Bulletin 114B.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAREN Gaulke Muhliusstrasse 84, 24103 Kiel 1, Germany

Asiatic Research Vol. 6, I June 1995 Herpetolo^ical pp. WW Observations on Arboreality in a Philippine Blind Snake MAREN Gaulke Muhliusstrasse 84, 24103 Kiel 1, Germany Abstract. -Five blind snakes were observed in June 1990 in the rain forests of Sibutu Island in the Sulu Archipelago, Philippines. Contrary to the usually fossorial habits of typhlopids, Ramphotyphlops suluensis (Taylor, 1918) shows arboreal habits. It climbed through trees at night using the prehensile tail and hindbody. When caught they extruded a strong smelling liquid from their cloaca. Relatively long tails are found in some other rain forest dwelling typhlopids, which may also have arboreal habits. Key words: Reptilia, Ophidia, Typhlopidae, Ramphotyphlops suluensis, Philippines, ecology. and the relative humidity between 70 and Introduction 95%. Little is known of the behavior of blind The nomenclatural history and taxonomy snakes (Typhlopidae). Information is of the typhlopids observed and caught on normally generalized and consists of little Sibutu is discussed in Gaulke (in press), more than that typhlopids are small, where the species, previously synonymized burrowing snakes, which live in decaying with Ramphotyphlops olivaceus (Gray, logs, humus and leaf litter, and feed mainly 1845), is revalidated. Ramphotyphlops on ants and termites, especially their grubs, suluensis reaches a length of approximately pupae and eggs (e. g. Taylor, 1922; 40 cm, the eyes are distinctive, and the tail is Loveridge, 1946; Gruber, 1980). more than twice as long as broad. The dorsal side is gray, the ventral side is cream, This gap in observations is certainly due with bright white scales along the median to a number of different factors. -

A New Record of the Christmas Island Blind Snake, Ramphotyphlops Exocoeti (Reptilia: Squamata: Typhlopidae)

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 27 156–160 (2012) A new record of the Christmas Island Blind Snake, Ramphotyphlops exocoeti (Reptilia: Squamata: Typhlopidae). Dion J. Maple1, Rachel Barr, Michael J. Smith 1 Christmas Island National Park, Christmas Island, Western Australia, Indian Ocean, 6798, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The endemic Christmas Island Blind Snake Ramphotyphlops exocoeti is a species rarely collected since initial faunal collections were conducted on Christmas Island in 1887. Twenty-three years after the last record in 1986, an individual was collected on 31 July 2009. Here we catalogue historical collection records of this animal. We also describe the habitat and conditions in which the recent collection occurred and provide a brief morphological description of the animal including a diagnostic feature that may assist in future identifi cations. This account provides the fi rst accurate spatial record and detailed description of habitat utilised by this species. KEYWORDS: Indian Ocean, Yellow Crazy Ant, recovery plan INTRODUCTION ‘fairly common’ and could be found under the trunks Christmas Island is located in the Indian Ocean of fallen trees. In 1975 a specimen collected from (10°25'S, 105°40'E), approximately 360 km south of the Stewart Hill, located in the central west of the island western head of Java, Indonesia (Geoscience Australia in a mine lease known as Field 22, was deposited in 2011). This geographically remote, rugged and thickly the Australian Museum (Cogger and Sadlier 1981). A vegetated island is the exposed summit of a large specimen was caught by N. Dunlop in 1984 while pit mountain. -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

A Taxonomic Framework for Typhlopid Snakes from the Caribbean and Other Regions (Reptilia, Squamata)

caribbean herpetology article A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata) S. Blair Hedges1,*, Angela B. Marion1, Kelly M. Lipp1,2, Julie Marin3,4, and Nicolas Vidal3 1Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA. 2Current address: School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7450, USA. 3Département Systématique et Evolution, UMR 7138, C.P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. 4Current address: Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Article registration: http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47191405-862B-4FB6-8A28-29AB7E25FBDD Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 17 January 2014. Citation: Hedges SB, Marion AB, Lipp KM, Marin J, Vidal N. 2014. A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata). Caribbean Herpetology 49:1–61. Abstract The evolutionary history and taxonomy of worm-like snakes (scolecophidians) continues to be refined as new molec- ular data are gathered and analyzed. Here we present additional evidence on the phylogeny of these snakes, from morphological data and 489 new DNA sequences, and propose a new taxonomic framework for the family Typhlopi- dae. Of 257 named species of typhlopid snakes, 92 are now placed in molecular phylogenies along with 60 addition- al species yet to be described. Afrotyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed almost exclusively in sub-Saharan Africa and contains three genera: Afrotyphlops, Letheobia, and Rhinotyphlops. Asiatyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed in Asia, Australasia, and islands of the western and southern Pacific, and includes ten genera:Acutotyphlops, Anilios, Asiatyphlops gen. -

Northern Territory NT Page 1 of 204 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region Northern Territory, Northern Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

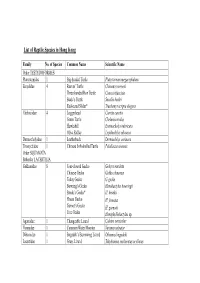

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong Family No. of Species Common Name Scientific Name Order TESTUDOFORMES Platysternidae 1 Big-headed Turtle Platysternum megacephalum Emydidae 4 Reeves’ Turtle Chinemys reevesii Three-banded Box Turtle Cuora trifasciata Beale’s Turtle Sacalia bealei Red-eared Slider* Trachemys scripta elegans Cheloniidae 4 Loggerhead Caretta caretta Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata Olive Ridley Lepidochelys olivacea Dermochelyidae 1 Leatherback Dermochelys coriacea Trionychidae 1 Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle Pelodiscus sinensis Order SQUAMATA Suborder LACERTILIA Gekkonidae 8 Four-clawed Gecko Gehyra mutilata Chinese Gecko Gekko chinensis Tokay Gecko G. gecko Bowring’s Gecko Hemidactylus bowringii Brook’s Gecko* H. brookii House Gecko H. frenatus Garnot’s Gecko H. garnotii Tree Gecko Hemiphyllodactylus sp. Agamidae 1 Changeable Lizard Calotes versicolor Varanidae 1 Common Water Monitor Varanus salvator Dibamidae 1 Bogadek’s Burrowing Lizard Dibamus bogadeki Lacertidae 1 Grass Lizard Takydromus sexlineatus ocellatus Scincidae 11 Chinese Forest Skink Ateuchosaurus chinensis Chinese Skink Eumeces chinensis chinensis Five-striped Blue-tailed Skink E. elegans Blue-tailed Skink E. quadrilineatus Vietnamese Five-lined Skink E. tamdaoensis Long-tailed Skink Mabuya longicaudata Slender Forest Skink Scincella modesta Reeve’s Smooth Skink S. reevesii Indian Forest Skink Sphenomorphus indicus Brown Forest Skink S. incognitus Chinese Waterside Skink Tropidophorus sinicus Order SQUAMATA Suborder SERPENTES Typhlopidae 3 Lazell’s Blind Snake Typhlops lazelli White-headed Blind Snake Ramphotyphlops albiceps Common Blind Snake R. braminus Boidae 1 Burmese Python Python molurus bivittatus Colubridae 34 Rufous Burrowing Snake Achalinus rufescens Jade Vine Snake Ahaetulla prasina medioxima Mountain Keelback Amphiesma atemporale White-browed Keelback A. boulengeri Buff-striped Keelback A. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Snakes of the Wet Tropics

Snakes of the Wet Tropics Snakes are protected by law Snakes are shy creatures. When confronted by humans, they will usually retreat if given the opportunity to do so. As most bites occur when people try to catch and kill snakes, they should always be left well alone. Snakes in the Wet Tropics The Wet Tropics region is home to 43 species of snakes, representing an impressive 30% of Australia’s snake fauna. These images represent a selection of the more common species, most of which have ranges extending beyond the Wet Tropics. Of the species pictured, only the northern crowned snake is unique to this region. The snakes of the region range from small, worm-like blind snakes to six metre pythons. Only a handful fall into the dangerously venomous category, but these few play an important role in balancing the natural environment, as they are significant predators of rats and mice. Snakes in the backyard If you live near bushland or creeks you are more likely to encounter snakes in your garden, especially if there is habitat disturbance such as burning or clearing of vegetation in the local area. To discourage snakes from taking up residence around your home remove likely hiding places such as logs, building materials, long grass, loose rocks, discarded flower pots and corrugated iron. Snakes in the house Snakes will sometimes enter a house in search of food and shelter - particularly during periods of extended rain. The risk of this happening can be reduced by having well-sealed doors and screens over external windows. -

Waite's Blind Snakes (Squamata: Scolecophidia

© Copyright Australian Museum, 1999 Records of the Australian Museum (1999) Vol. 51: 43–56. ISSN 0067–1975 Waite’s Blind Snakes (Squamata: Scolecophidia: Typhlopidae): Identification of Sources and Correction of Errors GLENN M. SHEA Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Pathology, University of Sydney NSW 2006, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT. The majority of the 542 typhlopid specimens examined by Edgar Waite for his 1918 monograph of the family are identified, and their current status discussed. Most Waite records that do not correspond with the distribution based on modern records are shown to be in error, involving either misidentifications, misreadings of localities, or transposition of data. A few remaining problematic records are considered dubious due to a lack of supporting data. Ramphotyphlops batillus (Waite, 1894), known only from the holotype from Wagga Wagga, NSW, is restored to the Australian fauna, and new data on the type are provided. Probable paratypes for Typhlops grypus (SAM R849; QM J2947), T. proximus (AM R615, R145401– 07, SAM R915) and T. subocularis (AM R2169) are identified. New data on dorsal scale counts are provided for Ramphotyphlops leucoproctus (377–394), R. polygrammicus (370–422), R. proximus (326– 392), R. wiedii (381–439) and R. yirrikalae (447–450). SHEA, GLENN M., 1999. Waite’s blind snakes (Squamata: Scolecophidia: Typhlopidae): identification of sources and correction of errors. Records of the Australian Museum 51(1): 43–56. Although a number of species of Australian typhlopid work, particularly his key, distribution maps and figures, snakes had been described by European herpetologists in has been the main source of much of the subsequent the nineteenth century, notably Wilhelm Peters and George literature on Australian typhlopids. -

Epictia-1.Pdf

The Leptotyphlopidae, descriptively called threadsnakes or wormsnakes, is one of five families comprising the most ancient but highly specialized clade of snakes, the Scolecophidia, which dates back to the Jurassic Period (ca. 155 mya). Scolecophidians are the least studied and poorest known group of snakes, both biologically and taxonomically. Due to their subterranean habitat, nocturnal lifestyle, small size, and drab coloration, these snake are extremely difficult to find and seldom are observed or collected. Epictia is one of six genera found in the New World, with a distribution extending throughout Latin America. Whereas most Epictia are uniform brown or black, some species are brightly colored. Epictia tenella, the most wide-ranging member of the genus, occurs throughout much of northern South America. Pictured here is an individual from Trinidad that exhibits several distinctive features, including yellow zigzag stripes, relatively large bulging eyes, contact of the supraocular and anterior supralabial shields, and the presence of numerous sensory pits on the anterior head shields. ' © John C. Murphy 215 www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com ISSN 2373-0951 Version of record:urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A6B8D5BF-2E06-485A-BD7F-712D8D57CDE4 Morphological review and taxonomic status of the Epictia phenops species group of Mesoamerica, with description of six new species and discussion of South American Epictia albifrons, E. goudotii, and E. tenella (Serpentes: Leptotyphlopidae: Epictinae) VAN WALLACH 4 Potter Park, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, United States. E–mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: I examined the “Epictia phenops species group” of Mesoamerica, and recognize 11 species as valid (E. ater, E. bakewelli, E. columbi, E. -

Reptiles on the Brink: Identifying the Australian Terrestrial Snake and Lizard Species Most at Risk of Extinction

CSIRO PUBLISHING Pacific Conservation Biology, 2021, 27, 3–12 https://doi.org/10.1071/PC20033 Reptiles on the brink: identifying the Australian terrestrial snake and lizard species most at risk of extinction Hayley M. Geyle A, Reid Tingley B, Andrew P. AmeyC, Hal CoggerD, Patrick J. CouperC, Mark CowanE, Michael D. CraigF,G, Paul DoughtyH, Don A. DriscollI, Ryan J. EllisH,J, Jon-Paul EmeryF, Aaron FennerK, Michael G. GardnerK,L, Stephen T. Garnett A, Graeme R. GillespieM, Matthew J. GreenleesN, Conrad J. HoskinO, J. Scott KeoghP, Ray LloydQ, Jane Melville R, Peter J. McDonaldS, Damian R. MichaelT, Nicola J. Mitchell F, Chris SandersonU,V, Glenn M. Shea W,X, Joanna Sumner R, Erik WapstraY, John C. Z. Woinarski A and David G. Chapple B,Z AThreatened Species Recovery Hub, National Environmental Science Program, Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909, Australia. BSchool of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Vic. 3800, Australia. CBiodiversity Program, Queensland Museum, South Brisbane, Qld 4101, Australia. DAustralian Museum, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia. EDepartment of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Kensington, WA 6151, Australia. FSchool of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia. GSchool of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA 6150, Australia. HDepartment of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Welshpool, WA 6106, Australia. ICentre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood, Vic. 3125, Australia. JBiologic Environmental Survey, East Perth, WA 6004, Australia. KCollege of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA 5042, Australia. LEvolutionary Biology Unit, South Australian Museum, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia.