Neoclassical Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fernando V. Ferreira

FERNANDO V. FERREIRA The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Phone: (215) 898-7181 430 Vance Hall Email: [email protected] 3733 Spruce Street http://real-faculty.wharton.upenn.edu/fferreir/ Philadelphia, PA 19104-6301 Updated: February 2021 EMPLOYMENT C. F. Koo Professor, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Departments of Real Estate, and Business Economics and Public Policy, 2019-present C. F. Koo Associate Professor, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Departments of Real Estate, and Business Economics and Public Policy, 2018-2019 Associate Professor, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Departments of Real Estate, and Business Economics and Public Policy, 2011-2017 Assistant Professor, The Wharton School, Real Estate Department, 2004-2011 EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics, University of California, Berkeley, 1999-2004 M.A. in Economics, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 1997-1999 B.A. in Economics, State University of Maringa, Brazil, 1992-1996 UNIVERSITY SERVICE Ph.D. Coordinator, Wharton Applied Economics Program, 2012-2014, 2016-2019 Ph.D. Co-Coordinator, Wharton Applied Economics Program, 2006-2011 Recruiting Committee Chair, 2012-2014, 2016, 2019 Graduate Council of the Faculties, 2012-2014 Wharton Dean’s Advisory Council, 2012-2013 PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES AND OTHER POSITIONS Co-Organizer, NBER Summer Institute Real Estate Meeting, 2014-present Co-Editor, Journal of Public Economics, 2013-2018 Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 2008-present Faculty Fellow, Penn Institute for Urban Research, 2009-present Visiting Scholar, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2006-present Visiting Scholar, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2010, 2016, and 2017 Visiting Scholar, Nova School of Business and Economics, 2014-2015 RECENT CONSULTING ACTIVITIES Google X RESEARCH AND PUBLICATIONS Published and Forthcoming Articles “The Role of Price Spillovers in the American Housing Boom”, with Anthony DeFusco, Wenjie Ding, and Joseph Gyourko. -

Mark Rubinstein

MARK RUBINSTEIN Email: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND Preparatory Work: The Lakeside School, Seattle, 1956-1962 Undergraduate: Harvard College, 1962-1966 Major: Economics A.B. Degree, Magna Cum Laude, June 1966 Graduate Studies: Stanford University, 1966-1968 Graduate School of Business Area of Concentration: Finance M.B.A. Degree, June 1968 UCLA, 1968-1971 Graduate School of Business Field: Finance Ph.D. Degree, December 1971 RELEVANT WORK EXPERIENCE July 1967 - Sept 1967 Security Analyst Capital Research and Management Company Los Angeles, California July 1968 - June 1969 Chief Economic Analyst Commuter Centers, Inc. Los Angeles, California July 1969 - Sept 1969 Cost Accountant Whitney Fidalgo Seafoods, Inc. Seattle, Washington April 1976 - June 1976 Member, Options Market-Maker Pacific Stock Exchange San Francisco, California Feb 1981 - July 1984 Founding Principal and Executive Vice-President Leland O'Brien Rubinstein Associates Century City, California July 1984 – July 1995 Founding Principal and Director Leland O'Brien Rubinstein Associates Los Angeles, California Nov 1989 - July 1995 Director SuperShare Services Corporation Los Angeles, California FINANCIAL CONSULTING ACTIVITY Current: Past: Nov 1975 Pacific Stock Exchange (rules for underlying stocks for listing options) Feb-Apr 1977 Philadelphia Stock Exchange (economic justification of options on market index) Jan 1978-Mar 1979 Expert witness in Murray Case (security brokerage fraud) Apr 1978-Jul 1982 Expert witness in Blank Case (security brokerage fraud) Sep 1978-Jun 1979 Expert witness in Harris Case (security brokerage fraud) Sep-Oct 1979 Technique for valuing options on bonds Oct 1979-Feb 1981 Expert witness in Piron Case (security brokerage fraud) Jul 1984-May 1994 Leland O'Brien Rubinstein Associates (general consulting) Jul 1985-Dec 1995 Tradelink Corp. -

Registration Requirements for Foreign Securities

Financial Economists Roundtable Statement on Registration Requirements for Foreign Securities July 28, 1993 We the undersigned members of the Financial Economists Roundtable (FER) propose that American investors be allowed to trade the shares of major foreign companies as easily as they now trade the shares of U.S. companies. Our proposal should be viewed as a first step towards eliminating the regulatory impediments that now preclude the securities of most foreign firms from being traded on the principal U.S. equity markets. The Securities and Exchange Commission now requires foreign firms that wish to have their securities traded in these markets to register under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and, among other things, reconcile quantitatively their financial statements to U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (U.S. GAAP). This registration requirement hinders U.S. investors and exchanges in trading foreign shares. Eliminating impediments to the trading of foreign shares will enhance the competitive position of the United States in world equity markets and reduce the cost to U.S. investors, who trade these shares. Our proposal to facilitate the trading of foreign shares in U.S. markets is consistent with the principal elements of a recent suggestion made by the New York Stock Exchange. We propose that the equities of very large foreign companies be made eligible to be traded and/or listed in the United States on registered exchanges and on NASDAQ without conforming to all current SEC registration requirements. To be traded on U.S. equity markets, foreign companies would need to have available only their customary financial statements, independently audited, and have revenues of at least 3 billion dollars and a market capitalization of at least 1 billion dollars. -

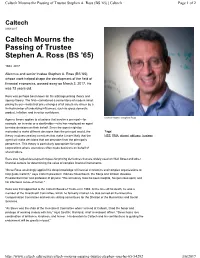

Stephen A. Ross (BS '65) | Caltech Page 1 of 2

Caltech Mourns the Passing of Trustee Stephen A. Ross (BS '65) | Caltech Page 1 of 2 Caltech 03/04/2017 Caltech Mourns the Passing of Trustee Stephen A. Ross (BS '65) 1944–2017 Alumnus and senior trustee Stephen A. Ross (BS '65), whose work helped shape the development of the field of financial economics, passed away on March 3, 2017. He was 73 years old. Ross was perhaps best known for his arbitrage pricing theory and agency theory. The first—considered a cornerstone of modern asset pricing theory—holds that price changes of all assets are driven by a limited number of underlying influences, such as gross domestic product, inflation, and investor confidence. Caltech trustee Stephen Ross Agency theory applies to situations that involve a principal—for example, an investor or a stockholder—who has employed an agent to make decisions on their behalf. Since the agent might be motivated to make different decisions than the principal would, the Tags: theory involves creating incentives that make it more likely that the HSS, PMA, alumni, obituary, trustees agent will make decisions that are desirable from the principal's perspective. This theory is particularly appropriate for large corporations where executives often make decisions on behalf of shareholders. Ross also helped develop techniques for pricing derivatives that are widely used on Wall Street and other financial centers for determining the value of complex financial instruments. "Steve Ross unstintingly applied his deep knowledge of financial economics and complex organizations to help guide Caltech," says Caltech president Thomas Rosenbaum, the Sonja and William Davidow Presidential Chair and professor of physics. -

The Modigliani-Miller Theorem at 60: the Long-Overlooked Legal Applications of Finance’S Foundational Theorem

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 2018 The Modigliani-Miller Theorem at 60: The Long-Overlooked Legal Applications of Finance’s Foundational Theorem Michael S. Knoll University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Corporate Finance Commons, Courts Commons, Economic Theory Commons, Finance Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Knoll, Michael S., "The Modigliani-Miller Theorem at 60: The Long-Overlooked Legal Applications of Finance’s Foundational Theorem" (2018). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 1936. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1936 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Modigliani-Miller Theorem at 60: The Long-Overlooked Legal Applications of Finance’s Foundational Theorem Michael S. Knoll† 2018 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller’s The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance, and the Theory of Investment, which purports to demonstrate that a firm’s value is independent of its capital structure. Widely hailed as the foundation of modern finance, their article is little known by lawyers and legal academics even though it led to many major economic advances, such as agency costs and asymmetric information, recognized and used throughout the law today. -

Editor's Letter 4

Where Have Thirty Years Gone? A trap for logicians? Peter L. Bernstein ll well-behaved papers in finance begin with the cles), Franco Modigliani (one article), Paul Samuelson (six statement of a hypothesis or an assertion about articles), William Sharpe (eight articles), James Tobin (one theory. Most articles then go on to present some article), if we include the ten marvelous articles contributed by historical background on the subject matter and, Fischer Black, in the high confidence that he would have Aat greater length, empirical data to substantiate the author’s become a laureate if his life had not been cut short before option arguments. On this occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of pricing theory won the award. Black and Samuelson both The Journal of Portfolio Management, I take the liberty of appeared in our maiden issue in the fall of 1974. reversing the standard sequence. What has all that massive accumulated effort by authors, editors, referees, copy editors, printers, proofreaders, and the EMPIRICS staff at Institutional Investor added to the stock of human knowl- edge? We have every reason to believe the Journal has added Arithmetic was my first thought when I sat down to draft a great deal, judging by the frequency of citations in other pub- this essay. Four issues a year averaging eleven articles per issue lications and by the continuing high quality of both authors and over thirty years works out to 1,320 articles. The articles on their contributions. average use about six pieces of paper, each nine inches long. That is a necessary condition of success, but it may not by guest on September 27, 2021. -

Markus K. Brunnermeier EDWARDS S

Markus K. Brunnermeier EDWARDS S. SANFORD PROFESSOR Director of Bendheim Center for Finance Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544, USA [email protected] scholar.princeton.edu/markus ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Princeton University, Department of Economics Bendheim Center for Finance, Director 2014-present International Economics Section Department of Operational Research and Financial Engineering Julis-Rabinowitz Center, Princeton School of Public & Intern. Affairs, Founding Director 2011-2014 Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Economics 2008-present Professor of Economics 2006-2008 Assistant Professor of Economics 1999-2006 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Research Associate, Asset Pricing, Fluctuation & Growth, International, Monetary 2006-present Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Research Affiliate 2003-present U.S. Congressional Budget Office, Panel of Economic Advisers 2014-present CESifo, Research Fellow, Director of Macro, Money and International Finance 2004-present Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Council (chair from 2019) 2012-present Luohan Academy (Alibaba/Ant Financial), Committee Member of the Academy 2018-present Peterson Institute for International Economics, Non-Resident Senior Fellow 2020-present International Monetary Fund Visiting Scholar 2020-present Advisory Group on Global Marco-Financial Tail Risks 2011-2019 Federal Reserve Bank of New York Monetary Policy Advisory Panel 2010-2019 Financial Advisory Roundtable 2006-2015 Academic Consultant 2004-2011 European Systemic Risk Board, Advisory Scientific -

The Legacy of Stephen A. Ross

THE JOURNAL OF PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT OF PORTFOLIO THE JOURNAL jpm.iprjournals.com SPECIAL ISSUE D E D I C AT E D TO Stephen A. Ross EDITORS: Frank J. Fabozzi | Bruce I. Jacobs | Kenneth N. Levy CONTRIBUTORS: Jonathan B. Berk | Stephen J. Brown | John Y. Campbell | Ludwig B. Chincarini Maggie Copeland | Michael Copeland | Thomas Copeland | Philip H. Dybvig | Edwin J. Elton Frank J. Fabozzi | William N. Goetzmann | Mark Grinblatt | Richard Grinold Martin J. Gruber | Bruce I. Jacobs | Leonid Kogan | Kenneth N. Levy | Marcos López de Prado SPECIAL ISSUE Ian Martin | David K. Musto | Dimitris Papanikolaou | Konark Saxena • JUNE 2018 IPRJOURNALS . COM EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION The Legacy of Stephen A. Ross FRANK J. FABOZZI, BRUCE I. JACOBS, AND KENNETH N. LEVY FRANK J. FABOZZI tephen A. Ross was a towering intel- Many of his former students and col- is a professor of finance lect. He will be remembered for a leagues have contributed to this special at the EDHEC Business body of work that has transformed issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management. School and a member of the EDHEC Risk Institute finance and continues to influence Their articles discuss what they learned from Sand inspire financial research and practice. Steve, how Steve’s ideas influenced their in Nice, France. [email protected] His foundational concepts include agency own research, and how these ideas are being theory, the arbitrage pricing theory (APT), adapted and refined for current and future BRUCE I. JACOBS risk-neutral pricing, and the recovery the- financial markets. Ludwig Chincarini and is principal at Jacobs Levy orem. His contributions to the Cox–Ross– Frank Fabozzi’s “Stephen A. -

Financial Economics Under Symmetric Information

FALL 2009 Prof. Markus K. Brunnermeier email: [email protected] http://www.princeton.edu/~markus Office: 209 Dial Lodge Office Hours: Mo 4:25-5:30 pm ECO467: Institutional Finance Financial Crises, Risk Management and Liquidity Time and Location: Monday 1:30 am – 4:20 pm, BCF 103 Course Description: Financial institutions play an increasingly dominant role in modern finance. This course studies financial institutions and focuses on the stability of the financial system. It covers important theoretical concepts and recent developments in financial intermediation, asset pricing under asymmetric information, behavioral finance and market microstructure. Topics include market efficiency, asset price bubbles, herding, liquidity crises, risk management, market design and financial regulation. The course also studies different trading strategies - that are primarily employed by hedge funds and proprietary trading desks. A software that simulates the environment that professionals face on a trading desk will give students a more realistic and memorable learning experience and will illustrate certain theoretical concepts more vividly. The financial markets simulator “upTick” was developed by Professors Joshua Coval and Eric Stafford at Harvard University. Details about the financial markets simulator can be found at http://www.uptick-learning.com. Please download the software and install it at your laptop (please refer to the document posted on Blackboard for installing). In order to participate in the trading simulation who have to connect your (Windows) laptop to the Ethernet in BCF 103. You will also receive an Ethernet cable which enables to connect your laptop in the classroom for free. (Please do not lose it.) Before each simulation, students should run practice simulation at home and build “calculators” which help them to improve their trading performance. -

Constantinides August 30, 2001

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES RATIONAL ASSET PRICES George M. Constantinides Working Paper 8826 http://www.nber.org/papers/w8826 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2002 I thank John Campbell, Gene Fama, Chris Geczy, Lars Hansen, John Heaton, Rajnish Mehra, Lubos Pastor, Dick Thaler, and particularly Alon Brav and John Cochrane, for their insightful comments and constructive criticism. Finally, I thank Lior Menzly, for his excellent research assistance and insightful comments throughout this project. Naturally, I remain responsible for errors. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2002 by George M. Constantinides. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Rational Asset Prices George M. Constantinides NBER Working Paper No. 8826 March 2002 JEL No. G1, E2, E3 ABSTRACT The mean, co-variability, and predictability of the return of different classes of financial assets challenge the rational economic model for an explanation. The unconditional mean aggregate equity premium is almost seven percent per year and remains high after adjusting downwards the sample mean premium by introducing prior beliefs about the stationarity of the price-dividend ratio and the (non) forecastability of the long-term dividend growth and price-dividend ratio. Recognition that idiosyncratic income shocks are uninsurable and concentrated in recessions contributes toward an explanation. Also borrowing constraints over the investors’ life cycle that shift the stock market risk to the saving middle-aged consumers contribute toward an explanation. -

FIN 526/ECON581 Empirical Asset Pricing Module 4, 2015-2016 Course Information

FIN 526/ECON581 Empirical Asset Pricing Module 4, 2015-2016 Course Information Instructor: Hyun Joong Im Office: PHBS Building, Room 645 Phone: 86-755-2603-3627 Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Wednesdays 4:00-6:00 Teaching Assistant: Janghoon Shon Phone: 86-186-0103-6794 Email: [email protected] Classes: Lectures: Tuesdays and Fridays, 3:30-2:20 Venue: PHBS Building, Room TBA Course Website: Course materials will be distributed in the class. 1. Course Description 1.1 Context Course overview: The objective of this course is to read and understand scientific papers in empirical asset pricing. This course will focus on selected empirical papers regarding various asset pricing issues as well as basic research methodologies used in empirical asset pricing. Any empirical research should be based on theoretical foundations, so this course will explore selected theoretical models upon which empirical applications are based. The goal of this course is to combine econometrics, micro- and macro-economics, with a view to understanding, interpreting and predicting movements in stock prices. Prerequisites: Advanced Econometrics I 1.2 Textbooks and Reading Materials (1) My recommended text books are as follows. You must buy these two books. John H. Cochrane, “Asset Pricing,” Princeton University Press, 2001 John Y. Campbell, Andrew Lo, and A. Craig Mackinlay, “The Econometrics of Financial Markets,” Princeton University Press, 1997 Page 1 of 4 (2) In addition to the textbooks, I recommend a number of academic papers including the following survey articles. Summers, Lawrence H., “On Economics and Finance,” Journal of Finance 40: 633-635, July 1985. -

Curriculum Source References the Following References Were Used In

Curriculum Source References The following references were used in the CFA Institute-produced publications Quantitative Methods for Investment Analysis, Analysis of Equity Investments: Valuation, and Managing Investment Portfolios: A Dynamic Process. Ackerman, Carl, Richard McEnally, and David Ravenscraft. 1999. “The Performance of Hedge Funds: Risk, Return, and Incentives.” Journal of Finance. Vol. 54, No. 3: 833–874. ACLI Survey. 2003. The American Council of Life Insurers. Agarwal, Vikas and Narayan Naik. 2000. “Performance Evaluation of Hedge Funds with Option- Based and Buy-and-Hold Strategies.” Working Paper, London Business School. Ali, Paul Usman and Martin Gold. 2002. “An Appraisal of Socially Responsible Investments and Implications for Trustees and Other Investment Fiduciaries.” Working Paper, University of Melbourne. Almgren, Robert and Neil Chriss. 2000/2001. “Optimal Execution of Portfolio Transactions.” Journal of Risk. Vol. 3: 5–39. Altman, Edward I. 1968. “Financial Ratios, Discriminant Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy.” Journal of Finance. Vol. 23: 589–699. Altman, Edward I. and Vellore M. Kishore. 1996. “Almost Everything You Wanted to Know about Recoveries on Defaulted Bonds.” Financial Analysts Journal. Vol. 52, No. 6: 57−63. Altman, Edward I., R. Haldeman, and P. Narayanan. 1977. “Zeta Analysis: A New Model to Identify Bankruptcy Risk of Corporations.” Journal of Banking and Finance. Vol. 1: 29−54. Ambachtsheer, Keith, Ronald Capelle, and Tom Scheibelhut. 1998. “Improving Pension Fund Performance.” Financial Analysts Journal. Vol. 54, No. 6: 15–21. Ambachtsheer, Keith. 1986. Pension Funds and the Bottom Line: Managing the Corporate Pension Fund as a Financial Business. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin. American Accounting Association Financial Accounting Standards Committee.