Positive Emotion Persistence (PEP) in Bipolar Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

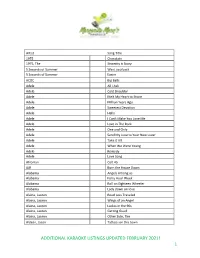

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

You Can Choose to Be Happy

You Can Choose To Be Happy: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression with Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. YOU CAN CHOOSE TO BE HAPPY: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression With Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. Palm Desert, California 92260 Revised (Second) Edition, 2010 First Edition, 1998; Printings, 2000, 2002. Copyright © 2010 by Tom G. Stevens PhD. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews; or except as provided by U. S. copyright law. For more information address Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. The cases mentioned herein are real, but key details were changed to protect identity. This book provides general information about complex issues and is not a substitute for professional help. Anyone needing help for serious problems should see a qualified professional. Printed on acid-free paper. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stevens, Tom G., Ph.D. 1942- You can choose to be happy: rise above anxiety, anger, and depression./ Tom G. Stevens Ph.D. –2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9653377-2-4 1. Happiness. 2. Self-actualization (Psychology) I. Title. BF575.H27 S84 2010 (pbk.) 158-dc22 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009943621 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ..................................................................................................................... -

THE STORY of Too Good to Go

THE STORY OF Too Good To Go ZERO WASTE CONSUMPTION & PRODUCTION # 7 3,5 years after saving its first meal in Copenhagen, the company Too Good To Go has now saved 29 million meals and avoided the equivalent of more than 72,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions, the equivalent of 15,000 vehicles driven for one year. Through a community of 18 million users called “waste warriors” and 38,000 restaurants, supermarkets and cafes in 14 countries, the company is managing to save one meal per second and is continuing to expand year after year. CONTEXT bakeries is sold at a lower price, From Denmark’s capital, the idea the goal was to generate revenue quickly spread, with users and One third of all food produced from food that would have entrepreneurs alike seeing the today ends up in a bin, where otherwise been wasted. By doing appeal of it. This was especially it is at best fed to animals or so, the company effectively acts true in France, Norway, and the recycled, and at worst it is on around 17% of the total food UK, where the model was quickly sent to landfill or incineration. waste in Europe by providing replicated. The company then Not only does this issue pose beneficial solutions at the food quickly expanded into many serious ethical and social service, wholesale and retail European countries such as questions, but it also deeply levels. Poland, Austria, Switzerland, threatens the environment. Portugal, Belgium and the Food waste is responsible for Netherlands. 10% of all global greenhouse gas emissions and 28% of HOW DID IT ALL BEGIN? The rationale behind Too Good agricultural lands worldwide to Go is simple; to connect are used to produce food Founded in 2015, Too Good consumers with businesses that’s destined to be ultimately To Go saved its first meal in whose products would wasted. -

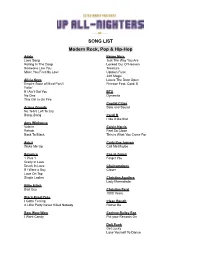

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

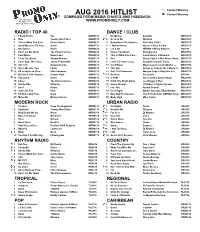

AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED from MEDIA CHARTS and FEEDBACK the Industry's #1 Source for Music & Music Video

Content Warning AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED FROM MEDIA CHARTS AND FEEDBACK The Industry's #1 Source For WWW.PROMOONLY.COM Music & Music Video RADIO / TOP 40 DANCE / CLUB 1 Cheap Thrills Sia MSR0416 1 No Money Galantis MSC0816 2 Ride Twenty One Pilots MSR0516 2 Needed Me Rihanna MSC0816 3 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris MSR0616 3 Bring Back The Summe... Rain Man f./OLY MSC0716 4 Send My Love (To You... Adele MSR0716 4 I Wanna Know Alesso f./Nico & Vinz MSC0716 5 One Dance Drake MSR0516 5 Let It Go NERVO f./Nicky Romero RC0716 6 Don't Let Me Down The Chainsmokers MSR0416 6 Chase You Down Runaground MSC0516 7 Cold Water Major Lazer MSR0916 7 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris f./Rihanna MSC0816 8 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes MSR0716 8 Sex Cheat Codes x Kris Kross Amst... MSC0716 9 Can't Stop The Feeli... Justin Timberlake MSR0616 9 Livin' For Your Love... Rosabel f./Jeanie Tracy MSC0616 10 Into You Ariana Grande MSR0816 10 Cold Water Major Lazer f./Justin Bieber ... MSC0916 11 Never Be Like You Flume MSR0516 11 This Girl Kungs vs Cookin' On 3 Burners MSC0816 12 All In My Head (Flex... Fifth Harmony MSR0716 12 Safe Till Tomorrow Morgan Page f./Angelika Vee MSC0716 13 We Don't Talk Anymor... Charlie Puth MSR0716 13 Bonbon Era Istrefi RC0816 14 Too Good Drake MSR0816 14 ILYSM Steve Aoki & Autoerotique MSC0916 15 Closer The Chainsmokers MSR0916 15 Drink The Night Away Lee Dagger f./Bex MSC0616 16 Needed Me Rihanna MSR0816 16 Sweet Dreams JX Riders f./Skylar Stecker MSC0916 17 Gold Kiiara MSR0716 17 Into You Ariana Grande MSC0816 18 Just Like Fire Pink MSR0816 18 Do It Right Martin Solveig f./Tkay Maidza MSC0816 19 Sit Still, Look Pret.. -

Too Good for Drugs Session 1 Goal Setting Over the Next 10 Sessions, We Will Learn Important Life Skills That Will Help You Stay Happy, Healthy, and Confident

Too Good for Drugs Session 1 Goal Setting Over the next 10 sessions, we will learn important life skills that will help you stay happy, healthy, and confident. Some of these skills include: setting and reaching goals, managing emotions, and making healthy choices. Goals can be short term or long term. An example of a short term goal is, “I want to level up in Minecraft.” And an example of a long term goal would be, “I want to graduate from high school.” When creating a goal, you want to make sure to name it. Say things like, “I can do it,” or “Go for it,” and always make sure to celebrate your successes. (Even the small ones) Next we’re going to watch 2 videos. In the first video you will see a little girl named Tinka. Tinka wants to save her money to get a new scooter. She saves her allowance and she is eventually able to buy her new scooter. And in the second video, you will see a group of friends that want to raise money to buy toys for other children in need. Videos https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxWBG5HwxlI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5eI5JvTGzAI Questions • What does SMART stand for? Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Rewarding, Time Specific • Create a long term and a short-term goal for yourself. Write them down on a piece of paper. Too Good for Drugs Session 2 Major Intersection-Decision Making In this session, we will talk about making decisions. How many decisions have you already made today? Some decisions require a lot of thought and some you just do. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

I Like Fruits and Veggies I Eat ‘Em Everyday to Keep My Body Healthy So I Can Learn and Play (Repeat)

1 Shine ‘Em Up! Words and Music by Terry Lupton & Steve Shepherd Performed by Keely Hawks with the Shepherd and Lang Kids I like fruits and veggies I eat ‘em everyday To keep my body healthy So I can learn and play (repeat) Growing in the sunshine Drinking up the rain It’s nature’s way of showing us Something we all share— But no two are the same! Chorus: Shine ‘em up Take a bite Satisfy your appetite Apples oranges anything you like Shine ‘em up[ Eat ‘em down Feel the energy Go round and round Like apples and oranges Mommy tosses salad And Daddy steams the rice My sister sets the table Big brother adds the spice We all sit down together The celebration starts We serve the five food groups And shine up every heart Growing up so big and strong I’ll eat my meats and grains But I love fruits and vegetables They’re crunchy and sweet— But no two are the same! Chorus (2X) Growing up so big and strong I’ll eat my meats and grains But I love fruits and vegetables They’re crunchy and sweet— But no two are the same! Chorus (2X) © 2004 TuneBoyMusic 2 (ASCAP) 2 Shine ‘Em Up! Suggestions for physical activity: Small groups of 6-8 dancers in circle formation step in place. Students may be standing behind desks or in open space. This is a routine to warm up body for more vigorous exercise. (Standard 3) One player in each group begins leading low impact movements in place. -

Cd Lyrics What Again

Lyrics for the CD What, AGAIN?! by Lou and Peter Berryman Recorded in 1993 All songs © L&P Berryman Words by Peter, Music by Lou 1 Squalor 2 Alice Hotel 3 Play It Again 4 Classified Rag 5 Crab Canape 6 Do You Think It's Gonna Rain 7 Naked & Nude 8 A Chat With Your Mother 9 When Did We Have Sauerkraut 10 It's Better Than That 11 John Ed Hammet 12 The February March 13 April May 14 Your State's Name Here 15 Why Am I Painting The Living Room Lou and Peter Berryman Box 3400 Madison WI 53704 LOUANDPETER.COM [email protected] [email protected] 1 SQUALOR ©1980 Lou & Peter Berryman In the squalor of her awful little shack she sat With her grungy cat and her parakeet With rats a-runnin' 'round the size of caribou Playing peek-a-boo with her filthy feet Eating donuts with a spoon and drinking Ovaltine Through a scum of green floating leisurely In a coffee cup of plastic from the Sally Ann Shaking in her hand, out of misery CHORUS: And it's all because she didn't eat her vegetables (X3) As a kid Or maybe didn't chew 'em properly, If she did Her brother slept behind the shack without a bed With his battered head resting on his knee As the roaches and the traffic sang a lullaby The water pipes would sigh a little harmony With the stogies he had found wrapped up in cellophane To keep out the rain when the night was through He would stumble down the alley pickin' junk sometimes Or try to beg for dimes on the avenue. -

When Dance Is About More Than Good Training, Everybody Wings

Upcoming Events - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Feb. Payments Due Feb. 1 When Dance is About More than Good Training, Competition Company Feb. 4-5 Rehearsals Everybody Wings Competition Company Feb. 18-19 Rehearsals Does Fusion Dance offer Instructors, parents, and helping them in other NUVO Convention Feb. 24-26 great dance training? Of volunteers and students ways. Mayo Civic Center course it does! However, if invest an enormous amount Rochester we only train dancers, don’t of time, energy and Older students are offered March Payments Due Mar. 1 commitment into dance opportunities to help in the Competition Company Mar. 4-5 we miss the point with most Rehearsals of our students? That is why because it really does add up classroom through Assistant Spring Break – Mar. 10-19 Fusion Dance strives to to more than just great Training Programs and may No Dance offer more than just great dancing. Students receive also become Teachers In Dance Resumes Mar. 20 dancing. many benefits from their Training and work one-on- Competition Company Mar. 25 Rehearsals involvement with dance, one with our experienced Competition Dress Mar. 26 Our instructors and staff do such as dedication, grace, instructors. Rehearsal not receive thank-you cards poise, perseverance, time First Competition Mar. 31- for pretty pliés or attractive management, organizational At every level of the dance Apr. 2 pirouettes. We receive skills, teamwork and work program, kids are being Apr. Payments Due Apr. 1 crayon drawings of smiling ethic. built up from the inside out Second Competition Apr. 7-9 dancers surrounded by pink through the magic of dance. -

Drake View Album Download Drake View Album Download

drake view album download Drake view album download. Drake Views Updated Download album, stream full hq songs | Pc mobile versions, download Drake Views Direct album. Drake's fourth album sounds claustrophobic and too long and weirdly monotonous, yet a few great moments are triggered by the occasional tweaks in the mix. On July 31, 2015, the track was recorded by Nineteen85 as the album's lead single "Hotline Bling" was released. 'Hotline Bling' was included as the bonus track on the record, despite the song being released as the official lead single for Views. VIEWS is the name of the record, but its viewpoint is distinctly singular. In a recent, toothless interview, Drake told Zane Lowe, differentiating VIEWS from his previous work, "This album, I'm very proud to say, is just, I feel like I told everyone how I really feel." This may sound like a ludicrous distinction, but it's appropriate, and it suggests why this album sounds more like a claustrophobic mindfuck than a communal catharsis. There's never any doubt that Drake is the star of his own show. Artist: Drake Album: Views (2016) Genre: Hip-Hop. Track list: 01. Keep the Family Close 02. 9 03. U With Me? 04. Feel No Ways 05. Hype 06. Weston Road Flows 07. Redemption 08. With You (feat. PARTYNEXTDOOR) 09. Faithful (feat. love-vendor C & dvsn) 10. Still Here 11. Controlla 12. One Dance (feat. Wizkid & Kyla) 13. Grammys (feat. Future) 14. Childs Play 15. Pop Style 16. Too Good (feat. Rihanna) 17. Summers Over Interlude 18. Fire & Desire 19.