Mesopotamian Mooring Places, Elamite Garrisons and Aramean Settlements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possibilities of Restoring the Iraqi Marshes Known As the Garden of Eden

Water and Climate Change in the MENA-Region Adaptation, Mitigation,and Best Practices International Conference April 28-29, 2011 in Berlin, Germany POSSIBILITIES OF RESTORING THE IRAQI MARSHES KNOWN AS THE GARDEN OF EDEN N. Al-Ansari and S. Knutsson Dept. Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering, Lulea University, Sweden Abstract The Iraqi marsh lands, which are known as the Garden of Eden, cover an area about 15000- 20000 sq. km in the lower part of the Mesopotamian basin where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow. The marshes lie on a gently sloping plan which causes the two rivers to meander and split in branches forming the marshes and lakes. The marshes had developed after series of transgression and regression of the Gulf sea water. The marshes lie on the thick fluvial sediments carried by the rivers in the area. The area had played a prominent part in the history of man kind and was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Summarian more than 6000 BP. The area was considered among the largest wetlands in the world and the greatest in west Asia where it supports a diverse range of flora and fauna and human population of more than 500000 persons and is a major stopping point for migratory birds. The area was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Sumerians about 6000 years BP. It had been estimated that 60% of the fish consumed in Iraq comes from the marshes. In addition oil reserves had been discovered in and near the marshlands. The climate of the area is considered continental to subtropical. -

Powpa Action-Plan-Republic of Iraq

Action Plan for Implementing the Programme of Work on Protected Areas of the Convention on Biological Diversity Iraq Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity [20 May 2012] Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point Dr. Ali Al-Lami, Ph.D.(Ecologist) Minister Advisor; Ministry of Environment of Iraq Email: [email protected] Lead implementing agency : Ministry of Environment of Iraq Multi-stakeholder committee : In Iraq there are several national Committees that were established to support the Government in developing policies, planning and reporting on different environmental fields. As for Protected areas, two national committees are relevant: - The National Committee for Protected Areas - Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee National Committee for Protected Areas A National Committee for Protected Areas was established in 2008 for planning and management of a network of Protected Areas in Iraq. This national inter-ministerial Committee is lead by the Ministry of Environment and is formed by the representatives of the following institutions: • Ministry of Environment (Leader) • Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research • Ministry of Water Resources • Ministry of Science & Technology • Ministry of Municipalities & Public Works • Ministry of State for Tourism & Antiquities • Ministry of Agriculture • Ministry of Education • NGO representative Nature Iraq Organization Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee (RAMSAR Convention) The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands was ratified by Iraq in October -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

Ecocide and Renewal in Iraq's Marshlands

Ending the Silence BY TOVA FLEMING & DR. MICHELLE ST EVEN S Photo of wild hogs in foreground and reed dwellings in the distance by Nik Wheeler Photo of wild hogs in foreground and reed dwellings the distance by Nik Ecocide and Renewal in Iraq’s Mashlands oisy fans carve paths of relief through the hot dominate the majority of images, women in black wail thick midsummer air of a classroom at the in grief, men scream into cameras, and children stare University of Barcelona. Small paper make- with eyes that appear much older than their years. shift fans flutter like migrating butterflies The intellectual blackout imposed by the Baathist re- Nacross the rows of tables as thirteen Iraqi scientists from gime, in combination with the Western media’s portray- the Basra Marine Science Center, University of Basra, al of the Middle East, obscures a vibrant and passionate Iraq, prepare to present their research on the Mesopota- people with a rich cultural and ecological history as well mian Marshes, Shatt al Arab River, and Gulf to a group as an ecological crisis of tragic proportions occurring of international peers who have convened at the World throughout the Tigris and Euphrates watersheds. The Congress for Middle Eastern Studies, July, 2010. media distortion also conceals the people trying to save This is the first time these scientists have had a chance the Tigris, Euphrates, and Mesopotamian Marshes. to present their research to an international audience. Surrounded by desert to the west and south, the Tigris “Scientists in Iraq have been living in a blackout for thir- and Euphrates Rivers bring life to the Mesopotamian re- ty years because of the gion, and an abundance dictatorship. -

The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities

Third State of Conservation Report Addressed by the Republic of Iraq to the World Heritage Committee on The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities World Heritage Property n. 1481 November 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. Requests by the World Heritage Committee 2. Cultural heritage 3. Natural heritage 4. Integrated management plan 5. Tourism plan 6. Engaging local communities in matters related to water use 7. World heritage centre/icomos/iucn reactive monitoring mission to the property 8. Planed construction projects 9. Survey the birds of prey coming in the marshes 10. Signature of the concerned authority 11. Annexes 2 1- REQUESTS BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE This report addresses the following requests expressed by World Heritage Committee in its Decision 43 COM 7B.35 (paragraphs 119 – 120), namely: 3. Welcomes the start of conservation work by international archaeological missions at the three cultural components of the property, Ur, Tell Eridu and Uruk, and, the comprehensive survey undertaken at Tell Eridu; 4. Regrets that no progress has been reported on the development of site-specific conservation plans for the three cultural components of the property, as requested by the Committee in response to the significant threats they face related to instability, significant weathering, inappropriate previous interventions, and the lack of continuous maintenance; 5. Urges the State Party to extend the comprehensive survey and mapping to all three cultural components of the property, as baseline data for future work, and to develop operational conservation plans for each as a matter of priority, and to submit these to the World Heritage Centre for review by the Advisory Bodies; 6. -

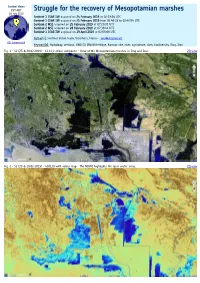

Struggle for the Recovery of Mesopotamian Marshes

Sentinel Vision EVT-487 Struggle for the recovery of Mesopotamian marshes 18 July 2019 Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 24 February 2019 at 02:53:54 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 25 February 2019 from 02:46:29 to 02:46:54 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 25 February 2019 at 07:29:01 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 28 February 2019 at 07:38:41 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 19 April 2019 at 02:55:08 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Hydrology, wetland, UNESCO World Heritage, Ramsar site, river, agriculture, dam, biodiversity, Iraq, Iran Fig. 1 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - 12,11,2 colour composite - View of the Mesopotamian marshes in Iraq and Iran. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - ndi(3,8) with colour map - The NDWI highlights the open water areas. 2D view The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) describes the Tigris-Euphrates alluvial salt marsh as follows: "The vast deltaic plain of the Euphrates, Tigris and Karun rivers is located at the northern end of the Persian Gulf, in extreme eastern Iraq and southwestern Iran. This alluvial basin drains a large area of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and the western Zagros Mountains of Iran, and the basin is covered in recent (Pleistocene and Holocene) alluvial sediments." Fig. 3 - S2 (25 & 28.02.2019) - ndi(8,4) with colour map - The NDVI shows little healthy vegetation has recolonised the marshes yet. 2D view "The ecoregion is a complex of shallow freshwater lakes, swamps, marshes, and seasonally inundated plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. -

65 Re Extrapolation for the Iraq Marshes Which Falling Within The

Re Extrapolation For The Iraq Marshes Which Falling Within The World Heritage List (A Literature Review) Kadhim J.L. Al- Zaidy 1, Giuliana Parisi 2 1 Department of Agri-Food Production and Environmental Sciences, Animal Sciences Section, Università di Firenze, Via delle Cascine 5, Florence 50144, Italy; 2 Department of Agri-Food Production and Environmental Sciences, Animal Sciences Section, Università di Firenze, Via delle Cascine 5, Florence 50144, Italy; Submission Track Abstract Received : 9/7/2017 The Mesopotamian Marshlands or The Garden of Eden, lies in the 2 Final Revision :19/7/2017 southern part of Iraq with estimated area of 15000-20000 km . Keywords Historically, the area had pioneering role in the human civilization Iraq, Mesopotamia, Cultural for over 5000 years. The indigenous people of the area are called ―Marsh Arabs‖ or ―Ma‘dan‖ who are the descendants of the Heritage, Biological Diversity, Sumerians and Semitic people. The former Iraqi regime (Saddam Invasive Species. Hussein) had violently led an aggressive campaign to drain the Corresponding marshes in 1991. Only %7 of the total area survived this campaign, giuliana.parisi@unifi.it which caused a mass destruction of the ecosystem and dwellers‘ [email protected] displacement. In 2003, water started to flow back to the area. Yet, the reflooding did not restore the whole former area of the wetlands. Moreover, the new ecosystem influenced the diversity and characteristics of the co-existing species in the area. In 2016, due to the importance of the Mesopotamian Marshlands, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed three marshes from the area as World Heritage Sites requiring conservation, namely: Hammar, Hwezeh and Central Marshes. -

The World Heritage Nomination of the Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities

The World Heritage Nomination of The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities A Case Study of Providing Upstream Guidance and Capacity Building for a World Heritage Nomination to a State Party to the 1972 Convention Géraldine Chatelard and Tarek Abulhawa Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain The World Heritage Nomination of The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of The geographical entities designation in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ARC-WH concerning the legal the Mesopotamian Cities status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of ARC-WH. A Case Study of Providing Upstream Guidance and Capacity Building for a World Heritage Nomination to a State Party to the 1972 Convention This publication has been made possible in part by ARC-WH, and it partners UNEP, IUCN, UNESCO Iraq Office and Ministry of Environment of Iraq and Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Géraldine Chatelard and Tarek Abulhawa provided significant in-kind contributions. Copyright: ©2015 Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage. Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

Restoring the Garden of Eden, Iraq -.: Scientific Press International Limited

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 2, no. 1, 2012, 53-88 ISSN: 1792-9040(print), 1792-9660 (online) International Scientific Press, 2012 Restoring the Garden of Eden, Iraq Nadhir Al-Ansari1, Sven Knutsson2 and Ammar A. Ali3 Abstract The Iraqi marsh lands, which are known as the Garden of Eden, cover an area about 15-20 103 km2 in the lower part of the Mesopotamian basin. The area had played a prominent part in the history of mankind and was inhabited since the dawn of civilization. The Iraqi government started to drain the marshes for political and military reasons and at 2000 less than 10% of the marshes remained. After 2003, the process of restoration and rehabilitation of Iraqi marshes started. There are number of difficulties encountered in the process. In this research we would like to explore the possibilities of restoring the Iraqi marshes. It is believed that 70- 75% of the original areas of the marshes can be restored. This implies that 13km3 water should be available to achieve this goal keeping the water quality as it is. To evaluate the water quality in the marshes, 154 samples were collected at 48 stations during summer, spring and winter. All the results indicate that the water quality was bad. To improve the water quality, then 18.86 km3 of water is required. This requires plenty of efforts and international cooperation to overcome the existing obstacles. 1 Lulea University of Technology, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Lulea University of Technology, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Lulea University of Technology, e-mail: [email protected] Article Info: Revised : February 24, 2012 . -

“Restoration of the Southern Iraqi Marshes”

STUART M. LEIDERMAN <[email protected]> COLLEGE-LEVEL ONLINE COURSE (3 credits) “Restoration of the Southern Iraqi Marshes” -- a challenging, contemporary and informative course on a world-class “hot topic” -- brings the front lines and the environmental realities of Iraq to your desktop -- puts you in touch with concerned scientists, engineers, students and journalists -- lets you examine, compare and critique actual documents and restoration plans -- helps you understand and appreciate the value of the world’s large wetlands What Students Say: “I really enjoyed this class. It was my favorite that I have taken at ISU.” “I have really enjoyed this class. The subject matter and the format have been very informative, engaging and even inspiring.” “...thank you for the information I gained from this course. I've considered wetland restoration courses before, and work in that area as well, but have not yet made that move. I learned enough in your class to answer most of my questions in that regard and I'll certainly be more actively involved in this in the future.” Syllabus available from instructor: Mr. Stuart M. Leiderman <[email protected]> 1 Stuart M. Leiderman, Environmental Response “Environmental Refugees and Ecological Restoration” P.O. Box 382, Durham, New Hampshire 03824 USA 603.776.0055 [email protected] Sample Syllabus for 3-Credit, College-Level Online Course: “RESTORING THE MARSHLANDS OF SOUTHERN IRAQ” PART I: THE PAST: 3000 B.C. - 2002 Preconceptions; Speeches in Parliament; Human and Environmental Dimensions; -

Changes in Mesopotamian Wetlands: Investigations Using Diverse Remote Sensing Datasets

Changes in Mesopotamian Wetlands: Investigations Using Diverse Remote Sensing Datasets Ali K. M. Al-Nasrawi University of Wollongong Ignacio Fuentes ( [email protected] ) The University of Sydney https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7066-7482 Dhahi Al-Shammari The University of Sydney Research Article Keywords: Ecosystem disturbance, remote sensing, wetlands, marshes, ancient civilizations Posted Date: February 8th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-165486/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Changes in Mesopotamian wetlands: Investigations using diverse remote sensing 2 datasets 3 Ali K. M. Al-Nasrawiac, Ignacio Fuentesb* and Dhahi Al-Shammarib 4 aSchool of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Science, University of Wollongong, Wollongong NSW 2522, 5 Australia. 6 bSchool of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney NSW 2000, Australia 7 cDepartment of Geography, University of Babylon, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific 8 Research, Hillah - Babylon, Iraq 9 10 Corresponding author: Ignacio Fuentes ([email protected]) 11 12 Abstract 13 Early civilizations have inhabited stable-water-resourced areas that supported living needs and activities, 14 including agriculture. The Mesopotamian marshes, recognised as the most ancient human-inhabited area 15 (~6000 years ago) and refuge of rich biodiversity, have experienced dramatic changes during the past five 16 decades, starting to fail in providing adequate environmental functioning and support of social communities 17 as they used to for thousands of years. The aim of this study is to observe, analyse and report the extent of 18 changes in these marshes from 1972 to 2020. -

Open Dissertation-Final Submision-2

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts RECONSTRUCTING THE RURAL ECONOMY OF SOUTHERN MESOPOTAMIA DURING THE THIRD MILLENNIUM B.C. A Dissertation in Anthropology by Zaid Alrawi © 2018 Zaid Alrawi Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Zaid Alrawi was reviewed and approved by the following: José M. Capriles Assistant Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee David Webster Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Kirk French Associate Teaching Professor of Anthropology Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Departments of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, and History Head of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies George Chaplin Special Member Senior Research Associate of Anthropology Douglas J. Kennett Department Head and Professor of Anthropology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation addresses the rural economy of southern Mesopotamia during the Third Millennium B.C. Previous research suggested that during the Early Dynastic, the region was characterized by a largely dispersed and decentralized settlement system that progressively became increasingly centralized with the emergence of the Akhadian Empire and the subsequent Ur III State. Our knowledge about the economic organization of rural Sumer, however, is largely based on ancient textual evidence, which is biased toward the perspective of city-based administrators. Focusing on the Girsu peripheral region of southern Mesopotamia, I explore landscape management, craft production, and exchange. I constructed a geographic information system including remote sensing images, field observations, published archaeological maps, and ancient textual evidence to explore the nature of settlement patterns and their change over time.