Open Dissertation-Final Submision-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMERIAN LITERATURE and SUMERIAN IDENTITY My Title Puts

CNI Publicati ons 43 SUMERIAN LITERATURE AND SUMERIAN IDENTITY JERROLD S. COOPER PROBLEMS OF C..\NONlCl'TY AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN A NCIENT EGYPT AND MESOPOTAMIA There is evidence of a regional identity in early Babylonia, but it does not seem to be of the Sumerian ethno-lingusitic sort. Sumerian Edited by identity as such appears only as an artifact of the scribal literary KIM RYHOLT curriculum once the Sumerian language had to be acquired through GOJKO B AR .I AMOVIC educati on rather than as a mother tongue. By the late second millennium, it appears there was no notion that a separate Sumerian ethno-lingui stic population had ever existed. My title puts Sumerian literature before Sumerian identity, and in so doing anticipates my conclusion, which will be that there was little or no Sumerian identity as such - in the sense of "We are all Sumerians!" outside of Sumerian literature and the scribal milieu that composed and transmitted it. By "Sumerian literature," I mean the corpus of compositions in Sumerian known from manuscripts that date primarily 1 to the first half of the 18 h century BC. With a few notable exceptions, the compositions themselves originated in the preceding three centuries, that is, in what Assyriologists call the Ur III and Isin-Larsa (or Early Old Babylonian) periods. I purposely eschew the too fraught and contested term "canon," preferring the very neutral "corpus" instead, while recognizing that because nearly all of our manuscripts were produced by students, the term "curriculum" is apt as well. 1 The geographic designation "Babylonia" is used here for the region to the south of present day Baghdad, the territory the ancients would have called "Sumer and Akkad." I will argue that there is indeed evidence for a 3rd millennium pan-Babylonian regional identity, but little or no evidence that it was bound to a Sumerian mother-tongue community. -

Possibilities of Restoring the Iraqi Marshes Known As the Garden of Eden

Water and Climate Change in the MENA-Region Adaptation, Mitigation,and Best Practices International Conference April 28-29, 2011 in Berlin, Germany POSSIBILITIES OF RESTORING THE IRAQI MARSHES KNOWN AS THE GARDEN OF EDEN N. Al-Ansari and S. Knutsson Dept. Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering, Lulea University, Sweden Abstract The Iraqi marsh lands, which are known as the Garden of Eden, cover an area about 15000- 20000 sq. km in the lower part of the Mesopotamian basin where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow. The marshes lie on a gently sloping plan which causes the two rivers to meander and split in branches forming the marshes and lakes. The marshes had developed after series of transgression and regression of the Gulf sea water. The marshes lie on the thick fluvial sediments carried by the rivers in the area. The area had played a prominent part in the history of man kind and was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Summarian more than 6000 BP. The area was considered among the largest wetlands in the world and the greatest in west Asia where it supports a diverse range of flora and fauna and human population of more than 500000 persons and is a major stopping point for migratory birds. The area was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Sumerians about 6000 years BP. It had been estimated that 60% of the fish consumed in Iraq comes from the marshes. In addition oil reserves had been discovered in and near the marshlands. The climate of the area is considered continental to subtropical. -

Camel Laboratory Investigates the Landscape

PAGE 6 NEWS & NOTES CAMEL LABORATORY INVESTIGATES THE LANDSCAPE OF ASSYRIA FROM SPACE JASON UR In 1932 the Oriental Institute excavated the city of Dur- research on Assyrian settlement, canals, and roads at the 49th Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), the capital of the Assyrian Em- annual meeting of the Rencontre Assyriologique International pire under King Sargon II (721–705 B.C.) and the original home at the British Museum in London, in a session organized by of the magnificent reliefs on display in the Museum’s new Tony Wilkinson, the founder of CAMEL. Yelda Khorsabad Court. During the excavation, a workman re- My own contribution was a reassessment of Jacobsen and layed stories of stone blocks inscribed with cuneiform writing Lloyd’s reconstruction of the course of Sennacherib’s canal. They had been limited to ground observation and testimony from local residents, but I have been able to use aerial photog- raphy and declassified American intelligence satellite imagery from the 1960s and early 1970s (the CORONA program) to map the traces in a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) computer program (fig. 2). In addition to the Jerwan canal, this research has identified and mapped over 60 km of other canals across a wide swath of Assyria (fig. 3), some of which had not been recognized on the ground before. The unexpected extent of Sennacherib’s canals must be understood within the context of his other actions. Upon the death of his father, he moved the capital to the newly ex- panded city of Nineveh. As known from the Bible and his own inscriptions, he was a very prolific deporter of conquered populations; many of them were settled in his new capital, but many others filled in the productive agricultural hinterland of Figure 1. -

Powpa Action-Plan-Republic of Iraq

Action Plan for Implementing the Programme of Work on Protected Areas of the Convention on Biological Diversity Iraq Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity [20 May 2012] Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point Dr. Ali Al-Lami, Ph.D.(Ecologist) Minister Advisor; Ministry of Environment of Iraq Email: [email protected] Lead implementing agency : Ministry of Environment of Iraq Multi-stakeholder committee : In Iraq there are several national Committees that were established to support the Government in developing policies, planning and reporting on different environmental fields. As for Protected areas, two national committees are relevant: - The National Committee for Protected Areas - Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee National Committee for Protected Areas A National Committee for Protected Areas was established in 2008 for planning and management of a network of Protected Areas in Iraq. This national inter-ministerial Committee is lead by the Ministry of Environment and is formed by the representatives of the following institutions: • Ministry of Environment (Leader) • Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research • Ministry of Water Resources • Ministry of Science & Technology • Ministry of Municipalities & Public Works • Ministry of State for Tourism & Antiquities • Ministry of Agriculture • Ministry of Education • NGO representative Nature Iraq Organization Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee (RAMSAR Convention) The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands was ratified by Iraq in October -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

REPORT & ACCOUNTS for the YEAR ENDED 31St MAY, Rg6g

BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ (Gertrude Bell Memorial) 31-34 GORDON SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.I * REPORT & ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31st MAY, rg6g * THE THmTY-SlXTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE SCHOOL W1LL BE HELD IN THE ROOMs oF THE BRITISH ACADE:M:Y, BuRLINGTON HousE, PICCADILLY, W.r, ON FRIDAY, 28th NO~ER, 1969, AT 5 p.m., TO HEAR MR. DAVID OATES; TO CONSIDER THE ACCOUNTS, THE BALANCE SHEET AND THE REPORTS OF THE COUNCIL AND THE AUDITOR; TO ELECT MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL; TO APPOINT AN AUDITOR; AND FOR ANY OTHER BUSINESS WHICH MAY PROPERLY DE TRANSACTED. BEFORE THE MEETING THERE WILL BE A :MEETING OF THE COUNCIL. ' COUNCIL PRESIDENT SIR JOHN TROUTBECK, G.B.E., K.C.M.G, LIFE MEMBERS *LADY RICHMOND SIR GEORGE TREVELYAN, BART. VICE-PRESIDENTS LADY MALLOW AN, C.B.E,, F.R.S.L., RON, D.LITT. (EXON.) *c, J• EDMONDS, C.M.G., C.B,E. T. E, EVANS, C.M.G., O.B.E. NOMINATED MEMBERS REPRESENTING RT. RON. THE LORD SALTER, P.O., G.B.E., K.C.B. *R. D, BARNETT, D.LITT., M.A., F.B,A., F.S.A. Society of Antiquaries *PROFESSOR 0. R. GURNEY, D. PHIL. Magdalen College, Oxford FOUNDERS MISS L, H. JEFFERY, M,A,, F.S,A. Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford THE LATE GERTRUDE BELL THE LATE SIR HUGH BELL, BART. MISS K, M, KENYON, C.B,E., M.A., D.LlT., F,B,A., F.S.A. THE LATE SIR CHARLES HYDE, BART. Board of Oriental Studies, Oxford University THE LATE SIR HENRY WELLCOME THE LATE MRS. -

Ecocide and Renewal in Iraq's Marshlands

Ending the Silence BY TOVA FLEMING & DR. MICHELLE ST EVEN S Photo of wild hogs in foreground and reed dwellings in the distance by Nik Wheeler Photo of wild hogs in foreground and reed dwellings the distance by Nik Ecocide and Renewal in Iraq’s Mashlands oisy fans carve paths of relief through the hot dominate the majority of images, women in black wail thick midsummer air of a classroom at the in grief, men scream into cameras, and children stare University of Barcelona. Small paper make- with eyes that appear much older than their years. shift fans flutter like migrating butterflies The intellectual blackout imposed by the Baathist re- Nacross the rows of tables as thirteen Iraqi scientists from gime, in combination with the Western media’s portray- the Basra Marine Science Center, University of Basra, al of the Middle East, obscures a vibrant and passionate Iraq, prepare to present their research on the Mesopota- people with a rich cultural and ecological history as well mian Marshes, Shatt al Arab River, and Gulf to a group as an ecological crisis of tragic proportions occurring of international peers who have convened at the World throughout the Tigris and Euphrates watersheds. The Congress for Middle Eastern Studies, July, 2010. media distortion also conceals the people trying to save This is the first time these scientists have had a chance the Tigris, Euphrates, and Mesopotamian Marshes. to present their research to an international audience. Surrounded by desert to the west and south, the Tigris “Scientists in Iraq have been living in a blackout for thir- and Euphrates Rivers bring life to the Mesopotamian re- ty years because of the gion, and an abundance dictatorship. -

The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities

Third State of Conservation Report Addressed by the Republic of Iraq to the World Heritage Committee on The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities World Heritage Property n. 1481 November 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. Requests by the World Heritage Committee 2. Cultural heritage 3. Natural heritage 4. Integrated management plan 5. Tourism plan 6. Engaging local communities in matters related to water use 7. World heritage centre/icomos/iucn reactive monitoring mission to the property 8. Planed construction projects 9. Survey the birds of prey coming in the marshes 10. Signature of the concerned authority 11. Annexes 2 1- REQUESTS BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE This report addresses the following requests expressed by World Heritage Committee in its Decision 43 COM 7B.35 (paragraphs 119 – 120), namely: 3. Welcomes the start of conservation work by international archaeological missions at the three cultural components of the property, Ur, Tell Eridu and Uruk, and, the comprehensive survey undertaken at Tell Eridu; 4. Regrets that no progress has been reported on the development of site-specific conservation plans for the three cultural components of the property, as requested by the Committee in response to the significant threats they face related to instability, significant weathering, inappropriate previous interventions, and the lack of continuous maintenance; 5. Urges the State Party to extend the comprehensive survey and mapping to all three cultural components of the property, as baseline data for future work, and to develop operational conservation plans for each as a matter of priority, and to submit these to the World Heritage Centre for review by the Advisory Bodies; 6. -

Mesopotamian Mooring Places, Elamite Garrisons and Aramean Settlements

Iranica Antiqua, vol. LIV, 2019 doi: 10.2143/IA.54.0.3287446 THE HARBOUR(S) OF NAGITU: MESOPOTAMIAN MOORING PLACES, ELAMITE GARRISONS AND ARAMEAN SETTLEMENTS BY Elynn GORRIS1 (Université catholique de Louvain) Abstract: This article investigates the toponym(s) Nagitu. In the Neo-Assyrian sources, the Elamite coastal town is often attested with various postpositions: Nagitu-raqqi, Nagitu-di’bina or Nagitu-of-Elam (ša KUR.ELAM.MA.KI). After an examination of the etymology of the various Nagitu attestations, geographical indications are sought to help determine the locations of the different Nagitu toponyms. These indications are then compared with the landscape descriptions of the Classical authors and the early Arab geographers in order to draw a picture of the historical geography of the Nagitu triad. Keywords: Nagitu, Elamite harbours, northern Persian coastline, historical geo- graphy Introduction The ancient maritime network of the Persian Gulf speaks to the imagina- tion. Each of the numerous elements enabling this network – the maritime itineraries, the harbours and mooring places, the types of seafaring ships, the variety of transported goods, the commercial and political interests of the kingdoms along the Gulf coast – warrants a historical study. But some are more amenable to scholarly research than others, depending on the available source material (cuneiform texts, archaeological remains, icono- graphy and paleogeography). One poorly investigated aspect of the Persian Gulf history is the histori- cal geography of the Elamite coastal region. In particular, the Neo-Elamite participation in the Gulf network during the first half of the 1st millennium 1 I would like to express my gratitude to Jean-Charles Ducène and Johannes den Heijer for navigating me through the literature on the Arab geographers. -

SENNACHERIB's AQUEDUCT at JERWAN Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS JAMES HENRY BREASTED Editor THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN Associate Editor oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu SENNACHERIB'S AQUEDUCT AT JERWAN oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA TOKYO, OSAKA, KYOTO, FUKUOKA, SENDAI THE COMMERCIAL PRESS, LIMITED SHANGHAI oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu 4~ -d~ Royal Air Force Official Crown Copyrighl Reored THE JERWAN AQUEDUCT. AnB VIEW oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIENTAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS VOLUME XXIV SENNACHERIB'S AQUEDUCT AT JERWAN By THORKILD JACOBSEN and SETON LLOYD WITH A PREFACE BY HENRI FRANKFORT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1035 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHIED MAY 1935 COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITr OF CHICAGO PRE8S CHICAGO,ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE It so happens that the first final publication of work undertaken by the Iraq Expedition refers neither to one of the sites for which the Oriental Institute holds a somewhat permanent concession nor to a task carried out by the expedition as a whole. The aqueduct at Jerwan- identified by Dr. Jacobsen at the end of the 1931/32 season-was explored by the two authors of this volume in March and April, 1933, on the strength of a sounding permit of four weeks' validity. Mrs. Rigmor Jacobsen was responsible for the photography. It was only by dint of a sustained and strenuous effort that the excavation was completed within the stipulated period. -

Sargon of Akkade and His God

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 69 (1), 63–82 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4 SARGON OF AKKADE AND HIS GOD COMMENTS ON THE WORSHIP OF THE GOD OF THE FATHER AMONG THE ANCIENT SEMITES STEFAN NOWICKI Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies, University of Wrocław ul. Szewska 49, 50-139 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The expression “god of the father(s)” is mentioned in textual sources from the whole area of the Fertile Crescent, between the third and first millennium B.C. The god of the fathers – aside from assumptions of the tutelary deity as a god of ancestors or a god who is a deified ancestor – was situated in the centre and the very core of religious life among all peoples that lived in the ancient Near East. This paper is focused on the importance of the cult of Ilaba in the royal families of the ancient Near East. It also investigates the possible source and route of spreading of the cult of Ilaba, which could have been created in southern Mesopotamia, then brought to other areas. Hypotheti- cally, it might have come to the Near East from the upper Euphrates. Key words: religion, Ilaba, royal inscriptions, Sargon of Akkade, god of the father, tutelary deity, personal god. The main aim of this study is to trace and describe the worship of a “god of the fa- ther”, known in Akkadian sources under the name of Ilaba, and his place in the reli- gious life of the ancient peoples belonging to the Semitic cultural circle. -

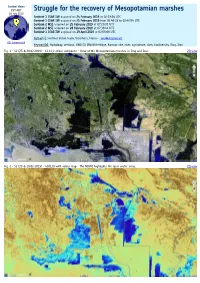

Struggle for the Recovery of Mesopotamian Marshes

Sentinel Vision EVT-487 Struggle for the recovery of Mesopotamian marshes 18 July 2019 Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 24 February 2019 at 02:53:54 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 25 February 2019 from 02:46:29 to 02:46:54 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 25 February 2019 at 07:29:01 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 28 February 2019 at 07:38:41 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 April 2019 at 02:55:08 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Hydrology, wetland, UNESCO World Heritage, Ramsar site, river, agriculture, dam, biodiversity, Iraq, Iran Fig. 1 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - 12,11,2 colour composite - View of the Mesopotamian marshes in Iraq and Iran. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - ndi(3,8) with colour map - The NDWI highlights the open water areas. 2D view The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) describes the Tigris-Euphrates alluvial salt marsh as follows: "The vast deltaic plain of the Euphrates, Tigris and Karun rivers is located at the northern end of the Persian Gulf, in extreme eastern Iraq and southwestern Iran. This alluvial basin drains a large area of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and the western Zagros Mountains of Iran, and the basin is covered in recent (Pleistocene and Holocene) alluvial sediments." Fig. 3 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - ndi(8,4) with colour map - The NDVI shows little healthy vegetation has recolonised the marshes yet. 2D view "The ecoregion is a complex of shallow freshwater lakes, swamps, marshes, and seasonally inundated plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.