The Science Citation Index“: a New Concept in Indexing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citation Analysis for the Modern Instructor: an Integrated Review of Emerging Research

CITATION ANALYSIS FOR THE MODERN INSTRUCTOR: AN INTEGRATED REVIEW OF EMERGING RESEARCH Chris Piotrowski University of West Florida USA Abstract While online instructors may be versed in conducting e-Research (Hung, 2012; Thelwall, 2009), today’s faculty are probably less familiarized with the rapidly advancing fields of bibliometrics and informetrics. One key feature of research in these areas is Citation Analysis, a rather intricate operational feature available in modern indexes such as Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO. This paper reviews the recent extant research on bibliometrics within the context of citation analysis. Particular focus is on empirical studies, review essays, and critical commentaries on citation-based metrics across interdisciplinary academic areas. Research that relates to the interface between citation analysis and applications in higher education is discussed. Some of the attributes and limitations of citation operations of contemporary databases that offer citation searching or cited reference data are presented. This review concludes that: a) citation-based results can vary largely and contingent on academic discipline or specialty area, b) databases, that offer citation options, rely on idiosyncratic methods, coverage, and transparency of functions, c) despite initial concerns, research from open access journals is being cited in traditional periodicals, and d) the field of bibliometrics is rather perplex with regard to functionality and research is advancing at an exponential pace. Based on these findings, online instructors would be well served to stay abreast of developments in the field. Keywords: Bibliometrics, informetrics, citation analysis, information technology, Open resource and electronic journals INTRODUCTION In an ever increasing manner, the educational field is irreparably linked to advances in information technology (Plomp, 2013). -

How Can Citation Impact in Bibliometrics Be Normalized?

RESEARCH ARTICLE How can citation impact in bibliometrics be normalized? A new approach combining citing-side normalization and citation percentiles an open access journal Lutz Bornmann Division for Science and Innovation Studies, Administrative Headquarters of the Max Planck Society, Hofgartenstr. 8, 80539 Munich, Germany Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/qss/article-pdf/1/4/1553/1871000/qss_a_00089.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 Keywords: bibliometrics, citation analysis, citation percentiles, citing-side normalization Citation: Bornmann, L. (2020). How can citation impact in bibliometrics be normalized? A new approach ABSTRACT combining citing-side normalization and citation percentiles. Quantitative Since the 1980s, many different methods have been proposed to field-normalize citations. In this Science Studies, 1(4), 1553–1569. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00089 study, an approach is introduced that combines two previously introduced methods: citing-side DOI: normalization and citation percentiles. The advantage of combining two methods is that their https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00089 advantages can be integrated in one solution. Based on citing-side normalization, each citation Received: 8 May 2020 is field weighted and, therefore, contextualized in its field. The most important advantage of Accepted: 30 July 2020 citing-side normalization is that it is not necessary to work with a specific field categorization scheme for the normalization procedure. The disadvantages of citing-side normalization—the Corresponding Author: Lutz Bornmann calculation is complex and the numbers are elusive—can be compensated for by calculating [email protected] percentiles based on weighted citations that result from citing-side normalization. On the one Handling Editor: hand, percentiles are easy to understand: They are the percentage of papers published in the Ludo Waltman same year with a lower citation impact. -

Research Performance of Top Universities in Karnataka: Based on Scopus Citation Index Kodanda Rama PES College of Engineering, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln September 2019 Research Performance of Top Universities in Karnataka: Based on Scopus Citation Index Kodanda Rama PES College of Engineering, [email protected] C. P. Ramasesh [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Scholarly Communication Commons, and the Scholarly Publishing Commons Rama, Kodanda and Ramasesh, C. P., "Research Performance of Top Universities in Karnataka: Based on Scopus Citation Index" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2889. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2889 Research Performance of Top Universities in Karnataka: Based on Scopus Citation Index 1 2 Kodandarama and C.P. Ramasesh ABSTRACT: [Paper furnishes the results of the analysis of citations of research papers covered by Scopus database of Elsevier, USA. The coverage of the database is complete; citations depicted by Scopus upto June 2019 are considered. Study projects the research performance of six well established top universities in the state of Karnataka with regard the number of research papers covered by scholarly journals and number of scholars who have cited these research papers. Also projected is the average citations per research paper and h-Index of authors. Paper also projects the performance of top faculty members who are involved in contributing research papers. Collaboration with authors of foreign countries in doing research work and publishing papers are also comprehended in the study, including the trends in publishing research papers which depict the decreasing and increasing trends of research work.] INTRODUCTION: Now-a-days, there is emphasis on improving the quality of research papers on the whole. -

In-Text Citation's Frequencies-Based Recommendations of Relevant

In-text citation's frequencies-based recommendations of relevant research papers Abdul Shahid1, Muhammad Tanvir Afzal2, Abdullah Alharbi3, Hanan Aljuaid4 and Shaha Al-Otaibi5 1 Institute of Computing, Kohat University of Science & Technology, Kohat, Pakistan 2 Department of Computer Science, NAMAL Institute, Mianwali, Pakistan 3 Department of Information Technology, College of Computers and Information Technology, Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia 4 Computer Sciences Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University (PNU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 5 Information Systems Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ABSTRACT From the past half of a century, identification of the relevant documents is deemed an active area of research due to the rapid increase of data on the web. The traditional models to retrieve relevant documents are based on bibliographic information such as Bibliographic coupling, Co-citations, and Direct citations. However, in the recent past, the scientific community has started to employ textual features to improve existing models' accuracy. In our previous study, we found that analysis of citations at a deep level (i.e., content level) can play a paramount role in finding more relevant documents than surface level (i.e., just bibliography details). We found that cited and citing papers have a high degree of relevancy when in-text citations frequency of the cited paper is more than five times in the citing paper's text. This paper is an extension of our previous study in terms of its evaluation of a comprehensive dataset. Moreover, the study results are also compared with other state-of-the-art approaches i.e., content, metadata, and bibliography. -

JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 3751

Journal Format For Print Page: ISI 页码,1/62 SCIENCE CITATION INDEX - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 3751 1. AAPG BULLETIN Monthly ISSN: 0149-1423 AMER ASSOC PETROLEUM GEOLOGIST, 1444 S BOULDER AVE, PO BOX 979, TULSA, USA, OK, 74119-3604 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences 2. ABDOMINAL IMAGING Bimonthly ISSN: 0942-8925 SPRINGER, 233 SPRING ST, NEW YORK, USA, NY, 10013 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. Current Contents - Clinical Medicine 4. BIOSIS Previews 3. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY Semiannual ISSN: 0065- 7727 AMER CHEMICAL SOC, 1155 16TH ST, NW, WASHINGTON, USA, DC, 20036 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. BIOSIS Previews 4. BIOSIS Reviews Reports And Meetings 4. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE Monthly ISSN: 1069-6563 WILEY-BLACKWELL, 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN, USA, NJ, 07030-5774 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. Current Contents - Clinical Medicine 5. ACADEMIC MEDICINE Monthly ISSN: 1040-2446 LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS, 530 WALNUT ST, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19106- 3621 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. Current Contents - Clinical Medicine 6. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH Monthly ISSN: 0001-4842 AMER CHEMICAL SOC, 1155 16TH ST, NW, WASHINGTON, USA, DC, 20036 1. Science Citation Index 2. Science Citation Index Expanded 3. Current Contents - Life Sciences 4. Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences 7. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL Bimonthly ISSN: 0889-325X AMER CONCRETE INST, 38800 COUNTRY CLUB DR, FARMINGTON HILLS, USA, MI, 48331 1. Science Citation Index 2. -

Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus

Journal of Informetrics, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1160-1177, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOI.2018.09.002 Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories Alberto Martín-Martín1 , Enrique Orduna-Malea2 , Mike 3 1 Thelwall , Emilio Delgado López-Cózar Version 1.6 March 12, 2019 Abstract Despite citation counts from Google Scholar (GS), Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus being widely consulted by researchers and sometimes used in research evaluations, there is no recent or systematic evidence about the differences between them. In response, this paper investigates 2,448,055 citations to 2,299 English-language highly-cited documents from 252 GS subject categories published in 2006, comparing GS, the WoS Core Collection, and Scopus. GS consistently found the largest percentage of citations across all areas (93%-96%), far ahead of Scopus (35%-77%) and WoS (27%-73%). GS found nearly all the WoS (95%) and Scopus (92%) citations. Most citations found only by GS were from non-journal sources (48%-65%), including theses, books, conference papers, and unpublished materials. Many were non-English (19%- 38%), and they tended to be much less cited than citing sources that were also in Scopus or WoS. Despite the many unique GS citing sources, Spearman correlations between citation counts in GS and WoS or Scopus are high (0.78-0.99). They are lower in the Humanities, and lower between GS and WoS than between GS and Scopus. The results suggest that in all areas GS citation data is essentially a superset of WoS and Scopus, with substantial extra coverage. -

Comparing Statistics from the Bibliometric Production Platforms Of

Comparing Bibliometric Statistics Obtained from the Web of Science and Scopus Éric Archambault Science-Metrix, 1335A avenue du Mont-Royal E., Montréal, Québec, H2J 1Y6, Canada and Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (OST), Centre interuniversitaire de recherche sur la science et la technologie (CIRST), Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal (Québec), Canada. E-mail: [email protected] David Campbell Science-Metrix, 1335A avenue du Mont-Royal E., Montréal, Québec, H2J 1Y6, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] Yves Gingras, Vincent Larivière Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (OST), Centre interuniversitaire de recherche sur la science et la technologie (CIRST), Université du Québec à Montréal, Case Postale 8888, succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal (Québec), H3C 3P8, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]; lariviere.vincent @uqam.ca Abstract For more than 40 years, the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI, now part of Thomson Reuters) produced the only available bibliographic databases from which bibliometricians could compile large- scale bibliometric indicators. ISI’s citation indexes, now regrouped under the Web of Science (WoS), were the major sources of bibliometric data until 2004, when Scopus was launched by the publisher Reed Elsevier. For those who perform bibliometric analyses and comparisons of countries or institutions, the existence of these two major databases raises the important question of the comparability and stability of statistics obtained from different data sources. This paper uses macro- level bibliometric indicators to compare results obtained from the WoS and Scopus. It shows that the correlations between the measures obtained with both databases for the number of papers and the number of citations received by countries, as well as for their ranks, are extremely high (R2 ≈ .99). -

The Journal Impact Factor Denominator Defining Citable (Counted) Items

COMMENTARIES The Journal Impact Factor Denominator Defining Citable (Counted) Items Marie E. McVeigh, MS The items counted in the denominator of the impact fac- tor are identifiable in the Web of Science database by hav- Stephen J. Mann ing the index field document type set as “Article,” “Re- view,” or “Proceedings Paper” (a specialized subset of the VER ITS 30-YEAR HISTORY, THE JOURNAL IMPACT article document type). These document types identify the factor has been the subject of much discussion scholarly contribution of the journal to the literature and and debate.1 From its first release in 1975, bib- are counted as “citable items” in the denominator of the im- liometricians and library scientists discussed its pact factor. A journal accepted for coverage in the Thom- Ovalue and its vagaries. In the last decade, discussion has 6 son Reuters citation database is reviewed by experts who shifted to the way in which impact factor data are used. In consider the bibliographic and bibliometric characteristics an environment eager for objective measures of productiv- of all article types published by that journal (eg, items), which ity, relevance, and research value, the impact factor has been are covered by that journal in the context of other materi- applied broadly and indiscriminately.2,3 The impact factor als in the journal, the subject, and the database as a whole. has gone from being a measure of a journal’s citation influ- This journal-specific analysis identifies the journal sec- ence in the broader literature to a surrogate that assesses tions, subsections, or both that contain materials likely to the scholarly value of work published in that journal. -

— Emerging Sources Citation Index

WEB OF SCIENCE™ CORE COLLECTION — EMERGING SOURCES CITATION INDEX THE VALUE OF COVERAGE IN INTRODUCING THE EMERGING SOURCES WEB OF SCIENCE CITATION INDEX This year, Clarivate Analytics is launching the Emerging INCREASING THE VISIBILITY OF Sources Citation Index (ESCI), which will extend the SCHOLARLY RESEARCH universe of publications in Web of Science to include With content from more than 12,700 top-tier high-quality, peer-reviewed publications of regional international and regional journals in the Science importance and in emerging scientific fields. ESCI will Citation Index Expanded™ (SCIE),the Social Sciences also make content important to funders, key opinion Citation Index® (SSCI), and the Arts & Humanities leaders, and evaluators visible in Web of Science Core Citation Index® (AHCI); more than 160,000 proceedings Collection even if it has not yet demonstrated citation in the Conference Proceedings Citation Index; and impact on an international audience. more than 68,000 books in the Book Citation Index; Journals in ESCI have passed an initial editorial Web of Science Core Collection sets the benchmark evaluation and can continue to be considered for for information on research across the sciences, social inclusion in products such as SCIE, SSCI, and AHCI, sciences, and arts and humanities. which have rigorous evaluation processes and selection Only Web of Science Core Collection indexes every paper criteria. All ESCI journals will be indexed according in the journals it covers and captures all contributing to the same data standards, including cover-to-cover institutions, no matter how many there are. To be indexing, cited reference indexing, subject category included for coverage in the flagship indexes in the assignment, and indexing all authors and addresses. -

Networks of Reader and Country Status: an Analysis of Mendeley Reader Statistics

Networks of reader and country status: an analysis of Mendeley reader statistics Robin Haunschild1, Lutz Bornmann2 and Loet LeydesdorV3 1 Information Retrieval Service, Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Stuttgart, Germany 2 Division for Science and Innovation Studies, Administrative Headquarters of the Max Planck Society, Munich, Germany 3 Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands ABSTRACT The number of papers published in journals indexed by the Web of Science core collection is steadily increasing. In recent years, nearly two million new papers were published each year; somewhat more than one million papers when primary research papers are considered only (articles and reviews are the document types where primary research is usually reported or reviewed). However, who reads these papers? More precisely, which groups of researchers from which (self-assigned) scientific disciplines and countries are reading these papers? Is it possible to visualize readership patterns for certain countries, scientific disciplines, or academic status groups? One popular method to answer these questions is a network analysis. In this study, we analyze Mendeley readership data of a set of 1,133,224 articles and 64,960 reviews with publication year 2012 to generate three diVerent networks: (1) The net- work based on disciplinary aYliations of Mendeley readers contains four groups: (i) biology, (ii) social sciences and humanities (including relevant computer sciences), (iii) bio-medical sciences, and (iv) natural sciences and engineering. In all four groups, the category with the addition “miscellaneous” prevails. (2) The network of co-readers in terms of professional status shows that a common interest in papers is mainly shared among PhD students, Master’s students, and postdocs. -

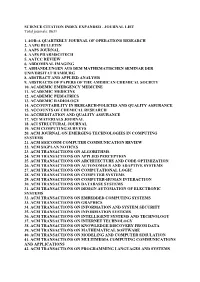

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Introduction to Bibliometrics

Introduction to Bibliometrics Bibliometrics A new service of the university library to support academic research Carolin Ahnert and Martin Bauschmann This work is licensed under: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Chemnitz ∙ 16.05.17 ∙ Carolin Ahnert, Martin Bauschmann www.tu-chemnitz.de Introduction to Bibliometrics What is bibliometrics? – short definition „Bibliometrics is the statistical analysis of bibliographic data, commonly focusing on citation analysis of research outputs and publications, i.e. how many times research outputs and publications are being cited“ (University of Leeds, 2014) Quantitative analysis and visualisation of scientific research output based on publication and citation data Chemnitz ∙ 16.05.17 ∙ Carolin Ahnert, Martin Bauschmann www.tu-chemnitz.de Introduction to Bibliometrics What is bibliometrics? – a general classification descriptive bibliometrics evaluative bibliometrics Identification of relevant research topics Evaluation of research performance cognition or thematic trends (groups of researchers, institutes, Identification of key actors universities, countries) interests Exploration of cooperation patterns and Assessment of publication venues communication structures (especially journals) Interdisciplinarity Productivity → visibility → impact → Internationality quality? examined Topical cluster constructs Research fronts/ knowledge bases Social network analysis: co-author, co- Indicators: number of articles, citation methods/ citation, co-word-networks etc. rate, h-Index,