Actinide Ground-State Properties-Theoretical Predictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt. Ltd, Hyderabad, India. [email protected] Abstract Periodic table of chemical elements symbolizes an elegant graphical representation of symmetry at atomic level and provides an overview on arrangement of electrons. It started merely as tabular representation of chemical elements, later got strengthened with quantum mechanical description of atomic structure and recent studies have revealed that periodic table can be formulated using SO(4,2) SU(2) group. IUPAC, the governing body in Chemistry, doesn‟t approve any periodic table as a standard periodic table. The only specific recommendation provided by IUPAC is that the periodic table should follow the 1 to 18 group numbering. In this technical paper, we describe a new graphical representation of periodic table, referred as „Circular form of Periodic table‟. The advantages of circular form of periodic table over other representations are discussed along with a brief discussion on history of periodic tables. 1. Introduction The profoundness of inherent symmetry in nature can be seen at different depths of atomic scales. Periodic table symbolizes one such elegant symmetry existing within the atomic structure of chemical elements. This so called „symmetry‟ within the atomic structures has been widely studied from different prospects and over the last hundreds years more than 700 different graphical representations of Periodic tables have emerged [1]. Each graphical representation of chemical elements attempted to portray certain symmetries in form of columns, rows, spirals, dimensions etc. Out of all the graphical representations, the rectangular form of periodic table (also referred as Long form of periodic table or Modern periodic table) has gained wide acceptance. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

The Periodic Table of the Elements

The Periodic Table of the Elements The president of the Inorganic Chemistry Division, atomic number was the same as the number of protons Gerd Rosenblatt, recognizing that the periodic table in each element. of the elements found in the “Red Book” A problem for Mendeleev’s table was the position- (Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry, published in ing of the rare earth or lanthanoid* elements. These 1985) needed some updating—particularly elements elements had properties and atomic weight values above 103, including element 110 (darmstadtium)— similar to one another but that did not follow the reg- made a formal request to Norman Holden and Tyler ularities of the table. Eventually, they were placed in a Coplen to prepare an updated table. This table can be separate area below the main table. found below, on the IUPAC Web site, and as a tear-off The Danish physicist Niels Henrik David Bohr pro- on the inside back cover of this issue. posed his electronic orbital structure of the atom in 1921, which explained the problem of the rare earth by Norman Holden and Ty Coplen elements. The electrons in the outermost and the penultimate orbits are called valence electrons since generally their actions account for the valence of the he Russian chemist Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev element (i.e., electrons capable of taking part in the constructed his original periodic table in 1869 links between atoms). Chemical behavior of an ele- Tusing as its organizing principle his formulation ment depends on its valence electrons, so that when of the periodic law: if the chemical elements are only inner orbit electrons are changing from one ele- arranged in the ascending order of their atomic ment to another, there is not much difference in the weights, then at certain regular intervals (periods) chemical properties between the elements. -

ELECTRONEGATIVITY D Qkq F=

ELECTRONEGATIVITY The electronegativity of an atom is the attracting power that the nucleus has for it’s own outer electrons and those of it’s neighbours i.e. how badly it wants electrons. An atom’s electronegativity is determined by Coulomb’s Law, which states, “ the size of the force is proportional to the size of the charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them”. In symbols it is represented as: kq q F = 1 2 d 2 where: F = force (N) k = constant (dependent on the medium through which the force is acting) e.g. air q1 = charge on an electron (C) q2 = core charge (C) = no. of protons an outer electron sees = no. of protons – no. of inner shell electrons = main Group Number d = distance of electron from the nucleus (m) Examples of how to calculate the core charge: Sodium – Atomic number 11 Electron configuration 2.8.1 Core charge = 11 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +1 (Group i) Chlorine – Atomic number 17 Electron configuration 2.8.7 Core charge = 17 (no. of p+s) – 10 (no. of inner e-s) +7 (Group vii) J:\Sciclunm\Resources\Year 11 Chemistry\Semester1\Notes\Atoms & The Periodic Table\Electronegativity.doc Neon holds onto its own electrons with a core charge of +8, but it can’t hold any more electrons in that shell. If it was to form bonds, the electron must go into the next shell where the core charge is zero. Group viii elements do not form any compounds under normal conditions and are therefore given no electronegativity values. -

UNIT 11 CHEMISTRY of D- Andf-BLOCK ELEMENTS

UNIT 11 CHEMISTRY OF d- ANDf-BLOCK ELEMENTS Structure 11.1 Introduction Objectives 11.2 Transition and Inner Transition Elements - An Introduction 11.3 IUPAC Nomenclature of 6d Transition Series Elements 11.4 .Electronic Configuration of d-Block and f-Block Elements Electronic Configurations of Transition Elements and Ions Electronic Configurations of Lanthanide and Actinide Elements 11.5 Periodic Trends in Properties Atomic Radii and Ioaic Rad~i Melting and Boiling Points Enthalpies of Ionization Oxidation States Colour of the Complexes Magnetic Properties Catalytic Properties Formation of Complexes Formation of Interstitial Compounds (Interstitial Solid Solutions) and Alloys (Substitutional Solid Solutions) 11.6 Summary 11.7 Terminal Questions 11.1 INTRODUCTION In last unit we have studies about the periodicity and representative elements. In this unit we will study the chemistry of d and f block elements. First we will study the IUPAC nomenclature of these elements then we will discuss the electronic configuration, periodicity, variation of size, melting and boiling points. We shall also study the ionization energy, electronegativity, electrode potential, oxidation sate of these elements in detail. Objectives After studying this unit, you should be able to: explain the IUPAC nomenclature of d and f block elements, describe the electronic configuration of d and f block elements, outline the general properties of these elements, and discuss the colour, magnetic complex formation catalytic properties. 1 1.2 TRANSITION AND INNER TRANSITION ELEMENTS - AN INTRODUCTION We already know that in the periodic table the elements are classified into four blocks; namely, s-block, p-block, d-block andfiblock, based on the name of atomic orbital that accepts the valence or differentiating electrons. -

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes Arrangement of the known elements based on atomic number and chemical and physical properties. Divided into three basic categories: Metals (left side of the table) Nonmetals (right side of the table) Metalloids (touching the zig zag line) Basic Organization by: Atomic structure Atomic number Chemical and Physical Properties Uses of the Periodic Table Useful in predicting: chemical behavior of the elements trends properties of the elements Atomic Structure Review: Atoms are made of protons, electrons, and neutrons. Elements are atoms of only one type. Elements are identified by the atomic number (# of protons in nucleus). Energy Levels Review: Electrons are arranged in a region around the nucleus called an electron cloud. Energy levels are located within the cloud. At least 1 energy level and as many as 7 energy levels exist in atoms Energy Levels & Valence Electrons Energy levels hold a specific amount of electrons: 1st level = up to 2 2nd level = up to 8 3rd level = up to 8 (first 18 elements only) The electrons in the outermost level are called valence electrons. Determine reactivity - how elements will react with others to form compounds Outermost level does not usually fill completely with electrons Using the Table to Identify Valence Electrons Elements are grouped into vertical columns because they have similar properties. These are called groups or families. Groups are numbered 1-18. Group numbers can help you determine the number of valence electrons: Group 1 has 1 valence electron. Group 2 has 2 valence electrons. Groups 3–12 are transition metals and have 1 or 2 valence electrons. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Chapter 7 Periodic Properties of the Elements Learning Outcomes

Chapter 7 Periodic Properties of the Elements Learning Outcomes: Explain the meaning of effective nuclear charge, Zeff, and how Zeff depends on nuclear charge and electron configuration. Predict the trends in atomic radii, ionic radii, ionization energy, and electron affinity by using the periodic table. Explain how the radius of an atom changes upon losing electrons to form a cation or gaining electrons to form an anion. Write the electron configurations of ions. Explain how the ionization energy changes as we remove successive electrons, and the jump in ionization energy that occurs when the ionization corresponds to removing a core electron. Explain how irregularities in the periodic trends for electron affinity can be related to electron configuration. Explain the differences in chemical and physical properties of metals and nonmetals, including the basicity of metal oxides and the acidity of nonmetal oxides. Correlate atomic properties, such as ionization energy, with electron configuration, and explain how these relate to the chemical reactivity and physical properties of the alkali and alkaline earth metals (groups 1A and 2A). Write balanced equations for the reactions of the group 1A and 2A metals with water, oxygen, hydrogen, and the halogens. List and explain the unique characteristics of hydrogen. Correlate the atomic properties (such as ionization energy, electron configuration, and electron affinity) of group 6A, 7A, and 8A elements with their chemical reactivity and physical properties. Development of Periodic Table •Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer (~1869) independently came to the same conclusion about how elements should be grouped in the periodic table. •Henry Moseley (1913) developed the concept of atomic numbers (the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom) 1 Predictions and the Periodic Table Mendeleev, for instance, predicted the discovery of germanium (which he called eka-silicon) as an element with an atomic weight between that of zinc and arsenic, but with chemical properties similar to those of silicon. -

Organometallic Pnictogen Chemistry

Institut für Anorganische Chemie 2014 Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie | Sabine Reisinger aus Regensburg, geb. Scheuermayer am 15.07.1983 Studium: Chemie, Universität Regensburg Abschluss: Diplom Promotion: Prof. Dr. Manfred Scheer, Institut für Anorganische Chemie Sabine Reisinger Die vorliegende Arbeit enthält drei Kapitel zu unterschiedlichen Aspekten der metallorganischen Phosphor- und Arsen-Chemie. Zunächst werden Beiträge zur supramolekularen Chemie mit 5 Pn-Ligandkomplexen basierend auf [Cp*Fe(η -P5)] und 5 i [Cp*Fe(η - Pr3C3P2)] gezeigt, gefolgt von der Eisen-vermittelten Organometallic Pnictogen Aktivierung von P4, die zu einer selektiven C–P-Bindungsknüpfung führt, während das dritte Kapitel die Verwendung von Phosphor Chemistry – Three Aspects und Arsen als Donoratome in mehrkernigen Komplexen mit paramagnetischen Metallionen behandelt. Sabine Reisinger 2014 Alumniverein Chemie der Universität Regensburg E.V. [email protected] http://www.alumnichemie-uniregensburg.de Aspects Three – Chemistry Pnictogen Organometallic Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie ISBN 978-3-86845-118-4 Universität Regensburg Universitätsstraße 31 93053 Regensburg www.uni-regensburg.de 9 783868 451184 4 Sabine Reisinger Organometallic Pnictogen Chemistry – Three Aspects Organometallic Pnictogen Chemistry – Three Aspects Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Sabine Reisinger, geb. Scheuermayer Regensburg 2014 Die Arbeit wurde von Prof. Dr. Manfred Scheer angeleitet. Das Promotionsgesuch wurde am 20.06.2014 eingereicht. Das Kolloquium fand am 11.07.2014 statt. Prüfungsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Helmut Motschmann 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Manfred Scheer 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Henri Brunner weiterer Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Dick Dissertationsreihe der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie der Universität Regensburg, Band 4 Herausgegeben vom Alumniverein Chemie der Universität Regensburg e.V. -

Periodic Table Key Concepts

Periodic Table Key Concepts Periodic Table Basics The periodic table is a table of all the elements which make up matter Elements initially grouped in a table by Dmitri Mendeleev Symbols – each element has a symbol which is either a Capital Letter or a Capital Letter followed by a lower case letter Atomic Number – the number above an element’s symbol which shows the number of protons Atomic Mass – the number found below an elements symbol which shows the mass of the element. Mass = the number of protons + the number of neutrons Metals – the elements which have the properties of malleability, luster, and conductivity o These elements are good conductors of electricity & heat. o Found to the left of the zig-zag line on the periodic table Nonmetals – do not have the properties of metals. Found to the right of the zig-zag line Metalloids – elements found along the zig-zag line of the periodic table and have some properties of metals and nonmetals (B, Si, Ge, As, Sb, Te, and Po) Groups The columns going up and down (There are 18 groups) Group 1: Hydrogen, Lithium, Sodium, Potassium, Rubidium, Cesium, and Francium Elements arranged so that elements with similar properties would be in the same group. o Group 1 Alkali Metals - highly reactive metals o Group 2 Alkali Earth Metals – reactive metals o Group 3-12 Transition Metals o Group 17 Halogens – highly reactive non-metals o Group 18 Noble Gases - do not react or combine with any other elements. Elements are grouped according to their properties or reactivity Reactivity is determined by the number of electrons in an element’s outer energy level These electrons are called valence electrons Periods The rows that run from left to right on the periodic table (There are 7 periods) Period 1 contains 2 elements, Hydrogen and Helium. -

Atomic Radius

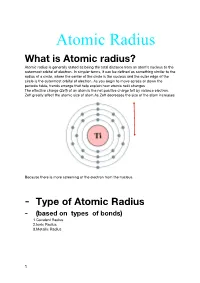

Atomic Radius What is Atomic radius? Atomic radius is generally stated as being the total distance from an atom’s nucleus to the outermost orbital of electron. In simpler terms, it can be defined as something similar to the radius of a circle, where the center of the circle is the nucleus and the outer edge of the circle is the outermost orbital of electron. As you begin to move across or down the periodic table, trends emerge that help explain how atomic radii changes The effective charge (Zeff) of an atom is the net positive charge felt by valance electron. Zeff greatly affect the atomic size of atom.As Zeff decreases the size of the atom increases Because there is more screening of the electron from the nucleus - Type of Atomic Radius - (based on types of bonds) 1.Covalent Radius 2.Ionic Radius 3.Metallic Radius 1 Covalent radius When a covalent bond is present between two atoms, the covalent radius can be determined. When two atoms of the same element are covalently bonded, the radius of each atom will be half the distance between the two nuclei because they equally attract the electrons. The distance between two nuclei will give the diameter of an atom, but you want the radius which is half the diameter. Ionic radius The ionic radius is the radius of an atom forming ionic bond or an ion. The radius of each atom in an ionic bond will be different than that in a covalent bond. This is an important concept. The reason for the variability in radius is due to the fact that the atoms in an ionic bond are of greatly different size. -

Periodic Table Trends Periodic Trends

Periodic Table Trends Periodic Trends • Atomic Radius • Ionization Energy • Electron Affinity The Trends in Picture Atomic Radius • Unlike a ball, an atom has fuzzy edges. • The radius of an atom can only be found by measuring the distance between the nuclei of two touching atoms, and then dividing that distance by two. Atomic Radius • Atomic radius is determined by how much the electrons are attracted to the positive nucleus. • The fewer the electrons in each period, the lesser the attraction. • Lesser attraction = • larger nucleus Atomic Radius Trend • Period: in general, as we go across a period from left to right, the atomic radius decreases – Effective nuclear charge increases, therefore the valence electrons are drawn closer to the nucleus, decreasing the size of the atom • Family: in general, as we down a group from top to bottom, the atomic radius increases – Orbital sizes increase in successive principal quantum levels Concept Check • Which should be the larger atom? Why? • O or N N • K or Ca K • Cl or F Cl • Be or Na Na • Li or Mg Mg Ionization Energy • Energy required to remove an electron from an atom • Which atom would be harder to remove an electron from? • Na Cl Ionization Energy • X + energy → X+ + e– X(g) → X+ (g) + e– • First electron removed is IE1 • Can remove more than one electron (IE2 , IE3 ,…) Ex. Magnesium Mg → Mg+ + e– IE1 = 735 kJ/mol Mg+ → Mg2+ + e– IE2 = 1445 kJ/mol Mg2+ → Mg3+ + e– IE3 = 7730 kJ/mol* *Core electrons are bound much more tightly than valence electrons Periodic Ionization Trend • Trend: • Period: