The Case for a Regional List Proportional Representation (PR) System for Ontario1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

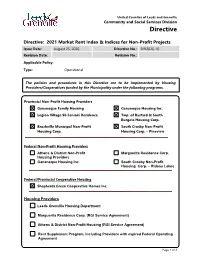

2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects

United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: Applicable Policy: Type: Operational The policies and procedures in this Directive are to be implemented by Housing Providers/Cooperatives funded by the Municipality under the following programs. Provincial Non-Profit Housing Providers Gananoque Family Housing Gananoque Housing Inc. Legion Village 96 Seniors Residence Twp. of Bastard & South Burgess Housing Corp. Brockville Municipal Non-Profit South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. Housing Corp. – Pineview Federal Non-Profit Housing Providers Athens & District Non-Profit Marguerita Residence Corp. Housing Providers Gananoque Housing Inc. South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. – Rideau Lakes Federal/Provincial Cooperative Housing Shepherds Green Cooperative Homes Inc. Housing Providers Leeds Grenville Housing Department Marguerita Residence Corp. (RGI Service Agreement) Athens & District Non-Profit Housing (RGI Service Agreement) Rent Supplement Program, including Providers with expired Federal Operating Agreement Page 1 of 3 United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: BACKGROUND Each year, the Ministry provides indices for costs and revenues to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act (HSA). The indices to be used for 2021 are contained in this directive. PURPOSE The purpose of this directive is to advise housing providers of the index factors to be used in the calculation of subsidy for 2021. ACTION TO BE TAKEN Housing providers shall use the index factors in the table below to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act, 2011 (HSA) on an annual basis. -

DIRECTORY Répertoire 2018 TABLE of CONTENTS Table Des Matières

CRAWFORD DIRECTORY Répertoire 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table des Matières 3 EXECUTIVE CONTACTS Contacts exécutifs 4 National Claims Management Centre (NCMC) Contacts Centre de Gestion de Réclamations National, Contrats 6 Global Technical Services (GTS®) Contacts Services Techniques Mondiaux, Contrats 8 Contractor Connection® Contacts Connection Contracteur, Contrats 10 ALBERTA 13 BRITISH COLUMBIA Colombie-Britannique 16 MANITOBA 17 NEW BRUNSWICK Nouveau-Brunswick 19 NEWFOUNDLAND & LABRADOR Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador 20 NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Territoires du Nord-Ouest 21 NOVA SCOTIA Nouvelle-Écosse 24 ONTARIO 40 PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard 41 QUÉBEC 45 SASKATCHEWAN EXECUTIVE CONTACTS CONTACTS EXECUTIVE EXECUTIVE CONTACTS Contacts exécutifs Pat Van Bakel, Heather Matthews President and CEO, Senior Vice President, Crawford & Company (Canada) Inc. National Claims Management Centre Président et chef de la direction Vice-présidente senior, centre national Crawford & Compagnie (Canada) inc. de gestion des réclamations Contacts exécutifs 55 University Avenue, Suite 400 539 Riverbend Dr. P.O. Box 36 Kitchener, ON N2K 3S3 Toronto, ON, M5J 2H7 Tel: 519 578 5540 x2672 Tel: 416 957 5003 Fax: 519 578 2868 [email protected] [email protected] Jim Eso Greg Smith Senior Vice President, Senior Vice President, Property & Casualty Administration Vice-président senior et Expert en Vice-président senior de dommages direct et accidents l’administration 539 Riverbend Dr. 55 University Avenue, Suite 400 Kitchener, ON N2K 3S3 P.O. Box 36 Tel: 519 578 5540 x2681 Toronto, ON, M5J 2H7 Fax: 519 578 2868 Tel: 416 957 5012 [email protected] Fax: 416 364 1641 [email protected] Gary Gardner Senior Vice President, Global Client Development Vice-président senior, Développement clients international 55 University Avenue, Suite 400 P.O. -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY 2013 STATISTICS In free and open societies, governments must be accessible and transparent to their citizens. TABLE OF CONTENTS Requests by the Public ...................................... 1 Provincial Compliance ..................................... 3 Municipal Compliance ................................... 12 Appeals .............................................................. 26 Privacy Complaints .......................................... 38 Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) .................................. 41 As I look back on the past years of the IPC, I feel that Ontarians can be assured that this office has grown into a first-class agency, known around the world for demonstrating innovation and leadership, in the fields of both access and privacy. STATISTICS 4 1 REQUESTS BY THE PUBLIC UNDER FIPPA/MFIPPA There were 55,760 freedom of information (FOI) requests filed across Ontario in 2013, nearly a 6% increase over 2012 where 52,831 were filed TOTAL FOI REQUESTS FILED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,995 17,334 34,329 Provincial 7,029 14,402 21,431 Total 24,024 31,736 55,760 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,726 17,304 34,030 Provincial 6,825 13,996 20,821 Total 23,551 31,300 54,851 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY SOURCE AND JURISDICTION Municipal Provincial Total -

List of Streets in Toronto East York That Can Be Converted to Permit Parking Page 1 of 53

List of streets in Toronto East York that can be converted to Permit Parking Page 1 of 53 Ward Street Between Length (m) 14 Budapest Lane Lake Shore Boulevard West and the south end of Budapest Lane 35.4 14 Cowan Avenue Milky Way and Queen Street West 49.0 T.T.C loop immediately south of Springhurst Avenue and 14 Dufferin Street Springhurst Avenue 84.8 Dundas Street West and Lane first west of Dundas Street West 14 Edna Avenue north of Edna Avenue 41.4 Lane first east of Dorval Road north of Edna Avenue and Dorval 14 Edna Avenue Road 45.3 Lane first west of Dundas Street West north of Edna Avenue and 14 Edna Avenue Lane first east of Dorval Road north of Edna Avenue 77.1 14 Elm Grove Avenue Milky Way and Queen Street West 49.7 14 Fraser Avenue Liberty Street and King Street West 215.7 14 Fraser Avenue The south end of Fraser Avenue and Liberty Street 276.0 14 Glenavon Road Dowling Avenue and the west end of Glenavon Road 93.7 14 Gwynne Avenue Milky Way and Queen Street West 50.0 Bloor Street West and Lane first north of Bloor Street West east 14 Indian Road of Indian Road 48.0 Lane first north of Bloor Street West east of Indian Road and 14 Indian Road Edna Avenue 50.8 Lane first south of King Street West east of Jefferson Avenue and 14 Jefferson Avenue King Street West 147.1 Lane first south of Liberty Street east of Jefferson Avenue and 14 Jefferson Avenue Liberty Street 65.9 Liberty Street and Lane first south of King Street West east of 14 Jefferson Avenue Jefferson Avenue 68.1 The south end of Jefferson Avenue and Lane first south -

Annual Report 2019

Newcomer Tour of Norfolk County Student Start Up Program participants Tourism & Economic Development Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Business Incentives & Supports ...................................................................................... 5 Investment Attraction ..................................................................................................... 11 Collaborative Projects ................................................................................................... 14 Marketing & Promotion .................................................................................................. 20 Strategy, Measurement & Success ............................................................................... 31 Performance Measurement ........................................................................................... 32 Advisory Boards ............................................................................................................ 33 Appendix ....................................................................................................................... 35 Staff Team ..................................................................................................................... 40 Prepared by: Norfolk County Tourism & Economic Development Department 185 Robinson Street, Suite 200 Simcoe ON N3Y 5L6 Phone: 519-426-9497 Email: [email protected] www.norfolkbusiness.ca -

2019 Election: Seat Clusters June to September Survey Results

2019 Election: Seat Clusters June to September Survey Results August 2019 2 Overview In Canada, we count seats, not vote. Just like in American Presidential elections, you can win the popular vote and lose the election. In fact, that happened to Justin Trudeau’s father in 1979. The general way analysts address that is to look at seats by region. However, seats in the same region can move differently. This release tries to get closer to reality in the seat-by-seat contest. Our analysis combines two projects: • An analysis of federal election districts (which we call “seats”) that groups them into 14 clusters based on which parties are most competitive in those seats. Given the shifting dynamics of Canada’s party system, we have relied on only the results of the past two elections. However, to assess where the parties stand in these 14 seat clusters, we need a lot of data. • A merge of the most recent three national surveys that include federal votes, creating a unweighted total of 7,555 respondents and a weighted total of 4,900. In each of our surveys, we collect postal codes. That allows us to create a riding variable for almost all our respondents and to group their responses by the riding they are in. The deck below shows the output from the analysis. The key finding is that, with the NDP in the doldrums, the Liberals are in a strong position coming into the race. Not only have they cemented their hold on last elections core seats, they may be able to gain seats to offsets the losses they will likely experience in the Toronto and Vancouver suburbs and Atlantic Canada. -

It Takes a Community to Raise a Child …

United Way 417 Bagot Street Kingston, ON K7K 3C1 (613) 542-2674 www.uway.kingston.on.ca Success By 6 It takes a community to raise a child … A position paper on priorities to help all children in Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox & Addington succeed for life. October 2005 Success by 6 is a United Way coordinated initiative ensuring all children succeed for life 2005, United Way serving KFL&A. All rights reserved. Consulting support provided by 8020info Inc. Success By 6 Position Paper -- 2005 Page 2 of 44 Success By 6 Priority Paper Contents Introduction .............................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary .............................................................................. 5 The Issues As We See Them: Early Learning and Early Childhood Development Opportunities ...... 10 Parenting Skills .................................................................................... 15 Housing and Homelessness Issues ....................................................... 18 Impacts of Poverty ............................................................................... 23 Success By 6 Initiatives ........................................................................ 24 Appendices: Program level Action - Parent Education ............................................ 29 Support for Those at Risk of Losing Housing ..................................... 30 Nine-Point Plan to Give Children a Great Start ................................... 32 Key Informants and Project Participants -

Old Town Toronto East

ST NTO EA TORO TOWN OLD Come and explore Toronto’s historic heart. N Sherbourne S Sac 5 kvi Geo ll Queen Street East e St rge Sum Bri Stre 4 ght Pow tre ach et Stre et er St Stre ree et St. t et Richmond Street East La Ber wre keley nce St Str 2 3 reet East ee Sac g Street t Adelaide Street East Kin kvi lle Str Jar Parli Bayv ee vis 6 t ament iew Cyp Street 1 ue Av St ven ress by Eri King Street East 7 enue Street Der n A n St ter St Eas ree E W t 14 Front Street East Don Ri Ove Tri 13 12 nity rend 11 ver St St reet The Esplanade 9 Mill Street Che 1O rry Geo 8 Street rge Scadding Ave Hah St South n Pl Longboat Avenue Lakeshore Blvd S Legend_ The Daniel Brooke Building 6 Little Trinity Church & Parish House 11 The Berkeley Street Theatre Bus, Streetcar Route Architectural/ 1 Historical 2 The Bank of Upper Canada 7 Enoch Turner School House 12 Canadian Opera Company Municipal Parking Interest 3 Toronto’s First Post Office 8 The Distillery Historic District 13 The Lorraine Kimsa Theatre Outdoor Art, Museum for Young People d Nixon 9 First Parliament Buildings Site One-way Street Statues & St. Paul’s Basilica 14 The Toronto Sun Mural Structures 4 10 Crombie Park Greenspace 5 Dominion Square riting: Edwar W EAST RONTO OWN TO OLD T Come and explore Toronto’s historic heart. Points of interest 1 The Daniel Brooke Building (King outskirts of town and the only Roman 9 First Parliament Buildings Site, Street East & Jarvis Street) Built in Catholic parish between Kingston and Parliament Square The block bounded 1833 for merchant Daniel Brooke, Windsor. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

Consultation Guide Final

Citizens Talking to Citizens Public Consultation Guide Ontario Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform Contact Information Print copies of this document are available at ServiceOntario/Government Information Centres in more than 60 communities around the province. For the location closest to you, please visit www.serviceontario.ca. Electronic copies are available in .pdf.Visit the Citizens’Assembly website at www.citizensassembly.gov.on.ca. Alternative-format copies are available on request at [email protected] Une publication équivalente est disponible en français au site web suivant : www.assembleedescitoyens.gouv.on.ca. © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2006 O ntario has changed significantly since Get Involved our first parliament was elected in 1792. Since that time the electoral system has The Assembly would like to hear from as never been publicly considered or evaluated. many Ontarians as possible: those who Some people think the current system know a lot about electoral systems, and has stood the test of time. Other people those who are just beginning to think or think it’s time for a change.The Citizens’ learn about the subject.The consultation Assembly process gives all Ontarians an period will run from late October 2006 to opportunity to learn more about Ontario’s the end of January 2007.What you tell us current electoral system, as well as others, will assist the Assembly when we discuss and to decide which one they think is what to recommend to the government. best for this province. This guide will help you present your The Citizens’ Assembly wants to ideas to the Assembly, however you hear what you think. -

Toronto North and East Office Market Report

First Quarter 2019 / Office Market Report Toronto North & East Quick Stats Leasing activity in the Toronto North its downward trend, dropping 30 bps 9.2% and East office markets started 2019 on during the quarter (the fourth consecutive North Yonge class A office a positive note, building on the overall quarter with a drop), but has risen 50 bps vacancy rate success of 2018. Collectively, occupancy year-over-year to 6.7%. The North market’s levels increased by 85,000 square feet (sf) most notable lease transactions during 34% with class C buildings marginally making up the quarter were in North Yonge, where Hwy. 404 & Steeles sublet the bulk of the gain. Quarter-over-quarter, Questrade consolidated operations from two available space as a percentage availability declined by 40 basis points (bps) buildings into one and extended its lease at of total available space to 11.3% while overall vacancy fell 40 bps Manulife’s North American Centre (105,000 to 7.1%. The amount of space on the sublet sf) and tech firm Alithya Technology leased a market increased by almost 250,000 sf full floor in RioCan’s 2 Sheppard Ave. E. 88,227 sf quarter-over-quarter, offering nearly 920,000 Sublet available area in Toronto After years in flux, Menkes Developments sf – mainly credited to new offerings in the North, vs. 829,143 sf in has reached a settlement with the City of Toronto East East market. Toronto for its development at 4800 Yonge Toronto North saw occupancy levels fall by St. (at the southwest corner of Yonge St. -

Lake Ontario South Shore 2012 Watershed Report Card

Lake Ontario South Shore 2012 Watershed Report Card Surface Water Quality and Natural Heritage LakeBlack OntarioCreek Lake Ontario Eighteen Mile Creek Forty Mile Creek Niagara River Frenchmans Creek Spring Creek Twenty Mile Creek North Creek Sixteen Mile Kraft Drain Creek Fifteen Mile Six Mile Creek Creek Groundwater Lake Ontario New York Lake Erie Lake Ontario Kilometers HamiltonHamilton 04.5913.518¯ NewNew YoYo rk rk General Natural Areas Successional w« Surface Water Quality Monitoring Station Rock Barren Wetland A! Provincial Groundwater Monitoring Network Bluff Swamp Watercourses Shoreline Wooded Area Significant Groundwater Recharge Area HaldimandHaldimand Open Water Provincially Significant Wetland Highly Vulnerable Aquifer Locally Significant Wetland Subwatershed Boundary Lake Erie Area of Natural and Scientific Interest Sampled Subwatershed LAKE ONTARIO SOUTH SHORE Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority 250 Thorold Rd., Welland, Ontario L3C 3W2 905-788-3135 [email protected] Watershed Characteristics Area 598 km2 encompassing Forty Mile Creek, Twenty Mile Creek, and 15-16-18 Mile Creek. Agriculture is the predominant land use and focuses on corn and wheat, hay, vineyards and orchards, greenhouses, and pasture. Concentrations of residential land uses occur in urban areas within Grimsby, Land Use Hamilton, North Pelham, Lincoln and West Lincoln. There are many natural areas in the watershed such as the Bruce Trail, The Waterfront Trail, and Ball’s Falls. Opportunities for fishing and boating, hiking, hunting, and golfing are available within the watershed. 1% Upland Escarpment, <0.1% Beach, 6% Developed Area, 48% Mixed Clay and Loam, 4% Mixed Sand and Soil Type Loam, 40% Mixed Silt and Loam, 0.1% Organic Soil, 1% Water, 0.4% Unknown Most of the watershed falls on the northern edge of the Haldimand Clay Plain.