Charles Schulz, US, Cartoonist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Incongruous Surrealism Within Narrative Animated Film

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2021 Incongruous Surrealism within Narrative Animated Film Daniel McCabe University of Central Florida Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation McCabe, Daniel, "Incongruous Surrealism within Narrative Animated Film" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 529. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/529 INCONGRUOUS SURREALISM WITHIN NARRATIVE ANIMATED FILM by DANIEL MCCABE B.A. University of Central Florida, 2018 B.S.B.A. University of Central Florida, 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts in the School of Visual Arts and Design in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2021 © Daniel Francis McCabe 2021 ii ABSTRACT A pop music video is a form of media containing incongruous surrealistic imagery with a narrative structure supplied by song lyrics. The lyrics’ presence allows filmmakers to digress from sequential imagery through introduction of nonlinear visual elements. I will analyze these surrealist film elements through several post-modern philosophies to better understand how this animated audio-visual synthesis resides in the larger world of art theory and its relationship to the popular music video. -

The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation with Charles Solomon and Lee Mendelson at the Charles M

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – October 29, 2012 Gina Huntsinger, Marketing Director Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center (707) 579-4452 #268 [email protected] Discussing The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation with Charles Solomon and Lee Mendelson at the Charles M. Schulz Museum Saturday, December 1, at 1:00 pm The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation by Charles Solomon will be released November 7 by Chronicle Books. (Santa Rosa, CA) Join Lee Mendelson, Emmy Award winning executive producer of the classic Peanuts animated specials, and Charles Solomon, internationally respected animation historian and author of the new Chronicle book The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation, as they discuss the making of Peanuts animated specials. On Saturday, December 1, at 1:00 pm at the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Mendelson and Solomon will take you behind the scenes of nearly 50 years of Peanuts animation. Entry to the event is included in the price of Museum admission and is free for Museum members. Please arrive early as seating is first-come, first-served. 2301 Hardies Lane ● Santa Rosa, CA 95403 U.S.A. ● 707.579.4452 ● Fax 707.579.4436 www.SchulzMuseum.org © 2011 Charles M. Schulz Museum | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED | A non-profit 501(c)(3) organization PEANUTS © 2011 Peanuts Worldwide, LLC Lee Mendelson was the executive producer for all Peanuts animation from 1963 to 2010. A trio consisting of Mendelson, cartoonist Charles Schulz, and director/animator Bill Melendez produced 50 Peanuts network specials and four feature films. Mendelson’s network television productions have won 12 Emmys and 4 Peabody Awards. -

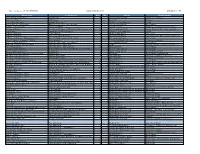

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Title Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style 1812 Overture (Finale) Tchaikovsky 15 6 Luigi's Listening Lab Listening, Classical 5 Browns, The Brad Shank 6 4 Spotlight Musician A la Puerta del Cielo Spanish Folk Song 7 3 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A la Rueda de San Miguel Mexican Folk Song, John Higgins 1 6 Corner of the World World Music A Night to Remember Cristi Cary Miller 7 2 Sound Stories Listening, Classroom Instruments A Pares y Nones Traditional Mexican Children's Singing Game, arr. 17 6 Let the Games Begin Game, Mexican Folk Song, Spanish A Qua Qua Jerusalem Children's Game 11 6 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A-Tisket A-Tasket Rollo Dilworth 16 6 Music of Our Roots Folk Songs A-Tisket, A-Tasket Folk Song, Tom Anderson 6 4 BoomWhack Attack Boomwhackers, Folk Songs, Classroom A-Tisket, A-Tasket / A Basketful of Fun Mary Donnelly, George L.O. Strid 11 1 Folk Song Partners Folk Songs Aaron Copland, Chapter 1, IWMA John Jacobson 8 1 I Write the Music in America Composer, Classical Ach, du Lieber Augustin Austrian Folk Song, John Higgins 7 2 It's a Musical World! World Music Add and Subtract, That's a Fact! John Jacobson, Janet Day 8 5 K24U Primary Grades, Cross-Curricular Adios Muchachos John Jacobson, John Higgins 13 1 Musical Planet World Music Aeyaya balano sakkad M.B. Srinivasan. Smt. Chandra B, John Higgins 1 2 Corner of the World World Music Africa: Music and More! Brad Shank 4 4 Music of Our World World Music, Article African Ancestors: Instruments from Latin Brad Shank 3 4 Spotlight World Music, Instruments Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 8 4 Listening Map Listening, Classical, Composer Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 1 4 Listening Map Listening, Composer Ah! Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser! French-Canadian Folk Song, John Jacobson, John 13 3 Musical Planet World Music Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around African-American Folk Song, arr. -

Stanford University, News and Publication Service, Audiovisual Recordings Creator: Stanford University

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dn43sv Online items available Guide to the Stanford News Service Audiovisual Recordings SC1125 Daniel Hartwig & Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2012 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stanford News SC1125 1 Service Audiovisual Recordings SC1125 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University, News and Publication Service, audiovisual recordings creator: Stanford University. News and Publications Service Identifier/Call Number: SC1125 Physical Description: 63 Linear Feetand 17.4 gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1936-2011 Information about Access The materials are open for research use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Cite As [identification of item], Stanford University, News and Publication Service, Audiovisual Recordings (SC1125). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

Charlie Brown Must Escort the Little Red-Haired Girl to the Homecoming Dance, Even Though He Has Trouble Kicking the Ball During the Football Game

Charlie Brown must escort the Little Red-Haired Girl to the Homecoming dance, even though he has trouble kicking the ball during the football game. Originally aired March 16, 1976 • 30 minutes While on guard duty, Snoopy falls in love with a poodle. Will they get married? Originally aired March 20, 1985 • 30 minutes Will Charlie Brown find love this Valentine’s Day? Originally aired February 14, 2002 • 30 minutes Will Charlie Brown receive any Valentine’s Day cards this year? Originally aired January 28, 1975 • 30 minutes Lee Mendelson, Jean Schulz, and Derrick Bang (author of 50 Years of Happiness) share their thoughts on the creation of Snoopy's lovable sidekick and best friend, Woodstock. This film is being shown in conjunction with the exhibition Peace, Love, and Woodstock. Originally aired October 20, 2009 • 15 minutes Produced and directed by Lee Mendelson, this documentary features a day in the life of Charles M. Schulz set between animated segments. Originally aired in 1963 • 30 minutes While on a field trip, Charlie Brown, Marcie, and Peppermint Patty mistake a supermarket for an art museum. Originally aired March 11, 1973 • 30 minutes Charles M. Schulz discusses the 50th anniversary of Peanuts. Originally aired October 19, 2003 • 30 minutes Charlie Brown agonizes over the Little Red-Haired Girl. Will he finally talk to her? Originally aired June 12, 1967 • 30 minutes Charlie Brown, Linus, Peppermint Patty, and Marcie travel to France as foreign exchange students. Also along are Snoopy and Woodstock. Charlie Brown is disturbed by a letter he receives from a mysterious French girl. -

December 2017 Snoopy and Woodstock but I Like Bossing People Around

Presents The Peanuts gang in A Charlie Brown Christmas! By: Carolyn Corsano Wong Photos: Michael Pittman Images The Peanuts Gang That’s right, the beloved Christmas special Normally, this show and You’re a Good Man relief, so I say a bunch of funny lines. And I can A Charlie Brown Christmas will be presented by Charlie Brown are cast with adult actors but Sara fall asleep (like Patty does) randomly during the STAGE RIGHT of Texas at the historic Crighton decided she wanted kids to portray kids (just as show!” – Patty, Gabby Rickwalt, 12 Theatre December 1-17. With story by Charles they were voiced in the TV special over 50 years “I’m playing my favorite character. I love M. Schultz and based on the television special by ago)! She has cast the show with an exceptional Christmas and so does Linus. I’m also Charlie Bill Melendez and Lee Mendelson it was adapted collection of talented kids: the cream of the crop Brown’s best friend.” – Linus, Keegan Pepper, 9 for the stage by Eric Schaeffer. STAGE RIGHT of young theatre artists in our area. We thought “I get to be sassy. I don’t want to sound mean leading lady, Sara Preisler, is the director and also it might be fun for you provided additional material. Sara is well known to get to know our cast to our audiences for her leading roles in some of so we asked them a our most popular musicals including Eliza in My few questions. These Fair Lady, Inga in Young Frankenstein and Kathy responses are unedit- Selden in Singin’ in the Rain. -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SONIC MOVIE MEMORIES: SOUND, CHILDHOOD, and AMERICAN CINEMA Paul James Cote, Doctor of Philosoph

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SONIC MOVIE MEMORIES: SOUND, CHILDHOOD, AND AMERICAN CINEMA Paul James Cote, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jonathan Auerbach, Department of English Literature Though the trend rarely receives attention, since the 1970s many American filmmakers have been taking sound and music tropes from children’s films, television shows, and other forms of media and incorporating those sounds into films intended for adult audiences. Initially, these references might seem like regressive attempts at targeting some nostalgic desire to relive childhood. However, this dissertation asserts that these children’s sounds are instead designed to reconnect audience members with the multi-faceted fantasies and coping mechanisms that once, through children’s media, helped these audience members manage life’s anxieties. Because sound is the sense that Western audiences most associate with emotion and memory, it offers audiences immediate connection with these barely conscious longings. The first chapter turns to children’s media itself and analyzes Disney’s 1950s forays into television. The chapter argues that by selectively repurposing the gentlest sonic devices from the studio’s films, television shows like Disneyland created the studio’s signature sentimental “Disney sound.” As a result, a generation of baby boomers like Steven Spielberg comes of age and longs to recreate that comforting sound world. The second chapter thus focuses on Spielberg, who incorporates Disney music in films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Rather than recreate Disney’s sound world, Spielberg uses this music as a springboard into a new realm I refer to as “sublime refuge” - an acoustic haven that combines overpowering sublimity and soothing comfort into one fantastical experience. -

'PEANUTS' Holiday Specials

Peanuts Worldwide Announces New Five Year Deal With ABC Network for the Classic 'PEANUTS' Holiday Specials August 16, 2010 NEW YORK, Aug 16, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Peanuts Worldwide, the newly formed joint venture between Iconix Brand Group (Nasdaq: ICON) and Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates today announced that it has signed a new five year deal with ABC Network for the popular PEANUTS animated holiday specials. The beloved Emmy Award winning specials, including the iconic "A Charlie Brown Christmas," "A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving" and "It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown," created by Charles M. Schulz and produced and animated by Lee Mendelson and Bill Melendez, began airing on ABC in December 2001. "The PEANUTS holiday TV specials are iconic and represent a family tradition of watching Charlie Brown and the gang kick off the holiday season," stated Neil Cole, CEO, Iconix Brand Group. Cole added, "This new deal with ABC demonstrates the continued relevance of the PEANUTS brand as it celebrates its 60th anniversary." This fall, the famed PEANUTS comic strip will celebrate its 60th anniversary. The first and most well known of the beloved animated holiday specials, "A Charlie Brown Christmas" first aired on television in 1965, marking this year as its 45th anniversary. Since moving to ABC nine years ago, the specials have continually delivered stellar ratings for the Network. Against competition including the season finale of NBC's "Biggest Loser," ABC's rebroadcast of the animated holiday classic "A Charlie Brown Christmas" finished a strong No. 2 in its half-hour in Adults 18-49 (3.7/11), beating slot-regulars CBS' "NCIS" replay by 37% (2.7/8) and Fox's original "So You Think You Can Dance" by 61% in Adults 18-49 (2.3/7). -

Kazu Kibuishi

April 2014 PEANUTS © 2011 Peanuts Worldwide LLC 10:15 There’s No Time for Love, Charlie Brown On a field trip Charlie Brown, Marcie, & Peppermint Patty mistake a supermarket for an art museum. Originally aired March 11, 1973 (30 minutes). 10:45 It’s Spring Training, Charlie Brown Charlie Brown’s team can get uniforms if they win their first baseball game of the season. Originally released January 1996 (30 minutes). 11:15 It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown Peppermint Patty tries to teach Marcie how to decorate eggs, Snoopy gets a birdhouse for Woodstock, and Linus convinces Sally that she doesn’t need to color eggs because the Easter Beagle will bring them. Originally aired April 9, 1974 (30 minutes). 1:00 Special Guest: Kazu Kibuishi Meet, watch, and talk to award-winning graphic novelist Kazu Kibuishi, creator of the series Amulet. Kibiushi is also known for his work editing the comic anthology Flight, and designing the book covers for the recent re-release of the complete Harry Potter book series. 3:15 A Boy Named Charlie Brown 1963 documentary featuring a day in the life of Charles Schulz (set between animated segments). Produced and directed by Lee Mendelson (30 minutes). 3:45 It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown Peppermint Patty tries to teach Marcie how to decorate eggs, Snoopy gets a birdhouse for Woodstock, and Linus convinces Sally that she doesn’t need to color eggs because the Easter Beagle will bring them. Originally aired April 9, 1974 (30 minutes). 4:15 The Charlie Rose Interview Originally aired May 9, 1997 (40 minutes). -

It's Your 20Th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown

It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown A web page about It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown. Written by Lee Mendelson (writer), "It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown" is an Animation/Family/Comedy film, released in the USA on May 14 of 1985 , starring Stacy Ferguson, Desirée Goyette, Gini Holtzman, Keri Houlihan, Chris Inglis and Marine Jahan. Released in the USA on May 14 of 1985, "It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown" is an Animation/Family/Comedy film written by Lee Mendelson (writer) . Stacy Ferguson is starring, alongside Desirée Goyette, Gini Holtzman, Keri Houlihan, Chris Inglis and Marine Jahan. When was "It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown" released it's your 20th television anniversary charlie brown, it's your 20th television anniversary charlie brown download It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown is an animated documentary television special based on characters from the Peanuts comic strip. Hosted by Peanuts creator Charles M Schulz, the television special originally aired on the CBS network in 1985. Voices. Brett Johnson: Charlie Brown voice. Bill Melendez: Snoopy voice. Happy Anniversary documentary. It's Arbor Day. It's Your First Kiss. Related Items. Search for "It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown" on Amazon.com. Share this Rating. Title: It's Your 20th Television Anniversary, Charlie Brown (TV Movie 1985). 7,4/10. Want to share IMDb's rating on your own site? A TV Special that summed up the 20th Television Anniversary for the Peanuts. Plot Summary | Add Synopsis.