991 Works Gallery, Long Beach, CA, US 1985 Honolulu Academy Of Arts, ContemPorary Arts Center, Honolulu, HI, US 1984 Thomas Babeor Gallery, La Jolla, CA, US 1983 Madison Art Center, Madison, WI, US 1982 Thomas Babeor Gallery, La Jolla, CA, US Missouri Botanical Garden, La Jolla, CA, US Laumeier Gallery, Laumeier International SculPture Park, St. Louis, MO, US 1981 Projects Studio One, Institute For Art And Urban Resources, New York, NY, US 1979 Los Angeles County Museum Of Art, Los Angeles, CA, US Fine Arts Gallery, University Of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, US 1975 La Jolla Museum Of Contemporary Art, La Jolla, CA, US Long Beach Museum Of Art, Long Beach, CA, US Art Gallery, California State University Northridge, -

Figueroa Tower 660 S

FIGUEROA TOWER 660 S. FIGUEROA STREET LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA UNMATCHED DOWNTOWN RETAIL VISIBILITY RETAIL RESTAURANT SPACE FOR LEASE FLAGSHIP RESTAURANT SPACE AVAILABLE For more information, please contact: Gabe Kadosh Vice President Colliers International License No. 01487669 +1 213 861 3386 [email protected] UNMATCHED DOWNTOWN RETAIL VISIBILITY 660 S. FIGUEROA STREET A postmodern mixed-use property bordered by Seventh and Figueroa streets The building consists of 12,000 square feet of ground-floor retail space—below a 283,000 SF Class A Office —including significant frontage feet of coveted frontage on major thoroughfare Figueroa. Figueroa Tower’s beautiful exterior combines the characteristics of traditional French architecture with the sleek verticality of a modern high-rise. These attributes, together with its location at the center of the Figueroa Financial Corridor, offer an aesthetic experience unlike any retail destination in all of Los Angeles. This corridor was solidified abuilding in California, the Wilshire Grand Center, opened directly across the street. This prestigious location boasts a high pedestrian volume and an unparalleled daily traffic count of 30,000. Such volume is thanks in part to being just steps away from retail supercenter FIGat7th, as well as sitting immediately above Seventh Street Metro Center Station, the busiest subway station in Los Angeles by far. Figueroa Tower also benefits from ongoing improvements to Downtown Los Angeles, which is currently undergoing its largest construction boom since the 1920s. In the last decade alone, 42 developments of at least 50,000 square feet have been built and 37 projects are under construction. This renaissance of development has reignited the once-sleepy downtown area into a sprawling metropolis of urban residential lofts and diverse retail destinations. -

Administrative Dissolution

ENTITY ID NAME C0697583 "CHURCH OF THE BROTHERHOOD" C0682834 "CLUB BENEFICO SOCIAL PUERTORRIQUENO DE OAKLAND" C0942639 10831 FRUITLAND C0700987 111 SOUTH ORANGE GROVE INC C0948235 12451 PACIFIC AVENUE CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION C0535004 1312 Z, INC. C0953809 1437-39 PRINCETON HOME OWNERS' ASSOCIATION C0502121 16TH ANNUAL NATIONAL NISEI CONVENTION VETERANS OF FOREIGN W- C0542927 3 DISTRICT-CDF EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION C0812129 3 R SCHOOLS - SAN LEANDRO, INC. C0612924 3358 KERN COUNTY PROPERTY OWNERS ASSOCIATION INC C0454484 40 PLUS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA C0288712 44 CLUB, INC. C0864792 4646 WILLIS HOMEOWNERS ASSOCIATION, INC. C0542192 559, INC. C0559640 57TH STREET NEIGHBORHOOD YOUTH IMPROVEMENT PROJECT, INC. C0873251 6305 VISTA DEL MAR OWNERS ASSOCIATION C0794678 6610 SPRINGPARK OWNERS ASSOCIATION C0698482 77TH BUSINESSMEN'S BOOSTER ASSOCIATION INC. C0289348 789 BUILDING INC. C0904419 91ST. DIVISION POST NO. 1591, VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED S C0686053 A BLACK BOX THEATRE INC C0813882 A CENTRAL PLACE C0893890 A CORPORATION FOR THE ENVIRONMENT INCORPORATED C0541775 A SEGMENT OF THE BRIDE OF CHRIST C0749468 A UNITED MINISTRY CORPORATION C0606660 ABC FOR FOOTBALL, INC. C0817710 ABUNDANT LIFE CENTER C0891524 ACADEMIA ORIENTALIS C0736615 ACADEMIA QUINTO SOL C0486088 ACADEMIC RESOURCES C0434577 ACADEMY OF MASTER WINE GROWERS C0689600 ACADEMY OF THE BROTHERHOOD ENTITY ID NAME C0332867 ACCORDION FEDERATION OF NORTH AMERICA, INC. C0729673 ACCOUNTANTS FOR THE PUBLIC INTEREST C0821413 ACTION FOR ANIMALS C0730535 ACTIVE RETIRED ALTADENANS C0538260 -

A Rccaarchitecture California the Journal of the American Institute Of

architecture california the journal of the american institute of architects california council a r cCA aiacc design awards issue 04.3 photo finish ❉ Silent Archives ❉ AIACC Member Photographs ❉ The Subject is Architecture arcCA 0 4 . 3 aiacc design a wards issue p h o t o f i n i s h Co n t e n t Tracking the Awards 8 Value of the 25 Year Award 10 ❉ Eric Naslund, FAIA Silent Archives: 14 In the Blind Spot of Modernism ❉ Pierluigi Serraino, Assoc. AIA AIACC Member Photographs 18 ❉ AIACC membership The Subject is Architecture 30 ❉ Ruth Keffer AIACC 2004 AWARDS 45 Maybeck Award: 48 Daniel Solomon, FAIA Firm of the Year Award: 52 Marmol Radziner and Associates Lifetime Achievement 56 Award: Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by John Parman Lifetime Achievement 60 Award: Daniel Dworsky, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by Christel Bivens Kanda Design Awards 64 Reflections on the Awards 85 Jury: Eric Naslund, FAIA, and Hugh Hardy, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by Kenneth Caldwell Savings By Design A w a r d s 88 Co m m e n t 03 Co n t r i b u t o r s 05 C r e d i t s 9 9 Co d a 1 0 0 1 arcCA 0 4 . 3 Editor Tim Culvahouse, AIA a r c C A is dedicated to providing a forum for the exchange of ideas among mem- bers, other architects and related disciplines on issues affecting California archi- Editorial Board Carol Shen, FAIA, Chair tecture. a r c C A is published quarterly and distributed to AIACC members as part of their membership dues. -

2016 Skechers Performance Los Angeles Marathon Media Guide

2016 Skechers Performance Los Angeles Marathon Media Guide Important Media Information 3 Race Week Schedule 4 About the Race 7 8 Legacy Runners The Course 10 History 25 Logistics 32 On Course Entertainment 37 Media Coverage 43 LA BIG 5K 44 Professional Field 46 Race Records 52 Charities 67 Partners & Sponsors 72 Marathon Staff 78 2017 Skechers Performance Los Angeles Marathon Media Guide Media Contacts Carsten Preisz Jolene Abbott VP, Brand Strategy and Marketing Executive Director, Public Relations Conqur Endurance Group Skechers Performance 805.218.7612 310.318.3100 [email protected] [email protected] Molly Biddiscombe Kerry Hendry Account Supervisor Vice President Ketchum Sports & Entertainment Ketchum Sports & Entertainment 860-539-2492 404-275-0090 [email protected] [email protected] Finish Line Media Center Media Credential Pickup Fairmont Hotel LA Convention Center Wedgewood Ballroom West Hall, Room 510 101 Wilshire Blvd 1201 S. Figueroa Street Santa Monica, CA Los Angeles, CA 90015 310-899-4136 Friday, March 17: 10:30 am – 5 pm Saturday, March 18: 9 am – 2 pm Press Conference Schedule Fairmont Hotel Friday, Wedgewood Ballroom 8:00 am Sunday 6:00 am to 3:00 pm ‘Meet the Elites’ Event, Griffith Park Top athletes, Conqur CEO Tracey Russell Social 11:00 am Pages Website: www.lamarathon.com Pre-race Press Conference, LA Convention Center, West Hall, Room510 www.goconqur.com Top athletes Facebook: facebook.com/LAmarathon Instagram: @lamarathon Sunday, Twitter: @lamarathon 10:00 am Snapchat: @lamarathon -

Eames House Case Study #8 : a Precedent Study Lauren Martin Table of Contents

EAMES HOUSE CASE STUDY #8 : A PRECEDENT STUDY LAUREN MARTIN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TITLE PAGE 2. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3. WHO? 4. WHERE & WHY? 5. DESIGN 6. PROPERTY DETAILS & SPECS 7.PLANS & SECTIONS 8. ELEVATIONS 9. PROGRAM 10. EXPERIENCE 11. SUSTAINABILITY 12. BIBLOGRAPHY WHO? C “EVENUTALLY, EVERYTHING CONNECTS” The Eameses are best known for their H -CHARLES EAMES groundbreaking contributions to architecture, furniture design, industrial A design and manufacturing, and the photographic arts. R “THE ARCHITECT & THE PAINTER” L Charles Eames was born in 1907, in St. Louis Missouri. He attended school there, developing an interest in engineering and architecture. By 1930 he E had opened his own architectural office. Later, he became the head of the design department at Cranbrook Academy. Ray Eames was born in 1912 in Sacramento, California. She studied painting with Hans Hofmann in New York before moving on to Cranbrook Academy where she met and assisted S Charles and Eero Saarinen in preparing designs for the MOMA’s Organic Furniture Competition. Married in 1941, they continued furniture design and later architectural design. & R A Y WHERE? WHY? In 1949, Charles and Ray designed and built their own home in Pacific Palisades, California, as part of the Case Study House Program sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine. Located in the Pacific Palisades area Their design and innovative use of materials made the house a mecca for architects and designers from both near and far. Today, it is of Los Angeles, California. The Eames considered one of the most important post-war residences anywhere in House is composed of a residence and the world. -

The Los Angeles Public Landscapes of Ralph Cornell Los Angeles, CA

What’s Out There® The Los Angeles Public Landscapes of Ralph Cornell Los Angeles, CA Welcome to What’s Out There Los Angeles – The What’s Out There Los Angeles – The Public Landscapes Public Landscapes of Ralph Cornell, organized by of Ralph Cornell was accompanied by the development The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) with of an exhibit of his drawings, photographs, and personal support from local and national partners. effects. On view at the UCLA Charles E. Young Research The narratives and photographs in this guidebook describe Library, the installation was curated by Steven Keylon, Kelly thirteen sites, just a sampling of Cornell’s built legacy. The Comras, Sam Watters, and Genie Guerrard and introduced sites were featured in What’s Out There Weekend Los Angeles, with a lecture on Cornell’s legacy given by Brain Tichenor, which offered free, expert-led tours in November 2014. This professor of USC’s School of Architecture. The tours, What’s Out There Weekend—the eleventh in an on-going series exhibit, and lecture were attended by capacity crowds, of regionally-focused tour events increasing the public visibility demonstrating the overwhelming public interest to discover Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden, photo by Matthew Traucht of designed landscapes, their designers, and their patrons—is more about this significant shaper of Southern California. TCLF’s first focused on the work of a single designer. This guidebook and the What’s are Out There Weekends In researching the extant public landscapes of Ralph Cornell dovetail with the Web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s we came to understand why he is called “the Olmsted most comprehensive, searchable database of our shared of Los Angeles.” A prolific designer, author, mentor, and landscape legacy. -

Snapchat to Become Sole Tenant of Santa Monica Place

FORCEFUL LITIGATORS WITTENBERG LAW CREATIVE BUSINESS, INVESTMENT & TRIAL ATTORNEYS DEALMAKERS 310-295-2010 | www.WittenbergLawyers.com MONDAY APRIL FOOLS’ 04.01.19 EDITION Volume 18 Issue 119 @smdailypress @smdailypress Santa Monica Daily Press smdp.com Chez Jay to be replaced with boutique Cheesecake Snapchat to become sole Factory-branded ‘Chez Cayke’ tenant of Santa Monica Place Artist rendering DECOR: A corporate restaurant will take over the local institution. BY SPIN DOCTOR that it will be closing in lieu of a “Chez Cayke”, an experimental In a stunning show of Santa boutique restaurant owned and Monica’s cultural erosion operated by the Cheesecake continuing, another legendary Factory. This new boutique will be local haunt will close and be an upscale version of Cheesecake replaced by a factory famous for Factory’s chain restaurants. its gluttonous foods. Chez Jay announced yesterday SEE CHEZ CAYKE PAGE 3 Artist rendering SNAPMALL: The new tenants of the Downtown mall plan to install augmented reality filters for employees. District elections trigger deathmatch rules to BY WHEELS DEALS in West Los Angeles earlier this year. The project converted an entire shopping mall into decide new Mayor Following the trend established when Google a 584,000-square-foot creative office campus. took over a Los Angeles Mall, Snapchat has The venture was a partnership between several BY POWER LYFTER mayorship of the city was set to be announced plans to become the sole tenant at companies including Makemoney who also own up for grabs via a normal election. Santa Monica Place. Santa Monica Place. In a jaw-dropping move this past However, after a short back and The company will keep the movie theater, food Faced with continued vacancies in the mall, week, the City Council agreed to forth at last night’s last-minute court and Disney Store but those facilities will be Makemoney has been increasingly moving away engage in a winner-take-all death council meeting, City Council for the exclusive use of their employees. -

Digital Photo Proof Pages

F cover 42 summer14:ToC 4/9/14 12:30 PM Page 1 john entenza house 12 texas & florida updates 34, 60 the past perfected 46 SUMMER 2014 $6.95 us/can On sale until August 31, 2014 AtomicRanch 42 3/19/14 6:21 PM Page 1 AUDREY DINING made to order made in america made to last KYOTO DINING SOHO BEDROOM FUSION END TABLE Available near you at: California Benicia - Ironhorse Home Furnishings (707) 747-1383, Capitola - Hannah’s Home Furnishings (831) 462-3270, Long Beach - Metropolitan Living (562) 733-4030, Monterey - Europa Designs (831) 372-5044, San Diego - Lawrance Contemporary Furniture (800) 598-4605, San Francisco - Mscape (415) 543-1771, Santa Barbara - Michael Kate Interiors (805) 963-1411, Studio City - Bedfellows (818) 985-0500, Torrance - Contemporary Lifestyles (310) 214-2600, Thousand Oakes - PTS (805) 496-4804, Colorado Fort Collins - Forma Furniture (970) 204-9700, Connecticut New Haven - Fairhaven (203) 776-3099, District of Columbia Washington - Urban Essentials (202) 299-0640, Florida Sarasota - Copenhagen Imports (941) 923-2569, Georgia Atlanta - Direct Furniture (404) 477-0038, Illinois Chicago - Eurofurniture (800) 243-1955, Indiana Indianapolis - Houseworks (317) 578-7000, Iowa Cedar Falls - Home Interiors (319) 266-1501, Manitoba Winnipeg - Bella Moda (204) 783-4000, Maryland Columbia - Indoor Furniture (410) 381-7577, Massachusetts Acton - Circle Furniture (978) 263-7268, Boston - Circle Furniture (617) 778-0887, Cambridge - Circle Furniture (617) 876-3988, Danvers - Circle Furniture (978) 777-2690, Framingham - Circle -

Eames House: a Precedent Study

EAMES HOUSE: A PRECEDENT STUDY Lea Santano & Lauren Martin Table Of Contents LOCATED in the Pacific Palisades General Information THE EAMESES are best known for area of Los Angeles, California. The Eames their groundbreaking contributions to House is composed of a residence and architecture, furniture design, industrial studio overlooking the Pacific Ocean. design and manufacturing, and the photographic arts. “The Architect & The Painter” THE DESIGN is one of the few architectural works DESIGNED by Charles and Ray Eames, the original attributed to Charles Eames, and embodies many of design of the house was proposed by Charles and Ray the distinguishing characteristics and ideals of postwar as part of the famous Case Study House program for Modernism in the United States. John Entenza’s Arts & Architecture magazine. DATES OF SIGNIFIGANCE for THE EAMES HOUSE THE IDEA of a Case Study house was the Eames House coincide with the has been regarded as one of to hypothesize a modern household, residency of its designers, extending the most significant elaborate its functional requirements, have from 1949 until 1988. experiments in American an esteemed architect develop a design Other dates include 1978. domestic architecture. that met those requirements using modern materials and construction processes. SITE INFORMATION AND SPECIFICS PLANS/AXO/SECTIONS The Studio Bay Above is a picture of the original design of the Eames House. It was later adjusted to fit in with the The Resdiential Bay environment surrounding the property. The Eameses wanted to build something that worked with the site, not just something placed on top of it. This axonometric drawing breaks down the Case Study House concept and construction #8 of the Eames House.