Farming with Crops and Rocks to Address Global Climate, Food and Soil Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Default Emissions from Biofuels

Definition of input data to assess GHG default emissions from biofuels in EU legislation Version 1c - July 2017 Edwards, R. Padella, M. Giuntoli, J. Koeble, R. O’Connell, A. Bulgheroni, C. Marelli, L. 2017 EUR 28349 EN This publication is a Science for Policy report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of this publication. JRC Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC104483 EUR 28349 EN PDF ISBN 978-92-79-64617-1 ISSN 1831-9424 doi:10.2790/658143 Print ISBN 978-92-79-64616-4 ISSN 1018-5593 doi:10.2790/22354 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 © European Union, 2017 The reuse of the document is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The European Commission shall not be held liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. How to cite this report: Edwards, R., Padella, M., Giuntoli, J., Koeble, R., O’Connell, A., Bulgheroni, C., Marelli, L., Definition of input data to assess GHG default emissions from biofuels in EU legislation, Version 1c – July 2017 , EUR28349 EN, doi: 10.2790/658143 All images © European Union 2017 Title Definition of input data to assess GHG default emissions from biofuels in EU legislation, Version 1c – July 2017 Abstract The Renewable Energy Directive (RED) (2009/28/EC) and the Fuel Quality Directive (FQD) (2009/30/EC), amended in 2015 by Directive (EU) 2015/1513 (so called ‘ILUC Directive’), fix a minimum requirement for greenhouse gas (GHG) savings for biofuels and bioliquids for the period until 2020, and set the rules for calculating the greenhouse impact of biofuels, bioliquids and their fossil fuels comparators. -

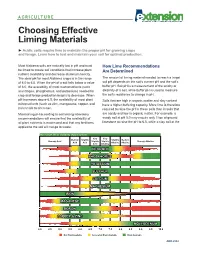

Choosing Effective Liming Materials ► Acidic Soils Require Lime to Maintain the Proper Ph for Growing Crops and Forage

AGRICULTURE Choosing Effective Liming Materials ► Acidic soils require lime to maintain the proper pH for growing crops and forage. Learn how to test and maintain your soil for optimal production. Most Alabama soils are naturally low in pH and must How Lime Recommendations be limed to create soil conditions that increase plant Are Determined nutrient availability and decrease aluminum toxicity. The ideal pH for most Alabama crops is in the range The amount of liming material needed to reach a target of 6.0 to 6.5. When the pH of a soil falls below a value soil pH depends on the soil’s current pH and the soil’s of 6.0, the availability of most macronutrients (such buffer pH. Soil pH is a measurement of the acidity or as nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium) needed for alkalinity of a soil, while buffer pH is used to measure crop and forage production begins to decrease. When the soil’s resistance to change in pH. pH increases above 6.5, the availability of most plant Soils that are high in organic matter and clay content micronutrients (such as zinc, manganese, copper, and have a higher buffering capacity. More lime is therefore iron) tends to decrease. required to raise the pH in these soils than in soils that Maintaining pH according to soil testing laboratory are sandy and low in organic matter. For example, a recommendations will ensure that the availability of sandy soil at pH 5.0 may require only 1 ton of ground all plant nutrients is maximized and that any fertilizers limestone to raise the pH to 6.5, while a clay soil at the applied to the soil will not go to waste. -

Guadalupian, Middle Permian) Mass Extinction in NW Pangea (Borup Fiord, Arctic Canada): a Global Crisis Driven by Volcanism and Anoxia

The Capitanian (Guadalupian, Middle Permian) mass extinction in NW Pangea (Borup Fiord, Arctic Canada): A global crisis driven by volcanism and anoxia David P.G. Bond1†, Paul B. Wignall2, and Stephen E. Grasby3,4 1Department of Geography, Geology and Environment, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK 2School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK 3Geological Survey of Canada, 3303 33rd Street N.W., Calgary, Alberta, T2L 2A7, Canada 4Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive N.W., Calgary Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada ABSTRACT ing gun of eruptions in the distant Emeishan 2009; Wignall et al., 2009a, 2009b; Bond et al., large igneous province, which drove high- 2010a, 2010b), making this a mid-Capitanian Until recently, the biotic crisis that oc- latitude anoxia via global warming. Although crisis of short duration, fulfilling the second cri- curred within the Capitanian Stage (Middle the global Capitanian extinction might have terion. Several other marine groups were badly Permian, ca. 262 Ma) was known only from had different regional mechanisms, like the affected in equatorial eastern Tethys Ocean, in- equatorial (Tethyan) latitudes, and its global more famous extinction at the end of the cluding corals, bryozoans, and giant alatocon- extent was poorly resolved. The discovery of Permian, each had its roots in large igneous chid bivalves (e.g., Wang and Sugiyama, 2000; a Boreal Capitanian crisis in Spitsbergen, province volcanism. Weidlich, 2002; Bond et al., 2010a; Chen et al., with losses of similar magnitude to those in 2018). In contrast, pelagic elements of the fauna low latitudes, indicated that the event was INTRODUCTION (ammonoids and conodonts) suffered a later, geographically widespread, but further non- ecologically distinct, extinction crisis in the ear- Tethyan records are needed to confirm this as The Capitanian (Guadalupian Series, Middle liest Lopingian (Huang et al., 2019). -

Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality E.L

University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment ID-163 Cooperative Extension Service Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality E.L. Ritchey, L.W. Murdock, D. Ditsch, and J.M. McGrath, Plant and Soil Sciences; F.J. Sikora, Division of Regulatory Services oil acidity is one of the most important soil factors affect- Figure 1. Liming acid soils increases exchangeable Ca and Mg. Sing crop growth and ultimately, yield and profitability. It is determined by measuring the soil pH, which is a measure Acid Soil Limed Soil Ca2+ H+ H+ Ca2+ Ca2+ of the amount of hydrogen ions in the soil solution. As soil Lime Applied H+ H+ H+ H+ Ca2+ acidity increases, the soil pH decreases. Soils tend to be + + + 2+ + naturally acidic in areas where rainfall is sufficient to cause H H H Mg H substantial leaching of basic ions (such as calcium and mag- nesium), which are replaced by hydrogen ions. Most soils in Kentucky are naturally acidic because of our abundant rainfall. Nitrogen fertilization can also contribute to soil acid- The majority of the hydrogen ions are actually held on ity as the nitrification of ammonium increases the hydrogen cation exchange sites. To effectively neutralize soil acidity, ion concentration in the soil through the following reaction: hydrogen ions must be removed from both the soil solution and the exchange sites. While soil pH only measures the solu- + - - + NH4 + 2O2 --> NO3 = H2O + 2H tion hydrogen, the buffer pH is an indication of exchangeable acidity and how much ag lime is actually needed. It is possible Periodically, agricultural limestone (ag lime) is needed to for two soils to have the same water pH but different lime neutralize soil acidity and maintain crop productivity. -

Wrangellia Flood Basalts in Alaska, Yukon, and British Columbia: Exploring the Growth and Magmatic History of a Late Triassic Oceanic Plateau

WRANGELLIA FLOOD BASALTS IN ALASKA, YUKON, AND BRITISH COLUMBIA: EXPLORING THE GROWTH AND MAGMATIC HISTORY OF A LATE TRIASSIC OCEANIC PLATEAU By ANDREW R. GREENE A THESIS SUBMITTED iN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geological Sciences) UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2008 ©Andrew R. Greene, 2008 ABSTRACT The Wrangellia flood basalts are parts of an oceanic plateau that formed in the eastern Panthalassic Ocean (ca. 230-225 Ma). The volcanic stratigraphy presently extends >2300 km in British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska. The field relationships, age, and geochemistry have been examined to provide constraints on the construction of oceanic plateaus, duration of volcanism, source of magmas, and the conditions of melting and magmatic evolution for the volcanic stratigraphy. Wrangellia basalts on Vancouver Island (Karmutsen Formation) form an emergent sequence consisting of basal sills, submarine flows (>3 km), pillow breccia and hyaloclastite (<1 1cm), and subaerial flows (>1.5 km). Karmutsen stratigraphy overlies Devonian to Permian volcanic arc (—‘380-355 Ma) and sedimentary sequences and is overlain by Late Triassic limestone. The Karmutsen basalts are predominantly homogeneous tholeiitic basalt (6-8 wt% MgO); however, the submarine part of the stratigraphy, on northern Vancouver Island, contains picritic pillow basalts (9-20 wt% MgO). Both lava groups have overlapping initial and ENd, indicating a common, ocean island basalt (OIB)-type Pacific mantle source similar to the source of basalts from the Ontong Java and Caribbean Plateaus. The major-element chemistry of picrites indicates extensive melting (23 -27%) of anomalously hot mantle (‘—1500°C), which is consistent with an origin from a mantle plume head. -

Large Igneous Provinces and Mass Extinctions: an Update

Downloaded from specialpapers.gsapubs.org on April 29, 2015 OLD G The Geological Society of America Special Paper 505 2014 OPEN ACCESS Large igneous provinces and mass extinctions: An update David P.G. Bond* Department of Geography, Environment and Earth Science, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, UK, and Norwegian Polar Institute, Fram Centre, 9296 Tromsø, Norway Paul B. Wignall School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK ABSTRACT The temporal link between mass extinctions and large igneous provinces is well known. Here, we examine this link by focusing on the potential climatic effects of large igneous province eruptions during several extinction crises that show the best correlation with mass volcanism: the Frasnian-Famennian (Late Devonian), Capi- tanian (Middle Permian), end-Permian, end-Triassic, and Toarcian (Early Jurassic) extinctions. It is clear that there is no direct correlation between total volume of lava and extinction magnitude because there is always suffi cient recovery time between individual eruptions to negate any cumulative effect of successive fl ood basalt erup- tions. Instead, the environmental and climatic damage must be attributed to single- pulse gas effusions. It is notable that the best-constrained examples of death-by- volcanism record the main extinction pulse at the onset of (often explosive) volcanism (e.g., the Capitanian, end-Permian, and end-Triassic examples), suggesting that the rapid injection of vast quantities of volcanic gas (CO2 and SO2) is the trigger for a truly major biotic catastrophe. Warming and marine anoxia feature in many extinc- tion scenarios, indicating that the ability of a large igneous province to induce these proximal killers (from CO2 emissions and thermogenic greenhouse gases) is the single most important factor governing its lethality. -

Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality Greg Schwab University of Kentucky, [email protected]

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Agriculture and Natural Resources Publications Cooperative Extension Service 3-2007 Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality Greg Schwab University of Kentucky, [email protected] Lloyd W. Murdock University of Kentucky, [email protected] David C. Ditsch University of Kentucky, [email protected] Monroe Rasnake University of Kentucky, [email protected] Frank J. Sikora University of Kentucky, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/anr_reports Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Repository Citation Schwab, Greg; Murdock, Lloyd W.; Ditsch, David C.; Rasnake, Monroe; Sikora, Frank J.; and Frye, Wilbur, "Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality" (2007). Agriculture and Natural Resources Publications. 76. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/anr_reports/76 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Cooperative Extension Service at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agriculture and Natural Resources Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Greg Schwab, Lloyd W. Murdock, David C. Ditsch, Monroe Rasnake, Frank J. Sikora, and Wilbur Frye This report is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/anr_reports/76 ID-163 Agricultural Lime Recommendations Based on Lime Quality G.J. Schwab, L.W. Murdock, D. Ditsch, and M. Rasnake, UK Department of Plant and Soil Sciences; F.J. Sikora, UK Division of Regulatory Services; W. -

Lime Guidelines for Field Crops in New York

Lime Guidelines for Field Crops in New York. First Release. CSS E06-2. June 2006. LIME GUIDELINES FOR FIELD CROPS IN NEW YORK Quirine M. Ketterings, W. Shaw Reid, and Karl J. Czymmek Department of Crop and Soil Sciences Extension Series E06-2 Cornell University June 9, 2006 Quirine M. Ketterings is Associate Professor of Nutrient Management in Agricultural Systems, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Cornell University. W. Shaw Reid is Emeritus Professor of Soil Fertility, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Cornell University. Karl J. Czymmek is Senior Extension Associate in Field Crops and Nutrient Management with PRO-DAIRY, Cornell University. Lime Guidelines for Field Crops in New York. First Release. CSS E06-2. June 2006. Acknowledgments: We thank Carl Albers, Area Field Crops Extension Educator, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Steuben, Chemung, and Schuyler Counties, for his review of an earlier draft of this extension bulletin. Correct citation: Ketterings, Q.M., W.S. Reid, and K.J. Czymmek (2006). Lime guidelines for field crops in New York. First Release. Department of Crop and Soil Sciences Extension Series E06-2. Cornell University, Ithaca NY. 35 pages. Downloadable from: http://nmsp.css.cornell.edu/nutrient_guidelines/ For more information: For more information contact Quirine Ketterings at the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Cornell University, 817 Bradfield Hall, Ithaca NY 14583, or e- mail: [email protected]. Nutrient Management Spear Program Collaboration among the Cornell University Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, PRODAIRY and Cornell Cooperative Extension http://nmsp.css.cornell.edu/ Lime Guidelines for Field Crops in New York. First Release. -

Lime for Michigan Soils

Extension Bulletin E-471 • Revised • December 2010 LIME FOR MICHIGAN SOILS Darryl Warncke, Laura Bast and Don Christenson Department of Crop and Soil Sciences pplying lime to agricultural soils can provide farm- WHAT IS SOIL ACIDITY? ers with a very good return on investment. Long- Although the use of synthetic fertilizers contributes to soil term experiments in Michigan and other Great Lakes A acidity, soil acidification results from the natural leaching states indicate that every dollar spent on agricultural lime of calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) from the soil and the applied according to soil test recommendations returns decomposition of plant residues. Positively charged hydro- $5 to $10. Liming acid soils improves nutrient availability, gen ions in the soil solution (water in the soil) and on the microbial activity and overall soil productivity. Soil-applied surface of clay and organic matter particles that make up the lime neutralizes (or corrects) acidity, a soil chemical condi- soil contribute to the active acidity of the soil. Soil pH is tion that affects the growth of crops. Lime also supplies soil the measure of this active acidity. A pH value below 7.0 is with two essential plant nutrients: calcium and magnesium. acid, 7.0 is neutral, and above 7.0 is alkaline, Recent soil test summaries indicate that about 10 percent The amount or concentration of active acidity in the soil of Michigan’s 7.8 million acres of agricultural land need at solution depends on the number of hydrogen ions held by least 2.5 tons/acre of lime, for a total of 1.95 million tons the negatively charged soil particles of clay and organic mat- of lime needed statewide to neutralize soil acidity. -

Pelletized Lime for Short-Term Treatment of Soil Acidity Gene Stevens and David Dunn University of Missouri-Delta Research Center

Pelletized Lime for Short-Term Treatment of Soil Acidity Gene Stevens and David Dunn University of Missouri-Delta Research Center Correct soil pH is the cornerstone of a successful crop nutrient management program. Annual applications of nitrogen fertilizers on crops slowly produce acid conditions in fields. If low pH is not corrected by agricultural lime applications, soil acidity will reduce nutrient availability to plants (especially P), produce toxic levels of aluminum and manganese, and diminish the weed control activity of some herbicides. In recent years, agricultural fertilizer dealers have reported 2 to 3 fold increases in sales of pelletized lime. Pelletized lime is finely ground limestone, which is made into small pellets for broadcasting with conventional fertilizer equipment. Because pelletized lime is relatively expensive per ton, it is applied at lower rates (<300 lbs/acre) as compared to recommended rates of agricultural lime. A “1:10 ratio” rule of thumb has been promoted for comparing the short-term neutralizing effectiveness of pelletized lime to agricultural lime. (Example: if a soil test recommends the ENM equivalent of 2000 lbs of agricultural lime per acre apply 200 lbs of pelletized lime/acre). Most farmers realize that pelletized lime is not a long-term “fix”, but expect it to reduce soil acidity to tolerable levels for one year. Typically, farmers apply this material on fields that a landlord is unwilling to share part of the cost of applying agricultural lime or will not provide a lease agreement for more than one year. A study was initiated to evaluate the general philosophy of using finely ground lime to provide a short-term, “quick fix” of soil acidity and compare corn and cotton yield response of pelletized lime to agricultural lime. -

Lime for Acid Soils

Prepared for the Northern and Yorke NRM Board Lime for Acid Soils Sustainable Agriculture in the Northern and Yorke NRM Region. Lime is the most effective method for the treatment of acid soils. Within the Northern and Yorke Region there are more than 270,000 hectares of land susceptible to soil acidification that degrades the soil and reduces crop and pasture growth. Soil acidification tends to occur on the sands and sandy loams in the high rainfall areas, north of Kapunda through to Jamestown and from Crystal Brook through to Melrose with a smaller area around Redhill (Figure 1). Soil acidification is caused by an accumulation of hydrogen ions in the soil through the build-up of organic matter; addition and leaching of nitrogen from fertilisers and legumes and the removal of alkaline nutrients in plant and animal products. As the amount of hydrogen ions increases then soil acidity increases. When the soil falls below a soil pH of 5.0 (CaCl2) the productivity of even tolerant crops and pastures starts to fall, toxic amounts of aluminium can be released into the soil, microbial activity starts to decline and nutrients such as phosphorus, magnesium, calcium and molybdenum become less available. Table 1 shows the tolerance of plant species to soil acidity. Table 1: Tolerance of plants of soil acidity Species Tolerance Canola, faba beans, lucerne, annual medic Very Sensitive Barley, wheat, peas, phalaris Sensitive Lupins, wheat, sub-clover, cocksfoot, vetch, Tolerant fescue, perennial rye-grass Triticale, oats, seradella Very tolerant Lime for acid soils The use of lime will raise the soil pH and increase the productivity of crops and pastures. -

Liming Acid Soils in Tennessee

PB 1096 (Available online only) Liming Acid Soils in Tennessee Hubert Savoy Jr., Associate Professor, Biosystems Engineering and Soil Science and Debbie Joines, Manager, UT Soil, Plant and Pest Center What is Soil Acidity? Soil acidity refers to the level of acids present in soils. As acid levels increase, the pH of the soil decreases. While the pH scale ranges from 0-14, most Tennessee soils range in value from 4.5 to 7.5. Soils with pH values greater than 7.0 are alkaline or sweet, and those with values of less than 7.0 are acid or sour (Figure 1). As the soil pH decreases below 7.0, the amount of acidity rapidly increases. For example, a pH of 5.0 is 10 times more acidic than 6.0 and 100 times more acidic than a pH of 7.0. Soil test results indicate that approximately 40 to 60 percent of the cropland in Tennessee is too acidic for optimum crop production. Because of this, determining the need for lime by soil testing should be the first step in developing a sound crop fertilization program. Figure 1. The pH Scale (Source: NCSA). Lime neutralizes excess soil acids and increases soil pH which is a measure of soil acidity. Levels of Causes of Soil Acidity extractable aluminum (Al) and manganese (Mn) are Several factors contribute to soil acidity. Acid levels reduced to a nontoxic range as soil pH increases. If increase as basic nutrients (calcium, magnesium and not limed as needed, soils continue to become more potassium) are replaced by hydrogen through soil acidic, reducing the potential for production of healthy erosion, leaching and crop removal.