Testimony Akl 070705.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS by MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS BY MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008 MANUFACTURER RECALLS VEHICLES ACCUBUIL T, INC 1 8 AM GENERAL CORPORATION 1 980 AMERICAN EAGLE MOTORCYCLE CO 1 14 AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR CO 8 212,212 AMERICAN SUNDIRO MOTORCYCLE 1 2,183 AMERICAN SUZUKI MOTOR CORP. 4 25,023 AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION CORP. 5 1,441 APRILIA USA INC. 2 409 ASTON MARTIN 2 666 ATHEY PRODUCTS CORP. 3 304 B. FOSTER & COMPANY, INC. 1 422 BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE 11 28,738 BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY 12 62,692 BUELL MOTORCYCLE CO 4 12,230 CABOT COACH BUILDERS, INC. 1 818 CARPENTER INDUSTRIES, INC. 2 6,838 CLASSIC LIMOUSINE 1 492 CLASSIC MANUFACTURING, INC. 1 8 COACHMEN INDUSTRIES, INC. 8 5,271 COACHMEN RV COMPANY 1 576 COLLINS BUS CORPORATION 1 286 COUNTRY COACH INC 6 519 CRANE CARRIER COMPANY 1 138 DABRYAN COACH BUILDERS 1 723 DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION 30 6,700,752 DAMON CORPORATION 3 824 DAVINCI COACHWORKS, INC 1 144 D'ELEGANT CONVERSIONS, INC. 1 34 DORSEY TRAILERS, INC. 1 210 DUTCHMEN MANUFACTURING, INC 1 105 ELDORADO NATIONAL 1 173 ELECTRIC TRANSIT, INC. 1 54 ELGIN SWEEPER COMPANY 1 40 E-ONE, INC. 1 3 EUROPA INTERNATIONAL, INC. 2 242 EXECUTIVE COACH BUILDERS 1 702 FEATHERLITE LUXURY COACHES 1 83 FEATHERLITE, INC. 2 3,235 FEDERAL COACH, LLC 1 230 FERRARI NORTH AMERICA 8 1,601 FLEETWOOD ENT., INC. 5 12, 119 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 60 7,485,466 FOREST RIVER, INC. 1 115 FORETRAVEL, INC. 3 478 FOURWINNS 2 2,276 FREIGHTLINER CORPORATION 27 233,032 FREIGHTLINER LLC 1 803 GENERAL MOTORS CORP. -

Separately Managed Account - MDT Tax Aware All Cap Core Portfolio Holdings As of 6/30/19

Separately Managed Account - MDT Tax Aware All Cap Core Portfolio Holdings as of 6/30/19 Sector Company COMMUNICATION SERVICES Alphabet Inc. CBS Corporation Charter Communications Inc * DISH Network Corporation Electronic Arts Inc. Facebook, Inc. Live Nation Entertainment, Inc. * MSG Networks Inc. Verizon Communications Inc. CONSUMER DISCRETIONARY Amazon.com, Inc. AutoZone, Inc. Burlington Stores, Inc. Expedia Group, Inc. Hilton Worldwide Holdings Kohl's Corporation Lowe's Companies, Inc. Lululemon Athletica Inc. Mohawk Industries, Inc. O'Reilly Automotive, Inc. Target Corporation The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company The Home Depot, Inc. Wyndham Destinations, Inc. CONSUMER STAPLES Archer-Daniels-Midland Company Church & Dwight Co., Inc. Costco Wholesale Corporation Herbalife Ltd. PepsiCo, Inc. The Estee Lauder Companies Inc. Walmart Inc. ENERGY Chevron Corporation * Continental Resources, Inc. EOG Resources, Inc. Exxon Mobil Corporation HollyFrontier Corporation Phillips 66 Valero Energy Corporation FINANCIALS Ameriprise Financial, Inc. Bank of America Corporation Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Capital One Financial Corporation Citigroup Inc. Everest Re Group, Ltd. First Republic Bank IntercontinentalExchange Inc. JPMorgan Chase & Co. M&T Bank Corporation Prudential Financial, Inc. The Allstate Corporation The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. The Progressive Corporation The Travelers Companies, Inc. HEALTH CARE Anthem, Inc. Biogen Idec Inc. Eli Lilly and Company Separately Managed Account - MDT Tax Aware All Cap Core Portfolio Holdings as of 6/30/19 Sector Company HCA Healthcare, Inc. * Humana Inc. Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Jazz Pharmaceuticals plc Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Stryker Corp * Veeva Systems Inc. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated INDUSTRIALS Caterpillar Inc. CSX Corporation Cummins Inc. Delta Air Lines, Inc. Lennox International Inc. Lockheed Martin Corporation * PACCAR Inc The Boeing Company Trinity Industries, Inc. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Progressive 2019 First Quarter Shareholders' Report

THE PROGRESSIVE CORPORATION 2019 First Quarter Report The Progressive Corporation and Subsidiaries Financial Highlights Three Months Ended March 31, Years Ended December 31, (billions - except per share amounts) 2019 2018 2018 2017 2016 2015 Net premiums written $ 9.2 $ 8.0 $ 32.6 $ 27.1 $ 23.4 $ 20.6 Growth over prior period 16% 23 % 20 % 16% 14% 10% Net premiums earned $ 8.5 $ 7.2 $ 30.9 $ 25.7 $ 22.5 $ 19.9 Growth over prior period 18% 19 % 20 % 14% 13% 8% Total revenues $ 9.3 $ 7.4 $ 32.0 $ 26.8 $ 23.4 $ 20.9 Net income attributable to Progressive $ 1.08 $ 0.72 $ 2.62 $ 1.59 $ 1.03 $ 1.27 Per common share $ 1.83 $ 1.22 $ 4.42 $ 2.72 $ 1.76 $ 2.15 Underwriting margin 11.2% 11.6 % 9.4 % 6.6% 4.9% 7.5% (billions - except shares outstanding, per share amounts, and policies in force) At Period-End Common shares outstanding (millions) 584.0 582.4 583.2 581.7 579.9 583.6 Book value per common share $ 19.89 $ 16.88 $ 17.71 $ 15.96 $ 13.72 $ 12.49 Consolidated shareholders' equity $ 12.1 $ 10.3 $ 10.8 $ 9.3 $ 8.0 $ 7.3 Common share close price $ 72.09 $ 60.93 $ 60.33 $ 56.32 $ 35.50 $ 31.80 Market capitalization $ 42.1 $ 35.5 $ 35.2 $ 32.8 $ 20.6 $ 18.6 Return on average common shareholders' equity Net income attributable to Progressive 27.1% 20.3 % 24.7 % 17.8% 13.2% 17.2% Comprehensive income attributable to Progressive 30.4% 21.0 % 23.8 % 21.7% 14.9% 14.2% Policies in force (thousands) Vehicle businesses: Personal Lines Agency - auto 6,609.1 5,909.1 6,358.3 5,670.7 5,045.4 4,737.1 Direct - auto 7,335.3 6,385.6 7,018.5 6,039.1 5,348.3 4,916.2 -

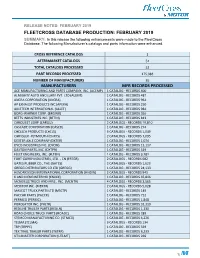

FLEETCROSS DATABASE PRODUCTION: FEBRUARY 2019 SUMMARY: in This Release the Following Enhancements Were Made to the Fleetcross Database

RELEASE NOTES: FEBRUARY 2019 FLEETCROSS DATABASE PRODUCTION: FEBRUARY 2019 SUMMARY: In this release the following enhancements were made to the FleetCross Database. The following Manufacturer’s catalogs and parts information were enhanced. CROSS REFERENCE CATALOGS 1 AFTERMARKET CATALOGS 51 TOTAL CATALOGS PROCESSED 52 PART RECORDS PROCESSED 175,983 NUMBER OF MANUFACTURERS 35 MANUFACTURERS MFR RECORDS PROCESSED ACE MANUFACTURING AND PARTS COMPANY, INC. (ACEMP) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 400 ALMIGHTY AUTO ANCILLARY PVT. LTD (ALLMT) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 487 ANCRA CORPORATION (ANCRA) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 964 AP EXHAUST PRODUCTS INC (APEXH) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 250 AXLETECH INTERNATIONAL (AXLET) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 984 BORG-WARNER CORP. (BRGWR) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 356 BETTS INDUSTRIES INC. (BTTIN) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 813 CARQUEST CORP (CARQU) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 19,810 CASCADE CORPORATION (CASCD) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 274 CHELSEA PRODUCTS (CHELS) 3 CATALOGS - RECORDS 1,049 CHRYSLER -PLYMOUTH (CHRYS) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 7,095 DEXTER AXLE COMPANY (DXTER) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 1,074 DYCO INDUSTRIES INC. (DYCIN) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 13,117 DAYTON PARTS, INC. (DYTPR) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 519 FLEET ENGINEERS, INC. (FLTEN) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 3,181 FORT GARRY INDUSTRIES, LTD. - CN (FRTGR) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 682 GATES RUBBER CO., THE (GATES) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 1,623 GREGG DISTRIBUTORS CO LTD (GREGG) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 24,133 HENDRICKSON INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION (HNDIN) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 943 K AND N ENGINEERING (KNXXX) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 35,846 MCNEILUS TRUCK AND MFG., INC. (MCNTR) 4 CATALOGS - RECORDS 3,565 MERITOR INC. (MERTR) 2 CATALOGS - RECORDS 5,028 MASCOT TRUCK PARTS LTD (MSCTP) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 149 PACCAR PARTS (PACCR) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 752 PERMCO (PERMC) 1 CATALOG - RECORDS 1,848 PUROLATOR INC. -

Whitelist Name Symbol

WHITELIST NAME SYMBOL 2U Inc TWOU 3M Company MMM 51JOB JOBS 58.com WUBA Abbott Laboratories ABT Abbvie ABBV Abiomed ABMD Acadia Healthcare ACHC Acorda Therapeutics ACOR Activision Blizzard ATVI Acuity Brands AYI Adaptive Biotechnologies ADPT Adobe ADBE Advance Auto Parts AAP Advanced Drainage Systems Inc WMS Advanced Micro Devices AMD AES AES Affiliated Managers Group AMG Aflac AFL AGCO Corporation AGCO Agilent Technologies A AGNC Investment AGNC Aimmune Therapeutics Inc AIMT Air Lease AL Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. APD Akamai Technologies AKAM Alarm.com Holdings Inc ALRM Alaska Air Group ALK Albemarle Corporation ALB Albertsons Companies ACI Alcoa AA Alexandria Real Estate ARE Alexion Pharmaceuticals ALXN Alibaba Group Holding BABA Align Technology ALGN Alleghany Corporation Y Allegheny Technologies ATI Alliance Data Systems ADS Alliant Energy LNT Allstate ALL Ally Financial ALLY Alnylam Pharmaceuticals ALNY Alphabet GOOGL Altice USA ATUS Altria Group MO AMAG Pharmaceuticals AMAG Amazon.com AMZN AMC Networks AMCX AMERCO UHAL Ameren AEE American Airlines Group AAL American Axle & Manufacturing Holdings AXL American Campus Communities ACC American Electric Power AEP American Express AXP American Financial Group AFG American International Group AIG American States Water Co AWR American Tower AMT American Water Works Company AWK American Well Corp AMWL AmeriGas Partners APU Ameriprise Financial AMP AmerisourceBergen ABC Ametek AME Amgen AMGN Amkor Technology AMKR Amphenol APH Amtrust Financial Services AFSI Anadarko Petroleum APC Analog -

April 24, 2020 the Honorable Michael R. Pence Vice President of the United States the White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

1000 Maine Avenue, SW, STE 500 Washington, DC 20024 202.872.1260 brt.org CHAIRMAN Doug McMillon April 24, 2020 Walmart PRESIDENT & CEO The Honorable Michael R. Pence Joshua Bolten Vice President of the United States Business Roundtable The White House BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Mary T. Barra Washington, DC 20500 General Motors Company Brenden Bechtel Dear Mr. Vice President, Bechtel Corporation Tim Cook As chief executives of many of the nation’s largest Apple Inc. businesses, Business Roundtable CEOs appreciate the Jamie Dimon complex roles that you and other leaders at all levels of JPMorgan Chase & Co. government play to address what may be the most Jim Fitterling significant public health and public policy challenges of our Dow lifetimes. We welcomed the criteria for reopening the U.S. economy issued by the Administration on April 16, as an Beth Ford Land O’Lakes, Inc. important step forward. In addition, we are pleased to see economic recovery planning taking shape across the United Lance Fritz Union Pacific Corporation States. Lynn J. Good Duke Energy Corporation Business Roundtable believes coordination is essential as we move forward and, accordingly, urges the federal Alex Gorsky government, states and local governments to develop Johnson & Johnson common approaches to protecting worker and customer Tricia Griffith safety. We have called for guidance from the Centers for Progressive Corporation Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on these issues. We Greg Hayes also are encouraging states to coordinate as they develop Raytheon Technologies Corporation plans for lifting restrictions, including through regional Marillyn A. Hewson groups. Given the imminent reopening to economic activity Lockheed Martin Corporation in some states, we believe a consistent and coordinated Jim Keane approach is urgently needed to create trust in resuming Steelcase Inc. -

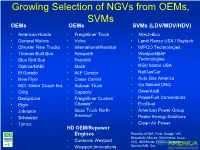

Growing Selection of Ngvs from Oems, Svms

Growing Selection of NGVs from OEMs, SVMs OEMs OEMs SVMs (LDV/MDV/HDV) • American Honda • Freightliner Truck • Altech-Eco • General Motors • Volvo • Landi Renzo USA / Baytech • Chrysler Ram Trucks • International/Navistar • IMPCO Technologies • Thomas Built Bus • Kenworth • Westport/BAF • Blue Bird Bus • Peterbilt Technologies • Optima/NABI • Mack • NGV Motori USA • El Dorado • ALF Condor • NatGasCar • New Flyer • Crane Carrier • Auto Gas America • MCI -Motor Coach Ind. • Autocar Truck • Go Natural CNG • Gillig • Capacity • Greenkraft • DesignLine • Freightliner Custom • PowerFuel Conversions • Elgin Chassis* • EcoDual • Johnston • Isuzu Truck North • American Power Group • Schwarze America* • Peake Energy Solutions • Tymco • Clean Air Power HD OEM/Repower Engines Retrofits of GM, Ford, Dodge, VW, Mitsubishi, Mazda, Workhorse, Isuzu, • Cummins Westport JAC, UtiliMaster, FCCC; Cummins, • Westport Innovations Daimler/MB, Cat., EPA Certification Requirements of NGVs • 1994: EPA sets certification requirements for CNG. – OEMs use of ECMs; concern about conversion emissions; – OEMs began complying to new standard; SVMs given alternative (Memo 1A Option 3). – Dozens of “kit manufacturers” leave market (“good”; quality/reliability was a mess) • April 2002: Option 3 phased out – SVMs must certify; very costly, technically difficult , requires expertise and $$$ equipment; further differentiated the quality engineered retrofit systems from “kits” • March 2011: EPA revised aftermarket certification rules – Relaxed rules apply primarily to vehicles -

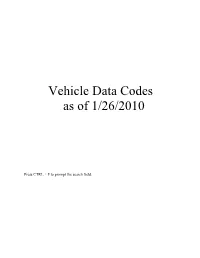

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

US Vegan Climate

US Vegan Climate ETF Schedule of Investments April 30, 2021 (Unaudited) Shares Security Description Value COMMON STOCKS - 99.4% Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services - 13.4% 1,675 Accenture plc - Class A $ 485,700 233 Allegion plc 31,311 107 Booking Holdings, Inc. (a) 263,870 293 Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc. 46,479 317 Equifax, Inc. 72,666 352 Expedia Group, Inc. 62,033 70 Fair Isaac Corporation (a) 36,499 729 Fidelity National Financial, Inc. 33,257 214 FleetCor Technologies, Inc. (a) 61,572 782 Global Payments, Inc. 167,841 961 IHS Markit, Ltd. 103,384 5,607 Mastercard, Inc. - Class A 2,142,210 425 Moody's Corporation 138,852 212 MSCI, Inc. 102,983 3,091 PayPal Holdings, Inc. (a) 810,738 491 TransUnion 51,354 8,745 Visa, Inc. - Class A 2,042,482 6,653,231 Construction - 0.9% 890 DR Horton, Inc. 87,478 1,956 Johnson Controls International plc 121,937 705 Lennar Corporation - Class A 73,038 19 NVR, Inc. (a) 95,344 682 PulteGroup, Inc. 40,320 396 Sunrun, Inc. (a) 19,404 437,521 Finance and Insurance - 14.1% 1,735 Aflac, Inc. 93,222 40 Alleghany Corporation (a) 27,159 797 Allstate Corporation 101,060 969 Ally Financial, Inc. 49,855 1,588 American Express Company 243,520 2,276 American International Group, Inc. 110,272 314 Ameriprise Financial, Inc. 81,138 657 Anthem, Inc. 249,259 596 Aon plc - Class A 149,858 1,025 Arch Capital Group, Ltd. (a) 40,703 496 Arthur J. -

Pax U.S. Sustainable Economy Fund USD 3/31/2021 Port. Ending Market

Pax U.S. Sustainable Economy Fund USD 6/30/2021 Port. Ending Market Value Portfolio Weight Apple Inc. 15,530,305.28 5.3 Microsoft Corporation 14,041,830.60 4.8 Alphabet Inc. Class A 10,121,219.55 3.4 NVIDIA Corporation 9,590,798.70 3.3 Johnson & Johnson 5,934,923.24 2.0 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. 5,795,351.36 2.0 Verizon Communications Inc. 5,558,848.36 1.9 Zoetis, Inc. Class A 5,444,693.76 1.9 Lam Research Corporation 5,088,474.00 1.7 Home Depot, Inc. 4,922,386.04 1.7 Allstate Corporation 4,825,888.68 1.6 Waste Management, Inc. 4,781,954.30 1.6 HCA Healthcare Inc 4,744,683.00 1.6 American Water Works Company, Inc. 4,447,575.28 1.5 MetLife, Inc. 4,297,110.30 1.5 Linde plc 4,189,637.20 1.4 Texas Instruments Incorporated 4,116,566.10 1.4 Mastercard Incorporated Class A 3,986,417.71 1.4 CBRE Group, Inc. Class A 3,818,242.74 1.3 Alphabet Inc. Class C 3,646,695.60 1.2 Unum Group 3,561,502.00 1.2 ViacomCBS Inc. Class B 3,376,078.40 1.2 Intel Corporation 3,364,301.78 1.1 Applied Materials, Inc. 3,234,331.20 1.1 Eli Lilly and Company 3,148,325.84 1.1 HubSpot, Inc. 3,110,559.36 1.1 PepsiCo, Inc. 3,073,638.48 1.0 Procter & Gamble Company 2,941,878.79 1.0 United Parcel Service, Inc. -

The Plan Sponsors Listed Below Have at Least One Application for The

The plan sponsors listed below have at least one application for the Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS) program in an "Approved" status for a plan year ending in 2008 as of October 6, 2008. The state listed for each sponsor is the state provided by the sponsor on the application for the subsidy. This state may, or may not, be where the majority of the plan sponsor's retirees reside or where the plan sponsor is headquartered. This list will be updated periodically. Plan Plan Sponsor Business Name Sponsor State "K" Line America, Inc. VA 1199 SEIU Greater New York Benefit Fund NY 1199 SEIU National Benefit Fund NY 3M Company MN 4th District IBEW Health Fund WV A&E Television Networks NY A. DUDA & SONS, INC. FL A. M. TODD GROUP, INC. MI A. SCHULMAN, INC OH A. T. Massey Coal Company, Inc. VA AAA EAST PENN PA AAI Corporation MD AARP DC ABB Inc. CT Abbott Laboratories IL Abbott Pharmaceuticals PR Ltd. PR Abitibi Consolidated Sales Corporation NY ABN AMRO NORTH AMERICA HOLDING COMPANY IL A-C RETIREES' VOLUNTARY BENFITS PLAN WI Acadia Parish School Board LA Accenture LLP IL Accuride Corporation IN ACF Industries LLC MO ACGME IL Acoustical Society of America NY Acton Health Insurance Trust MA Actuant Corporation WI Adirondack Central School NY Administrative Office of the Pennsylvania Courts PA Adventist Risk Management MD Advisory Services OH AEGON USA, Inc. IA AFG Industries, Inc. TN AFL-CIO Health and Welfare Trust DC AFSCME DC AFSCME Council 31 IL afscme d.c. 47 health & welfare fund PA AFSCME District Council 33 Health and Welfare Plan PA AFTRA Health Fund NY AGC-IUOE Local 701 Health & Welfare Trust Fund WA AGCO Corporation GA Agilent Technologies, Inc.