Concepts and Practices Centralization and Decentralization in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

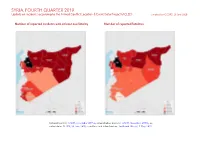

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 1 - 8 September 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 1 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government of Syria (GoS) momentum slowed in Idleb this week, with no advances recorded. Further civilian protests denouncing Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS) took place in the northwest, in addition to pro-HTS and pro-Hurras al Din demonstrations. HTS and Jaish al Izza also launched a recruitment drive in the northwest. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Attacks against GoS-aligned personnel and former opposition members continued in southern Syria, including two unusual attacks claimed by ISIS. GoS forces evicted civilians and appropriated several hundred houses in Eastern Ghouta. • NORTHEAST | The first joint US/Turkish ground patrol took place in Tal Abiad this week as part of an ongoing implementation of the “safe zone” in northern Syria. Low-level attacks against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and SDF arrest operations of alleged ISIS members continued. Two airstrikes targeting Hezbollah and Iranian troops occurred in Abu Kamal. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 8 September 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 1 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 GoS momentum in southern Idleb Governorate slowed this week, with no advances recorded. This comes a week after Damascus announced a ceasefire for the northwest on 31 August that saw a significant reduction in aerial activity, with no events recorded in September so far. However, GoS shelling continued impacting the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated enclave, with at least 26 communities2 affected (Figure 2). -

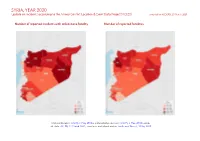

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Summry Report of Maarat Al-Numan

Cover Image: VDC SY Introduction Many villages and regions in Idlib governorate were subjected to hundreds of unlawful airstrikes that resulted in many horrific massacres against civilians. According to figures from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, these massacres left dozens of dead and hundreds of wounded and were a direct cause of the displacement of at least 235.000 people, including at least 140.000 children, from southern Idlib Since 12 December. Moreover, these airstrikes have affected thousands of homes, most of which have been almost completely destroyed. The airstrikes launched by the Syrian Air Force and Russian war fighters were intensified especially in the middle of December 2019 and during the days that followed, dozens of densely populated residential neighborhoods were targeted, systematic and regular attacks were recorded that clearly and unambiguously targeted civil- ian neighborhoods, killing hundreds of civilians and causing huge losses of property to the residents, especially in terms of destroying homes, shops and commercial facilities. 2 Summary The Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC) warns of the catastrophic consequences of the military escalation of Syrian government forces and Russian forces in the Maarat al-Numan area, foremost among them is the pushing of thousands of civilians to forced displacement from the region, as the attacks by the Syrian government and Russian forces are using warplanes, heli- copters and surface-to-surface missiles targeting civilian objects, markets, infrastructure, as well as advances on the ground are forcing civilians to be forced displaced from their homes, which will deepen the humanitarian crisis in Idlib governorate. -

132484385.Pdf

MAANPUOLUSTUSKORKEAKOULU VENÄJÄN OPERAATIO SYYRIASSA – TARKASTELU VENÄJÄN ILMAVOIMIEN KYVYSTÄ TUKEA MAAOPERAATIOTA Diplomityö Kapteeni Valtteri Riehunkangas Yleisesikuntaupseerikurssi 58 Maasotalinja Heinäkuu 2017 MAANPUOLUSTUSKORKEAKOULU Kurssi Linja Yleisesikuntaupseerikurssi 58 Maasotalinja Tekijä Kapteeni Valtteri Riehunkangas Tutkielman nimi VENÄJÄN OPERAATIO SYYRIASSA – TARKASTELU VENÄJÄN ILMAVOI- MIEN KYVYSTÄ TUKEA MAAOPERAATIOTA Oppiaine johon työ liittyy Säilytyspaikka Operaatiotaito ja taktiikka MPKK:n kurssikirjasto Aika Heinäkuu 2017 Tekstisivuja 137 Liitesivuja 132 TIIVISTELMÄ Venäjä suoritti lokakuussa 2015 sotilaallisen intervention Syyriaan. Venäjä tukee Presi- dentti Bašar al-Assadin hallintoa taistelussa kapinallisia ja Isisiä vastaan. Vuoden 2008 Georgian sodan jälkeen Venäjän asevoimissa aloitettiin reformi sen suorituskyvyn paran- tamiseksi. Syyrian intervention aikaan useat näistä uusista suorituskyvyistä ovat käytössä. Tutkimuksen tavoitteena oli selvittää Venäjän ilmavoimien kyky tukea maaoperaatiota. Tutkimus toteutettiin tapaustutkimuksena. Tapauksina työssä olivat kolme Syyrian halli- tuksen toteuttamaa operaatiota, joita Venäjä suorituskyvyillään tuki. Venäjän interventiosta ei ollut saatavilla opinnäytetöitä tai kirjallisuutta. Tästä johtuen tutkimuksessa käytettiin lähdemateriaalina sosiaaliseen mediaan tuotettua aineistoa sekä uutisartikkeleita. Koska sosiaalisen median käyttäjien luotettavuutta oli vaikea arvioida, tutkimuksessa käytettiin videoiden ja kuvien geopaikannusta (geolocation, geolokaatio), joka -

The 12Th Annual Report on Human Rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013)

The 12th annual report On human rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013) January 2014 January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Arbitrary detention and Enforced Disappearances 11 Besiegement: slow-motion genocide 14 Violations committed against health and the health sector 17 The conditions of Syrian refugees 23 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 27 Violations committed against freedom of the press 31 Violations committed against houses of worship 39 The targeting of historical and archaeological sites 44 Legal and legislative amendments 46 References 47 About SHRC 48 The 12th annual report on human rights in Syria (January 2013 – December 2013) Introduction The year 2013 witnessed a continuation of grave and unprecedented violations committed against the Syrian people amidst a similarly shocking and unprecedented silence in the international community since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. Throughout the year, massacres were committed on almost a daily basis killing more than 40.000 people and injuring 100.000 others at least. In its attacks, the regime used heavy weapons, small arms, cold weapons and even internationally prohibited weapons. The chemical attack on eastern Ghouta is considered a landmark in the violations committed by the regime against civilians; it is also considered a milestone in the international community’s response to human rights violations Throughout the year, massacres in Syria, despite it not being the first attack in which were committed on almost a daily internationally prohibited weapons have been used by the basis killing more than 40.000 regime. The international community’s response to the crime people and injuring 100.000 drew the international public’s attention to the atrocities others at least. -

Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’S Four Towns Agreement Through Elicitive Conflict Mapping

MASTERS OF PEACE 19 Lama Ismail Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’s Four Towns Agreement through Elicitive Conflict Mapping innsbruck university press MASTERS OF PEACE 19 innsbruck university press Lama Ismail Re-Imagining Peace: Analyzing Syria’s Four Towns Agreement through Elicitive Conflict Mapping Lama Ismail Unit for Peace and Conflict Studies, Universität Innsbruck Current volume editor: Josefina Echavarría Alvarez, Ph.D This publication has been made possible thanks to the financial support of the Tyrolean Education Institute Grillhof and the Vice-Rectorate for Research at the University of Innsbruck. © innsbruck university press, 2020 Universität Innsbruck 1st edition www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-903187-88-7 For Noura Foreword by Noura Ghazi1 I am writing this foreword on behalf of Lama and her book, in my capacity as a human rights lawyer of more than 16 years, specializing in cases of enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention. And also, as an activist in the Syrian uprisings. In my opinion, the uprisings in Syria started after decades of attempts – since the time of Asaad the father, leading up to the current conflict. Uprisings have taken up different forms, starting from the national democratic movement of 1979, to what is referred to as the Kurdish uprising of 2004, the ‘Damascus Spring,’ and the Damascus- Beirut declaration. These culminated in the civil uprisings which began in March 2011. The uprisings that began with the townspeople of Daraa paralleled the uprisings of the Arab Spring. Initially, those in Syria demanded for the release of political prisoners and for the uplift of the state of emergency, with the hope that this would transition Syria’s security state towards a state of law. -

SYRIA - IDLEB Humanitarian Purposes Only IDP Location - As of 23 Oct 2015 Production Date : 26 Oct 2015

SYRIA - IDLEB Humanitarian Purposes Only IDP Location - As of 23 Oct 2015 Production date : 26 Oct 2015 Nabul Al Bab MARE' JANDAIRIS AFRIN NABUL Tadaf AL BAB Atma ! Qah ² ! Daret Haritan Azza TADAF Reyhanli DARET AZZA HARITAN DANA Deir Hassan RASM HARAM !- Darhashan Harim Jebel EL-IMAM Tlul Dana ! QOURQEENA Saman Antakya Ein Kafr Hum Elbikara Big Hir ! ! Kafr Mu Jamus ! Ta l ! HARIM Elkaramej Sahara JEBEL SAMAN Besnaya - Sarmada ! ! Bseineh Kafr ! Eastern SALQIN ! Qalb Ariba Deryan Kafr ! Htan ! Lozeh ! Kafr Naha Kwaires ! Barisha Maaret ! ! Karmin TURKEY Allani ! Atarib ! Kafr Rabeeta ! Radwa ! Eskat ! ! Kila ! Qourqeena Kafr Naseh Atareb Elatareb Salqin Kafr ! EASTERN KWAIRES Delbiya Meraf ! Kafr Elshalaf Takharim Mars ! Kafr ! Jeineh Aruq ! Ta lt i t a ! Hamziyeh ! Kelly ! Abu ! Ta lh a ATAREB ! Kaftin Qarras KAFR TAKHARIMHelleh ! Abin ! Kafr ! Hazano ! Samaan Hind ! Kafr ! Kuku - Thoran Ein Eljaj ! As Safira Armanaz ! Haranbush ! Maaret Saidiyeh Kafr Zarbah ! Elekhwan Kafr - Kafr ! Aleppo Kafrehmul ! Azmarin Nabi ! Qanater Te ll e m ar ! ! ! ! Dweila Zardana AS-SAFIRA ! Mashehad Maaret Elnaasan ! Biret MAARET TAMSRIN - Maaret Ramadiyeh Elhaski Ghazala -! Armanaz ! ! Mgheidleh Maaret ! ARMANAZKuwaro - Shallakh Hafasraja ! Um Elriyah ! ! Tamsrin TEFTNAZ ! Zanbaqi ! Batenta ! ALEPPO Milis ! Kafraya Zahraa - Maar Dorriyeh Kherbet ! Ta m sa ri n Teftnaz Hadher Amud ! ! Darkosh Kabta Quneitra Kafr Jamiliya ! ! ! Jales Andnaniyeh Baliya Sheikh ! BENNSH Banan ! HADHER - Farjein Amud Thahr Yousef ! ! ! ! Ta lh i ye h ZARBAH Nasra DARKOSH Arshani -

EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB on the VERGE of IMPLOSION Dr

EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 August 2019 EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB ON THE VERGE OF IMPLOSION Dr. Can Kasapoglu | Director of Security and Defense Research Program Emre Kursat Kaya | Researcher EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB ON THE VERGE OF IMPLOSION Dr. Can Kasapoglu | Director of Security and Defense Research Program Emre Kursat Kaya | Researcher Greater Idlib Region and the Turkish (Blue), Russian (Red) and Iranian (Orange) observation posts - Modified map, original from Liveuamap.com What Happened? On August 19th, 2019, the Syrian Arab Air Force launched an have intensified around Maarat al-Nu’man, another M5 airstrike, halting the Turkish military convoy that was heading choke point. In the meanwhile, the Syrian Araby Army’s to the 9th observation post in Morek. (The observation posts maneuvers have effectively isolated the Turkish observation around Idlib were established as an extension of the Astana post. Furthermore, the Turkish convoy, which had been en process brokered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran). The attack route to Morek in the beginning, has set defensive positions took place along the M5 highway, north of Khan Sheikhun, in a critical location between Khan Sheikun and Maarat a critical choke-point. Subsequently, Assad’s forces have al-Nu’man. The Syrian Arab Army, supported by Russian boosted their offensive and captured the geostrategically airpower, is preparing for a robust assault in greater Idlib critical town. At present, the regime’s military activities that could exacerbate troublesome humanitarian problems. 2 EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 Significance: The regime offensive could displace millions of people Turkish forward-deployed contingents and the Syrian in Idlib and overwhelm Turkey’s security capacity to keep Arab Army’s elite units are now positioned dangerously Europe safe. -

Regional Analysis Syria

Overview REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Total number ‘in need of assistance’: 4 million Number of governorates affected by conflict: 14 out of 14 28 January 2013 Content Part I Overview Part I – Syria Information gaps and data limitations Operational constraints This Regional Analysis of the Syria Conflict (RAS) seeks to bring together information from all sources in Humanitarian profile the region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Country sectoral analysis Syria crisis. While Part I focuses on the situation Governorate profiles within Syria, Part II covers the impact of the crisis on Forthcoming reports the neighbouring countries. The Syria Needs Analysis Annex A: Baseline Data Project welcomes all information that could complement this report. For additional information, Annex B: Definitions Humanitarian Profile comments or questions, please email Annex C: Stakeholder profile [email protected] Priority needs The priority needs below are based on known information. Little or no information is Multiple media sources available for Al-Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Lattakia and Tartous in the north and for As-Sweida, Damascus city, Damascus rural and Quneitra in the south. This is due to the prioritisation of other governorates, limited information sharing and to access issues. Information is being gathered on some cities and governorates (such as Aleppo, Idleb, Dar’a and Homs) although not all is available to the wider humanitarian community for a variety of reasons. Displacement: There is little clear information on the number of IDPs: ministries PROTECTION is a priority throughout the country, specifically: of the GoS report 150,000 IDPs residing in 626 collective centres and more in some 1,468 schools but no figures are available for the number residing in direct threat to life from the conflict private accommodation (with or without host families).