Onto the National Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 5, 2017 No. 59 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was us, we must never forget those who de- about World War I and those who gave called to order by the Speaker pro tem- fended and protected freedom. so much during it. pore (Mr. WEBSTER of Florida). Many of us in Congress, as well as I hope my colleagues will join me in f citizens all over this country, are rel- cosponsoring H. Con. Res. 41. atives of World War I veterans. Many f DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO like myself had a grandparent who TEMPORE fought for this Nation. Many lost their RISE UP MAY 1 The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- relatives to this war, while many rel- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The fore the House the following commu- atives returned from war forever Chair recognizes the gentleman from nication from the Speaker: changed. Over 116,000 were killed, over Illinois (Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ) for 5 minutes. Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, if WASHINGTON, DC, 200,000 wounded, and over 70,000 suf- April 5, 2017. fered the effects of inhaling chlorine Donald Trump is going to be successful I hereby appoint the Honorable DANIEL gas dispelled by German military. as a President—successful from his WEBSTER to act as Speaker pro tempore on My grandfather was one of the 70,000, point of view; not the point of view of this day. -

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

A Bibliography

Reno Divorce History – A Bibliography compiled by Mella Harmon Books - General Nonfiction and Miscellaneous Books and Chapters - Pre-1970 A to Z Directory Publishers 1930 A to Z Directory and Guide Book, 1929-1930. Reno Printing Company, Reno. 1933 A to Z Directory and Guide Book, 1932-1933. Reno Printing Company, Reno. Anonymous 1953 Fun in Reno and the Far West! Publisher unknown. Barnett, James Harwood 1939 Divorce and the American Divorce Novel, 1858-1937. Reissued 1968. Russell and Russell, New York. Bartlett, George 1931 Men, Women and Conflict. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, London. 1947 Is Marriage Necessary? Revised edition. Penguin Books, Inc., New York. Beebe, Lucius 1968 Reno: Specialization and Fun. In Strauss, Anselm L., The American City: A Sourcebook of Urban Imagery. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, 431-433. Bender-Moss Company 1942 Nevada Compiled Laws, Supplement 1931-1941. Bender-Moss Company, San Francisco. Bixler, W.K. 1964 The Life and Times of Clel Georgetta, a Pictorial Biography. Sierra Publications. Bolin, James H. 1924 Reno, Nevada, the Holy City of the World. Distributed by Bolin Publishing Co., Reno. Bond, George W. 1921 Six Months in Reno. Stanley Gibbons, Inc., New York. Clark, Walter Van Tilburg 1949 Reno: The State City. In Rocky Mountain Cities, edited by Ray B. West, Jr. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York. Curtis, Leslie 1912 Reno Reveries. Chas. E. Weck, Distributing Agent, Reno. 1924 Reno Reveries. Armanko Stationery Co., Reno. David, W. M. 1928 Ramblings through the Pines and Sage: A Series of One Day Tours out of Reno. W. M. David for Nevada State Automobile Association. -

The Constituency of Coya Knutson, 1954

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 8-1982 The onsC tituency of Coya Knutson, 1954 Gretchen Urnes Beito Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Beito, Gretchen Urnes, "The onC stituency of Coya Knutson, 1954" (1982). Theses and Dissertations. 1158. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSTITUENCY OF COYA KNUTSON, 1954 by Gretchen Urnes Beito Bachelor of Science, University of Minnesota, 1957 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial ful. illment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota August 1982 Copyri~ht by Gretchen Urnes Beito 1982 il This Thesis submitted by Gretchen Urnes Beito in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North .. Dakota is here by approved by the.Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done. ------ ---··~M./\.1\.. ----'."··--·-~ Permission Title The Constituency of coya Knutson, 1954 Department _History Degree--- Master of Arts . In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the.requiternents for a graduate degree from the University of North D~kota, I agr~e that the Library of this Univer sity shall make it freely available for inspection. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

69- 13,912 BEDDOW, James Bellamy, 1942- ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1969 History, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JAMES BELLAMY BEDDOW Norman, Oklahoma 1969 ECONOMIC NATIONALISM OR INTERNATIONALISM: UPPER MIDWESTERN RESPONSE TO NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY, 1934-1940 APfPUVED BY L y —, DISSERTATION COMMITI^E TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE................................................... iv Chapter I. MIDWESTERN AGRICULTURE AND THE TARIFE . I II. RECIPROCAL TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM ENACTED ............................. 13 III. ORGANIZATIONAL RESPONSE TO THE RECIPROCAL TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM . 4] IV. NEW DEAL TARIFF POLICY AND THE ELECTION OF I936............................. 6? V. TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM RENEWED...............96 VI. AMERICAN NATIONAL LIVE STOCK ASSOCIATION OPPOSES THE TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM.......................... 128 VII. MIDWESTERN REACTION TO TRADE AGREEMENTS WITH GREAT BRITAIN AND CANADA .............144 VIII. THE NEW DEAL PROPOSES A TRADE AGREEMENT WITH ARGENTINA................... .....182 IX. TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM RENEWED............. 200 X. CONCLUSIONS ....................................244 -

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

2015 Annual Report

Maryland Commission for Women Annual Report n July 2014 – June 2015 ii Table of Contents Message from the Secretary .........................................................................3 Message from the Chair ...............................................................................4 Report of the Executive Director .................................................................5 Setting the Agenda .......................................................................................7 Building Partnerships ...................................................................................9 Advocating for Maryland’s Women ...........................................................12 Recognizing Women of Historic Significance ........................................... 14 Encouraging Leadership in Young Women ............................................... 16 Improving Access to Health Resources ..................................................... 19 Reaching Out ............................................................................................. 21 Strengthening Our Work Structure ............................................................22 Supporting Women in Transition ...............................................................23 In Memoriam .............................................................................................24 Maryland Commission for Women Annual Report n July 2014 – June 2015 Maryland Commission for Women July 2014 – June 2015 Officers: Dr. Kathleen White, Chair Mythili (Lee) Bachu, -

BOB DOLE Unf Ej States Senate BD: Bj

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. http://dolearchives.ku.edu ecember 3, 1970 rs. Christine Stevens, Secretary Society for Animal Protection Legislation P. 0. Box 3719 Washington, D. C. 20007 Dear rs. Stevens: C rtainly thank you for sending me a copy of your Newsletter regarding the Animal Welfare Act of 1970. Very ch appreciate your co ents, and hopefully, we will be successful in expediting passage of this important legislation. In the meanti , if there is any way I may b of assistance, let me know. Sincerely yours, BOB DOLE Unf eJ States Senate BD: bj Page 1 of 6 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. http://dolearchives.ku.edu · Witittb ~tatts ~tnatt MEMORANDUM Senator Dole---- FYI Mrs. Stevens called last week and I sent your statement. Hyde says she is one of the prime boosters of this bill. She is also the wife of Roger Stevens, who Gyde says runs the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. tag Page 2 of 6 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. SOCIETY FOR ANIMAL PROTECTIVE LEGISLATION http://dolearchives.ku.edu P. 0. Box 3719 Georgetown Station Washington, D. C. 20007 November 30, 1970 Mr. William Taggart Office of Senator Robert Dole Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. Taggart, Thanks for sending me the Senator's remarks when he introduced the Animal Welfare Act of 1970. I appreciate your getting this off to me in New York. This made it possible to quote Senator Dole in the enclosed circular letter which we have sent out to interested persons throughout the country. -

The United States Government Manual 2002/2003

The United States Government Manual 2002/2003 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration VerDate 11-MAY-2000 02:14 Aug 24, 2002 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 W:\DISC\189864PL.XXX txed01 PsN: txed01 Revised June 1, 2002 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States. On the cover: Photograph by Ansel Adams of an unnamed peak in Kings River Canyon, California, circa 1936. From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration. Ansel Adams (1902-1984) was one of America’s greatest landscape photographers. He is best known for his vistas of the American west and its national parks. His black-and-white photos capture the beauty and vastness of this Nation’s wilderness, as well as its stark simplicity. This year marks the 100th anniversary of his birth. For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–9328 ii VerDate 11-MAY-2000 02:14 Aug 24, 2002 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 W:\DISC\189864PL.XXX txed01 PsN: txed01 Preface As the official handbook of the Federal Government, The United States Government Manual provides comprehensive information on the agencies of the legislative, judicial, and executive branches. The Manual also includes information on quasi- official agencies; international organizations in which the United States participates; and boards, commissions, and committees. A typical agency description includes a list of principal officials, a summary statement of the agency’s purpose and role in the Federal Government, a brief history of the agency, including its legislative or executive authority, a description of its programs and activities, and a ‘‘Sources of Information’’ section. -

**ARCH 2006, Issue 2

I N S I D E : Historical Records Board established Flag added to collection Friends board holds spring meeting AY AT FRIENDS OF THE ALABAMA ARCHIVES Newsletter A D Published quarterly in support of the Alabama Department of Archives and History 2006, Issue 2 THE ARCHIVES MONDAY, APRIL 10, was a busy day at the Archives. At noon, friends of Gwyn Turner gathered in the Hale Room for a surprise ceremony (see story below). Later in the afternoon, the Alabama Archives and History Foundation held its fifth annual meeting. Seth Hammett, Speaker of the Alabama House, delivered the keynote address. He complimented the Foundation on its success at raising substantial funds to supplement the Archives’ state budget. He was pleased to note that the Legislature was able to follow Governor Riley’s recommendation for a significant budget increase for the Archives for the next fiscal year. “When we preserve history, we preserve our culture, and that unites us as a family,” Hammett said. The Foundation meeting ended with Ocllo Malone passing the presidential gavel to Charles Stakely. Mrs. Malone provided positive leadership during a year at the helm and helped move the Foundation significantly closer to its fundraising goals. She will continue to serve on the Executive Committee. Mr. Stakely, who takes over as President after a year as Vice President, is a Montgomery native and respected attorney and community leader. The board elected Temple Tutwiler as Vice President and Henry Lynn as Treasurer. In addition, the Foundation added one new member, Scott Vowell of Birmingham. The day culminated with a reception sponsored by Alabama Power Company, the opening of a temporary exhibit on its 100-year history, and the dedication of the Alabama Power Auditorium in honor of the company’s seventh president, Joe Farley. -

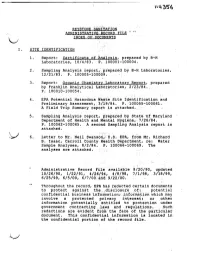

Administrative Record File Index of Documents

KEYSTONE SANITATION ADMINISTRATIVE^RECORD FILE INDEX OF DOCUMENTS I. SITE IDENTIFICATION /" - 1. Report: Certificate of Analysis, prepared by B-H Laboratories, 10/4/83. P. 100001-100004. 2. Sampling Analysis report,, prepared by B-H Laboratories, 12/21/83. P. 100005-100009. :;: 3. Report: Organic Chemistry Laboratory Report, prepared by Franklin Analytical Laboratories, 2/23/84. P. 100010-100054. 4. EPA Potential Hazardous Waste Site Identification.and Preliminary Assessment, 3/19/84. P. 100055-100061. A Field Trip Summary report is attached., ; 5. Sampling Analysis report, prepared by State rof Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 7/26/84. P. 100062-100065. A second Sampling Analysis report is attached. 6. Letter.to Mr. Neil Swanson^' U.S. EPA, from Mr, Richard B. Isaac, Carroll County Health Department, re: Water Sample Analyses, 8/2/84. P. 100066-100069. The analyses are attached. :: Administrative Record File available 8/20/90, updated 10/26/90, 1/22/91, 4/2.6/94, 4/8/98, 7/1/98, 3/18/99, 6/25/99, 6/5/00, 6/7/00:arid 9/22/00. Throughout the record, EPA has redacted certain documents to protect against the .disclosure . of: potential confidential business information; information which.may involve a protected privacy interest; or other information potentially entitled to protection under government contracting .laws and regulations. _Such redactions are evident from the face of the particular document. This confidential information is located in the confidential portion of the record file. 7. Sampling Analysis report, prepared by State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 9/13/84.